Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Motor Age, Vol. XL (40), No. 5, August 4, 1921

Racing Engines of the Future

Probabilities Are the 122 Cu. In. or 2-Liter Engine Will Be as Fast or Faster Than Its Predecessors-High Crankshaft Speed Demands Best Materials and Design

THE fact that the management of the Indianapolis speedway has seen fit to restrict the 1923 500-mile Hoosier classic to cars fitted with engines of not greater than 122-cu. in. piston displacement, has been productive of much discussion as to whether or not cars fitted with such small engines will be as fast and stand up as well on the track as their predecessors of 183-cu. in. and larger.

Some light can be thrown on this subject when past performances of the cars are studied. Since the first running of the Indianapolis race the piston displacement limit has been changed four times – five times, including the present ruling of the management regarding the 1923 cars.

At the same time, the average speed has not decreased along with the reduction in piston displacement, but on the contrary has increased. The record for the distance is held by a car with a piston displacement of 274-cu. in., this being the Mercedes driven by Ralph De Palma in 1915. The car covered the 500 miles at an average speed of 89.84 m.p.h.

However, Tom Milton, in a Frontenac of 182.5-cu. in. piston displacement, covered the distance in this year’s race at an average speed of 89.62 m.p.h., or only .22 m.p.h. slower. In other words, the Frontenac, a car fitted with an engine of 91.5 less cu. in. displacement, practically was as fast as the Mercedes. Perhaps had Milton crowded his car a little more he easily might have set a new record for the race. In fact, had the Ballot driven by De Palma this year not fallen by the wayside, it is a certainty the car would have set a new record, inasmuch as it was breaking all previous marks up to the time of its withdrawal.

