The magazine Automobile Topics was known for their very extended reports, combined with ample illustrations; so this one on the first Indianapolis 500-mile race. Very extended and very informative, specially for race interested. I’ve divided the entire article in three sections: part 1 Introduction, part 2 How the Race was Run and part 3 discussing most contestants and race specifics. Nontheless, each of the three parts is a whole lot of information. Enjoy reading here the first part.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

AUTOMOBILE TOPICS. Vol. XXII, No. 9, June 3, 1911

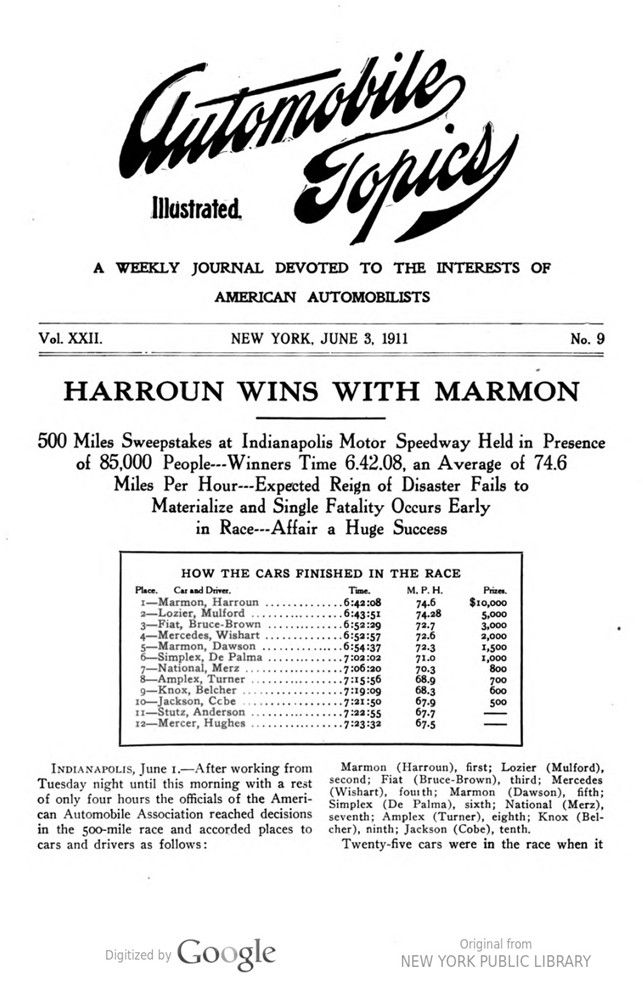

HARROUN WINS WITH MARMON

500 Miles Sweepstakes at Indianapolis Motor Speedway Held in Presence of 85,000 People —

Winners Time 6.42.08, an Average of 74.6 Miles Per Hour —

Expected Reign of Disaster Fails to Materialize and Single Fatality Occurs Early in Race —

Affair a Huge Success

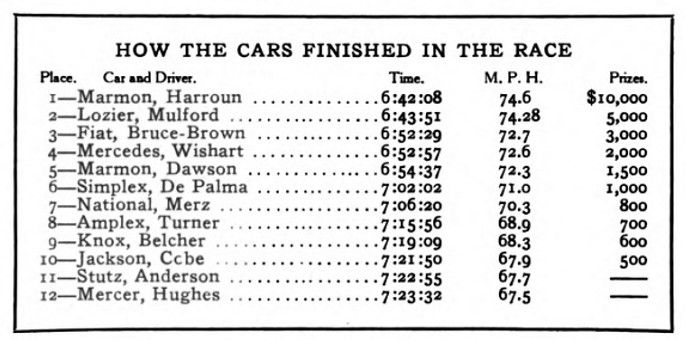

INDIANAPOLIS, June 1. — After working from Tuesday night until this morning with a rest of only four hours the officials of the American Automobile Association reached decisions in the 500-mile race and accorded places to cars and drivers as follows: 0 Marmon (Harroun), first; Lozier (Mulford), second; Fiat (Bruce-Brown), third; Mercedes (Wishart), fourth; Marmon (Dawson), fifth Simplex (De Palma), sixth; National (Merz), seventh; Amplex (Turner), eighth; Knox (Belcher), ninth; Jackson (Cobe), tenth.

Twenty-five cars were in the race when it was called after the twelfth car finished. Following is the order in which they stood:

13—Firestone-Columbus, Frayer.

14—Inter-State, H. Endicott.

15—Pope-Hartford, Fox.

16—Fiat, Hearne.

17—National, Wilcox.

18—McFarlan, Adams.

