Text and pictures with courtesy of Hathitrust.org; compiled by motorracinghistory

The Motor World, Vol. XI, No.4, October 19, 1905; page 171 – 185

Hemery the Victor; Lancia the Lion.

How the Frenchman Quietly „Lifted the Cup“ in 276 Minutes While the Cheers Were All for the Dashing Italian – Lancia Averages 73 Miles per hour for 198 Miles – Tracy Drives a Superb and Surprising Race – Crowd Too Great for Estimate.

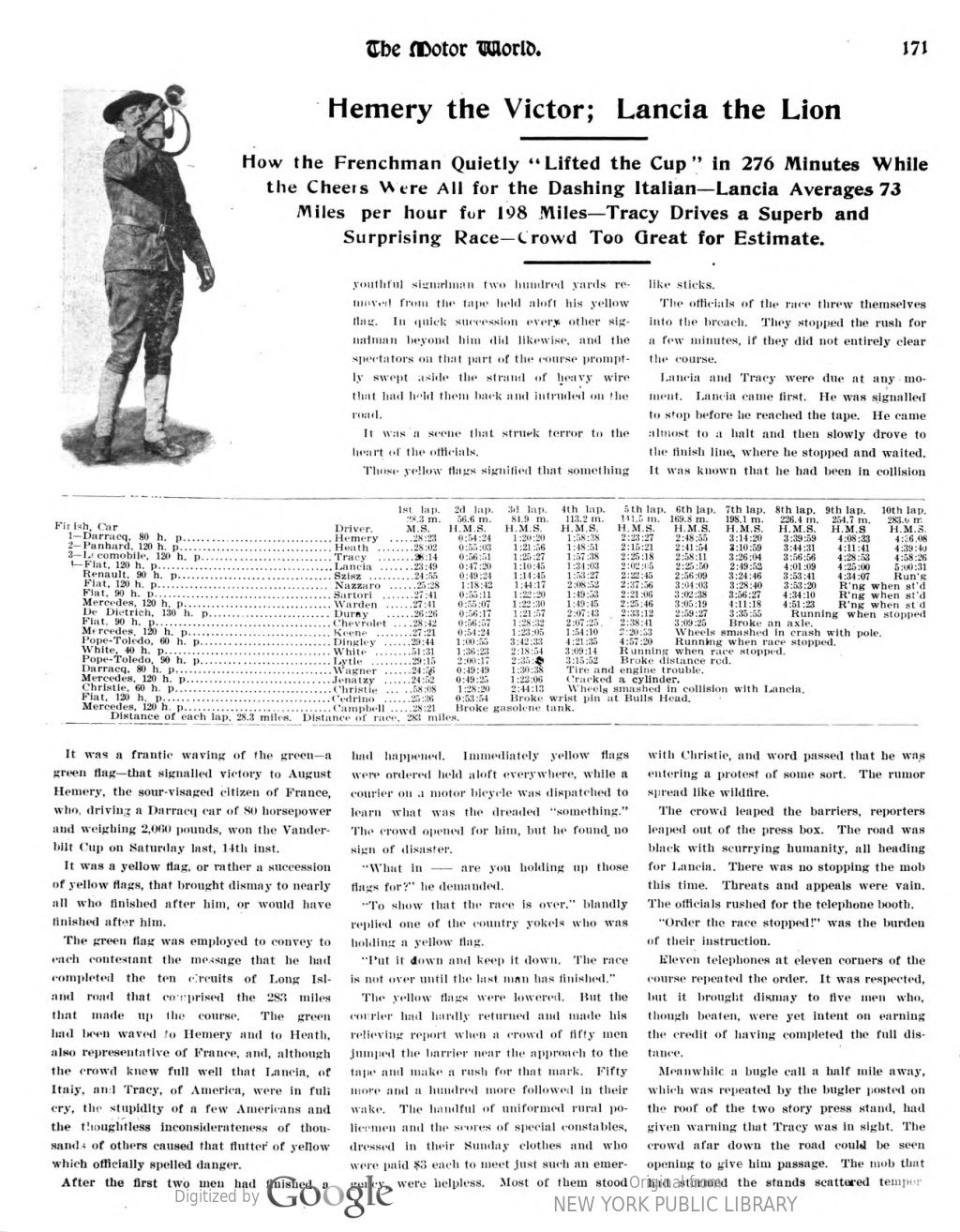

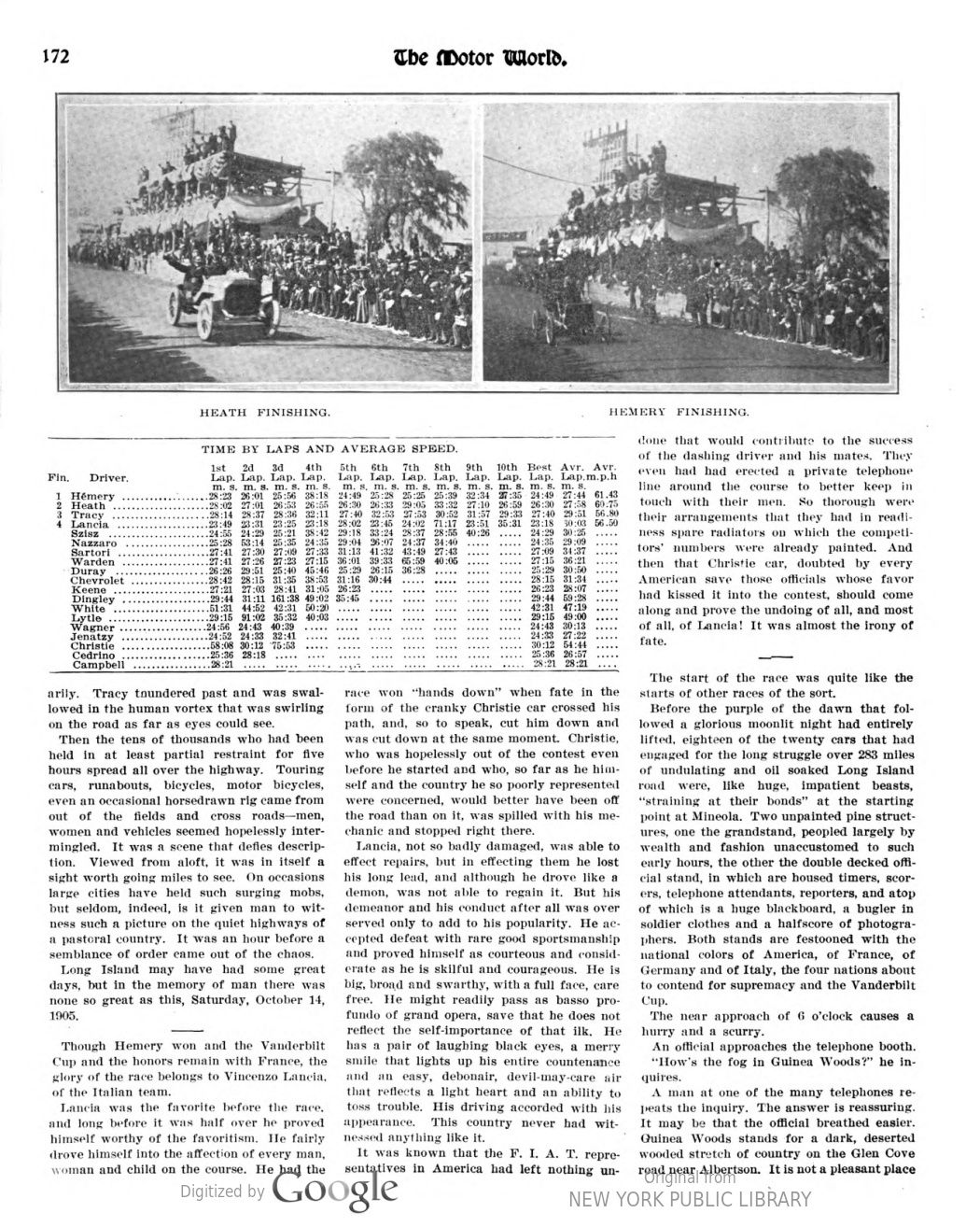

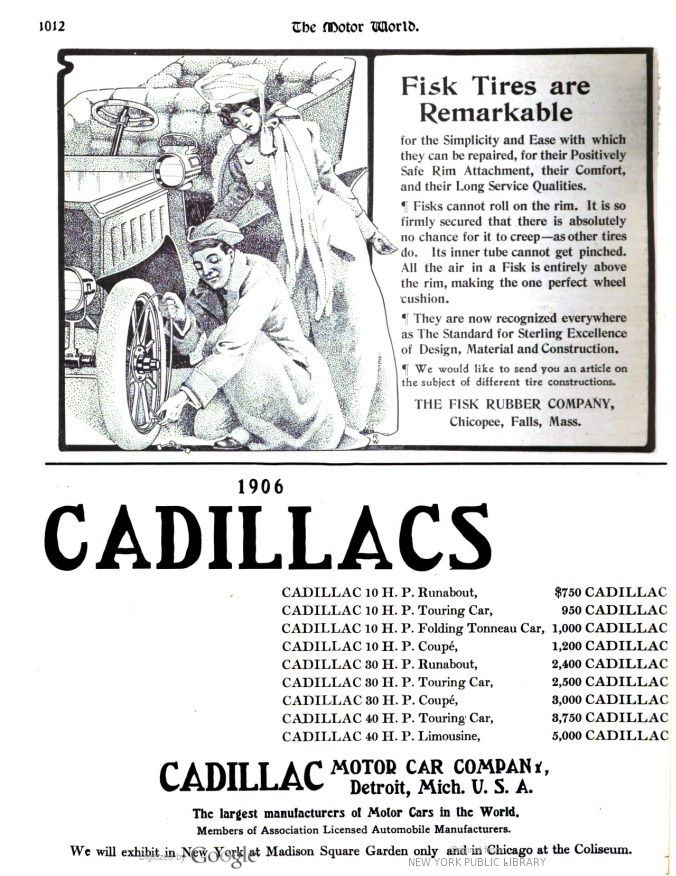

It was a frantic waving of the green – a green flag that signaled victory to August Hemery, the sour-visaged citizen of France, who, driving a Darracq car of 80 horsepower and weighing 2,060 pounds, won the Vanderbilt Cup on Saturday last, 14th inst.

It was a yellow flag, or rather a succession of yellow flags, that brought dismay to nearly all who finished after him or would have finished after him.

The green flag was employed to convey to each contestant the message that he had completed the ten circuits of Long Island road that comprised the 283 miles that made up the course. The green had been waved to Hemery and to Heath, also representative of France, and, although the crowd knew full well that Lancia, of Italy, and Tracy, of America, were in full cry, the stupidity of a few Americans and the thoughtless inconsiderateness of thousands of others caused that flutter of yellow which officially spelled danger.

After the first two men had finished a youthful signalman two hundred yards removed from the tape held aloft his yellow flag. In quick succession every other signalman beyond him did likewise, and the spectators on that part of the course promptly swept aside the strand of heavy wire that had held them back and intruded on the road.

It was a scene that struck terror to the heart of the officials.

Those yellow flags signified that something had happened. Immediately yellow flags were ordered held aloft everywhere, while a courier on a motor bicycle was dispatched to learn what was the dreaded „something.“ The crowd opened for him, but he found no sign of disaster.

„What in —— are you holding up those flags for?“ he demanded.

To show that the race is over,“ blandly replied one of the country yokels who was holding a yellow flag.

„Put it down and keep it down. The race is not over until the last man has finished.“

The yellow flags were lowered. But the courier had hardly returned and made his relieving report when a crowd of fifty men jumped the barrier near the approach to the tape and make a rush for that mark. Fifty more and a hundred more followed in their wake. The handful of uniformed rural policemen and the scores of special constables, dressed in their Sunday clothes and who were paid $3 each to meet just such an emergency, were helpless. Most of them stood like sticks.

