Text and pictures with courtesy of hathitrust hathtrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory

The Motor World, Vol. IX, No. 3, October 13, 1904; pages 97 – 104

The Story of How George Heath, an American, won the Vanderbilt Cup for France.

„Five killed; seven injured.“ This was the „score sheet,“ or „extra,“ issued and actually sold on the course during the contest by one of the „yellows“ that had worked itself into a saffron frenzy and dealt in „Race with Death“ scare heads previous to the race for the Vanderbilt Cup.

The „news“ flabbergasted even those familiar with the workings of yellow imaginations. It seemed incomprehensible. But after the race had been run a basis for the „news“ was discovered. The holes of the tripe-like cooler of the winner’s car were found to be filled with dozens of dead bodies, many of them held tightly to the metal breastplate by their own congealed gore, others crushed beyond hope of recognition. It was a sight to move a jellow journal to red head lines.

The slaughter of the innocents – of the poor, inoffensive, in offending Long Island insects – was awful. They evidently had dared what the shrieking yellows themselves had failed to do-to stop the race, and alas! they had been ruthlessly hurled into the buggish eternity without time even to hum a farewell prayer. It is assumed that a yellow reporter had found somewhere on the course the corpses of five dear little bugs and the still kicking bodies of seven injured ones, and „dreamed“ one of those „dreams“ of which yellow „extras“ are so often made.

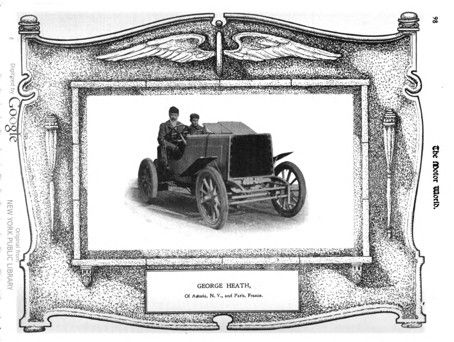

He is a very ignorant or uninformed or disinterested person who is not aware that George Heath, an American by birth, a Parisian by virtue of residence, and an Englishman in manner and appearance, was the bug-slaughtering individual who won the inaugural race for the W. K. Vanderbilt, Jr. Cup on Saturday last, October 8, and that he occupied 5 hrs., 26 mins. and 45 secs. in covering the 284.40 miles of Long Island roads.

Similarly, the world of intelligence must know as well that Albert Clement, of France, a Frenchman, finished second, and promptly lodged a protest, which was almost as promptly disallowed.

Only these two finished — no more. That an American in an American car did not finish third was due to no fault of his own or of his car, but to the antics of his countrymen, and, in great part, automobilists. Like a lot of thoughtless children, they swarmed all over the road, and made travel so dangerous that to protect them from their own folly the officials of the race ordered it stopped. The order halted the American, Herbert H. Lyttle. When his not then esteemed fellow citizens had scattered to the four winds and made progress safe, Lyttle, for personal gratification, completed the final round of the course, and though he was neither officially checked nor officially timed, and does not so figure in the official table, he is still able to place his hand on his chest and exclaim: „I finished, any how!“ The gratification was worthwhile, for in a 24-horsepower stock car Lyttle had given a wonderfully steady and consistent performance throughout.

The race was marred by one accident. If it is possible to extract happiness from such a lamentable occurrence, it lies in the fact that the victims were not spectators, but competitors in the race itself. Chauffeur Carl Menzel is dead, and his wealthy employer, George Arents, who drove the ill-fated car, is, after several days of unconsciousness, slowly returning to health. The best evidence makes it appear that they suffered partly because of their own excitement and zealousness. He had ridden at an awful pace for many miles with one wheel minus a tire. They also had replaced a tire, and did not secure it properly. When it burst – there is some testimony that one of its mates also burst at the same moment-they apparently performed the too common act of quickly and violently applying the brakes. A wheel collapsed; the car upset. The life was crushed out of one man; the other was quickly conveyed to a hospital with his life trembling in the balance.

——-

While it is given to novelists to conceal to the end the keys to their stories, it is a part of newspaper ethics and practice that the text of an important news happening shall be summarized in the first few sentences. This chiefly that the man who has no liking for details-for the lights and shadows that lend human interest to an event-may gulp the bare facts and throw his newspaper to the hired man or leave it in the streetcar for the information or irritation of the conductor or street cleaning department. It is a duty which every well-regulated reporter must perform, whether or not. The Motor World reporter has performed that duty – and stretched his license in doing so. The real story-the full narrative of the race-is, if not strictly of absorbing interest, rich in color and incident.

MR. „WIFFLE“ AND THE INJUNCTION.

The day before the race, and the night before it, Garden City, in the centre of the triangle and off the course itself, was the vortex. It was there that the cars were weighed, and it was during the weighing that Heath, the ultimate winner, and Clement, the second man, resolutely declared that before they would submit to having their cars out of their possession overnight, they would not start in the race. The unknown and unexpected rule requiring it was quickly abrogated, and that ugly wrinkle smoothed out. It was late the night before (Thursday) that an even greater, if not wholly unanticipated hitch presented itself. A becoming gentleman appeared at the Garden City Hotel, where President Whipple, of the American Automobile Association, and all other officials and practically everyone else who is anybody was stopping.

The becoming gentleman inquired for „Mr. Wiffle.“ It was suspected that Mr. Whipple was the man wanted. He was found and jokingly introduced to the b. g. as „Mr. Wiffle.“ He promptly thrust a legal looking document into „Wiffle’s“ hand. It proved to be an order to appear in court the following day and show cause why an injunction restraining the race should not be granted. The army of newspaper reporters that was hovering near promptly rushed for the tele- graph office; it was worked overtime.

