This article, written by the well-known American reporter stationed in Paris over many years, W. F. Bradley, gives the background of the very first European application of Michelin pneumatic tyres. The 1895 Paris-Bordeaux contest wasn’t a success for them at all. But the disappointment on that very first experience with pneumatic tyres during a contest or, call it as you like, a race, was the start for the ever so succesfull years of Michelin tyres.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Motor Age, Vol. XXXIX (39), No.23, June 9, 1921

Where the Pneumatic Tire got its Start

Back in 1895 the Michelin Brothers Demonstrated the Ability of Pneumatics to Stand Up in a Race from Paris to Bordeaux

By W. F. Bradley European Correspondent of Motor Age.

Introduction

IN view of the fact that Tommy Milton changed but two tires in the 500-mile Indianapolis race this year, it is interesting to go back 27 years to the time of the Paris to Bordeaux race and see how the pneumatic tires – the first ones ever put on a car – fared. The early automobile engineers were afraid of the pneumatic tire because of its fragility. This is not surprising, but it is surprising, in view of present day performance of the pneumatic tires on the race track, to think the early engineers were afraid of the pneumatic tire, thinking it had not the ability to reduce friction.

SELLING automobile tires twenty-seven years ago was a much more difficult task than the same operation in 1921. Away back in 1894 Andre and Edouard Michelin believed they had an air-filled rubber bandage which ought to be applied to the wheels of automobiles, but they were totally unsuccessful in converting engineers and car manufacturers of that period to their way of thinking.

The Michelin brothers had hopes that the Paris to Bordeaux and return automobile race, which was decided on near the end of 1894 and fixed for June of the following year, would be an excellent occasion on which to prove to the world that automobiles could be run with every advantage on pneumatic tires.

Unfortunately for them, every manufacturer, including such firms as Peugeot, Panhard-Levassor, De Dion Bouton, Decauville, Gladiator, and others having ceased to be known in the automotive industry, refused to be interested in a tire filled with air. It was on this account that the Michelin brothers decided to build their own cars, fit them with pneumatic tires, and run them in the race to Bordeaux and back.

This, undoubtedly, constituted the first use of pneumatic tires on a self-propelled vehicle, although of course not the first time a tire was used on the road, for at that period the pneumatic was fairly extensively employed on bicycles, and had also been use in France and elsewhere on a few horse-drawn cabs.

Michelin’s appearance as an automobile manufacturer was not particularly brilliant, and the first use of a pneumatic tire in an automobile road race was not an untarnished success. In order to make a good showing in the road race, it was decided to build three cars, which were known respectively as The Swallow, The Spider, and The Lightning.

The first was a Benz chassis with belt transmission and pneumatic pulleys to give greater adherence. The car was sent from Clermont-Ferrand in the center of France, where the Michelin fac- tory is located, in order to reach Paris for the start of the race, but it died on the way with a cracked cylinder.

The Spider was not much longer lived. This car had a 6-hp. marine engine bought in Canstatt, Germany, and because the de- signer had overlooked the pump, the engine had to be set considerably out of center, to the great disadvantage of the steering. This defect manifested itself on the road to Paris, when the car charged a tree, caught fire, and became a complete wreck. Only „Lightning“ remained.

The product was a Peugeot 2½ hp. chassis with a 4 hp. Daimler marine engine which, like its unfortunate companions, had to be set out of center because of the neglect to provide a place for the pump. The car weighed 3086 lbs., it had big diameter wire wheels with pneumatic tires of 2½ in. section; it was so unreliable that it had to carry at the rear a big locker, of 1½ in. pine, divided into numbered drawers, and it refused to run in a straight line.

While training drivers for the race, the car was wrecked twice. On the second occasion, only three weeks before the contest, the car turned over in the ditch and took fire, and after it had been rebuilt the trained drivers refused to have anything more to do with it; as a consequence the Michelin brothers themselves decided to start in the race as driver and mechanic.

It was not a brilliant victory for the pneumatic, nor did the car show to great advantage against the numerous competitors, comprising Serpollet steamers, Peugeots, Panhard-Levassors, de Dion Bouton steamers and some electrics, all equipped with solid rubber tires. Paris only constituted the rallying point for the competitors, the start of the race being given at Versailles, about twelve miles away.

Michelin was not on time at the meeting point, at the Arc de Triomphe, Paris, for the wick carburetor refused to carbu rate, and he was late in getting his official start at Versailles, but that did not prevent his getting away among the competitors for the 869 mile trip, the only one among forty to run on pneumatics.

The 2½ in. tires, with their load of more than 3000 lbs. punctured on an average every ninety miles, and as each tire was held on its rim by twenty safety bolts, repair was a slow matter, and the average was not high notwithstanding wild rushes downhill at 35 miles an hour.

The world’s first pneumatic automobile reached Bordeaux and returned to Paris, and although it did not figure among the winners, for it exceeded the time limit of 100 hours stipulated under the rules, its tires excited interest and favorable comment from Levassor, the builder of the Panhard-Levassor car.

While it is not surprising that the early automobile engineers should have been afraid of the first pneumatic tires because of their fragility, it does seem rather curious, at the present day, that they should have been skeptical regarding the ability of the tire to reduce friction.