The officials of the race threw themselves into the breach. They stopped the rush for a few minutes, if they did not entirely clear the course.

Lancia and Tracy were due at any moment. Lancia came first. He was signalled to stop before he reached the tape. He came almost to a halt and then slowly drove to the finish line, where he stopped and waited. It was known that he had been in collision with Christie, and word passed that he was entering a protest of some sort. The rumor spread like wildfire.

The crowd leaped the barriers, reporters leaped out of the press box. The road was black with scurrying humanity, all heading for Lancia. There was no stopping the mob this time. Threats and appeals were vain. The officials rushed for the telephone booth.

„Order the race stopped!“ was the burden of their instruction.

Eleven telephones at eleven corners of the course repeated the order. It was respected, but it brought dismay to five men who, though beaten, were yet intent on earning the credit of having completed the full distance.

Meanwhile a bugle call a half mile away, which was repeated by the bugler posted on the roof of the two story press stand, had given warning that Tracy was in sight. The crowd afar down the road could be seen opening to give him passage. The mob that had stormed the stands scattered temporarily. Tracy thundered past and was swallowed in the human vortex that was swirling on the road as far as eyes could see.

Then the tens of thousands who had been held in at least partial restraint for five hours spread all over the highway. Touring cars, runabouts, bicycles, motor bicycles, even an occasional horsedrawn rig came from out of the fields and crossroads – men, women and vehicles seemed hopelessly inter- mingled. It was a scene that defies description. Viewed from aloft, it was in itself a sight worth going miles to see. On occasions large cities have held such surging mobs, but seldom, indeed, is it given man to witness such a picture on the quiet highways of a pastoral country. It was an hour before a semblance of order came out of the chaos.

Long Island may have had some great days, but in the memory of man there was none so great as this, Saturday, October 14, 1905.

—-

Though Hemery won and the Vanderbilt Cup and the honors remain with France, the glory of the race belongs to Vincenzo Lancia, of the Italian team.

Lancia was the favorite before the race. and long before it was half over, he proved himself worthy of the favoritism. He fairly drove himself into the affection of every man, woman and child on the course. He had the race won „hands down“ when fate in the form of the cranky Christie car crossed his path, and, so to speak, cut him down and was cut down at the same moment. Christie, who was hopelessly out of the contest even before he started and who, so far as he himself and the country he so poorly represented were concerned, would better have been off the road than on it, was spilled with his mechanic and stopped right there.