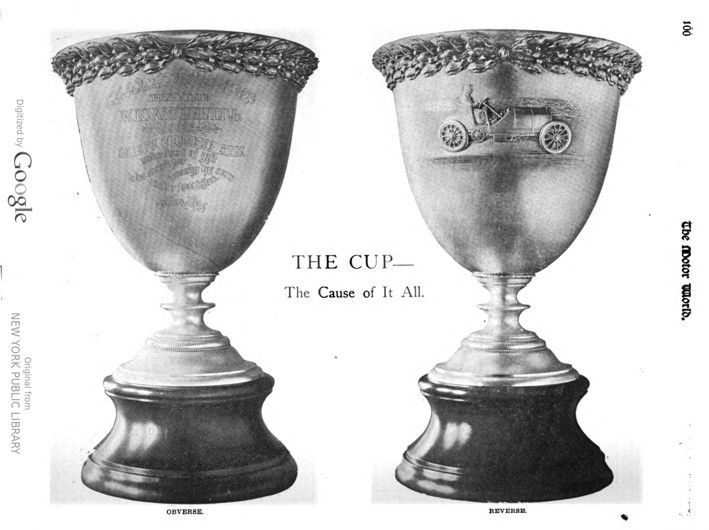

Of course, Mr. Whipple obeyed the order. The gathering in court was a notable once and included the donor of the cup which was the cause of it all. The proceedings were not protracted. The court heard the counsel of both sides and then promptly denied the injunction. He told the plaintiffs, the so-called People’s Protective Association, that the law plainly authorized the authorities to grant the use of the roads for speed purposes and suggested that if relief was desired the legislature was the place to obtain it.

The decision of the court caused no elation or demonstration. On the part of those interested in the race it was accepted as a matter of course.

RESEMBLED A BRIDGE CRUSH.

Friday night the palatial hotel at Garden City was a sight to see. The crowd was so great that to make progress it was necessary for one to elbow his way. It suggested a Brooklyn Bridge crush during the rush hours. Millionaires, gentlemen of leisure, tradesmen and chauffeurs mingled in delightful profusion. Throughout the night motor cars and trains added to the throng. Every bed had been engaged days or weeks before, and every room contained many occupants. The hotel was compelled to suspend rules and men were permitted to sleep-if they could-in chairs. There is even a story that the barber’s chair was leased for the night. Chauffeurs slept in cars that were parked in long lines, and, in many places two deep, under the trees of the hotel. The Cleveland Automobile Club „saved the lives“ of a number of wayfarers. A party of the Clevelanders came on in a special coach that was run onto a side track. The men slept in the car, and as there were several berths to spare, they „took in“ and provided beds and rest for several heavy-eyed rovers unable to find even a chair to sit on.

