The French magazine La Vie au Grand Air published August 1911 this article on the Indianapolis race, about the track itself and highlighted the incident at the end of the 500-mile race.

Texte et jpegs avec l’autorisation du Bibliothèque national francais gallica.bnf fr et compilé par motorracinghistory.com

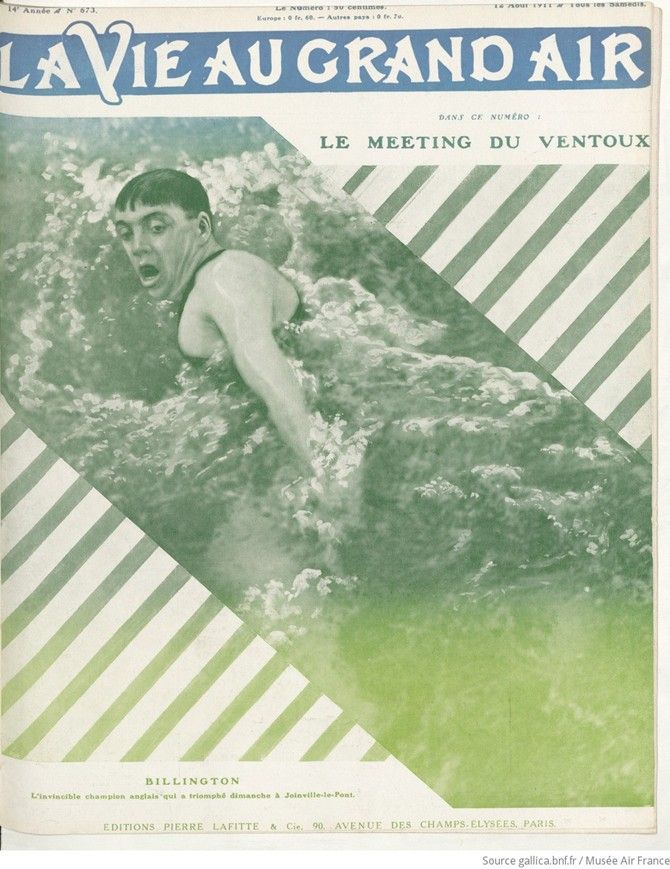

La Vie au Grand Air, 14e Année, No. 673, 12 Aout 1911

UNE COURSE MOUVEMENTÉE

Les courses sur piste qui se disputent en Amérique ne vont pas sans de nombreux accidents. Celui qui se produisit au dernier meeting d’Indianapolis est bien caractéristique.

TANDIS que le sport automobile subit en Europe une éclipse que nous aimons à croire passagère, sa vogue, au contraire, en Amérique, ne fait que croître. Mais, comme il n’y a pas, pour ainsi dire, de routes, de l’autre côté de l’Atlantique, c’est sur piste que se déroulent les luttes entre les monstres de vitesse que crée l’imaginative industrie des Américains.