19—Cutting, Delaney.

20—Mercer, Bigelow.

21—Simplex, Beardsley.

22—Velie, Hall.

23—Cole, W. Endicott.

24—Benz, Burman.

25—Benz, Knipper.

The consolation winners were Gil Anderson, in Stutz car No. 10, who finished eleventh, and Hughie Hughes, in Mercer No. 36, who finished twelfth. In the semi-official scores given out at the finish of the race Lee Frayer, in a Firestone-Columbus car, got credit for being in eleventh place. The readjustment showed that Frayer did not finish in one of the twelve leading cars. The corrected time showed that Ray Harroun won the race in 6:42:08 instead of 6:41 :08, an average speed of 74.6 miles an hour. Mulford was 1:43 behind the leader, according to the revised figures. Only twenty-eight seconds were between Bruce- Brown and Wishart, who trailed ten minutes behind Harroun.

——-

INDIANAPOLIS, May 30. — This vast inland town is just witnessing the closing scenes of the biggest jamboree in its history. It has just “pulled off the greatest sporting event in the annals of this country, has taken into its capacious and hospitable bosom scores of thousands of visitors, fed them, housed them, dispatched them to its Brobdingnagian speedway, presented to their entranced eyes the spectacle of an almost flawless speed carnival, and is now welcoming them as they return and speeding them on their varied ways. And in the four days beginning with Sunday, May 28. and to end tomorrow, May 31, automobile racing history of the ultra-modern kind has been written eloquently and enduringly.

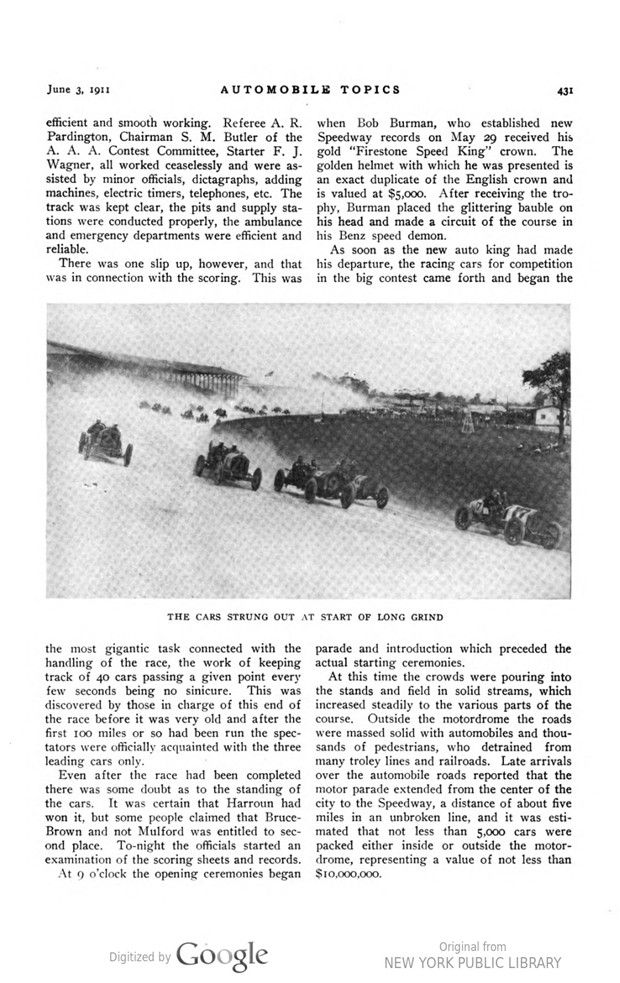

Superlatives almost fail when one attempts to describe the race itself — the great 500 miles sweepstakes which constituted the sole event of the season’s opening at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. It was a contest of the Homeric kind — in which giants of the wheel matched skill against skill, brain against brain and daring and courage against like precious qualities. For nearly seven hours they circled the brick paved speedway, measuring exactly 2½ miles, to the cheers of 85,000 people who lined the immense oval, filling stand after stand, and parkings spaces by the score, and overflowing into the field by thousands, a goodly number of whom flocked to the danger spots — the steeply banked turns leading into the straights. First one and then another shot to the front and had his brief time of triumph; only to be displaced on account of temporary retirement for supply replenishment or tire replacement. As the field of 4o cars dwindled, although not as rapidly as was expected — some of the favorites dropped out — such as Bragg, Grant, Tetzlaff and Disbrow; but the majority of the fancied ones hung on tenaciously and strove and battled for the lead.