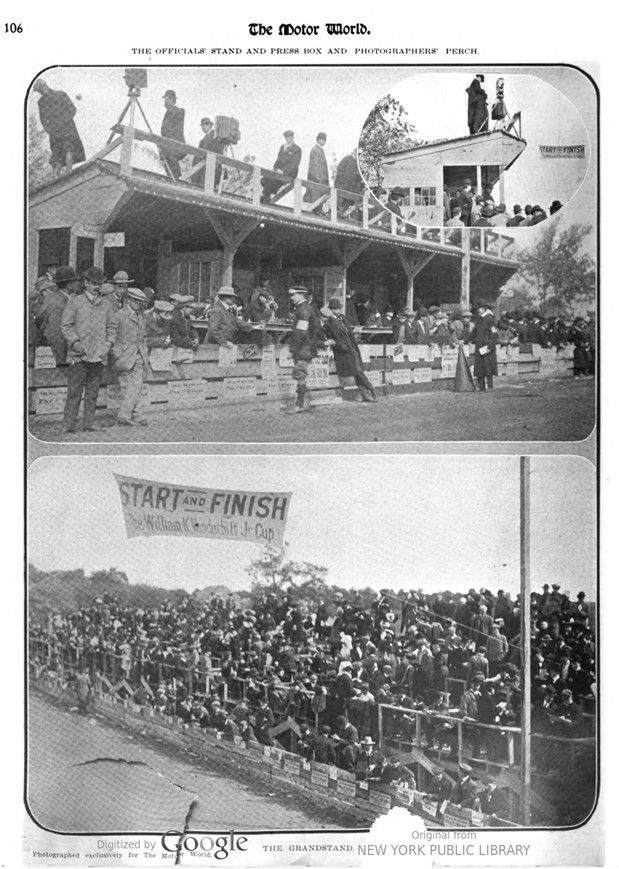

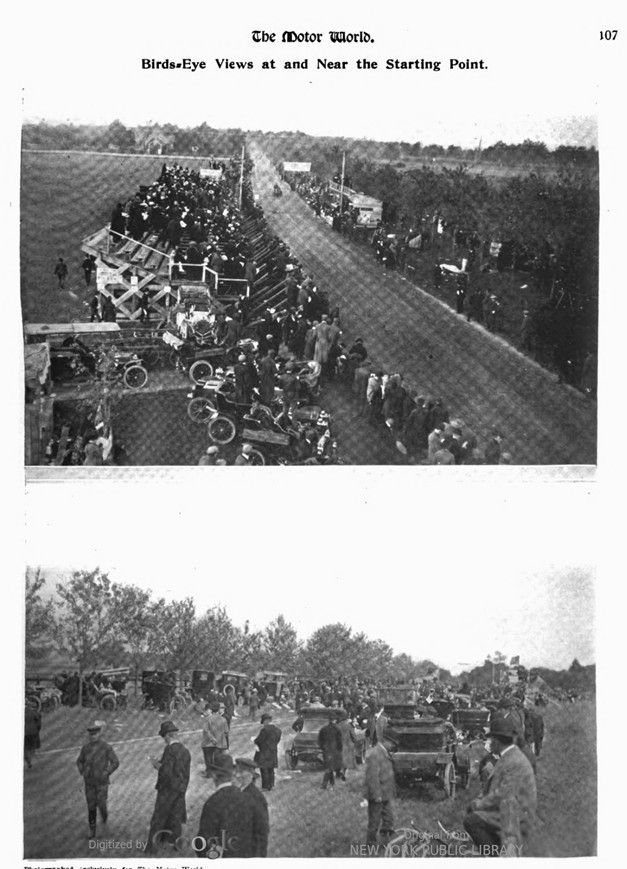

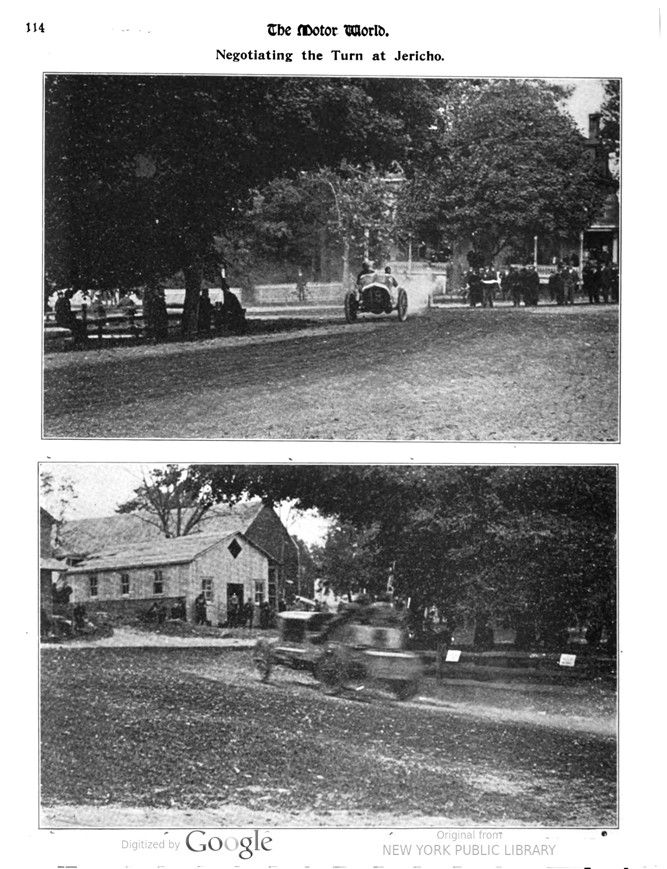

It was cold and raw and not yet daylight when the whole country was astir with automobiles and horse-drawn vehicles of every age, condition and description. The roads were alive with them. Nearly all were headed for the starting point at Westbury, and in that darkest hour, just before dawn, and in the gray of the dawn the great headlights of the motor cars seen in the far distance appeared as if hung in space, suggesting nothing so much as twin moons or suns floating close to earth. Most of the vehicles stopped at the grandstand at the starting point, near which a large American flag fluttered from a tall staff – the only semblance of decoration or embellishment in evidence. Many of the occupants of the vehicles repaired to the stand; others remained in their cars, which parked in long lines on either side of the road. Not all who came to see, however, so disposed themselves; indeed, it seemed as if the greater number preferred to remain on the road itself. Already a number of the giant racing cars were on the spot „vibrating with confined emotion.“ Their proximity had no effect on the crowd; if anything, each new arrival seemed to draw more spectators from somewhere. The road was black with them, and the efforts of the special constables, blessed with a little brief authority, and of the race officials, were of small avail. The people opened out and formed a human lane only when the first car was making ready to start. And at that very moment a party of apparent affluence in a White steam car and which had apparently imbibed not wisely but all night, appeared on the scene. They were stopped almost on the starting line. Protests and pleadings were of no avail. They refused to budge and made as if to charge the crowd. Once it seemed as if they would run down the dapper referee, none other than W. K. Vanderbilt, jr., himself. It was then that ready hands were laid on the car, and despite the efforts of the occupants, it was rolled aside.

THE START-„GO!“

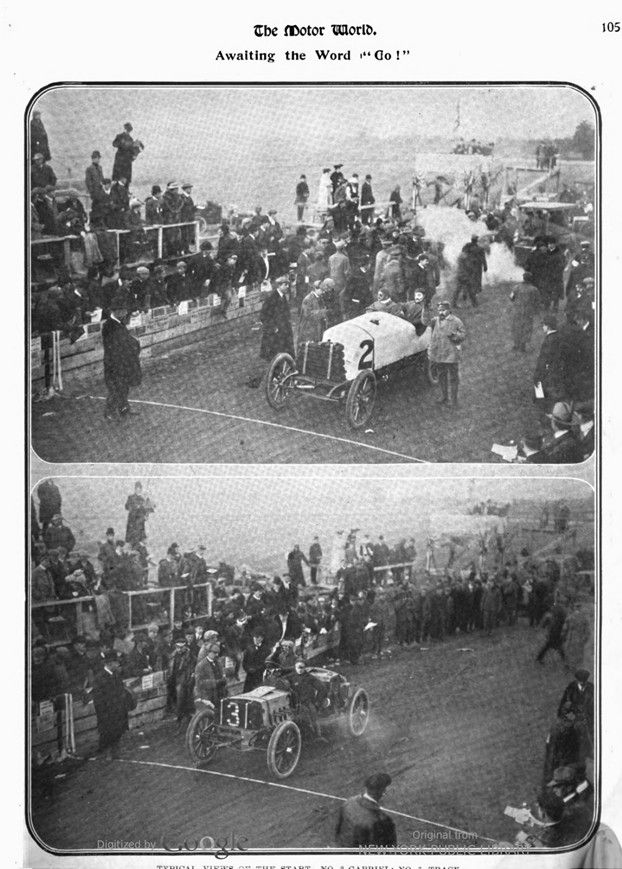

The first car, S. B. Stevens’s Mercedes, driven by Campbell, throbbed and snorted like a demon tugging at its bonds. At 6 o’clock sharp the word „Go“ and not a pistol shot slipped the leash, and it was off. A few scattered cheers greeted this, the start, of the first really great automobile race ever run in America.

