Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Motor Age, Vol. XXXVII, No. 23, June 3, 1920, page 7 – 12 / In This Issue: The Indianapolis Race

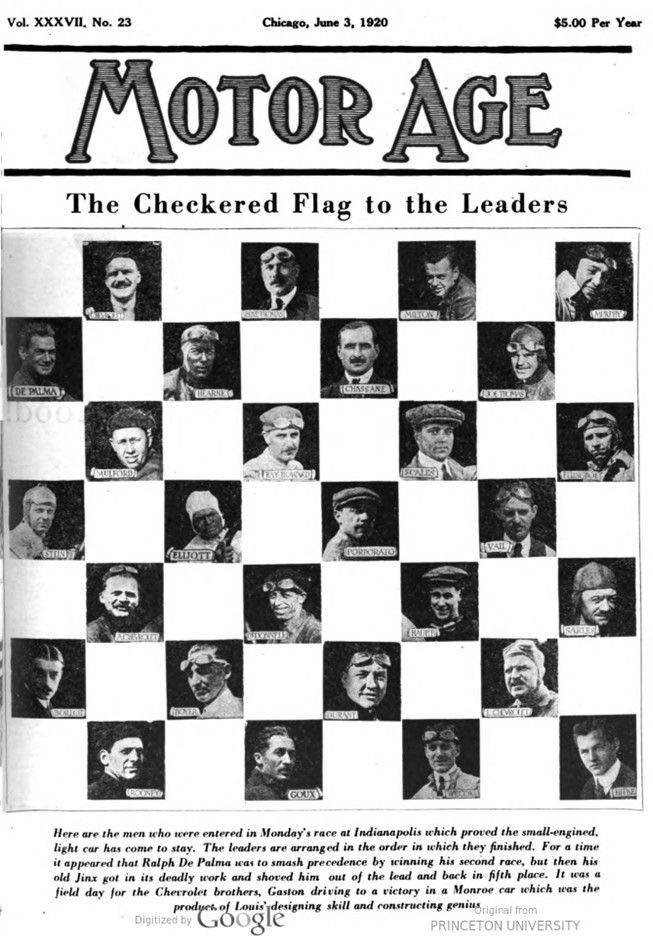

The Checkered Flag to the Leaders

CHEVROLET – RENE THOMAS – MILTON – MURPHY DE PALMA – HEARNE CHASSANE — JOE THOMAS – MULFORD – RAY HOWARD – SCALES – ELLINGBOE – STEIN – ELLIOTT – PORPORATO – VAIL – A. CHEVROLET – O’DONNELL – HAUPT – SARLES – BOILLOT – BOYER – DURANT- L. CHEVROLET – ROONEY – GOUX – WILCOX – HITKE

Here are the men who were entered in Monday’s race at Indianapolis which proved the small-engined, light car has come to stay. The leaders are arranged in the order in which they finished. For a time, it appeared that Ralph De Palma was to smash precedence by winning his second race, but then his old Jinx got in its deadly work and shoved him out of the lead and back in fifth place. It was a field day for the Chevrolet brothers, Gaston driving to a victory in a Monroe car which was the product of Louis‘ designing skill and constructing genius

The Small Engine Has Made Good!

Performance of Racers at Indianapolis.

This Year Proves the Soundness of New Designing and Construction Theories.

BY LAMBERT G. SULLIVAN

INDIANAPOLIS, May 31 – The light weight, small engined racing car made good here to-day, It went through a racking, grinding 500 miles of extreme speed in a way which delighted and astonished even the most enthusiastic adherents of the light car idea. Gaston Chevrolet, driving an American-built Monroe car, won the race at a rate of 88.16 m. p. h., but Gaston’s victory was of minor importance as compared with the wonderful showing made by the small car in its first trial.

All Teams Get Honors

To be more specific, every team of cars which was ready for the race went through with flying colors. The Ballots, Frontenacs, Monroes and Duesenbergs, to say nothing of individual cars carrying other engines, performed in a way which demonstrated clearly that the designers of to-day are able to get quite as much speed, quite as much endurance out of the lightweight, small engined cars as their predecessors were out of much larger machines.

