This article, written by the French journalist Paul Dumas, described the Miller 91 front wheel drive of 1924. This car was based on the idea and a request of Jimmy Murphy, who perished that year.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Motor Age, Vol. XLVI (46), No.24, December 11, 1924

Miller Front Wheel Drive Racing Car

First of New Type Was Built for the Late Jimmy Murphy – Another With Supercharger to Try for Speed Records

By PAUL DUMAS

IF WE could go through each turn on this track in 2½ seconds less than now necessary without ruining our rubber, the speed average for the 500 miles would go up at least 10 miles an hour.“ These were the words of the late Jimmy Murphy to an inquiring reporter in a conversation just prior to the last Indianapolis race.

The reporter had been timing Murphy and two other drivers and had clocked him doing slightly better than 123 miles per hour down the main stretch. He was using two stop watches and when he checked the second watch, he found that Murphy’s average speed for the 2½ -mile lap was just over 104 miles an hour. What Jimmy said about the turns was his answer to the reporter’s inquiry as to why there was so much difference between the straightaway speed and the average speed for the lap. The drop from 123 to 104 miles was easily accounted for by the time lost in negotiating the turns, of which there are four to the lap on the Indianapolis brick speedway. Figuring that these turns cause a delay of 10 seconds a lap during a 500-mile race, no less than 33 minutes are lost from the speed average that would otherwise be obtained.

Loss Less Where Banking Is Steep

What Jimmy Murphy said regarding the Indianapolis brick track holds true for any circular or oval racecourse that has been or ever will be built. The time losses in cornering are much less on the steeply banked circular board tracks due to the fact that the car is prevented from sliding off the turns by the wedging action against the tires of the outside wheels. In other words, the outside wheels are held against sliding by the angle of the track, which acts as a tapered wedge. The speeds attained on these board tracks are so high, however, that often times when cornering the rear wheels go around a portion of the turn tangential to the curvature of the course. This effect, sometimes called skidding, occurs at a different speed on each track, depending on the degree of banking and the skill of the driver.

Indianapolis Good Testing Ground

It is in reality not a real skid in that usually only the rear wheels are deflected from their true path. The skillful driver with a perfectly balanced machine can correct this effect up to a certain speed, but with the rear wheels sliding outward on the turn it requires a real driver to prevent them driving the car either to the top or the bottom of the track in defiance of all steering efforts of the front wheels. Centrifugal force produces the sliding or skidding out, but the difficulties in maneuvering out of such a position are due largely to the fact that the car is being pushed around the turn.

It is comparatively easy for the driver to place the front wheels in any position desired and it seems reasonable that if the propelling effort were produced on the front instead of the rear wheels the rear end would more or less automatically trail instead of tending to overtake the front end. The front-wheel drive idea is not a new one and its possibilities, even with a crude layout, were demonstrated years ago at Indianapolis by Barney Oldfield with his famous Christie Special.