Gabriel, in his long white car, got away slowly, two minutes later. He was much fancied, possibly the most fancied, certainly by the country folk, and was perhaps more warmly greeted than any of the others, which is not, however, saying a great deal. The chill of the morning did not contribute to enthusiasm. Unassuming Joseph Tracy, in the American Royal, which angrily belched smoke through its four exhaust pipes protruding through the side of the hood like miniature cannon in the turret of a midget warship, received the word at 6:04. The sixth car, No. 6, the 25 horsepower Pope- Toledo, contained what undoubtedly were two human beings, but they did not look it. They were garbed entirely in black leather; even their faces were completely masked in black. They were an uncanny pair, sufficient to frighten any child out of a year’s growth. They looked like devils or deep-sea divers, and not even his mother would have recognized the figure at the wheel as H. H. Lyttle, who, after working all night to repair a slight break, held up the prestige of American manufacture and skill in a style that has since been the remark of his countrymen. The figures by laps will serve to show how nearly the running of his car approximated clockwork. That other and sometimes or one time American, George Heath, who sought to secure the laurels for France, was in dress the antithesis of Lyttle. He was attired as if for a pleasure spin, in a golf or cycling suit, cloth cap and ordinary overcoat. He wore also a standing collar and white puff tie, and looked handsome, healthy and wholesome.

The start, however, was really devoid of incident. Each moment the crowd increased, and the hedge of humanity that bordered each edge of the oiled strip lengthened and deepened, and only when Frank Croker made ready to start and his low- hung car drew up to the line and „backfired‘ in vicious volleys and rumbled and thundered like a battleship did the crowd evince the slightest disposition to increase the elbow room.

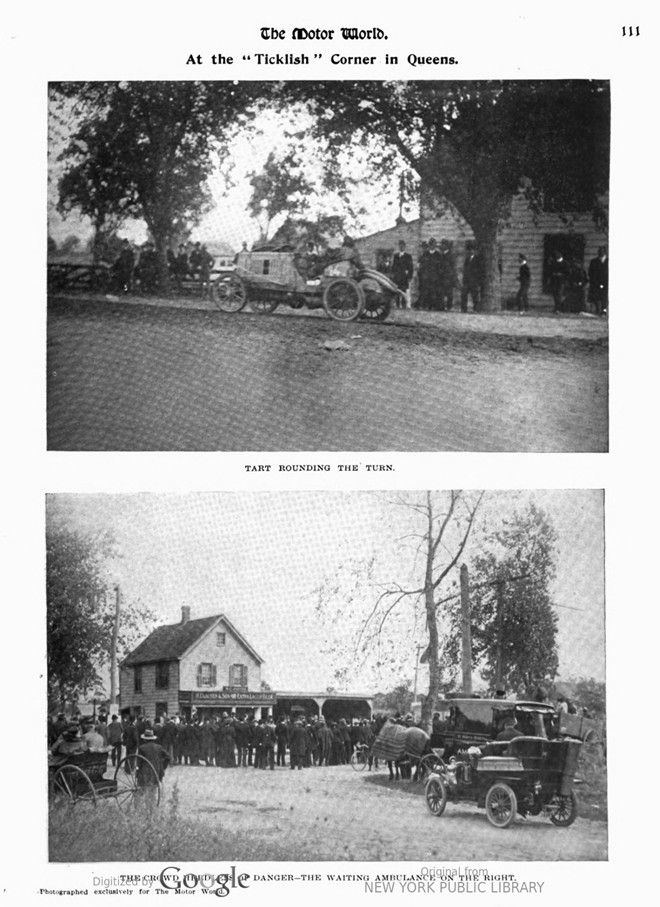

„GOD WAS GOOD TO THEM.“

„God certainly was good to them,“ was the remark at the close of the day of one man who beheld the scenes at the starting points and witnessed the heedless crowds at the dangerous turns. It is not short of miraculous that none was injured. This feature of the race was in striking contrast to the discipline and clear courses that marked the Bennett cup races in Ireland and Germany. On those occasions, a spectator on the road was the exception, here it was the rule. There were no soldiers and not even a blue-coated policeman to command respect. The country constables who served or were sup- posed to render service did not appear to take even themselves seriously.