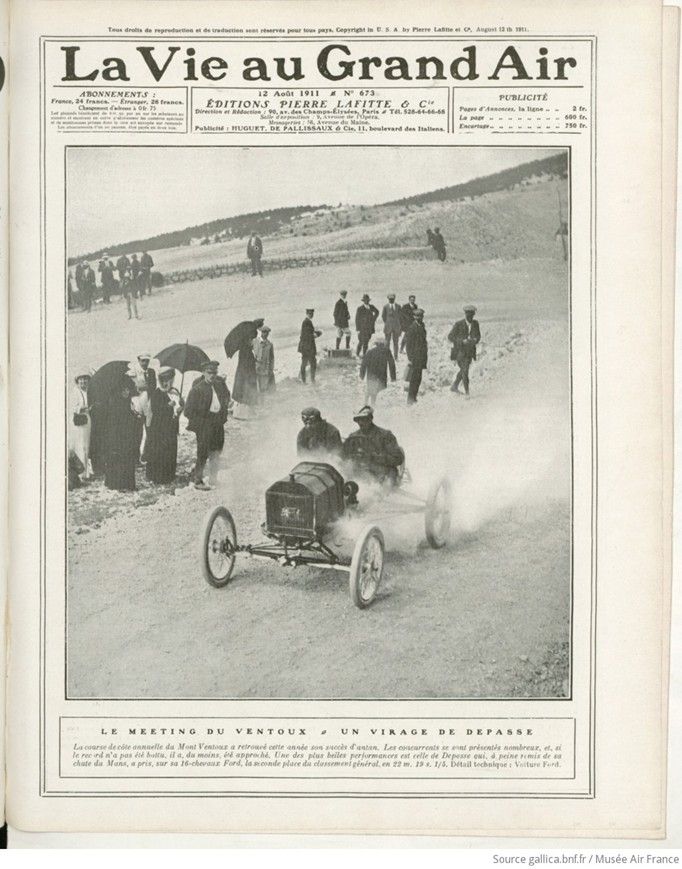

Nous avons déjà eu l’occasion (1) de parler du mirifique programme annoncé, pour la saison, par l’Indianapolis Motor Speedway, sur laquelle se disputent, naturellement, « the greatest races in the world ». On sait que c’est la formule chère aux Yankees. Cette piste d’Indianapolis couvre une superficie de 135 hectares, et elle n’est qu’à 4 milles du centre de la ville d’Indianapolis, la capitale de l’Indiana. Il est certain qu’en France, pareil espace libre aux portes d’une grande ville supposerait un capital énorme. En fait, l’autodrome en question a coûté plus de 700.000 dollars (3.500.000 Francs). (1) Voir le no 649.

La piste mesure 2 milles et demi, soit un peu plus de 4 kilomètres. Elle est entièrement en briques vitrifiées et 3.500.000 briques ont été employées pour cet usage. Un mur en ciment de 3 pieds de haut entoure les virages. Le centre de la piste constitue un superbe aérodrome et un parc de ballons permettant le gonflement et le départ simultané de 10 à 15 sphériques. Quarante et une constructions diverses : garages d’autos et d’aéroplanes, cafés, restaurants, salles de réunions, etc., trouvent place à l’intérieur du champ. Les tribunes peuvent contenir 40.000 spectateurs assis et 20.000 autres debout peuvent être admis dans les différentes enceintes. Il y a place également pour 10.000 automobiles. Un pont pour les piétons et un autre pour les voitures permettent de se rendre de l’extérieur à l’intérieur de la piste.

A noter que le prix des places est très bon marché, puisqu’il n’est que d’un dollar, — 5 fr. et 7 fr. 50 pour les places réservées.

Tel est, en quelques mots, l’aspect d’un de ces autodromes comme il en existe une dizaine aux Etats-Unis. Les courses sur ces immenses pistes sont, on le conçoit, très mouvementées. Le danger qu’elles présentent en augmente l’intérêt et si on en juge par le succès que remportent chez nous les courses de motocyclettes ou les courses derrière motos, on peut croire que le spectacle de voitures, lancées à 120 ou 130 kilomètres à l’heure et luttant roue à roue à pareille allure dans les virages, ne manquerait pas d’avoir des spectateurs assidus. Songez que-dans une épreuve, le Wheeler-Schebler Trophy, vingt-deux concurrents, rangés sur trois lignes, prirent le départ en même temps, et s’élancèrent dans une fumée d’huile, au milieu des pétarades des moteurs, au signal du starter. Dans la finale du handicap couru le même jour, 17 voitures terminèrent en moins de 200 mètres.

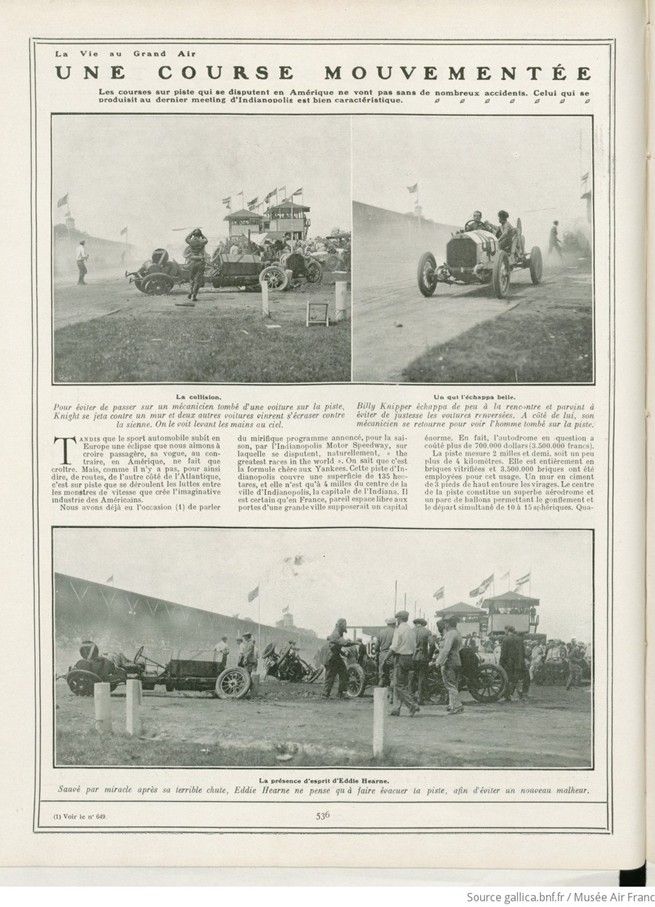

De telles courses, on le comprend facilement, ne vont pas sans quelques accidents. Les rencontres sont nombreuses et celle que nos photographies reproduisent aujourd’hui peut compter pour une des plus curieuses, encore qu’elle ne fit qu’une victime. Mais c’est un vrai miracle qu’il n’y eût pas cinq ou six morts.