Lancia, not so badly damaged, was able to effect repairs, but in effecting them he lost his long lead, and although he drove like a demon, was not able to regain it. But his demeanor and his conduct after all was over served only to add to his popularity. He accepted defeat with rare good sportsmanship and proved himself as courteous and considerate as he is skillful and courageous. He is big, broad and swarthy, with a full face, carefree. He might readily pass as basso profundo of grand opera, save that he does not reflect the self-importance of that ilk. He has a pair of laughing black eyes, a merry smile that lights up his entire countenance and an easy, debonair, devil-may-care air that reflects a light heart and an ability to toss trouble. His driving accorded with his appearance. This country never had witnessed anything like it.

It was known that the F.I.A.T. representatives in America had left nothing undone that would contribute to the success of the dashing driver and his mates. They even had had erected a private telephone line around the course to better keep in touch with their men. So thorough were their arrangements that they had in readiness spare radiators on which the competitors‘ numbers were already painted. And then that Christie car, doubted by every American save those officials whose favor had kissed it into the contest, should come along and prove the undoing of all, and most of all, of Lancia! It was almost the irony of fate.

—-

The start of the race was quite like the starts of other races of the sort.

Before the purple of the dawn that followed a glorious moonlit night had entirely lifted, eighteen of the twenty cars that had engaged for the long struggle over 283 miles of undulating and oil-soaked Long Island Road were, like huge, impatient beasts, „straining at their bonds“ at the starting point at Mineola. Two unpainted pine structures, one the grandstand, peopled largely by wealth and fashion unaccustomed to such early hours, the other the double decked official stand, in which are housed timers, scorers, telephone attendants, reporters, and atop of which is a huge blackboard, a bugler in soldier clothes and a halfscore of photographers. Both stands are festooned with the national colors of America, of France, of Germany and of Italy, the four nations about to contend for supremacy and the Vanderbilt Cup.

The near approach of 6 o’clock causes a hurry and a scurry.

An official approaches the telephone booth.

„How’s the fog in Guinea Woods?“ he inquires.

A man at one of the many telephones repeats the inquiry. The answer is reassuring. It may be that the official breathed easier. Guinea Woods stands for a dark, deserted wooded stretch of country on the Glen Cove Road near Albertson. It is not a pleasant place in which to encounter a fog at any time. The man with the big megaphone shouts far-carried messages designed to clear the course of men and cars that have no business there. Other men with broad bands of ribbon on their arms – the officials – and others with badges on their chests and obviously countrymen – the special constables, seek also to relieve the congestion. They have not entirely succeeded, when a man in what is plainly a brand-new suit of russet leather – the starter – and another in corduroy – the clerk – become all animation. There is a plentitude of shouted orders. Then a hooded individual with a high cheeked face, like a Mongolian, and a funny corkscrew beard of auburn hue, who had been walking around it, eyeing it critically, climbs into the big white car bearing the No. 1. He is Jenatzy, the Belgian, representing Germany, who is to drive the German car owned and nominated by an American of wealth-Robert Graves. Graves is on the spot, and exchanges a few words with Jenatzy, as does W. K. Vanderbilt, Jr., the donor of the cup and the referee of the race. Vanderbilt is wearing his familiar black satin coat, and beneath it a gray sweater, the better to keep out the early morning chill.

The starter tolls off the minutes, then the seconds:

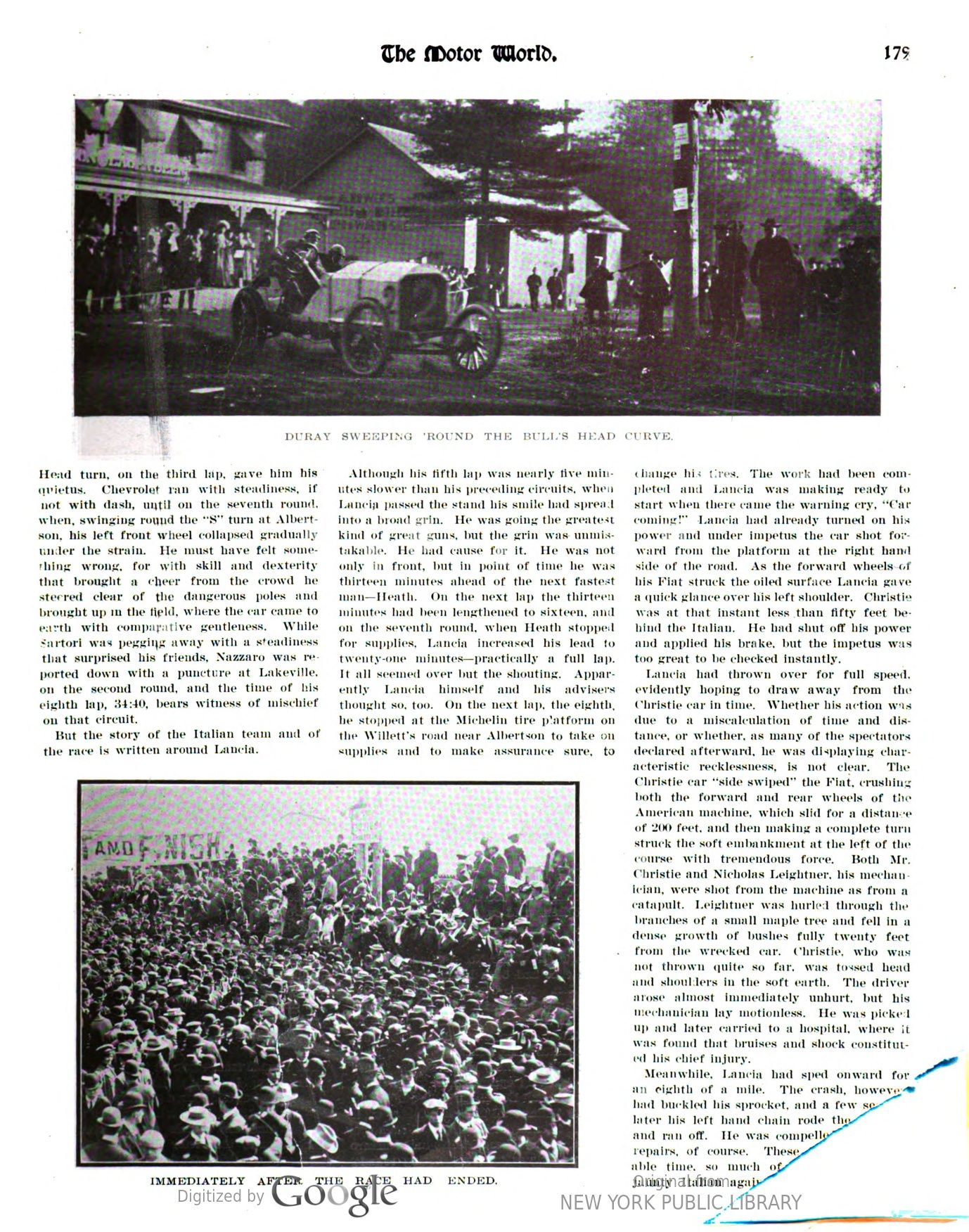

„Three! Two! One!“ – Mrs. Vanderbilt, in a box overlooking the scene, animatedly beats time in unison with the starter’s count — then a pump handle motion of the arm, a shrieked „Go!“, a big puff of smoke, a fairly hearty cheer and Jenatzy slips easily away and is lost in the distance even before the sixty seconds have elapsed when „Go“ is shouted into the ear of Duray in the big blue De Dietrich. Dingley, attired in khaki and driving the „little“ Pope-Toledo-the 50 horsepower car that won the American eliminating trial – is No. 3. A really hearty cheer rewards him as he starts. It was his only cheer. Silence was his portion when next he passed.