Six teams of cars, in all, started in the race, and four of them finished creditably. Of the two failures-the Peugeot and the Gregoire-the latter was manifestly not ready to take part in the race and should not even have been permitted to start. The Gregoires were thrown together in so great a hurry that even the qualifying laps revealed defects in their design, obvious even to the uninitiated. The Peugeot failed because of designing defects-defects which were admitted even before the race by the Peugeot drivers, but which they had not the time to remedy.

All in all, it was a great race, not spectacular in any sense of the word, but a real trial of the cars entered. Considered from a sporting standpoint, the race was not nearly as good as some of its predecessors at the Hoosier oval: considered in the light of its importance to the future of the automobile industry, it is unsurpassed. For it assured the future of the light car and proved that light cars can be built which are in every way the equal of their heavier brothers of the present.

Chevrolet Gets Highest Credit

To Louis Chevrolet and his brother Gaston will go the major honors of the day, but there are plenty of honors to go around and Ernest Ballot and Fred Duesenberg are honestly entitled to a full share of the reward for the, wonderful showing of the new cars. Louis and Gaston won the race, but Ballot and Duesenberg showed conclusively that they have developed small engines to just as great a degree of perfection as the winners.

It is a source of some pride to know that the car which won the race is an American product, the first American winner since the historic victory of Joe Dawson in a National in 1912. The Monroe, as well as the Frontenac, were designed and built by Louis Chevrolet, an American citizen, and embodied the ideas that their builder has imbibed in his long career as a racing driver in the United States. The Monroes and Frontenacs were identical in construction and, although they competed under different names, should be regarded as being truly one entry.

Ballot again proved himself capable of designing cars for new conditions. That a Ballot did not win the race was the fault of carelessness rather than any- thing else, for had not Ralph De Palma permitted himself to run out of fuel far from the pits, it is almost certain the French car would have won. Even without the victory, however, Ballot has good cause to feel satisfied with his achievement, for every one of the three cars he entered in the race finished within the first ten.

Duesenbergs Make Showing

Fred Duesenberg also had a memorable achievement. Four Duesenbergs were at the line for the start of the race and three of them finished within the money. It seemed as if the Duesies were not quite as fast as the Ballots and the Chevrolet creations, but their performance impressed those who saw the race that they were extremely reliably constructed and that they were capable of standing a great deal of work.

Far less engine trouble was experienced by the new cars than had been anticipated by technical men. It was their general belief that few of the cars in the race would escape without any serious trouble of this sort. It eventuated, however, that there was little more engine trouble than has usually been the case even with cars which have been thoroughly tried out.

The chief trouble experienced by the cars was the breakage of parts which ordinarily go through races without trouble. This was directly due to the „metal fatigue“ occasioned by the hurry in which the cars were put together and are regarded by technical men as being of slight importance. The basic correctness of the small car idea having been proved to be correct, minor defects, such as those developed in the race, are merely a matter of care in construction and selection of materials.

W. F. Bradley, European representative of MOTOR AGE, was agreeably surprised with this lack of trouble. Before the race he declared that neither of the Gregoire cars was ready for the grind and should not be counted seriously. The Peugeots, he declared, had numerous defects in design and would not be serious factors, while the Bal- lots alone would be given a fair trial. Mr. Bradley frankly stated before the race that until the race was run, it would be impossible to pass judgment on the Ballots. After the race he declared that he was astonished that so little engine trouble had been encountered and was vastly pleased with the excellent showing in that all three of the Ballots finished inside the money.

The American cars, which had even a more severe test of their ability than the French, inasmuch as there were three complete teams and two different designs under trial, while it would be just to hold the results of the race a test of only one European, fared fully as well as the French. For the sake of brevity, the Monroes and Frontenacs may be considered as one team, for they were identical in design and construction, both the product of Louis Chevrolet’s designing skill and mechanical genius.

