Text and pictures with courtesy of Hathitrust.org; compiled by motorracinghistory

MOTOR – November 1905 – Page 39 – 44

The Race for the Vanderbilt Cup

BY HERBERT EVERETT

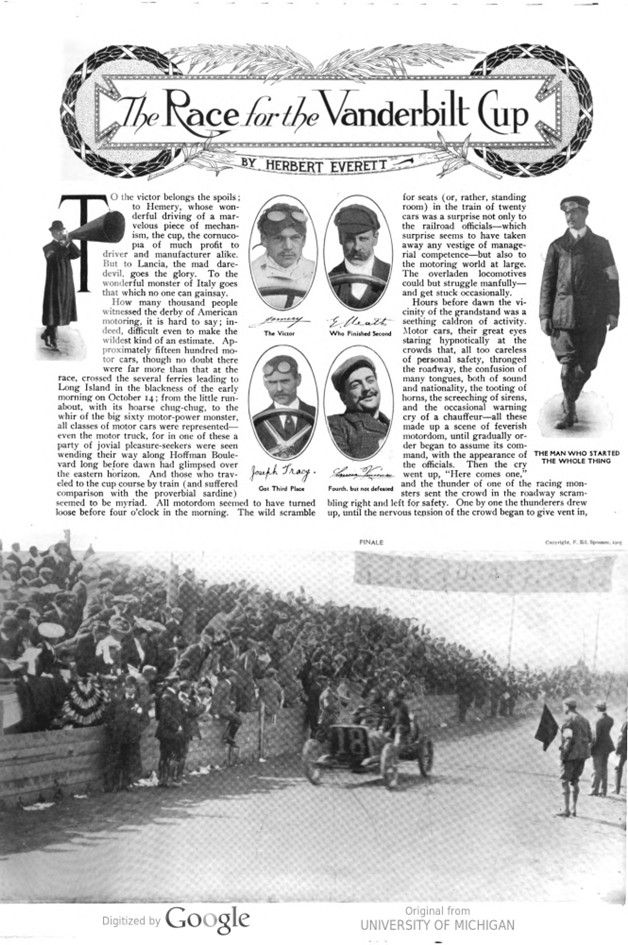

TO the victor belongs the spoils; to Hemery, whose wonderful driving of a marvelous piece of mechanism, the cup, the cornucopia of much profit to driver and manufacturer alike. But to Lancia, the mad daredevil, goes the glory. To the wonderful monster of Italy goes that which no one can gainsay.

How many thousand people witnessed the derby of American motoring, it is hard to say: indeed, difficult even to make the wildest kind of an estimate. Approximately fifteen hundred motor cars, though no doubt there were far more than that at the race, crossed the several ferries leading to Long Island in the blackness of the early morning on October 14; from the little runabout, with its hoarse chug-chug, to the whir of the big sixty motor-power monster, all classes of motor cars were represented – even the motor truck, for in one of these a party of jovial pleasure-seekers were seen wending their way along Hoffman Boulevard long before dawn had glimpsed over the eastern horizon. And those who traveled to the cup course by train (and suffered comparison with the proverbial sardine) seemed to be myriad. All motordom seemed to have turned loose before four o’clock in the morning. The wild scramble for seats (or, rather, standing room) in the train of twenty cars was a surprise not only to the railroad officials – which surprise seems to have taken away any vestige of managerial competence – but also to the motoring world at large. The overladen locomotives could but struggle manfully – and get stuck occasionally.