No. 4 – ah! Lancia, the dashing, smiling Lancia. If he is concerned or nervous ever so slightly there is no sign of it. There is no smoke pouring from his car. It is thundering and belching fire, but the flame is blue and bright, but, strange to say, one tongue of it actually is licking his left front tire. It seems odd that this should be the case, but Lancia, he must know and must have weighed the chances. Keene, Wagner, Tracy – looking like a wax figure, so pale is he, and with an orange hued kerchief about his neck -Tracy who had cracked a cylinder only the day before and who had worked the live-long night that he might be here – Nazzaro, Warden – another victim of cracked cylinders – Szisz, and then No. 11 – Christie – but Christie is missing, yet scarcely is missed so quickly do the minutes fly.

Cedrino, another swarthy citizen of Italy, he is there; so is his wife. She is nervous, very. She pinches her lower lip. She makes to speak to her husband, but he is off and away before she can edge close to him. Campbell, with an X on his radiator to dodge the superstition saturated No. 13-Heath, who waves a goodbye – Lytle, Chevrolet – then another break. No. 17, Clarence Grey Dismore’s German entry, which failed to reach these shores-Hemery, White, Sartori – they are all away.

—–

The spectators settle back. Some of the officials speak in half whispers of Christie’s absentation. He has sent no message of explanation. None knows where he is not even the bearded „Jimmy“ Breeze, who is supposed to own the Christie car and, in whose name, it was nominated. Breese is on the spot, wearing a badge and a buttonaire and other indications that he had surveyed himself full in the mirror despite the early morning hour. There is talk that eleventh hour family objections had prevailed, and that Christie has flunked. There also are some stronger expressions-much stronger ones. The man puts his megaphone to his lips, and Christie is forgotten.

„No. 1 has passed Willetts Avenue,“ he announces.

It is the first of very many messages that the splendid telephone service delivered and that kept the spectators so well informed throughout the whole forenoon. It was a busy forenoon for the megaphone man. He earned every cent of his fee.

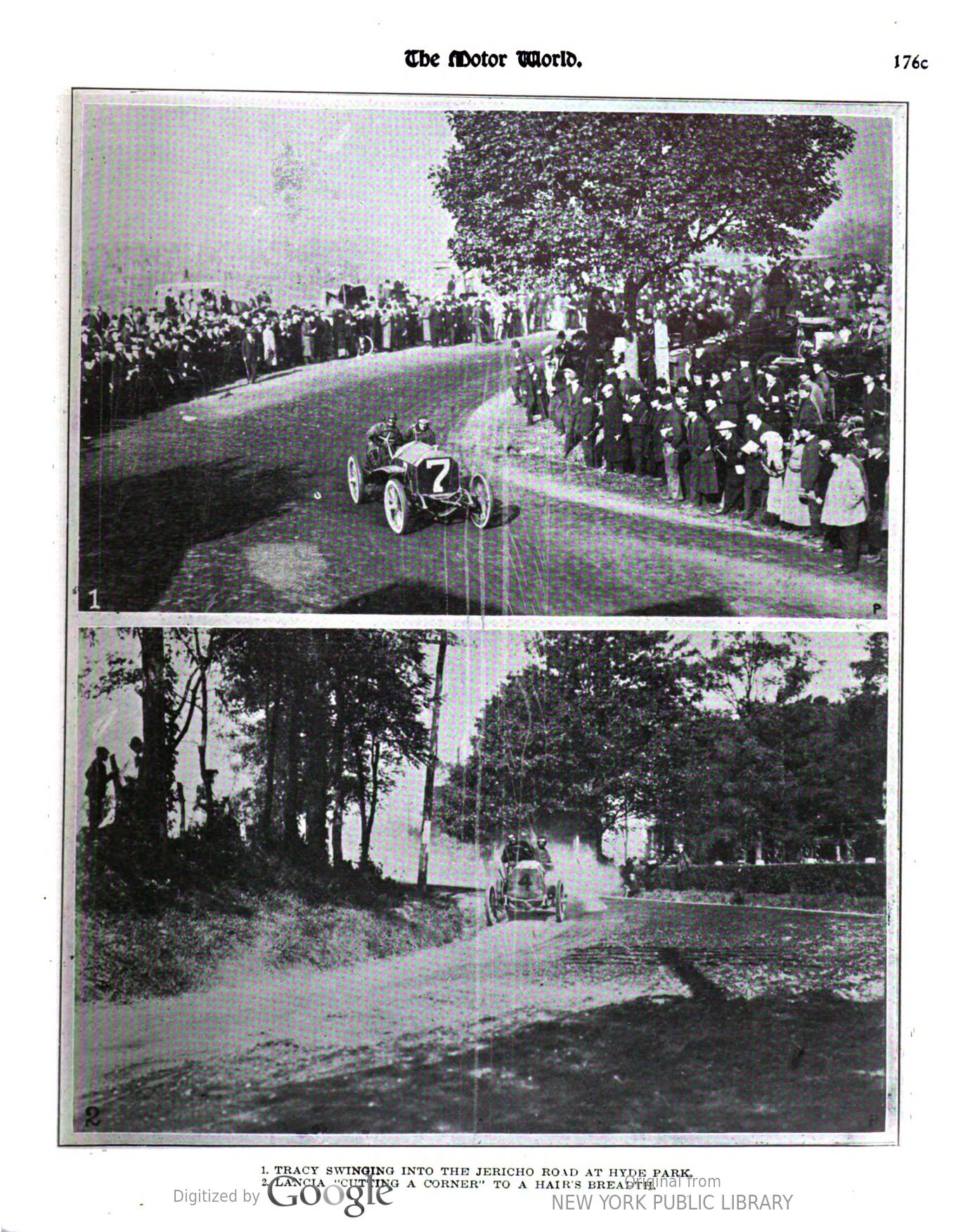

The sun has dissipated the slight morning mist. The sky is fleckless blue. It is a glorious day – one of those rare days in October. Already is the chill of early morning well removed. „Society,“ in the cars and the stand, has removed or is removing her expensive furs or other wraps; it reveals equally expensive morning toilets. Common democracy, not in cars and not on the stand, is removing top coats and sweaters. The bugle blows a-down the road. The call is echoed by the bugle outlined against the sky atop the press stand. … „Car coming!“ .. It is Jenatzy. He tears past at a terrific pace. Again, the bugle. Again, the echo. . . A wave of comment sweeps the crowd. It is No. 4. No. 4 is Lancia. Already he has passed Duray and Dingley, two of the three men who were in front of him. He has made big gains in the first twenty-eight miles…… He hurls by like a thunderbolt. He knows that he has done good work, for his face is wreathed in smiles. The crowd, too, knows it without awaiting the megaphone announcement. It cheers – cheers heartily. Lancia hears it. His smile appears to widen and he waves his hand. The megaphone gives out that Lancia’s time for the 28.3 miles is 23:49, and again that wave of admiration stirs the multitude. It is sustained speed such as Americans have never witnessed since their nation first established a highway; and these roads are not the best that America now holds. Seventy-one miles per hour! It is speed that staggers belief…. Keene thunders by … Mrs. Vanderbilt leans far over the rail and follows him with her eyes until he is a mere speck in the distance … Keene is of the „Vanderbilt set,“ you know … But the little lady in white with a green feather stuck in her hat assumes so many attitudes during the forenoon and holds some of them so long that there is ground for suspicion that she likes the click of the cameras cen- tred on her, or poses merely because she fancies posing is becoming….