Pour éviter de passer sur un mécanicien qui était tombé de voiture devant lui, en face des tribunes, un des coureurs, Harry Knight fit une brusque embardée et vint s’écraser sur le mur qui bordait la piste en cet endroit. Deux autres voitures qui le suivaient, celles d’Eddie Hearne et d’Herb Lytle, vinrent se jeter sur lui.

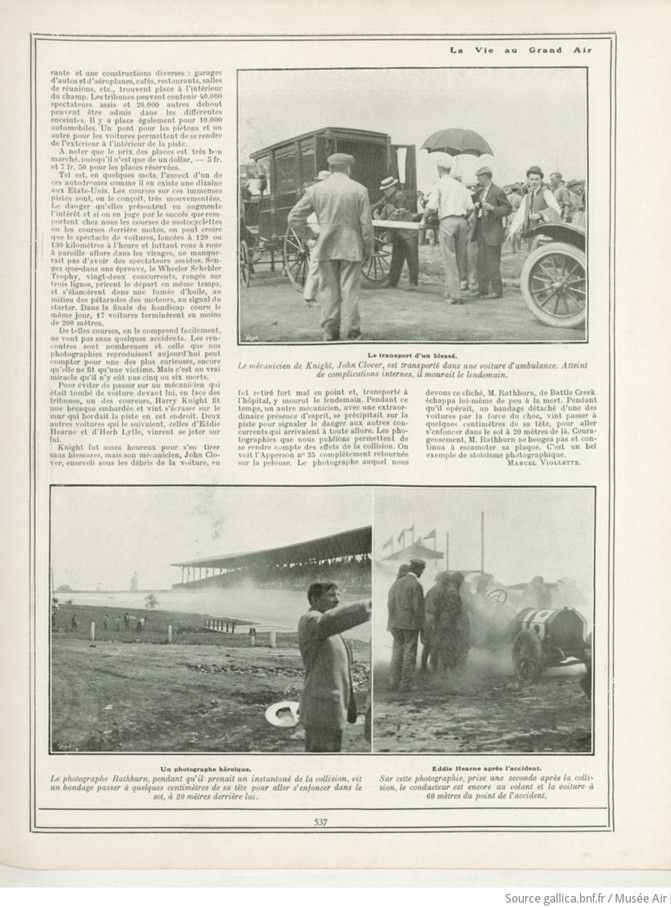

Knight fut assez heureux pour s’en tirer sans blessures, mais son mécanicien, John Clover, enseveli sous les débris de la voiture, en fut retiré fort mal en point et, transporté à l’hôpital, y mourut le lendemain. Pendant ce temps, un autre mécanicien, avec une extraordinaire présence d’esprit, se précipitait sur la piste pour signaler le danger aux autres concurrents qui arrivaient à toute allure. Les photographies que nous publions permettent de se rendre compte des effets de la collision. On voit l’Apperson n° 35 complètement retournée sur la pelouse. Le photographe auquel nous devons ce cliché, M. Rathburn, de Battle Creek échappa lui-même de peu à la mort. Pendant qu’il opérait, un bandage détaché d’une des voitures par la force du choc, vint passer à quelques centimètres de sa tête, pour aller s’enfoncer dans le sol à 20 mètres de là. Courageusement, M. Rathburn ne bougea pas et continua à escamoter sa plaque. C’est un bel exemple de stoïcisme photographique.

MARCEL VIOLLETTE.

Photo descriptions.

La collision.

Pour éviter de passer sur un mécanicien tombé d’une voiture sur la piste, Knight se jeta contre un mur et deux autres voitures vinrent s’écraser contre la sienne. On le voit levant les mains au ciel.

Un qui l’échappa belle.

Billy Knipper échappa de peu à la rencontre et parvint à éviter de justesse les voitures renversées. A côté de lui, son mécanicien se retourne pour voir l’homme tombé sur la piste.

La présence d’esprit d’Eddie Hearne.

Sauvé par miracle après sa terrible chute, Eddie Hearne ne pense qu’à faire évacuer la piste, afin d’éviter un nouveau malheur.

Le transport d’un blessé.

Le mécanicien de Knight, John Clover, est transporté dans une voiture d’ambulance. Atteint de complications internes, il mourait le lendemain.

Un photographe héroïque.

Le photographe Rathburn, pendant qu’il prenait un instantané de la collision, vit un bandage passer à quelques centimètres de sa tête pour aller s’enfoncer dans le sol, à 20 mètres derrière lui.