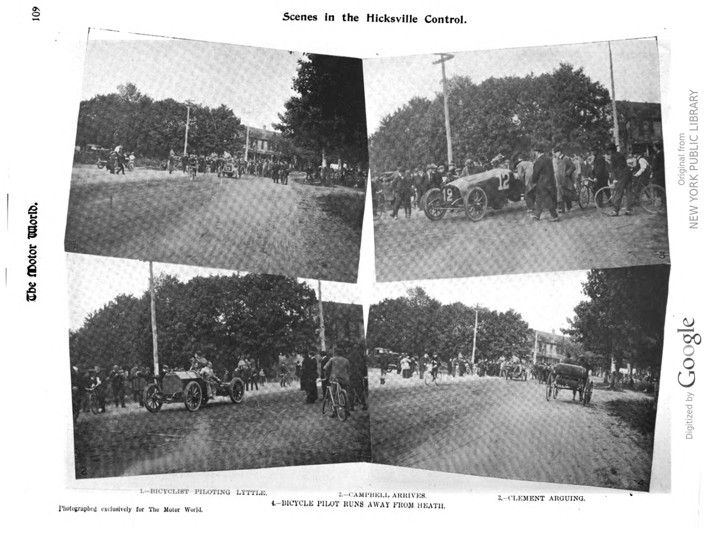

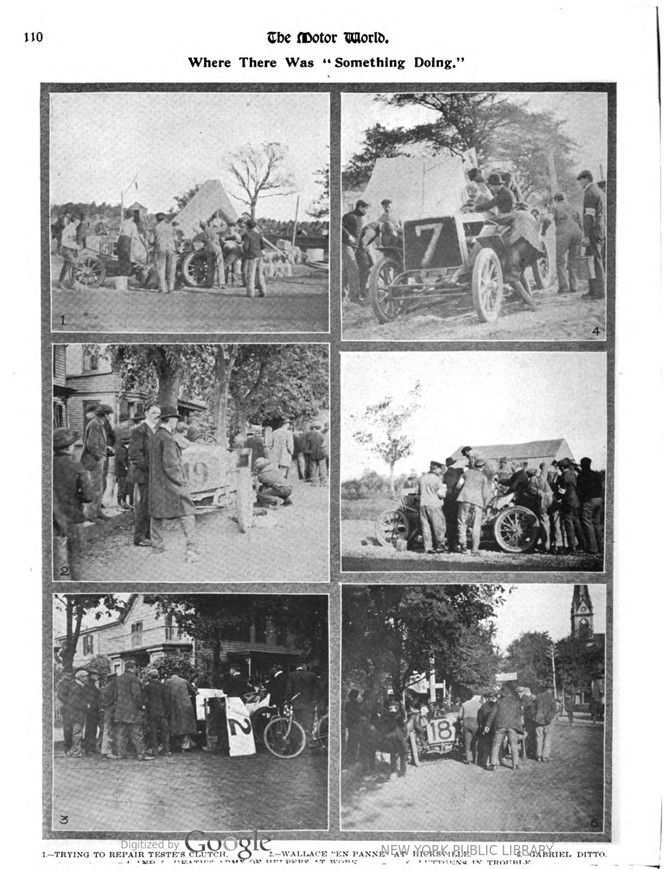

Of the nineteen entrants all started, save one, at the times scheduled. The exception was Alfred G. Vanderbilt’s Italian car, driven by Paul Sartori. It was due to start at 6:18. It actually started at 8:20:14. In the interim, Sartori was three miles away, straining might and main, to right a balky motor. If Albert G. ever had any hope of having his name inscribed on the great silver goblet given by his elder brother, the hope died early, for even as Sartori started he was disqualified. He violated the rules by making a flying start and was „called off“ by telephone at Hicksville, some five miles distant. There was an argument over the ‚phone lasting eleven minutes, which resulted in the lifting of the ban, and Sartori restarted. His clutch, however, went wrong, and he stopped „for keeps“ about ten miles further on.

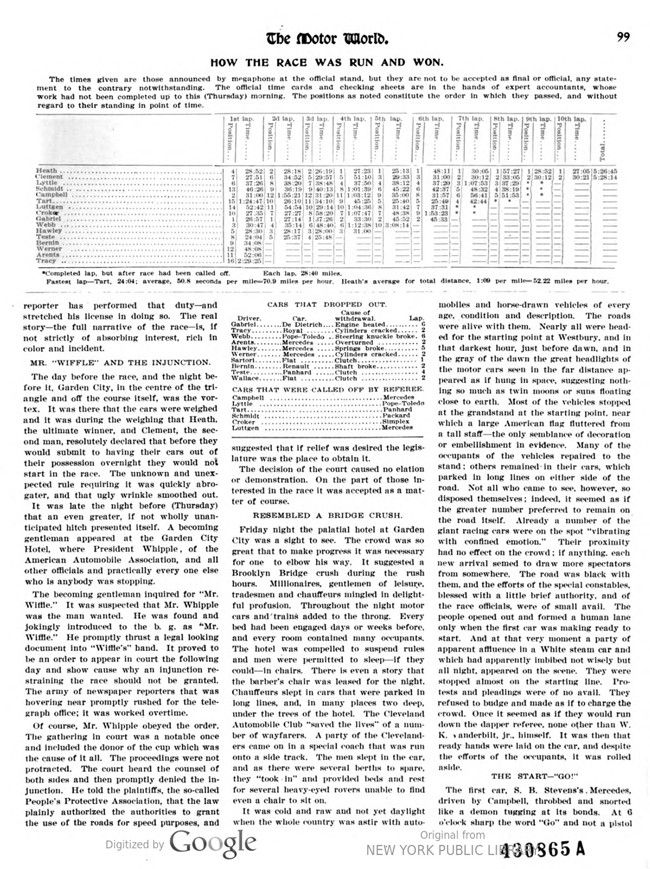

The starters, their official numbers, their order and time of starting follows:

No. Driver. Make and Representing. Time of start.

horsepower.

1. A. L. Campbell.. 60 Mercedes Germany …. 6.00

2. Fernan Gabriel… 90 Panhard France …… 6.02

3. Joseph Tracy….. 40 Royal United States. 6.04

4. A. C. Webb…… 60 Toledo United States. 6.06

5. Geo. Arents, jr… 60 Mercedes Germany ….. 6.08

6. H. H. Lyttle….. 24 Toledo United States. 6.10

7. George Heath…. 90 Panhard France 6.12.

8. E. E. Hawley…. 60 Mercedes Germany 6.14

9. Wilhelm Werner 90 Mercedes Germany 6.16

10. Paul Sartori…… 60 Fiat…….. Italy 8.20.14

11. M. G. Bernin 90 Renault France 6.20

12. Albert Clement 90 Clement France 6.22

14. M. Tart……….. 90 Panhard France 6.24

15. George Teste 90 Panhard France 6.26

16. Charles Schmidt 30 Packard United States 6.28

17. Frank Croker…..75 Simplex United States 6.30

18. J. Luttgen…….. 60 Mercedes Germany 6.32

19. William Wallace 90 Fiat Italy 6.34

Immediately the last car was dispatched the crowd again took possession of the road. Friends seated in cars left their cars and visited friends in the grandstand; friends in the grandstand left the stand and visited friends in the cars. Acquaintances in neither cars nor stand met and chatted on the road or at the roadside. It was like a huge picnic – an effect which was heightened when hampers were opened in response to the calls of the inner man-and inner woman, for womankind was well represented, and during the chill morning hours remained heavily muffled in bearskins and furs, adding to the picturesqueness of the scene. The officials seemed legion. They were everywhere, and it appeared that every color of the rainbow had been called on to afford distinctiveness to the brassards which each wore on his arm; each man’s wide silken ribbon seemed of a different hue, and each bore his particular title, and the caption „The W. K. Vanderbilt, Jr., Cup“-not „Cup Race,“ just plain „Cup.“