At 6:38 comes the cry „Here’s Christie!“ and, sure enough, it is the forgotten and derelict American. His low hung car is sounding its deep, sonorous rattatoo, but there are false notes – missed notes – discernible. He approaches slowly and makes as if to stop. „Jimmy“ Breese is all excitement. Referee Vanderbilt seems to share it. Before Christie halts, and although a moving start is contrary to the rules, the referee runs out into the centre of the road and waves him on. Christie goes; but not fast enough to excite comment and with not one hand of encouragement. His engine appears to labor. There is a report that it also had suffered in the epidemic of cracked cylinders …. It is nearly an hour before the Breese with whiskers sets eyes on his car again. Few others take notice of its passing.

——

The story of the first passing of the cars as seen from the official stand is practically the story of each successive period marked by that point.

On the second lap Jenatzy was still in front, but Lancia was pulling him down rapidly. The Italian had gained 63 seconds on the German in the first lap, and he gained 62 seconds on the next round, although Jenatzy had quickened his pace some 20 seconds, Lancia did the two rounds in 23:49 and 23:31, respectively; Jenatzy in 24:52 and 24:33. Lancia had come to America with a great reputation. He was living up to it, and the spectators were not slow to realize the fact. They warmed up to him quickly, and at the end of another lap they had eyes and interest only for him. All others were practically lost sight of.

It was „all Lancia.“

He passed Jenatzy on the third approach to Bull’s Head – which is the right-angled turn near Wheatley Station – but he never let up. He kept crowding the pace, which reached its climax on the fourth round, which was negotiated in 23:18, or seventy-three miles an hour. That was the fastest lap of the race, and of the nineteen contenders Lancia alone got under 24 minutes; and he did so no less than six times. Szisz, in the beetle shaped Renault, did 24:29, which was the next best performance. For seven laps, or 198 miles, when accident befell him, the Italian averaged 69.9 miles an hour.

Is it any wonder that, though he failed to lift the cup, his glory is so great?

Apart from the hurricane speed that was so terrific as to stagger comprehension, the grandstand received its first real thrill on the second lap. An instant before Wagner (Darracq), moving at a pace of sixty-eight miles an hour, crossed the line, his right rear tire exploded with a tremendous report. Whole sections of his inner tube flew high into the air and were picked up fifty yards apart. The explosion brought the dense and curious crowd beyond the barrier onto the road, and the officials watching his flight shuddered at the prospect. But Wagner was equal to the emergency. He wavered from his course scarcely a hair’s breadth, the crowd parted, and when he had slackened pace he threw up one hand as if to let the officials know that he had full control of the car and that all was well.

„Fine work, that,“ commented one of them. And it was fine work.

It was but a few minutes later that the officials had a scare of which the spectators knew nothing. Word came over the telephone of an accident on the Willetts road.

None knew what it was, and no particulars were forthcoming. The operator was seek- ing information in rather a loud voice.

„Easy, there, easy-speak softly,“ cautioned the alert associate referee, A. R. Pardington.

His caution proved wise on an occasion when rumors were travelling fast and assum- ing exaggerated form in no time at all. Word soon came that the accident, whatever it was, had been righted.

—–

It was a bad day for the American team. Christie had started a full lap behind and was not a serious factor; White, on the first round, had „run into the barn at Bull’s Head“ the report became frequent during the forenoon-for water or something else and was also out of the reckoning; Lytle had smashed into a big dog near Mineola, on the second round, and buckled his distance rod and stood no show, and on the third round there remained only Tracy, in the Locomobile, and Dingley, in the „little“ Pope-Toledo, as it was generally termed.