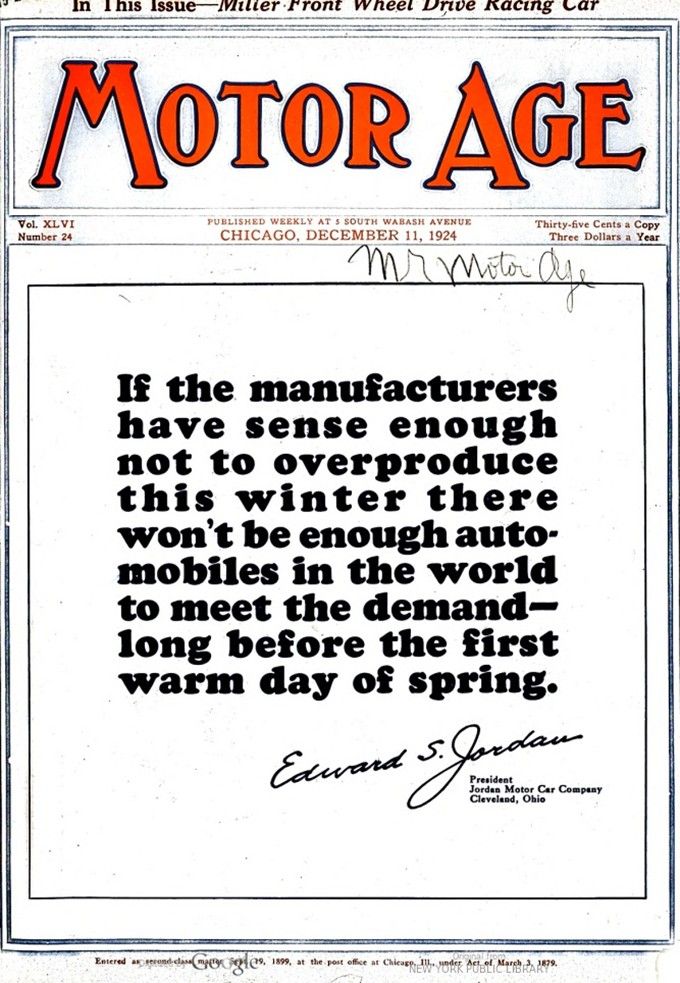

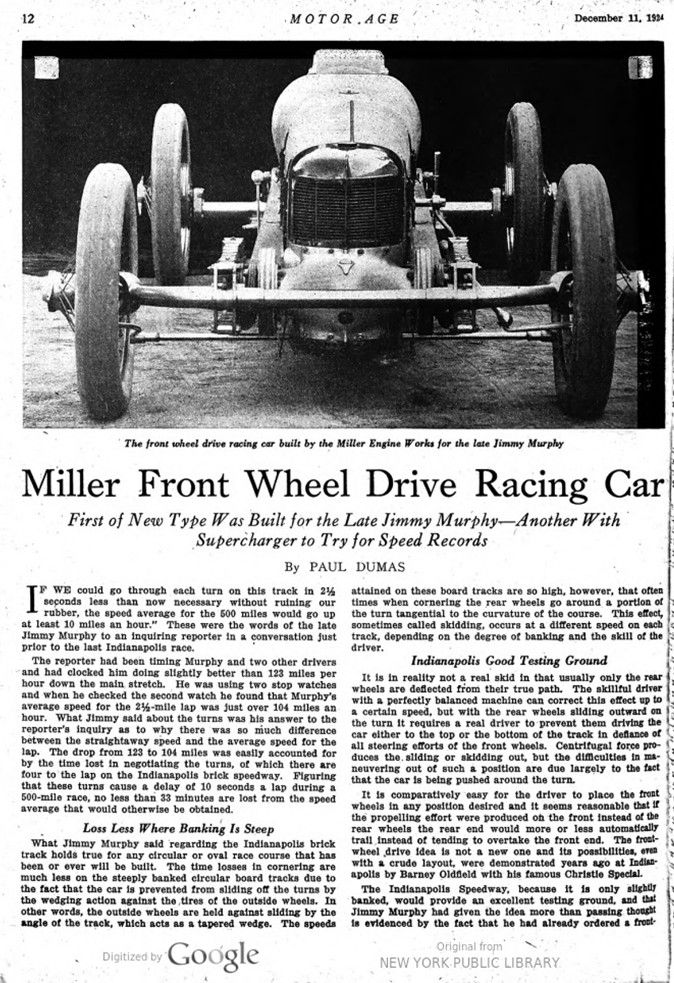

The Indianapolis Speedway, because it is only slightly banked, would provide an excellent testing ground, and that Jimmy Murphy had given the idea more than passing thought is evidenced by the fact that he had already ordered a front-drive racing car from the Miller Engine Works at Los Angeles before he was killed last summer at Syracuse. The car built at his order, which is herewith illustrated, was not ready for test until after his death and is now being held by his heirs, who are endeavoring to sell it.

The transmission details involved in the car are entirely new, so that only a summary description of the vehicle is available at this time.

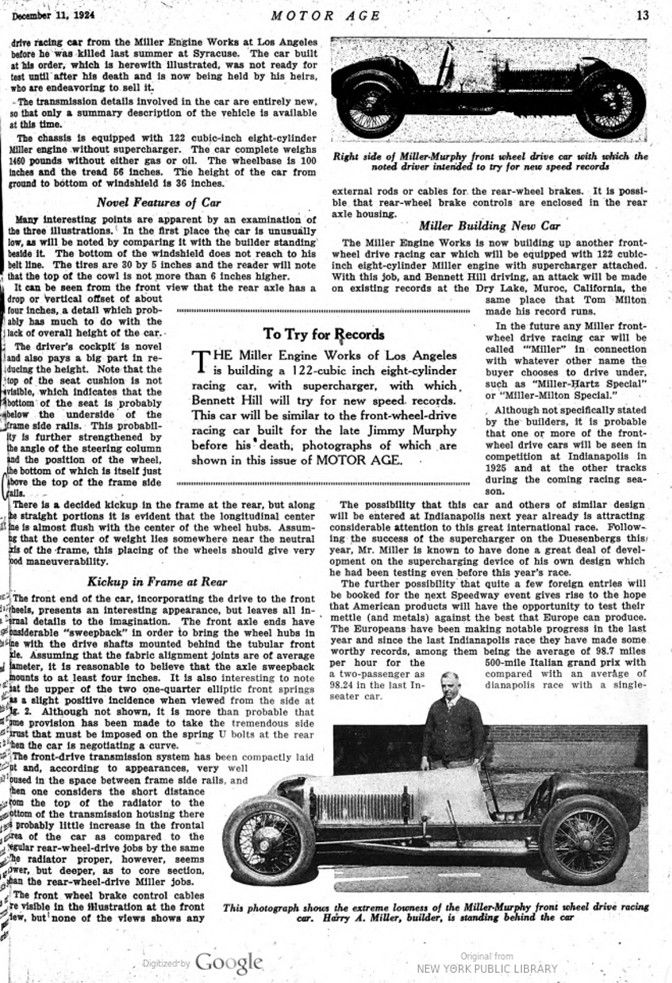

The chassis is equipped with 122 cubic-inch eight-cylinder Miller engine without supercharger. The car complete weighs 1460 pounds without either gas or oil. The wheelbase is 100 inches and the tread 56 inches. The height of the car from ground to bottom of windshield is 36 inches.