Hours before dawn the vicinity of the grandstand was a seething caldron of activity. Motor cars, their great eyes staring hypnotically at the crowds that, all too careless of personal safety, thronged the roadway, the confusion of many tongues, both of sound and nationality, the tooting of horns, the screeching of sirens, and the occasional warning cry of a chauffeur – all these made up a scene of feverish motordom, until gradually order began to assume its command, with the appearance of the officials. Then the cry went up, „Here comes one,“ and the thunder of one of the racing monsters sent the crowd in the roadway scrambling right and left for safety. One by one the thunderers drew up, until the nervous tension of the crowd began to give vent in after the fashion of American audiences, utter silence. Then the clerk-of-the-course drew Jenatzy to the line. Cheers! The short snaps of Starter Wagner’s arm as he told off the seconds was the focus of ten thousand eyes; and Jenatzy heard „ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three, two, go“; in went the clutch, and, like a flash, the race was on.

Then came Duray, with his great De Dietrich, rumbling like distant thunder; then Dingley in the pigmy Pope-Toledo. Then came Lancia, the favorite, tense, eager, fiery, with all the fire of the south, awaiting the word „Go,“ and when he heard it, it seemed he had almost disappeared. And so, they went one after one – Christie, No. 11, missing his start and being compelled to wait until all had made their adieus-until the officials, grouped in front of the grandstand, began to watch for the coming of the first car, when the French words, „qui vive,“ meant to the Anglo-Saxon mind all that it means to the French.

———-

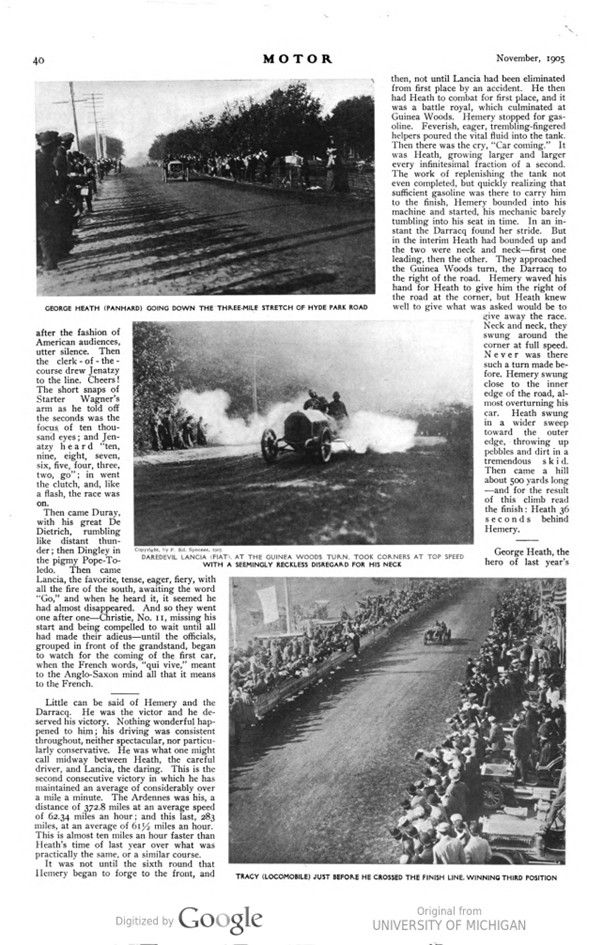

Little can be said of Hemery and the Darracq. He was the victor and he deserved his victory. Nothing wonderful happened to him; his driving was consistent throughout, neither spectacular, nor particularly conservative. He was what one might call midway between Heath, the careful driver, and Lancia, the daring. This is the second consecutive victory in which he has maintained an average of considerably over a mile a minute. The Ardennes was his, a distance of 372.8 miles at an average speed of 62.34 miles an hour; and this last, 283 miles, at an average of 61½ miles an hour. This is almost ten miles an hour faster than Heath’s time of last year over what was practically the same, or a similar course.