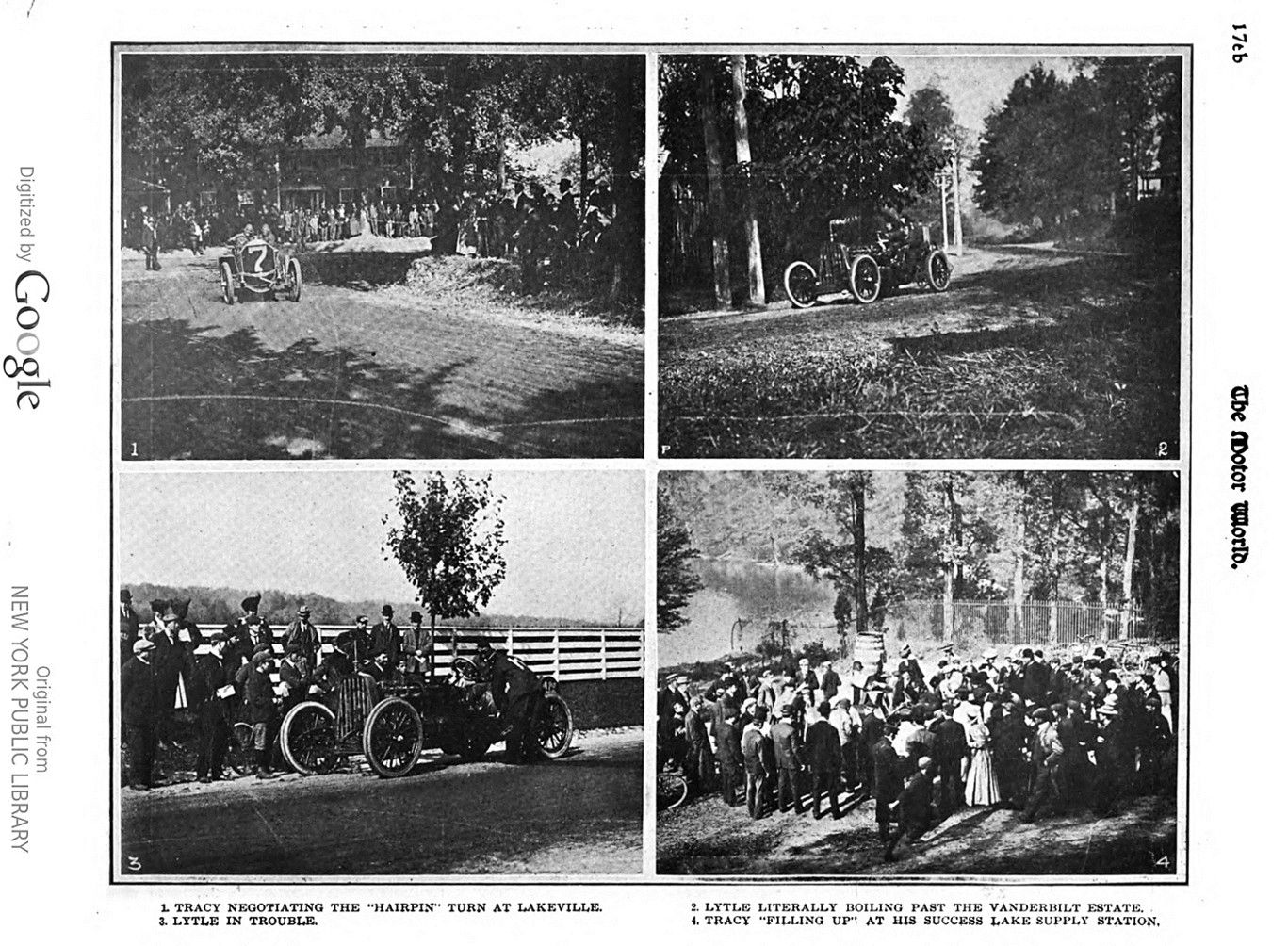

Word came on the third round that they had passed Hyde Park together, and the American public then saw a running fight between their sole remaining „hopes.“ After a fashion, they „had it out“ all the way up the Jericho turnpike. Passing the grand-stand Dingley was leading by thirty yards. Tracy seemed cautious about attempting to pass, and they passed out of sight in this order at a pace which all could see was not comparable with that of the foreigners. It was nearly two hours before Dingley was seen again. An inlet valve broke and, dropping into the cylinder, played havoc with it. He was announced as out of the race, but by heroic work a repair was effected and Dingley restarted with the hope of finishing „no matter how.“ He kept going until the contest was ordered stopped.

After striking the dog at Mineola Lytle discovered the buckled distance rod, but believing it to be strong enough to hold together he proceeded slowly on his low gear. The accident had thrown his wheels out of whack. In the Guinea Woods, on the Glen Cove road, one of them began acting so dangerously that his chauffeur, Tattersall, was dispatched afoot to find a substitute.

This gave rise to a series of the most conflicting rumors it is possible to conceive. Without awaiting the return of Tattersall Lytle elected to „take chances.“

„Lytle has dropped his mechanic and is driving alone,“ was the first report that came over the telephone.

„Lytle does not know where he lost his man, but says the fall won’t hurt him, as he is a football player.“ „Lytle is lost; his man is driving the car.“ „Lytle’s man landed on his head in the ditch.“ „Lytle’s man is reported lying in a ditch in the Guinea Woods.“ „Lytle’s chauffeur broke his neck.“

These and other alarming reports of the sort were received in response to every ef- fort to obtain definite information. Finally Referee Vanderbilt and a physician hurried away in Mr. Vanderbilt’s own racing car. They were absent some time, but when they returned „nobody hurt“ was announced. All the while Tattersall, about whose supposed death all were so greatly concerned, was footing it lackadaisically along the roadside. Lytle picked up another man, and after changing wheels covered one fairly fast lap and a rather slow one, each time passing the stand with a plume of steam flying from his radiator chimney and with water spouting from it like a fountain, his chauffeur making frantic efforts to protect himself from the hot fluid that was dashed into his face at every pound.

—–

The behavior of White, the only American to suffer much tire trouble – he shed two tires – was past understanding. He made a holiday of the race. He went „into the barn at Bull’s Head“ regularly each lap – apparently for water, but as the door of the barn was closed in the faces of the curious none can say with certainty that these excursions were for water. At about the time he had been forgotten would come the report, „White is going again“; then he would alternately speed and loiter over the course, only to again dis- appear in the barn. Although about 140 miles behind the leader, he was still mean- dering toward the barn when the crowd stampeded and forced the stoppage of the race. His performance was one of the bitterest disappointments of the day.

There was once that White varied the monotony of „going into the barn at Bull’s Head.“ It was on his fourth lap – it is necessary to emphasize the „his“ – that for a change he literally „took to the woods.“ in rounding the Guinea Woods turn on the Glen Cove Road he miscalculated his speed and to avoid striking a telegraph pole he ran full into the bushes and undergrowth and then emerged on the other side of the pole. White’s ill luck pursued him every foot of the way. On one of his very many stop- pages he borrowed a bicycle to go to the fa- mous barn for some needed part, and en route even the chain of the bicycle broke.

Christie, the fifth member of the American team, stood no earthly show at any stage. Its performance after the substitution of his cranky car after its failure in the elimination trials amply justified all the hard things that were said of the car and of the Cup Commissioners, who threw out the Thomas racer that the Christie might compete in the cup race itself. Christie’s family strenuously objected to his driving, he himself tried to beg off, and he even developed rheumatism and carried his arm in a sling. At the eleventh hour a cylinder is supposed to have cracked, and it would have redounded to the credit of America, if not to himself, had he never repaired it. Before he and Lancia collided he had torn off a tire, of course, and at Bull’s Head he stalled his engine. The crowd there gave him a hand, and, after he had been pushed off, the car waltzed all over the road. It would have been a mercy had he and White run into some barn and locked the door so tightly that they could not get out again that day.

—–

Lytle’s damaged distance rod held together until on the fifth round, when, with the strained steering socket, it gave way near Lakeville. He, of course, lost control of the car, and, with few to see it, it spectacularly ran off the road, demolished a rail fence and charged into a potato patch. There it halted, right side up and with no injury done save to the fence.

Tracy, the one remaining hope of America, ran like a clock. He stopped only to replenish supplies and to scrape a slippery clutch. Otherwise, as the figures by laps serve to show, he ran steadily and surely, if not spectacularly and meteorically. The statistics show that the men who finished one, two, three were the steady goers. Tracy finished third by virtue of his steadiness. Few of those who saw him perform and place the Stars and Stripes higher even than most men had dared hope knew the odds under which he had labored. The day before he had cracked a cylinder and done some other dam- age. Word was quickly sent to the Locomobile factory at Bridgeport. There was no train due, so the needed parts were loaded into a Locomobile touring car and rushed to Long Island. It was midnight before the damage was remedied; it was after midnight before the car was weighed in; it was 4 o’clock Saturday morning before the engine was turned over. It worked at the first turn, but there was no chance for „tuning up“- no chance for a „try out.“ It all adds to the wonder that Tracy and his car performed so grandly, so greatly to the glory of America. After the fourth lap his countrymen awoke to the merit of the splendid work he was doing, and thereafter cheered him heartily.

If the American team was all but eliminated, so, too, was the Italian team, while the German representation was completely wiped out. True, Nazzaro and Sartori, of Italy, and Warden, for, if not of Germany, were still circling the course when the race was ordered stopped, but so, too, were White and Dingley of America, but all were from twenty-eight to fifty or more miles behind the leaders and stood no earthly show „Herr“ Campbell, who fell heir to No, 13 after „Herr“ Keene had wailed so loudly that it was removed from him, was the very first man to be bowled out. As salve for his superstitiousness Campbell was permitted to display an X instead of the figure 13, but it did not save him. On the second round a hole was punched in his gasolene tank, and that was the end of him.

On the third lap Jenatzy, chief hope of the German team, and Warden were reported stopped at Bull’s Head. Both got going again, but on the very next lap, at the same place, Jenatzy went down and out with a cracked cylinder. Warden then had more than his share of tire trouble. One tire went flat and compelled a stop at Lakeville. Then another flew off in the Guinea Woods, and the wealthy American who was playing Ger- man for the day went on without it. It was replaced, but another one was lost at Hyde Park, and Warden limped by the grandstand far to the side of the road, bumping on one rim. Keene, though successful in escaping No. 13, did not escape accident, and came close to serious injury. He was performing well, when on the sixth lap he sought to negotiate the „S“ turn at Albertson. There are several so-called „S“ turns, but this one is rightly so styled. „Ticklish“ enough at best, there are three telegraph poles set not fifty feet apart in the very belly of the „S.“ The mer swung to the right entering the „S and to the left in leaving it. The three poles are all on the left side of the rond.