Novel Features of Car

Many interesting points are apparent by an examination of the three illustrations. In the first place the car is unusually low, as will be noted by comparing it with the builder standing beside it. The bottom of the windshield does not reach to his belt line. The tires are 30 by 5 inches, and the reader will note that the top of the cowl is not more than 6 inches higher.

It can be seen from the front view that the rear axle has a drop or vertical offset of about four inches, a detail which probably has much to do with the lack of overall height of the car. The driver’s cockpit is novel and also pays a big part in reducing the height. Note that the top of the seat cushion is not visible, which indicates that the bottom of the seat is probably below the underside of the frame side rails. This probability is further strengthened by the angle of the steering column and the position of the wheel, the bottom of which is itself just above the top of the frame side fails.

There is a decided kickup in the frame at the rear, but along the straight portions it is evident that the longitudinal centerline is almost flush with the center of the wheel hubs. Assuming that the center of weight lies somewhere near the neutral axis of the frame, this placing of the wheels should give very good maneuverability.

Kickup in Frame at Rear

The front end of the car, incorporating the drive to the front wheels, presents an interesting appearance, but leaves all internal details to the imagination. The front axle ends have considerable „sweepback“ in order to bring the wheel hubs in line with the drive shafts mounted behind the tubular front axle. Assuming that the fabric alignment joints are of average diameter, it is reasonable to believe that the axle sweepback mounts to at least four inches. It is also interesting to note that the upper of the two one-quarter elliptic front springs as a slight positive incidence when viewed from the side at fig. 2. Although not shown, it is more than probable that some provision has been made to take the tremendous side thrust that must be imposed on the spring U bolts at the rear axle when the car is negotiating a curve.

The front-drive transmission system has been compactly laid out and, according to appearances, very well housed in the space between frame side rails, and when one considers the short distance from the top of the radiator to the bottom of the transmission housing there will be probably little increase in the frontal rea of the car as compared to the regular rear-wheel-drive jobs by the same …… The radiator proper, however, seems lower, but deeper, as to core section, than the rear-wheel-drive Miller jobs.

The front wheel brake control cables are visible in the illustration at the front view, but none of the views shows any external rods or cables for. the rear-wheel brakes. It is possible that rear-wheel brake controls are enclosed in the rear axle housing.

Miller Building New Car

The Miller Engine Works is now building up another front-wheel drive racing car which will be equipped with 122 cubic-inch eight-cylinder Miller engine with supercharger attached. With this job, and Bennett Hill driving, an attack will be made on existing records at the Dry Lake, Muroc, California, the same place that Tom Milton made his record runs.

In the future any Miller front-wheel drive racing car will be called „Miller“ in connection with whatever other name the buyer chooses to drive under, such as „Miller-Hartz Special“ or „Miller-Milton Special.“

Although not specifically stated by the builders, it is probable that one or more of the front-wheel drive cars will be seen in competition at Indianapolis in 1925 and at the other tracks during the coming racing season.

The possibility that this car and others of similar design will be entered at Indianapolis next year already is attracting considerable attention to this great international race. Following the success of the supercharger on the Duesenbergs this/ year, Mr. Miller is known to have done a great deal of development on the supercharging device of his own design which he had been testing even before this year’s race. The further possibility that quite a few foreign entries will be booked for the next Speedway event gives rise to the hope that American products will have the opportunity to test their mettle (and metals) against the best that Europe can produce. The Europeans have been making notable progress in the last year and since the last Indianapolis race, they have made some worthy records, among them being the average of 98.7 miles per hour for the 500-mile Italian grand prix with a two-passenger as compared with an average of 98.24 in the last Indianapolis race with a single-seater car.

To Try for Records

THE Miller Engine Works of Los Angeles is building a 122-cubic inch eight-cylinder racing car, with supercharger, with which, Bennett Hill will try for new speed records. This car will be similar to the front-wheel-drive racing car built for the late Jimmy Murphy before his death, photographs of which are shown in this issue of MOTOR AGE.

Photo captions.

The front wheel drive racing car built by the Miller Engine Works for the late Jimmy Murphy.

Right side of Miller-Murphy front wheel drive car with which the noted driver intended to try for new speed records.

This photograph shows the exreme lowness of the Miller-Murphy front wheel drive racing car. Harry A. Miller, builder, is standing behind the car.