Because of this, public demonstrations were made in 1896 on a de Dion Bouton six-cylinder steamer weighing, in running order, 5470 lbs. This vehicle was run over a selected road first with solid and then with pneumatic tires, with the result that an economy of 28.2 per cent in the weight of coke and water was obtained by pneumatics, with an increase in the average speed of three miles an hour.

Michelin was convinced that the pneumatic was the tire of the future, and he refused to build solids which were then being used by everybody. But although he had faith in the pneumatic, he was not satisfied with the methods of construction, and from June, 1895, to February, 1896, he built tires but refused to sell them. During that time, he kept several cars on the road, in the hands of his commercial travelers, and was satisfied with the publicity obtained and the experience acquired.

In May, 1896, a Michelin car with pneumatic tires won second prize in the Bordeaux to Agen race, over a distance of 85 miles. The first really important public performance of the pneumatic tire was in the 1056 mile race from Paris to Marseilles and return. This event stands forth as a classic, for it was the first occasion on which electric ignition was used in a public competition, and also the first time automobile manufacturers preferred pneumatics to solids.

The first three places were secured by Panhard-Levassor cars on solid rubber tires, but Ernest Archdeacon got fourth place on a pneumatic-shod Delahaye and Bollee and de Dion Bouton cars finished the long trip on pneumatics. It was during this race that Levassor met with an accident which did not appear serious at the time, but from which he died in less than a year.

The first automobile race to be won on pneumatic tires was the Marseilles to Nice of 1897, in which Michelin drove a steamer weighing 6335 lbs. and covered a distance of 125 miles at an average of 38 miles an hour. This speed was maintained with tires of only 2½ in. section.

The race was not won easily. In order to increase his chances, coke fires had been prepared by Michelin at various places along the road, and from these live coke was taken and put into the automobile. After running 50 miles a tire burst, and a mile further another casing ended its existence. Having started last. Michelin had got into second place, after passing forty competitors, but the tire trouble threw him back and he was among the last to reach St. Raphael, the end of the first stage.

It was realized that the tires, a new series fitted just before the race, were of defective construction, and in consequence a telegram was sent to the factory at Clermont-Ferrand, for a special messenger to be sent to St. Raphael during the night with a set of old and tested tires. These were fitted and the second and final stage of the race began. For a long time Chasseloup-Laubat held the lead and was the first to get into Cannes. Here Michelin had to stop for water and to grease up, but the work was done in half a minute, and a short time afterwards Chasseloup-Laubat was overtaken with heating trouble and Michelin ran into Nice earlier than expected, winner of the first automobile race on pneumatic tires.

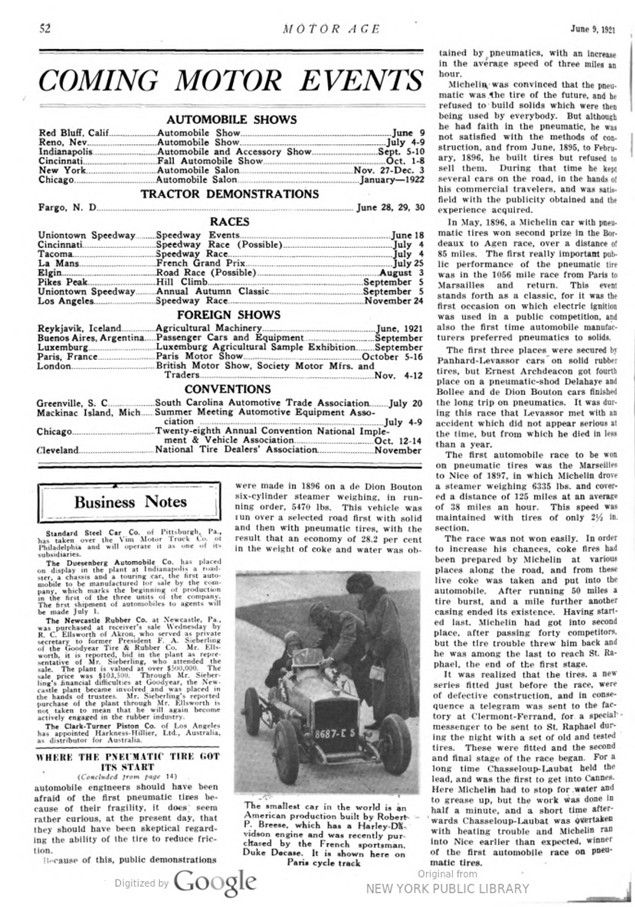

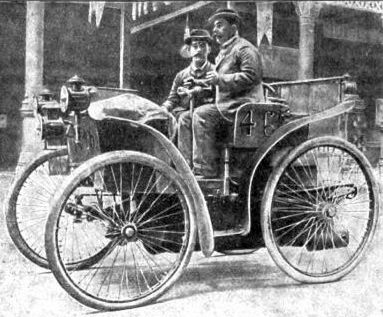

Photo caption.

The first car in the world to be run on pneumatic tires. This car was built by the Michelin brothers and equipped with a Daimler engine. It ran in the Paris to Bordeaux race in 1895