There were seven of the Monroe-Frontenac cars in the race and of these two finished among the first ten. Of the remainder, not one was forced out of the race by engine trouble, the causes of their withdrawal being rather defective or overstrained materials. The fact that two of these cars were forced out by breaks in the steering gear and that two more were forced out because of accidents occurring because of the difficulty in handling the mounts would seem to point out to Chevrolet a defect in his design which he may be able to remedy for later races.

O’Donnell Breaks Oil Line

Fred Duesenberg upheld his reputation for building engines of staunchness by the excellent work of the team of four cars entered under his colors. Three of the four Duesies finished in the money, third, fourth and sixth places falling to him. The only Duesenberg car which failed to finish the race was the one driven by Eddie O’Donnell, which was forced out after more than three-quarters of the race had been completed, because of a broken oil line.

The teamwork of steadiness of the Duesenberg’s was one of the big features of the day. Lap after lap the yellow cars rolled around the track, Milton and Murphy sticking together in one pair and Hearne and O’Donnell in another. It seemed as if they were running on a schedule of the utmost exactitude, for their appearances in front of the judges‘ stand were almost clocklike in their regularity and steadiness. The fact that O’Donnell was forced to quit the race was the only cloud in a perfect day for Mr. Duesenberg.

Crowd Estimated at 120,000

Considered strictly as a sporting event, the race left much to be desired. It was seen by what probably was the largest crowd which ever saw a race at the Hoosier oval, an estimate of better than 120,000 attendance being issued by the Speedway management after the race. Ideal conditions prevailed for the race, the weather being a trifle cooler than is ordinarily experienced at the Memorial Day classic, while there was just enough dampness in the atmosphere to aid carburetion.

For the first 100 miles of the race, there was plenty of interest to keep the spectators alert. Ralph De Palma and Joe Boyer hooked up in a duel which kept the big crowd constantly on the alert, but after the century mark had been passed, there were not enough brushes to make the race really appeal to the crowd. After De Palma and Boyer had fought their duel in the first 100 miles, every change of leadership came because the leader was forced to the pits, permitting the second car to pass him.

Ralph De Palma had more than his share of bad luck, but a trifle more care probably would have won the race for him, despite all his misfortunes. He twice had tire trouble in the first 200 miles of the race, both coming at crucial times, but was remarkably fortunate in escaping trouble for the last 300 miles, and had he stopped and made assurance doubly sure by taking on fuel when he had an advantage of more than two laps over his closest competitor, he probably would have flashed over the wire in first place.

Careful Race by Chevrolet

Chevrolet won the race by as consistent an exhibition of driving as has ever been seen on an American track. He never was in the lead until he took it near the close, when De Palma ran out of fuel, but at the same time he never was worse than fourth, and he set and maintained a pace which he believed would win for him, ignoring all challenges from other drivers to engage in brushes. It was this steadiness and consistency which won for him and he showed this steadiness even to a greater extent when he stopped only ten miles from the finish to replenish his gas, oil and water in order to avoid falling into De Palma’s blunder.

Action of Indianapolis merchants in adding the sum of $20,000 to the regular Speedway purse, to be distributed in prizes of $100 to the leader at the end of each lap in the race, undoubtedly speeded it up, especially at the start. Several of the drivers in the race were fearful that their cars would not be able to make the full 500 miles and they were resolved to earn as much as possible in the way of lap prizes as long as their cars held together. This caused almost the entire field to go out and „beat it“ from the start, and the pace was much faster than it would have been had there been no lap money at stake.

There was, fortunately, a complete absence of the accidents which marred last year’s race. Several of the cars ran off the track and into the retaining wall and Ira Vail, who took Boyer’s seat in the latter part of the race, overturned, but he and his mechanician escaped serious injuries. Considering the remarkable prevalence of steering gear trouble in the race, the fact that no one was injured is one of the most remarkable features of the race.