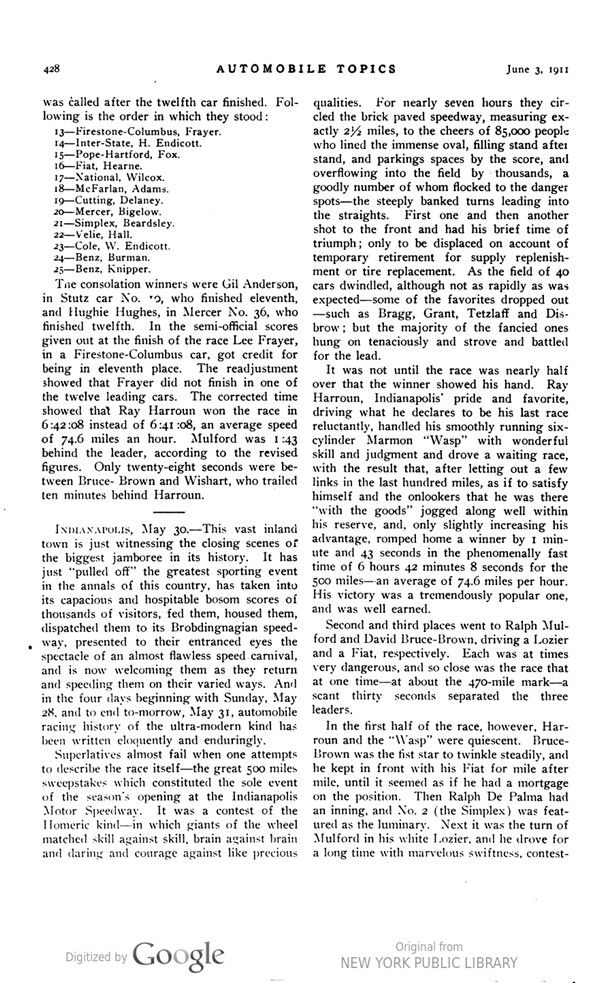

It was not until the race was nearly half over that the winner showed his hand. Ray Harroun, Indianapolis‘ pride and favorite, driving what he declares to be his last race reluctantly, handled his smoothly running six-cylinder Marmon “Wasp” with wonderful skill and judgment and drove a waiting race, with the result that, after letting out a few links in the last hundred miles, as if to satisfy himself and the onlookers that he was there “with the goods” jogged along well within his reserve, and, only slightly increasing his advantage, romped home a winner by 1 minute and 43 seconds in the phenomenally fast time of 6 hours 42 minutes 8 seconds for the 500 miles — an average of 74.6 miles per hour. His victory was a tremendously popular one and was well earned.