Eddie Hearne après l’accident.

Sur cette photographie, prise une seconde après la collision, le conducteur est encore au volant et la voiture à 60 mètres du point de l’accident.

Translated by DeepL.com

Text and jpegs by courtesy of the Bibliothèque national francais gallica.bnf fr and compiled by motorracinghistory.com

AN EVENTFUL RACE

Track racing in America is not without numerous accidents. The one that occurred at the last meeting in Indianapolis is very characteristic.

WHILE motor sport in Europe experiences a downfall, we like to believe it will pass; on the other hand, its popularity in America is on the rise. But as there are no roads, so to speak, on the other side of the Atlantic, it is on the track that the battles between the speed monsters created by the imaginative American industry take place.

We have already had the possibility (1) to talk about the fabulous programme for the season announced by the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, where, naturally, ‚the greatest races in the world‘ are contested. As we all know, this is the formulation the Yankees cherish. The Indianapolis track covers an area of 135 hectares and is only 4 miles from the centre of Indianapolis, the capital of Indiana. Certainly, in France, such an open space on the outskirts of a major city would assume enormous capital. In fact, the racetrack in question cost over 700,000 dollars (3,500,000 francs). (1) See no. 649.

The track measures 2-and-a-half miles, or just over 4 kilometres. It is made entirely of vitrified brick and 3,500,000 bricks were used for this purpose. A cement wall of 3 feet high surrounds the bends. The centre of the runway is a superb aerodrome and a balloon park where 10 to 15 spherical balloons can be inflated and launched simultaneously. Forty-one different buildings – car and aircraft garages, cafés, restaurants, meeting rooms, etc. – are located inside the field. The grandstands can accommodate 40,000 spectators seated and a further 20,000 standing in the various surroundings. There is also room for 10,000 cars. A bridge for pedestrians and another for cars allows access from outside to inside the track.

Note that tickets for seats are very cheap, costing just one dollar – 5 francs and 7.50 francs for reserved seats.

That, in some words, is what one of these racetracks, of which there are a dozen in the United States, looks like. Races on these immense tracks are, understandably, very hectic. The danger they present makes them even more interesting and judging by the success of motorbike and motorbike races in the United States, the spectacle of cars hurtling along at 120 or 130 kilometres an hour, fighting wheel to wheel at the same speed in the bends, is bound to attract a large number of spectators. Consider that in one event, the Wheeler Schebler Trophy, twenty-two competitors, lined up in three rows, started at the same time, and took off in a smoke of oil, amid the backfire of engines, at the starter’s signal. In the handicap final run on the same day, 17 cars finished within 200 metres.

One understands easily that races like this are not without some accidents. There are many of these encounters, and the one reproduced in today’s photographs is one of the most curious, although it only claimed one victim. But it’s a real miracle that it were not five or six deaths.

To avoid driving over a mechanic who had fallen out of a car in front of him, in front of the grandstands, one of the drivers, Harry Knight, swerved abruptly and crashed into the wall that lined the track on this point. Two other cars that followed him, those of Eddie Hearne and Herb Lytle, crashed into him.

Knight was lucky enough to escape without injury, but his mechanic, John Clover, buried under the wreckage of the car, was pulled out hard and taken to hospital; he died the next day. Meanwhile, another mechanic, with extraordinary presence of mind, rushed to the track to warn the other competitors who were arriving at full speed. The photographs we are publishing give an idea of the effects of the collision. Apperson No. 35 can be seen completely overturned on the grass. The photographer to whom we owe this photograph, Mr Rathburn of Battle Creek, himself narrowly escaped death. While he was photographing, a bandage from one of the cars loosened by the force of the impact, passed a few centimetres from his head and hit the ground 20 metres away. Courageously, Mr Rathburn did not move and continued to retract his plate. It’s a fine example of photographic stoicism.

Photo captions.

The collision.

To avoid running over a mechanic who had fallen from a car onto the track, Knight swerved into a wall and two other cars crashed into his. He can be seen raising his hands to the sky.

A close call.

Billy Knipper narrowly escaped the collision and managed to avoid the overturned cars. Next to him, his mechanic turns to look at the man who has fallen onto the track.

Eddie Hearne’s quick thinking.

Miraculously saved after his terrible fall, Eddie Hearne’s only thought is to clear the track to prevent another accident.

Transporting an injured person.

Knight’s mechanic, John Clover, is taken away in an ambulance. Suffering from internal injuries, he died the next day.

A heroic photographer.

Photographer Rathburn, while taking a snapshot of the collision, saw a bandage fly past his head and sink into the ground 20 meters behind him.

Eddie Hearne after the accident.

In this photograph, taken a second after the collision, the driver is still at the wheel and the car is 60 meters from the point of the accident.