De Palma ran into his bad luck almost at the very start of the race. When the cars wheeled across the wire at the end of the pacing lap, it was seen that De Palma’s right rear tire was flat and he was forced to drive into the pits for a change, even before he had made his first lap. This mischance threw him into seventeenth place and forced him to go out and beat it from the start to catch up with his competitors.

The lure of the lap money early manifested itself, for the drivers pushed their cars to the utmost right from the start, each eager to roll up a number of lap leaderships and swell his winnings. Joe Boyer’s car proved the fastest of the field in this jockeying and he quickly drove into the leadership, relinquishing this honor in only two of the first thirty-eight laps, Art Klein nipping him on one lap and Jean Chassagne on the other.

While Boyer was rolling up this big total of lap money, De Palma was behind him, driving like a fiend to make up the ground he had lost in his tire change in the first lap. The big white car crept up foot by foot and yard by yard on the green one, until at the end of the thirty-ninth lap it finally overtook and passed the leader.

For only two laps did De Palma pick up the $100, however, another stop for tires and gasoline and oil giving back the position to the Frontenac driver, Boyer continued to make the most of his opportunity and never was again headed until his first tire change gave Rene Thomas a chance to pass him and cross the line ahead of him for seven successive laps.

Photo captions.

Page 8.

An American car the winner at last! Gaston Chevrolet in the Monroe, the first United States built car which has won an Indianapolis Derby since 1912, and in the circle, Louis Chevrolet the veteran race driver who designed and built the machine.

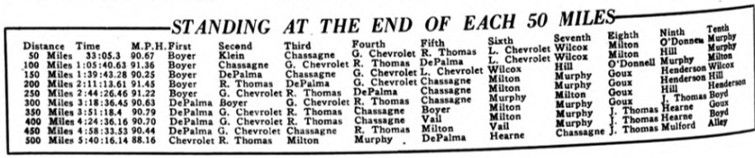

STANDING AT THE END OF EACH 50 MILES

Page 9.