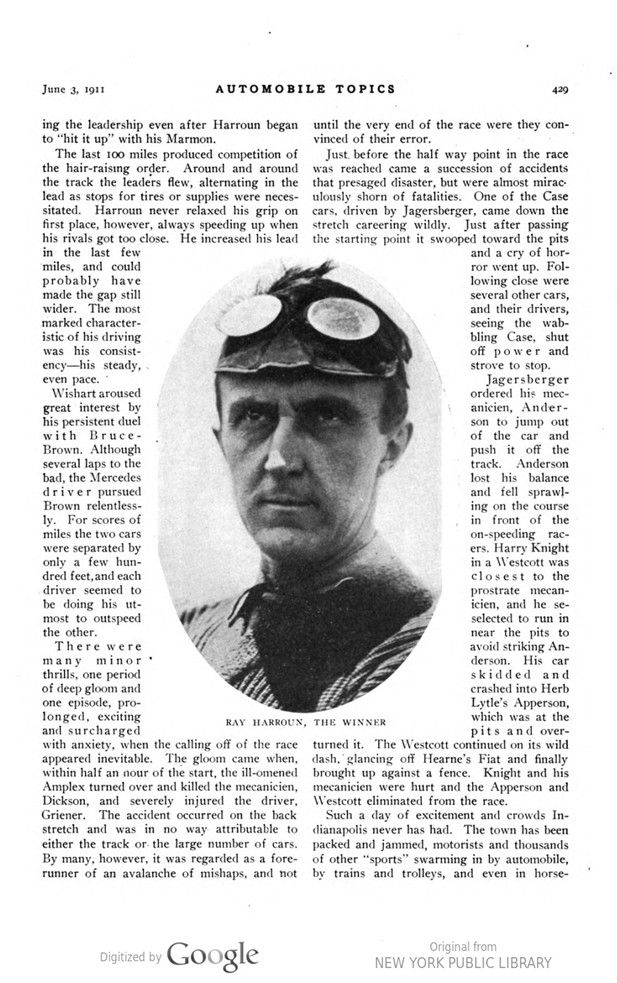

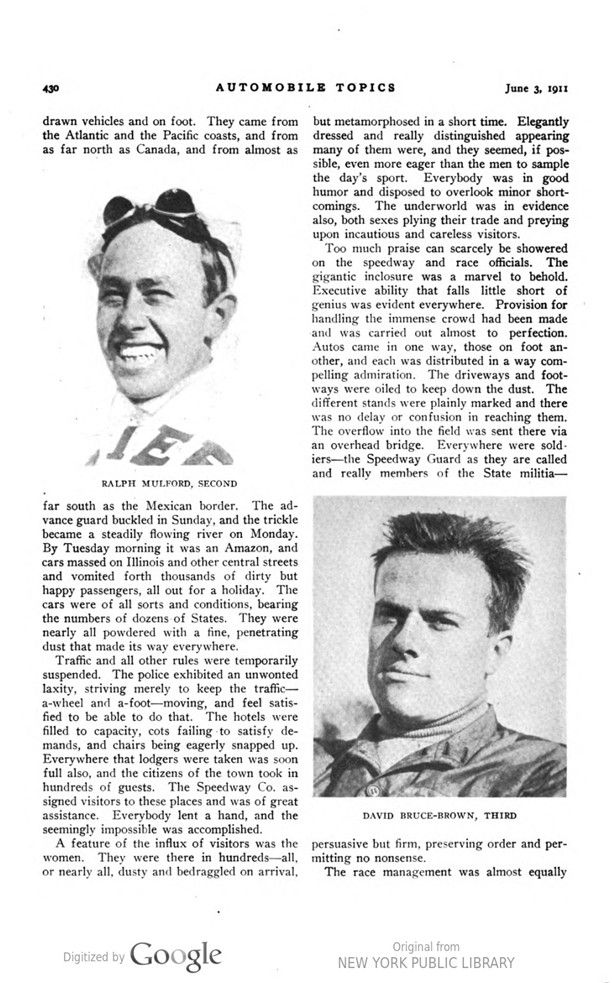

Second and third places went to Ralph Mulford and David Bruce-Brown, driving a Lozier and a Fiat, respectively. Each was at times very dangerous, and so close was the race that at one time — at about the 470-mile mark — a scant thirty seconds separated the three leaders.

In the first half of the race, however, Harroun and the „Wasp” were quiescent. Bruce-Brown was the fist star to twinkle steadily, and he kept in front with his Fiat for mile after mile, until it seemed as if he had a mortgage on the position. Then Ralph De Palma had an inning, and No. 2 (the Simplex) was featured as the luminary. Next it was the turn of Mulford in his white Lozier, and he drove for a long time with marvelous swiftness, contesting the leadership even after Harroun began to “hit it up” with his Marmon.

The last 100 miles produced competition of the hair-raising order. Around and around the track the leaders flew, alternating in the lead as stops for tires or supplies were necessitated. Harroun never relaxed his grip on first place, however, always speeding up when his rivals got too close. He increased his lead in the last few miles and could probably have made the gap still wider. The most marked characteristic of his driving was his consistency — his steady, even pace.

Wishart aroused great interest by his persistent duel with Bruce-Brown. Although several laps to the bad, the Mercedes driver pursued Brown relentlessly. For scores of miles the two cars were separated by only a few hundred feet, and each driver seemed to be doing his utmost to outspeed the other.

There were many minor thrills, one period of deep gloom and one episode, prolonged, exciting and surcharged with anxiety, when the calling off of the race appeared inevitable. The gloom came when, within half an hour of the start, the ill-omened Amplex turned over and killed the mechanician, Dickson, and severely injured the driver, Griener. The accident occurred on the back stretch and was in no way attributable to either the track or the large number of cars. By many, however, it was regarded as a forerunner of an avalanche of mishaps, and not until the very end of the race were they convinced of their error.

Just before the halfway point in the race was reached came a succession of accidents that presaged disaster, but were almost miraculously shorn of fatalities. One of the Case cars, driven by Jaegersberger, came down the stretch careering wildly. Just after passing the starting point, it swooped toward the pits and a cry of horror went up. Following close were several other cars, and their drivers, seeing the wabbling Case, shut off power and strove to stop.

Jaegersberger ordered his mechanician, Anderson to jump out of the car and push it off the track. Anderson lost his balance and fell sprawling on the course, in front of the on-speeding racers. Harry Knight in a Westcott was closest to the prostrate mechanician, and he selected to run in near the pits to avoid striking Anderson. His car skidded and crashed into Herb Lytle’s Apperson, which was at the pits and overturned it. The Westc0tt continued on its wild dash, glancing oft Hearne’s Fiat and finally brought up against a fence. Knight and his mechanician were hurt and the Apperson and Westcott eliminated from the race.