When Keene, too confident or slightly misjudging his speed, swung to the right, his car skidded straight for the first pole. He saw his danger and quickly shifted his steering wheel. His chauffeur, nearest the pole, saw the danger, too, and, half rising, leanel fa. over Keene to avoid the impact. He avoided it, but the left front wheel of the car struck the pole with such force that the chauffeur was pitched headlong out of it, and, strangely enough, fell directly in front of the right rear wheel, which partly passed over his chest. The front wheel was wrecked and the axle bent, but Keene kept his seat. iffeur was stunned and lay where he fell, partly under the car, but happily he was not seriously injured. Heath was trang Keene, and, seeing the accident, brought up quickly to avoid running over the prostrate man. He stopped on his high gear, which stalled his engine and lost him some valuable moments before he could again get going.

Heath, the American representing France, was afterward credited with great gallantry and self-sacrifice – even at the cost of the trophy – in stopping to lend assistance to the American thus disabled while in the service of Germany, but he was quick to repudiate the credit.

„I stopped solely to avoid running over Mr. Keene’s chauffeur,“ a Motor World man heard him disclaim. „There were two hundred other men on the spot to render assist-ance, if assistance was needed.“

After his car had been pushed off the road Keene, wearing a rather shabby gray over- coat, made his way to the grandstand, where he remained until the end of the race. He told his story to the Vanderbilts and the Belmonts and to a perfectly lovely man wearing an English hunting costume topped by a pancake hat with a green ribbon band. He remained standing directly under the Vanderbilt box for an hour or so. Several times he wiped his watery eyes with a handkerchief. Some of those who fancy that all is tears that flows from the eye saw that Keene was weeping for disappointment.Of the Italians, Cedrino was the first to be bowled out. A broken wristpin at the Bull’s Head turn, on the third lap, gave him his quietus. Chevrolet ran with steadiness, if not with dash, until on the seventh round. when, swinging round the „S“ turn at Albertson, his left front wheel collapsed gradually under the strain. He must have felt something wrong, for with skill and dexterity that brought a cheer from the crowd he steered clear of the dangerous poles and brought up in the field, where the car came to earth with comparative gentleness. While Sartori was pegging away with a steadiness that surprised his friends, Nazzaro was reported down with a puncture at Lakeville, on the second round, and the time of his eighth lap, 34:40, bears witness of mischief on that circuit.

But the story of the Italian team and of the race is written around Lancia.

Although his fifth lap was nearly five minutes slower than his preceding circuits, when Lancia passed the stand his smile had spread into a broad grin. He was going the greatest kind of great guns, but the grin was unmistakable. He had cause for it. He was not only in front, but in point of time he was thirteen minutes ahead of the next fastest man-Heath. On the next lap the thirteen minutes had been lengthened to sixteen, and on the seventh round, when Heath stopped for supplies, Lancia increased his lead to twenty-one minutes – practically a full lap. It all seemed over but the shouting. Appar- ently Lancia himself and his advisers thought so, too. On the next lap, the eighth, he stopped at the Michelin tire platform on the Willett’s road near Albertson to take on supplies and to make assurance sure, to change his tires. The work had been completed and Lancia was making ready to start when there came the warning cry, „Car coming!“ Lancia had already turned on his power and under impetus the car shot forward from the platform at the right hand side of the road. As the forward wheels of his Fiat struck the oiled surface Lancia gave a quick glance over his left shoulder. Christie was at that instant less than fifty feet behind the Italian. He had shut off his power and applied his brake, but the impetus was too great to be checked instantly.

Lancia had thrown over for full speed. evidently hoping to draw away from the Christie car in time. Whether his action was due to a miscalculation of time and dis- tance, or whether, as many of the spectators declared afterward, he was displaying characteristic recklessness, is not clear. The Christie car „side swiped“ the Fiat, crushing both the forward and rear wheels of the American machine, which slid for a distance of 200 feet, and then making a complete turn struck the soft embankment at the left of the course with tremendous force. Both Mr. Christie and Nicholas Leightner, his mechanician, were shot from the machine as from a catapult. Leightner was hurled through the branches of a small maple tree and fell in a dense growth of bushes fully twenty feet from the wrecked car. Christie, who was not thrown quite so far. was tossed head and shoulders in the soft earth. The driver arose almost immediately unhurt, but his mechanician lay motionless. He was picked up and later carried to a hospital, where it was found that bruises and shock constituted his chief injury.

Meanwhile, Lancia had sped onward for an eighth of a mile. The crash, however, had buckled his sprocket, and a few seconds later his left hand chain rode the sprocket and ran off. He was compelled to stop for repairs, of course. These took time – valuable time, so much of it, that when the jaunty Italian again got going he was no longer the leader. He had been nearly half an hour ahead. He was now nearly half au hour behind. He drove with the recklessness and dash born of desperation.

While all this was happening, the tens of thousands, possibly the hundred thousand, congregated on or in the vicinity of the grandstand, were wondering what had be- .come of their dashing hero. They knew that something had happened, but there was no telephone at the point where the accident occurred and information was not easy to obtain. Referee Vanderbilt himself came over to the telephone booth and inquired.

„Where’s Lancia?“ It was some time before the query was answered.

„No. 4 has burst a tire at Lakeville,“ the megaphone announced.

A great buzz of sympathy swept the large crowd.

How the report arose is not known, but it was succeeded by one even more dumbfounding:

„Lancia is out.“

The crowd was aghast. Few even knew was the second man, now that the pop- had fallen. They were still wondering when there came word of ene station at Willetts, Both cars are dis- abled, but no one is hurt,“ is the way the announcement ran.

There were some strong things said about Christie, his car and every one connected with them.

Then, and not until then, it was that the spectators who had not been „keeping tabs“ awoke to the realization that there was such a man as Hemery in the race. They were amazed to find that he had crawled past Heath, and, with Lancia out, had a safe lead in the short distance to go.

But Lancia was not out. The man with the megaphone said so.

„No. 4 has passed Lakeville,“ he announced.

All knew for whom No. 4 stood. It was the first that had been heard of him since the collision. None even suspected that he was again in the fight. When the truth dawned on them, a mighty shout went up — the mightiest of the whole day. When but a few minutes later Lancia, no longer smiling, but with a deadly earnest face, dashed past at lightning speed, there was another acclaiming roar. But Hemery, Heath, Tracy, Szisz and Nazzaro all had passed him while he chafed in enforced idleness, and each was now a long way ahead. Szisz and Nazzaro fell on evil times in those closing rounds, however, and though in the final lap all was not well with Lancia himself – he had to again stop to have tires and chain readjusted-he passed those two and pushed ahead of Tracy also.

When he halted at the grandstand he supposed that he had beaten the American also. But there had been three minutes difference in the times of their starts, and while Lancia waited, with the stampeded crowd surrounding him, Tracy came with a roar long before three minutes had expired. He beat the Italian for third place by two minutes and five seconds.