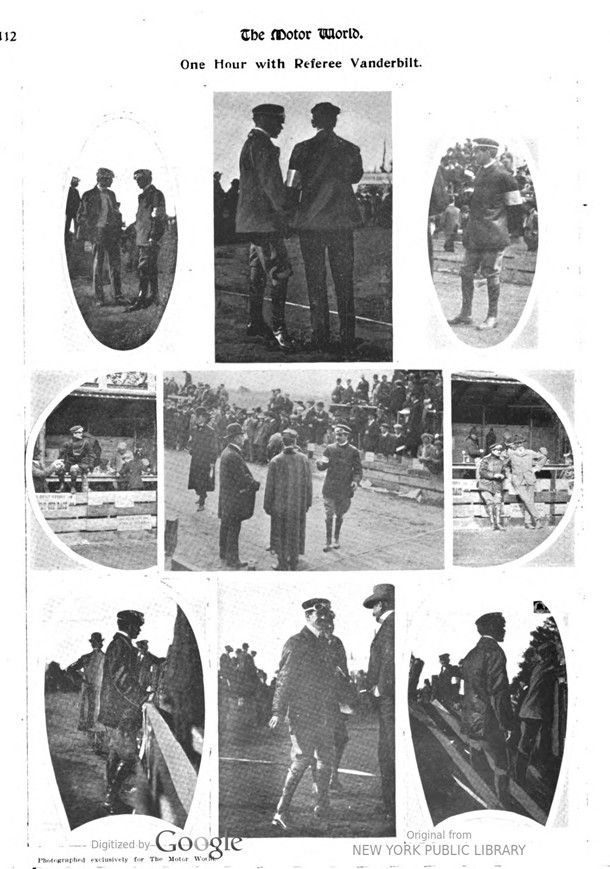

THE REFEREE.

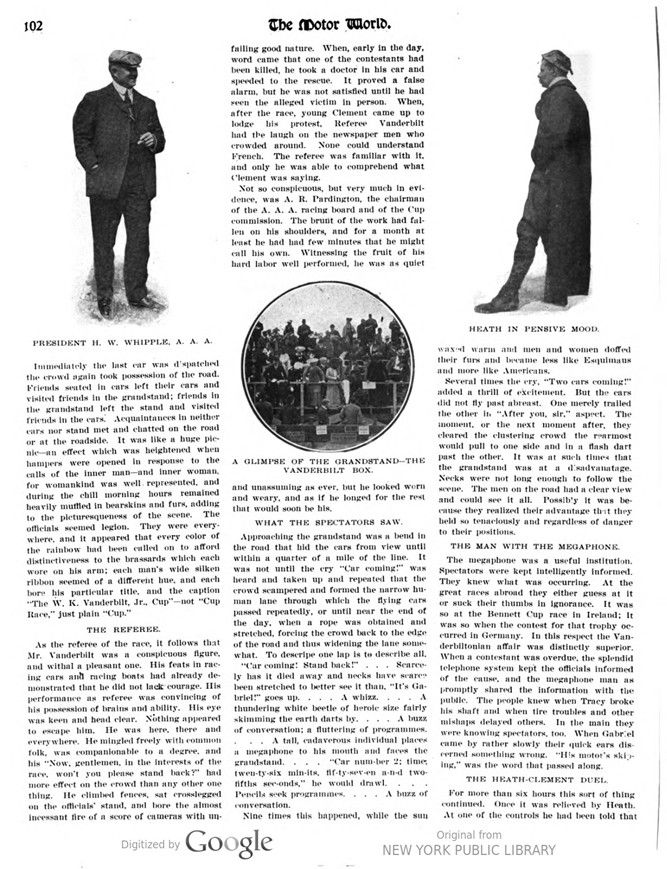

As the referee of the race, it follows that Mr. Vanderbilt was a conspicuous figure, and withal a pleasant one. His feats in racing cars and racing boats had already demonstrated that he did not lack courage. His performance as referee was convincing of his possession of brains and ability. His eye was keen and head clear. Nothing appeared to escape him. He was here, there and everywhere. He mingled freely with common folk, was companionable to a degree, and his „Now, gentlemen, in the interests of the race, won’t you please stand back?“ had more effect on the crowd than any other one thing. He climbed fences, sat cross-legged on the officials‘ stand, and bore the almost incessant fire of a score of cameras with unfailing good nature. When, early in the day, word came that one of the contestants had been killed, he took a doctor in his car and speeded to the rescue. It proved a false alarm, but he was not satisfied until he had seen the alleged victim in person. When, after the race, young Clement came up to lodge his protest, Referee Vanderbilt had the laugh on the newspaper men who crowded around. None could understand French. The referee was familiar with it, and only he was able to comprehend what Clement was saying.

Not so conspicuous, but very much in evidence, was A. R. Pardington, the chairman of the A. A. A. racing board and of the Cup commission. The brunt of the work had fallen on his shoulders, and for a month at least he had had few minutes that he might call his own. Witnessing the fruit of his hard labor well performed, he was as quiet and unassuming as ever, but he looked worn and weary, and as if he longed for the rest that would soon be his.

WHAT THE SPECTATORS SAW.