Such a day of excitement and crowds Indianapolis never has had. The town has been packed and jammed, motorists and thousands of other “sports” swarming in by automobile, by trains and trolleys, and even in horse-drawn vehicles and on foot. They came from the Atlantic and the Pacific coasts, and from as far north as Canada, and from almost as far south as the Mexican border. The advance guard buckled in Sunday, and the trickle became a steadily flowing river on Monday. By Tuesday morning it was an Amazon, and cars massed on Illinois and other central streets and vomited forth thousands of dirty but happy passengers, all out for a holiday. The cars were of all sorts and conditions, bearing the numbers of dozens of States. They were nearly all powdered with a fine, penetrating dust that made its way everywhere.

Traffic and all other rules were temporarily suspended. The police exhibited an unwonted laxity, striving merely to keep the traffic —- a-wheel and a-foot -— moving, and feel satisfied to be able to do that. The hotels were filled to capacity, costs failing to satisfy demands, and chairs being eagerly snapped up. Everywhere that lodgers were taken was soon full also, and the citizens of the town took in hundreds of guests. The Speedway Co. assigned visitors to these places and was of great assistance. Everybody lent a hand, and the seemingly impossible was accomplished.

A feature of the influx of visitors was the women. They were there in hundreds – all or nearly all, dusty and bedraggled on arrival, but metamorphosed in a short time. Elegantly dressed and really distinguished appearing many of them were, and they seemed, if possible, even more eager than the men to sample the day’s sport. Everybody was in good humor and disposed to overlook minor shortcomings. The underworld was in evidence also, both sexes plying their trade and preying upon incautious and careless visitors.

Too much praise can scarcely be showered on the speedway and race officials. The gigantic inclosure was a marvel to behold. Executive ability that falls little short of genius was evident everywhere. Provision for handling the immense crowd had been made and was carried out almost to perfection. Autos came in one way, those on foot another, and each was distributed in a way compelling admiration. The driveways and footways were oiled to keep down the dust. The different stands were plainly marked and there was no delay or confusion in reaching them. The overflow into the field was sent there via an overhead bridge. Everywhere were soldiers — the Speedway Guard as they are called and really members of the State militia —persuasive but firm, preserving order and permitting no nonsense.

The race management was almost equally efficient and smooth working. Referee A. R. Pardington, Chairman S. M. Butler of the A. A. A. Contest Committee, Starter F. J. Wagner, all worked ceaselessly and were assisted by minor officials, dictagraphs, adding machines, electric timers, telephones, etc. The track was kept clear, the pits and supply stations were conducted properly, the ambulance and emergency departments were efficient and reliable.

There was one slip up, however, and that was in connection with the scoring. This was the most gigantic task connected with the handling of the race, the work of keeping track of 40 cars passing a given point every few seconds being no sinecure. This was discovered by those in charge of this end of the race before it was very old and after the first IOO miles or so had been run the spectators were officially acquainted with the three leading cars only.

Even after the race had been completed there was some doubt as to the standing of the cars. It was certain that Harroun had won it, but some people claimed that Bruce-Brown and not Mulford was entitled to second place. To-night the officials started an examination of the scoring sheets and records.

At 9 o’clock the opening ceremonies began when Bob Burman, who established new Speedway records on May 29 received his gold “Firestone Speed King” crown. The golden helmet with which he was presented is an exact duplicate of the English crown and is valued at $5,000. After receiving the trophy, Burman placed the glittering bauble on his head and made a circuit of the course in his Benz speed demon.

As soon as the new auto king had made his departure, the racing cars for competition in the big contest came forth and began the parade and introduction which preceded the actual starting ceremonies.

At this time the crowds were pouring into the stands and field in solid streams, which increased steadily to the various parts of the course. Outside the motordrome the roads were massed solid with automobiles and thou- sands of pedestrians, who detrained from many trolley lines and railroads. Late arrivals over the automobile roads reported that the motor parade extended from the center of the city to the Speedway, a distance of about five miles in an unbroken line, and it was estimated that not less than 5,000 cars were packed either inside or outside the motordrome, representing a value of not less than $10,000,000.

Photo captions.

RAY HARROUN, THE WINNER

RALPH MULFORD, SECOND

DAVID BRUCE—BROWN, THIRD

THE CARS STRUNG OUT AT START OF LONG GRIND