There was no smile on Lancia’s face. The lower lip had dropped and it seemed as if the big, brave son of Italy might blubber were he much provoked. The bitter in his cup of sweet had come to the top. The man with the megaphone had to climb into Lancia’s car and shout loudly that a path might be cleared for him that he might reach the weighing station at Albertson.

—–

The French team repeated its performance of last year. It again secured first and sec- ond places, but this time a genuine blown-in- the-bottle Frenchman won and not the make believe American article of the previous race. Heath, the victor in 1904, was the runner-up on this occasion. Hemery and Heath finished in front by virtue of consistent performance. They kept going all the time. Their stops were few and short. On the fourth lap and again on the ninth Hemery had tire trouble, while Heath had his portion on the eighth round. Both were careful drivers, and Heath especially took no chances on the turns. Hemery rarely looked up, but it was Heath’s practice to salute the grand stand on almost every occasion. His wife was there. Perhaps that’s the reason. Once passing the stand Hemery’s chauffeur lost his goggles, and until the eighth lap this was absolutely the only incident that served to draw attention to them. It was only those who were keeping close record of the times who realized that Hemery was likely to have a „look in.“ At the end of the fourth lap Heath, Warden, Sartori, Szisz, Keene, Tracy and Lancia, of course, were leading him easily, but in the next round he began to move up. Some of them fell on evil times, and he passed Warden and Tracy, moving from eighth to sixth place. On the next lap he went by all save Lancia and Heath.

Then on the momentous eighth lap Lancia had his accident and Heath also had some minor trouble, and the sulky Frenchman in the black sweater, with „Darracq“ spelled across his chest, went to the front and stayed there, though small woes delayed him on the last circuit and enabled Heath to cut down his lead from nearly five minutes to a scant 36 seconds. When they finished both men were acclaimed, but rather mildly. The crowd seemed too absorbed to cheer real lustily or in accord. Not one of the finishers -not even Tracy – received what may rightly be termed a real hearty cheer.

Wagner, Hemery’s running mate, was in hard luck. On the second lap one of his French Dunlop tires exploded-the Darracq Company had some difference with the Michelin house abroad and changed their tire equipment at the eleventh hour – and on the third, when near Albertson, he lost his gear case, the grease was thrown out, and in no time at all the overheated gears locked fast and Wagner’s long trip across the Atlantic was set at naught.

Szisz, in the Renault, did some really remarkable work. His first three laps averaged faster than all the others save Lancia, and on the fifth round he gave the grand-stand a taste of his real speed. He and Keene came down the long, straight stretch together, „Herr“ Keene in front, but with the Frenchman footing faster and gaining with every bound. Keene held the centre of the road, but almost in front of the stand the little red car swung sharply to the left, scattering dirt over the officials. For fifty yards they raced side by side; then the little red car fairly leaped in front of the big white one and drew away with every revolution. But Szisz had had his troubles and was doomed to have more of them. His cooling system had become deranged and time and again he was forced to stop and cool his engine and replenish his water supply, and twice, according to reports, to extinguish fire. How he ever did so well in the face of such difficulties is remarkable. Four of the five Frenchmen were running when the race was called off, Duray, in the big blue Dietrich, being the remaining survivor, who, though troubled, was „still in the ring.“

——

It may well be supposed that after winning such a race the victor would be brim- ming over with good nature, and there are those who claim to have seen Hemery all agrin and with an overjoyed retinue of Frenchmen kissing the grime off his face. But certainly when he appeared at the Albertson to „weigh out“ he exhibited some of the sour surliness that his face reflects. When he dismounted he was given a glass of stimulant. Then seeing a score of cameras levelled at him he made an angry rush at them, while one of his following actually did strike the photographer of Collier’s Weekly.

When they dismounted from the Panhard, Heath and his mechanician were all a tremble; if anything, the man was worse off than the master, and seemed sadly in need of the drink and raw eggs that were quickly handed him.

When he came on the scene Lancia had recovered his smile, and after shaking hands with Heath coolly took out a cigarette and puffed it as unconcernedly as if he had just returned from a pleasure jaunt miles instead of a punishing driv 300 miles, most of it covered than any living man eve eled on unrailed earth.

Only Razzio’s average of 64.8 miles per hour in the 311 miles race for the Florio Cup, in Italy, is comparable with Lancia’s flight of the first 198 miles in the first 170 minutes of Saturday’s race.

While at Albertson Lancia heard the story started by some idiot that he purposely had fouled Christie to put him out of the running. That he had no earthly reason to endanger his own life and his own chances, particularly with such driftwood as the Christie car, was patent; but the report greatly exercised the Italian, and later he took a touring car and drove to the Christie quarters to set himself right and to inquire solicitously about the injured chauffeur.

Heath rather bitterly denounced the inconsiderate crowd that not only intruded on the 10ad but stood in the zones of danger at the corners and kept the drivers‘ nerves on edge.

When Tracy, obviously very tired, appeared at the scales he was cheered in a fashion by the crowd gathered there that made his drawn face light up; and the crowd did not overlook A. L. Riker, the man who designed and superintended the building of ocomobile that Tracy drove so well and the first American car to finish well up in a speed contest with the best that Europe holds. Riker was also one of the official weighmasters, and the cheer given him caused the big fellow to blush like a school girl.

Some Things Happen to Hemery.

Hemery’s good fortune ended with the race on Saturday.

On Sunday, while his car was being viewed by a number of spectators, one of them, after lighting a cigar, threw the unextinguished match on the oil soaked ground outside the garage. A blaze instantly followed. The car was somewhat damaged in its more vulnerable parts, not not enough to affect its operation, as it was in use the following day.

On Monday the surly young Frenchman learned that he could do no more racing for a full year. On that day the cable brought word that for insolence to the officials during the recent Florio Cup race in Italy he had been suspended for twelve months by the Automobile Club of Italy. On Tuesday the cable added that the Automobile Club of France would recognize and respect the action of the Italian organization.

Hemery, who is in no danger of ever becoming popular wherever he may go, is thus barred from all the big events of 1906.

When asked of what his insolence had consisted, he blithely stated that he had bluntly requested the Italian officials to go to hell – a blatherskite expression or desire which he repeated several times over.

—–

The foreign drivers are not strong on receptions — a fact which is not difficult of understanding after one has encountered most of them. Pounding anvils or handling trowels would seem more in their lines. The Automobile Club of America, however, tendered them a reception on Monday night, and exactly three of them attended – Heath, a man of means, Duray and Tracy.

On Wednesday afternoon a professional promoter „tendered“ them a dinner in the New York Press Club’s aerial restaurant, at which only Szisz, Lancia and Nazaro put in an appearance. There were present, however, a score of newspaper men and others who had received invitations to come and pay $5 each, and several of them made speeches. The omnipresent Winthrop E. Scarritt was there, of course, and for a change read a poem. The most interesting things were said by Lancia and A. R. Pardington. Lancia said he appreciated the cordiality of his treatment and promised to tell „his King“ about it. Pardington said that the Long Island authorities had already ten- dered the use of the course for a race next year.

—–

Nearly all of the members of the French and Italian teams will sail for home today. Before leaving, Lancia and Nazzaro made a flying trip to view Niagara Falls.