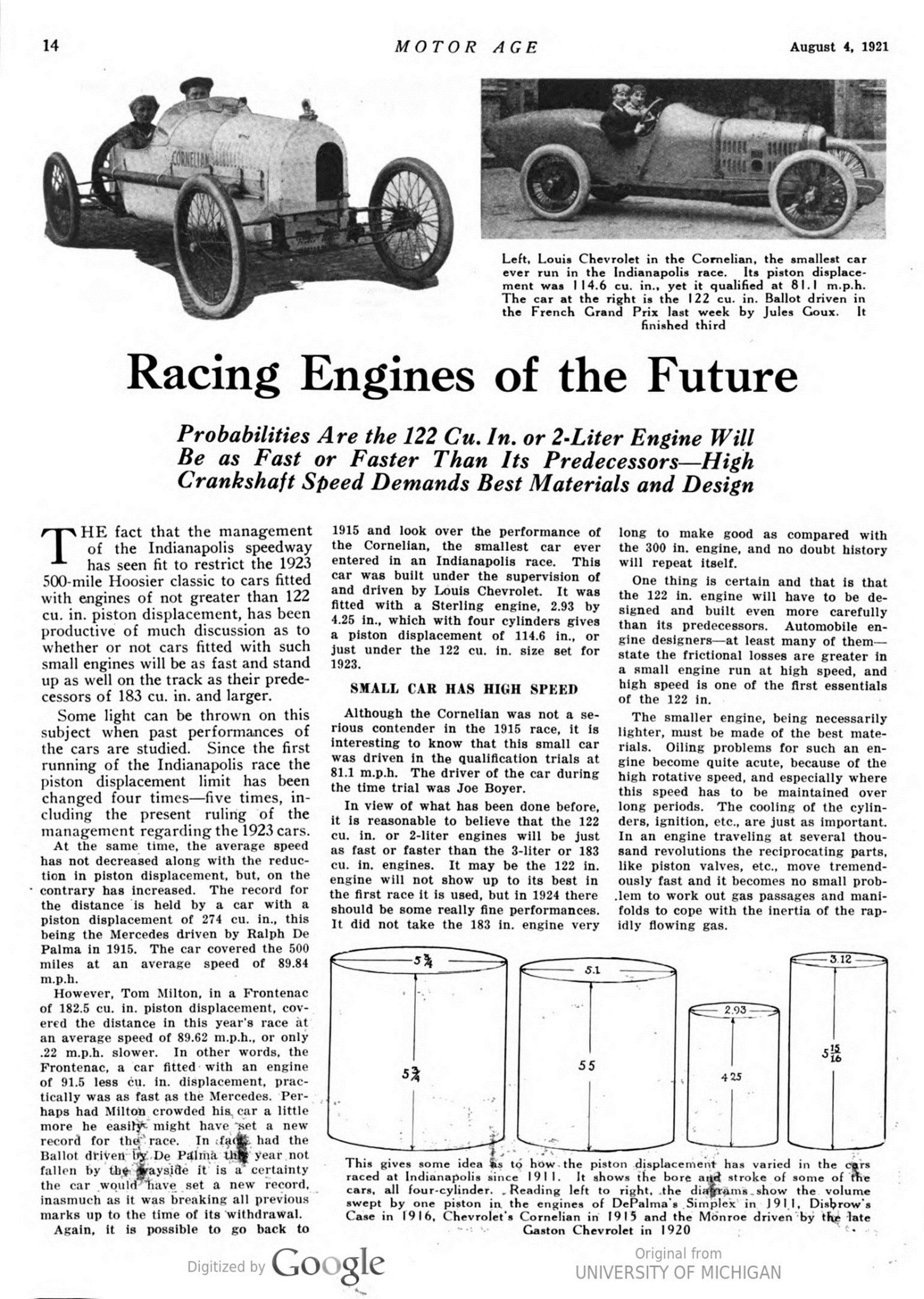

Again, it is possible to go back to 1915 and look over the performance of the Cornelian, the smallest car ever entered in an Indianapolis race. This car was built under the supervision of and driven by Louis Chevrolet. It was fitted with a Sterling engine, 2.93 by 4.25 in., which with four cylinders gives a piston displacement of 114.6 in., or just under the 122-cu. in. size set for 1923.

SMALL CAR HAS HIGH SPEED

Although the Cornelian was not a serious contender in the 1915 race, it is interesting to know that this small car was driven in the qualification trials at 81.1 m.p.h. The driver of the car during the time trial was Joe Boyer.

In view of what has been done before, it is reasonable to believe that the 122-cu. in. or 2-liter engines will be just as fast or faster than the 3-liter or 183-cu. in. engines. It may be the 122 in. engine will not show up to its best in the first race it is used, but in 1924 there should be some really fine performances. It did not take the 183 in. engine very -54 5.1 It long to make good as compared with the 300 in. engine, and no doubt history will repeat itself.

One thing is certain and that is that the 122 in. engine will have to be de- signed and built even more carefully than its predecessors. Automobile engine designers – at least many of them – state the frictional losses are greater in a small engine run at high speed, and high speed is one of the first essentials of the 122 in.

The smaller engine, being necessarily lighter, must be made of the best mate- rials. Oiling problems for such an engine become quite acute, because of the high rotative speed, and especially where this speed has to be maintained over long periods. The cooling of the cylinders, ignition, etc., are just as important. In an engine traveling at several thousand revolutions the reciprocating parts, like piston valves, etc., move tremendously fast and it becomes no small problem to work out gas passages and manifolds to cope with the inertia of the rapidly flowing gas.

Photo captions.

Page 14.

Left, Louis Chevrolet in the Cornelian, the smallest car ever run in the Indianapolis race. Its piston displacement was 114.6 cu. in., yet it qualified at 81.1 m.p.h. The car at the right is the 122 cu. in. Ballot driven in the French Grand Prix last week by Jules Goux. finished third

This gives some idea as to how the piston displacement has varied in the cars raced at Indianapolis since 1911. It shows the bore and stroke of some of the cars, all four-cylinder. Reading left to right, the diagrams show the volume swept by one piston in the engines of DePalma’s Simplex in 1911, Disbrow’s Case in 1916, Chevrolet’s Cornelian in 1915 and the Monroe driven by the late Gaston Chevrolet in 1920