It was not until the sixth round that Hemery began to forge to the front, and then, not until Lancia had been eliminated from first place by an accident. He then had Heath to combat for first place, and it was a battle royal, which culminated at Guinea Woods. Hemery stopped for gasoline. Feverish, eager, trembling-fingered helpers poured the vital fluid into the tank. Then there was the cry, „Car coming.“ It was Heath, growing larger and larger every infinitesimal fraction of a second. The work of replenishing the tank not even completed, but quickly realizing that sufficient gasoline was there to carry him to the finish, Hemery bounded into his machine and started, his mechanic barely tumbling into his seat in time. In an instant the Darracq found her stride. But in the interim Heath had bounded up and the two were neck and neck – first one leading, then the other. They approached the Guinea Woods turn, the Darracq to the right of the road. Hemery waved his hand for Heath to give him the right of the road at the corner, but Heath knew well to give what was asked would be to that give away the race. Neck and neck, they swung around the corner at full speed. Never was there such a turn made before. Hemery swung close to the inner edge of the road, almost overturning his car. Heath swung in a wider sweep toward the outer edge, throwing up pebbles and dirt in a tremendous skid. Then came a hill about 500 yards long – and for the result of this climb read the finish: Heath 36 seconds behind Hemery.

———–

George Heath, the hero of last year’s Vanderbilt cup race, came nearly being the hero of this. Indeed, had he not been true blue, he would again have lifted the cup. When Foxhall Keene, who had been driving his Mercedes thunderer in a manner which brought him plaudits, and third place in the fifth round, and second place for part of the sixth round, met with his accident at the dangerous „S“ turn, Heath lost at least four minutes, if not more, by stopping and inquiring if Keene were hurt and if anything could be done. It was indeed a generous act worthy of the man. On only this occasion had Heath stopped his engine during the entire race. From the fourth to the seventh round, he was second in point of time to Lancia, and when Hemery displaced Lancia he see-sawed with the former until the finish. Heath drove in his usual careful, intelligent manner, and that he did not win is not due to inability in himself or his car.