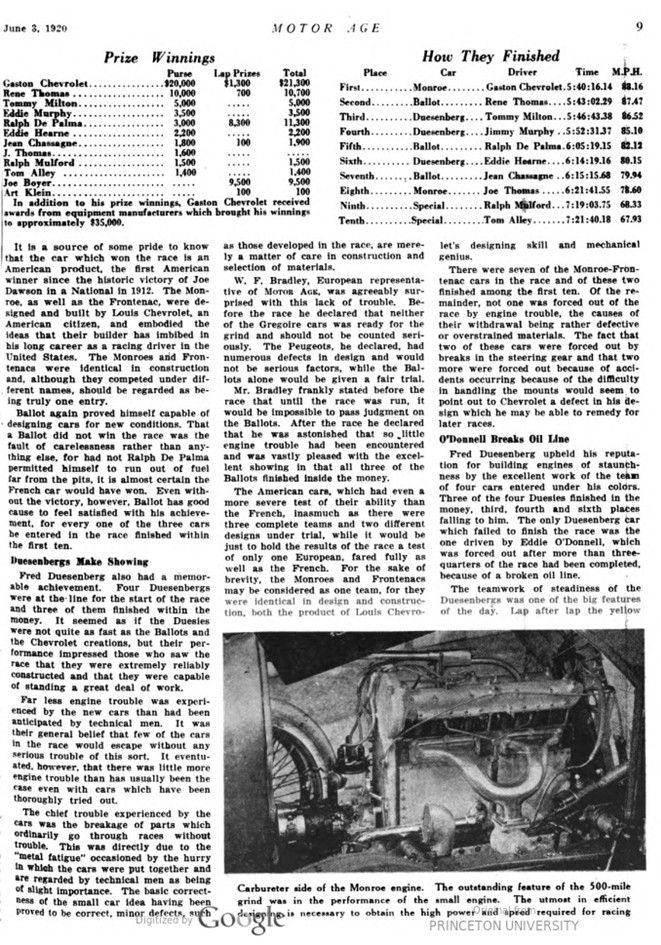

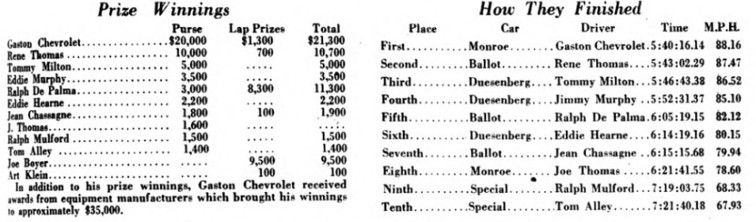

Prize Winnings, How They Finished

Carbureter side of the Monroe engine. The outstanding feature of the 500-mile grind was in the performance of the small engine. The utmost in efficient designing is necessary to obtain the high power and speed required for racing

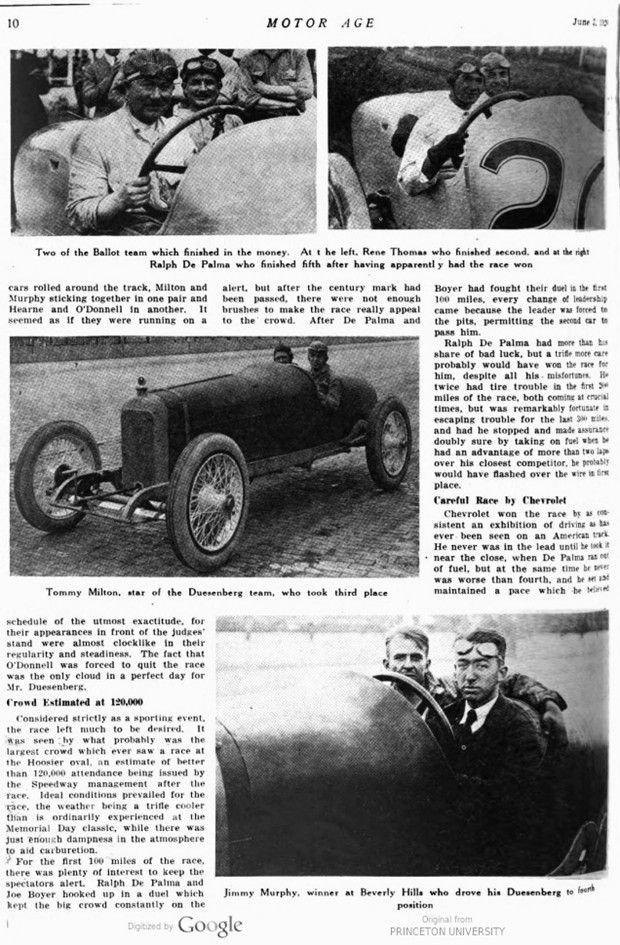

Page 10.

Two of the Ballot team which finished in the money. At t he left, Rene Thomas who finished second, and at the right Ralph De Palma who finished fifth after having apparently had the race won

Tommy Milton, star of the Duesenberg team, who took third place

Jimmy Murphy, winner at Beverly Hills who drove his Duesenberg to fourth position