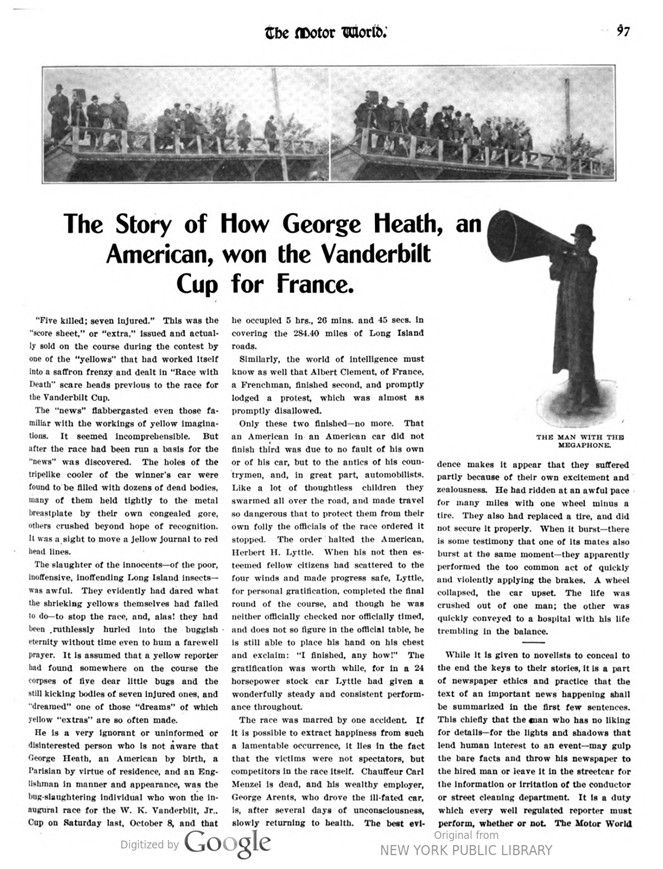

Approaching the grandstand was a bend in the road that hid the cars from view until within a quarter of a mile of the line. It was not until the cry „Car coming!“ was heard and taken up and repeated that the crowd scampered and formed the narrow human lane through which the flying cars passed repeatedly, or until near the end of the day, when a rope was obtained and stretched, forcing the crowd back to the edge of the road and thus widening the lane some- what. To describe one lap is to describe all. „Car coming! Stand back!“ . . Scarcely has it died away and necks have scarce been stretched to better see it than, „It’s Gabriel!“ goes up. A whizz…. A thundering white beetle of heroic size fairly skimming the earth darts by. A buzz of conversation; a fluttering of programmes. A tall, cadaverous individual places a megaphone to his mouth and faces the grandstand. „Car num-ber 2; time, twen-ty-six min-its, fif-ty-sev-en a-n-d two- fifths sec-onds,“ he would drawl. Pencils seek programmes. conversation. A buzz of Nine times this happened, while the sun waxed warm and men and women doffed their furs and became less like Esquimaus and more like Americans.

Several times the cry, „Two cars coming!“ added a thrill of excitement. But the cars did not fly past abreast. One merely trailed the other in „After you, sir,“ aspect. The moment, or the next moment after, they cleared the clustering crowd the rearmost would pull to one side and in a flash dart past the other. It was at such times that the grandstand was at a disadvantage. Necks were not long enough to follow the scene. The men on the road had a clear view and could see it all. Possibly it was because they realized their advantage that they held so tenaciously and regardless of danger to their positions.

THE MAN WITH THE MEGAPHONE.

The megaphone was a useful institution. Spectators were kept intelligently informed. They knew what was occurring. At the great races abroad they either guess at it or suck their thumbs in ignorance. It was so at the Bennett Cup race in Ireland; it was so when the contest for that trophy occurred in Germany. In this respect the Vanderbiltonian affair was distinctly superior. When a contestant was overdue, the splendid telephone system kept the officials informed of the cause, and the megaphone man as promptly shared the information with the public. The people knew when Tracy broke his shaft and when tire troubles and other mishaps delayed others. In the main they were knowing spectators, too. When Gabriel came by rather slowly their quick ears discerned something wrong. „His motor’s skiing,“ was the word that passed along.

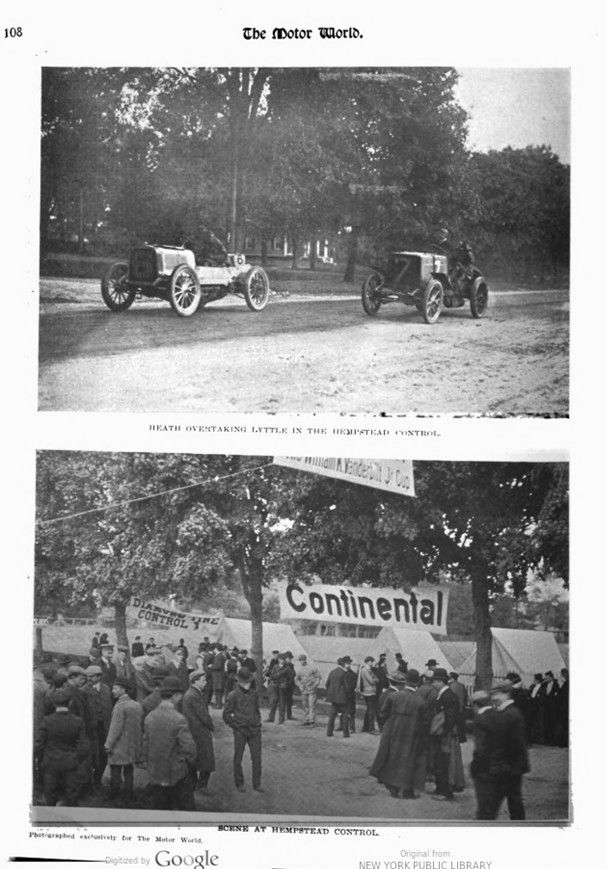

THE HEATH-CLEMENT DUEL.