————

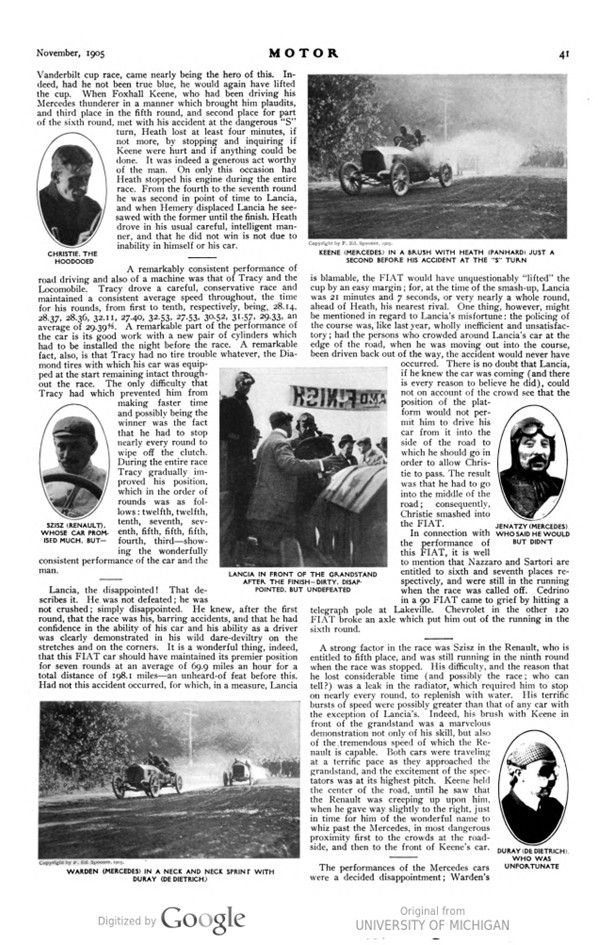

A remarkably consistent performance of road driving and also of a machine was that of Tracy and the Locomobile. Tracy drove a careful, conservative race and maintained a consistent average speed throughout, the time for his rounds, from first to tenth, respectively, being, 28.14, 28.37, 28.36, 32.11, 27.40, 32.53, 27.53, 30.52, 31.57, 29.33, an average of 29.39. A remarkable part of the performance of the car is its good work with a new pair of cylinders which had to be installed the night before the race. A remarkable fact, also, is that Tracy had no tire trouble whatever, the Diamond tires with which his car was equipped at the start remaining intact throughout the race. The only difficulty that Tracy had which prevented him from making faster time and possibly being the winner was the fact that he had to stop nearly every round to wipe off the clutch. During the entire race Tracy gradually improved his position, which in the order of rounds was as follows: twelfth, twelfth, tenth, seventh, seventh, fifth, fifth, fifth, fourth, third – showing the wonderfully consistent performance of the car and the man.

———-

Lancia, the disappointment! That describes it. He was not defeated; he was not crushed; simply disappointed. He knew, after the first round, that the race was his, barring accidents, and that he had confidence in the ability of his car and his ability as a driver was clearly demonstrated in his wild dare-deviltry on the stretches and on the corners. It is a wonderful thing, indeed, that this FIAT car should have maintained its premier position for seven rounds at an average of 69.9 miles an hour for a total distance of 198.1 miles, an unheard-of feat before this. Had not this accident occurred, for which, in a measure, Lancia is blamable, the FIAT would have unquestionably „lifted“ the cup by an easy margin; for, at the time of the smash-up, Lancia was 21 minutes and 7 seconds, or very nearly a whole round, ahead of Heath, his nearest rival. One thing, however, might be mentioned in regard to Lancia’s misfortune: the policing of the course was, like last year, wholly inefficient and unsatisfactory; had the persons who crowded around Lancia’s car at the edge of the road, when he was moving out into the course, been driven back out of the way, the accident would never have occurred. There is no doubt that Lancia, if he knew the car was coming (and there is every reason to believe he did), could not on account of the crowd see that the position of the platform would not permit him to drive his car from it into the side of the road to which he should go in order to allow Christie to pass. The result was that he had to go into the middle of the road; consequently, Christie smashed into the FIAT.

In connection with the performance of this FIAT, it is well to mention that Nazzaro and Sartori are entitled to sixth and seventh places respectively, and were still in the running when the race was called off. Cedrino in a 90 FIAT came to grief by hitting a telegraph pole at Lakeville. Chevrolet in the other 120 FIAT broke an axle which put him out of the running in the sixth round.

——-

A strong factor in the race was Szisz in the Renault, who is entitled to fifth place, and was still running in the ninth round when the race was stopped. His difficulty, and the reason that he lost considerable time (and possibly the race; who can tell?) was a leak in the radiator, which required him to stop on nearly every round, to replenish with water. His terrific bursts of speed were possibly greater than that of any car with the exception of Lancia’s. Indeed, his brush with Keene in front of the grandstand was a marvelous demonstration not only of his skill, but also of the tremendous speed of which the Renault is capable. Both cars were traveling at a terrific pace as they approached the grandstand, and the excitement of the spectators was at its highest pitch. Keene held the center of the road, until he saw that the Renault was creeping up upon him, when he gave way slightly to the right, just in time for him of the wonderful name to whiz past the Mercedes, in most dangerous proximity first to the crowds at the road- side, and then to the front of Keene’s car.

———-

The performances of the Mercedes cars were a decided disappointment, Warden’s car was the only one of the German cars to remain in the race throughout. The second round eliminated Campbell with a leaky gasoline tank. The fourth round put Jenatzy out of the running with a cracked cylinder. The sixth round brought its pall of keen disappointment to Keene, when the latter crashed into the telegraph pole at the unlucky „S“ turn. Warden was in the eighth lap when the race was called off. It was hardly expected that the last would remain throughout the entire distance, inasmuch as he had to replace two of the cylinders of his big Mercedes which had been cracked several days before the race. But Warden drove an excellent and consistent race and was always a factor to be reckoned with.