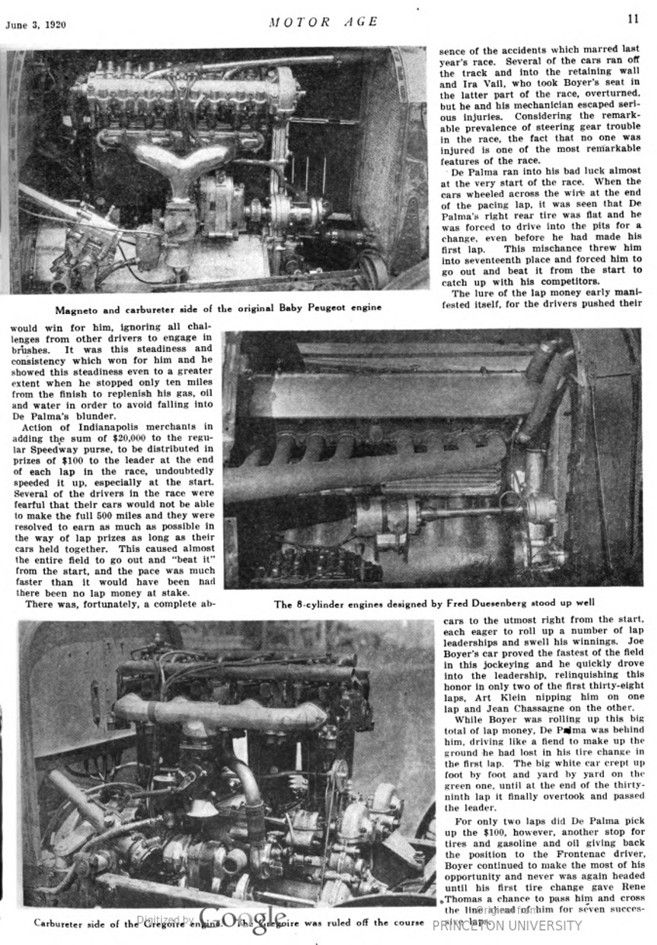

Page 11.

Magneto and carbureter side of the original Baby Peugeot engine

The 8-cylinder engines designed by Fred Duesenberg stood up well

Carbureter side of the Gregoire engine. The Gregoire was ruled off the course

Page 12.

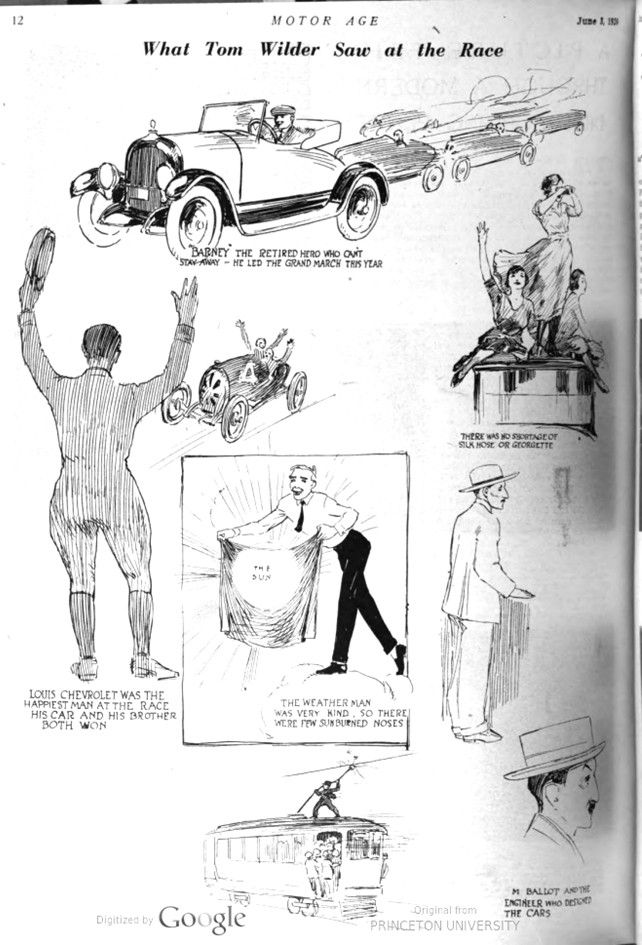

What Tom Wilder Saw at Saw at the Race

“BARNEY” THE RETIRED HERO WHO CAN’T STAY AWAY – HE LED THE GRAND MARCH THIS YEAR

LOUIS CHEVROLET WAS THE HAPPIEST MAN AT THE RACE. HIS CAR AND HIS BROTHER BOTH WON

THE SUN – THE WEATHER MAN WAS VERY KIND, SO THERE WERE FEW SUN BURNED NOSES

THERE WAS NO SHORTAGE OF SILK HOSE OR GEORGETTE

M. BALLOT AND THE ENGINEER WHO DESIGNED THE CARS