For more than six hours this sort of thing continued. Once it was relieved by Heath. At one of the controls, he had been told that he was leading. When he passed the grandstand, he removed a hand from the steering wheel and saluted. The crowd responded with mild applause. Then Heath had his tire troubles, and the young Frenchman, Clement, tucked snugly in what looked like the footgear of the „Old Woman who lived in a shoe,“ began to crawl up. The crowd showed its excitement. On the eighth lap Clement forged ahead. He passed the official stand more than two minutes to the good. The crowd applauded, and not a few of the many Frenchmen who were in evidence at all points betrayed symptoms of incipient hysteria. The French lad was still ahead at the close of the ninth lap-1:48 to be exact.

HEATH WINS AND KEEPS RIGHT ON.

Heath had picked up a few of his lost seconds, but it did not now seem that he would win. It all seemed over but the shouting. But the crowd had its doubts, and remained on edge until word came from Queens that at that point Clement was one minute behind. There was an animated buzz of relaxation, and when Heath hove in sight he was acclaimed heartily. It was the first outburst of real enthusiasm. The referee and donor of the cup forgot his position and joined in it. Heath displayed no consciousness of it all. He drove full tilt up to the line and over it. If in his makeup, there is aught of the „grandstand player“ he gave no evidence of it. Each second was doubtless too precious. He gave no heed to the cheers, if, indeed, he heard them. Without slackening his pace a jog, he went on. He did not stop until he reached his garage, five miles dis- tant. That is why a number of checkers were mystified and why Heath appears on their sheets as having passed their stations eleven times. Never was there a more modest victor.

CLEMENT LODGES HIS PROTEST.

It seemed much longer than it really was before the „Car coming!“ cry denoting Clement’s approach was heard. There were still others making the rounds of the course, but they were far behind, and the crowd had now no thoughts of or for them. The loser’s lot is rarely a happy one. But he had been such a good loser and put up such a grand fight for 250 miles at least that when Clement dashed across the line he was as wildly cheered as Heath. When, ten minutes later, he came back on foot, supported on either side by friends and with a retinue of jabbering Frenchmen in his wake, which was constantly being increased by curious Americans, the crowd gave him an ovation. But Clement seemed deaf, indeed, he looked like a wild man. He had doffed his leather head-gear and his goggles, and only the upper part of his face was white; the rest of it was black with grease and grime. His eyes rolled and he was wildly excited. He sought the referee and found him in the press box.

THE CROWD BREAKS; RACE STOPPED.

The word passed that he was lodging a protest. It was enough for the crowd. It broke like a drove of sheep scampering after a bell wether and charged the press box, where Referee Vanderbilt and young Clement were exchanging a rapid fire of French. While the road was thus congested a couple of cars parked in the field at the roadside pulled out on the course and headed in the direction of New York; others immediately „took the cue“ and did likewise. The officials and constables, or some of them, made manful efforts to beat back the tide. They pleaded and stormed and swore, but to no purpose. At any moment one of the giant racing cars might swing around the bend in the road. A frightful tragedy was imminent, or at any rate was being invited. The crowd cared naught, and those who of right and decency were expected to help and obey the officials flouted them. The automobilists simply blocked the road with their cars. There was no stopping them. The race officials were at their wits‘ end. But quickly it was decided to stop the racers at all hazards. Every telephone to every control and Corner was brought into use. „Stop the men at all costs!“ was the message sent.

Again, was God good to that heedless crowd All the racers were stopped before they reached the surging mass of humanity, and its skin remained whole. But it was a bitter pill for Lyttle and Schmidt and Croker and the others. Officially the road was open to them for more than an hour, and to the men bent on finishing, „no matter how,“ it is gall and wormwood to be forced to quit. It roiled Lyttle so greatly that after the crowd had thinned, he continued around the course for the tenth time that he might say that he had completed the whole distance. But no official cognizance of it was taken.

THE PROTEST AND ITS REJECTION.

When Clement was made to understand that he must reduce his protest to writing, he did so in this communication addressed to the referee:

„Under Article No. 56 of the road race rules, I beg to submit for your consideration the following protest for some penalization on time and loss of time which I sustained on account of timers and checkers applying erroneously some of the rules of the race.

„First, when arriving at Hempstead on my eighth lap the timer gave me my card. My chauffeur then did give some attention to my motor. The timer, seeing this, protested that I had no right to do any sort of repairs while in neutralization, and asked me to hand him back my timecard. I at first refused, but fearing unknown decisions I handed back my card.

„The timers counted carefully the time I spent fixing up my motor and put in my box the newly corrected card. As I had full right to attend to my motor personally while inside the neutralization, I claimed that this change in my time was unduly done, and to have the same deducted from my total time. „Second-At Hicksville, while I was at the line ready to leave, I wanted to spend the remaining time in giving some little attention to my motor, but the timer absolutely prevented me, and in spite of my protests stated most strongly that he would not permit me to do so. I therefore had to push my car out of the control to attend to my business.

„In not respecting my rights the timer has been the cause of my losing the remaining time to expire before my order to leave plus the time I spent in pushing my car out of control after being given my start. This occurred twice at the same place, and cost me one minute, at least.“

At about midnight Referee Vanderbilt announced the disallowance of the protest in this language:

„In answer to the first specification of M. Clement’s protest I have decided as follows: That M. Clement had no right to stop and make repairs undertaken after entering and before proceeding through the control; having been warned by judges and timekeepers, his original card was recalled and properly corrected on his failure to comply with instructions, and that M. Clement, if he had followed the order given, would have consumed, as required by the governing regulations, six minutes in passing through the confines. Therefore, his claim for lost time in making repairs after due instruction of judges and timekeepers is disallowed.

„In answer to the second specification, alleging that he was obliged to push his car from the exit of the control, the evidence does not sustain the statement.“