———-

The De Dietrich car was unfortunate. In the fourth round Duray lost fifteen minutes between Hyde Park and the finish, and again had trouble in the seventh round where he lost fully ten minutes. He had done so well abroad with his car that much was expected of him, and this car would undoubtedly have been a factor but for the unlucky delays.

One thing in this race stands out – „tires.“ There was less tire trouble in this big event than in the last, and far less than is the average lot of any big road race. The reason to be ascribed for this good news is not that the road surface was any better than that of last year’s course, but rather to improvement in the construction of tires. The remarkable manner in which the Diamond tires stood up under the heavy Locomobile is worthy of more than passing notice. The Michelins were, as usual, consistent, and also the Continentals on the Mercedes cars. The French Dunlop tires on the winning Darracq did remarkably well, as is shown by the result.

———-

It is being said now that France will refuse to accept the cup, as the Automobile Club of France has decided to promote no more road races, because it considers that France, being so big in the motor-car industry, deserves a larger representation in every event than any other nation. Should the cup not be accepted by France, it will be raced for in this country again, since Heath’s Panhard is also French, leaving the third, an American, as the possible defender. Whatever action France may take, there will positively be another road race in this country next year.

———-

This event, the most important road race in the world, inasmuch as America is by far the most fruitful of motor car markets, was conducted in a manner far superior to that of last year – in fact, the arrangements were perfect in all but one particular, through the single weakness of which, however, the whole affair, like the last Ormond-Daytona meet, and for the same reason, might have failed miserably. The wholly inadequate, incompetent travesty on policing was a blot i‘ the ’scutcheon and Heath’s words, while brutal and the result, no doubt, of anger and disappointment, were only too true. The writer suggested to an official before the race that perhaps the state authorities could be induced to call out a regiment, say, the „Seventh,“ and that the cost would not be greater than the need of nine hundred men to keep the crowds in order. France, Germany, Italy and England have supplied military police when necessary, and the needs was great enough on October 14. One instance where the special police (or whatever the cognomen of those individuals, who, clothed with a badge of authority, stood about like up-state hayseeds ignorant alike of races and crowds) failed signally was when, after Lancia had been stopped in front of the grandstand, Tracy in his big Loco mobile, at a mile – a – minute gait, came down the home- stretch crowded with excited, thoughtless humanity. For a moment those who saw the situation held their breaths — and then came a frantic scramble for safety and the inane shouting and curses of the „special police.“ It was not due to the particular efficiency of these travesties on the „finest“ that Tracy did not kill a few people-and him- self. Another instance was when Szisz in the Renault had the brush with Keene in front of the grandstand; the distance between the machine and the bystanders was recklessly small. It is to be hoped that the officials of subsequent races will make the policing equal to the other arrangements this year.

———–

It is to be regretted that an otherwise international road race did not bring forth British manufacturers. The Vanderbilt race has again demonstrated that the Latin peoples are still in advance of the Anglo-Saxon. Is it not time for the latter’s slower-moving intellect to come to the front now – as he will eventually? At the present moment, and judging from results, France and Italy hold the palm. Every fact brings with it the question „Why?“ Why is it that these two countries maintain the position they have won, in spite of the fact that in all other fields of industry the Anglo-Saxon makes them take a secondary position? An interesting discussion involving many points which might be of interest to motor car owner and manufacturer alike would be brought forth by a complete answer.

———-

Apropos of road racing, there has been much heard suggesting touring car races as the best way, through racing, of furthering the interests of the industry. The excellent showing in the American eliminatory trials of stock touring car models lends the necessary weight to this suggestion to demand on the part of the promoters of these events serious consideration of it. Is it not true, after all, that the buying public is rapidly „getting wise“ to the fact that the monstrosity of motor power is not for use, and that the manufacturer is „tumbling“ (particularly indicated in the new attitude of the Automobile Club of France in declining the Vanderbilt cup) to the fact that he is spending enormous sums of money with no commensurate return?