The June 1913 issue of The Automobile gives several articles, of which this is the pivotal one as it deals with 500-Mile Race, not only discussing the course of the race by e.g. the several century marks. It also concerns with technical issues and the way different pit crews were working. Indeed, a long read but you’ll never be dissapointed.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

The AUTOMOBILE – Vol. XXVIII, No. 23 Chicago, June 5, 1913

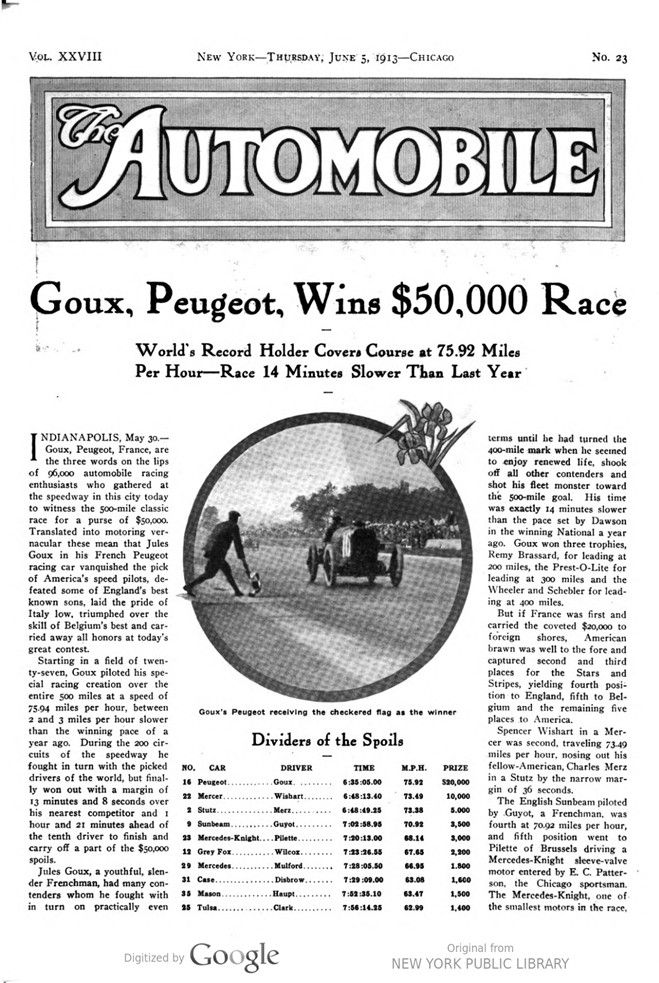

Goux, Peugeot, Wins $50,000 Race

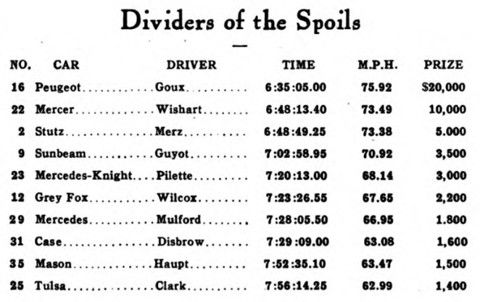

World’s Record Holder Covers Course at 75.92 Miles Per Hour – Race 14 Minutes Slower Than Last Year

INDIANAPOLIS, May 30. – Goux, Peugeot, France, are the three words on the lips of 96,000 automobile racing enthusiasts who gathered at the speedway in this city today to witness the 500-mile classic race for a purse of $50,000. Translated into motoring vernacular these mean that Jules Goux in his French Peugeot racing car vanquished the pick of America’s speed pilots, defeated some of England’s best known sons, laid the pride of Italy low, triumphed over the skill of Belgium’s best and carried away all honors at today’s great contest.

Starting in a field of twenty-seven, Goux piloted his special racing creation over the entire 500 miles at a speed of 75.94 miles per hour, between 2 and 3 miles per hour slower than the winning pace of a year ago. During the 200 circuits of the speedway he fought in turn with the picked drivers of the world, but finally won out with a margin of 13 minutes and 8 seconds over his nearest competitor and 1 hour and 21 minutes ahead of the tenth driver to finish and carry off a part of the $50,000 spoils.

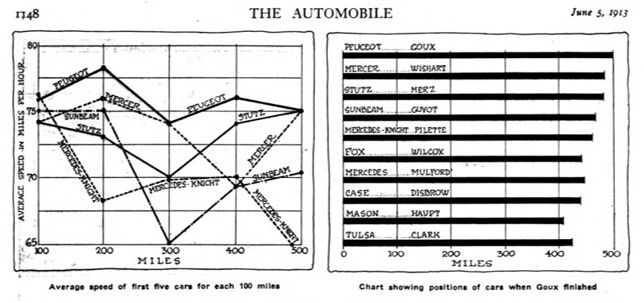

Jules Goux, a youthful, slender Frenchman, had many contenders whom he fought with in turn on practically even terms until he had turned the 400-mile mark when he seemed to enjoy renewed life, shook off all other contenders and shot his fleet monster toward the 500-mile goal. His time was exactly 14 minutes slower than the pace set by Dawson in the winning National a year ago. Goux won three trophies, Remy Brassard, for leading at 200 miles, the Prest-O-Lite for leading at 300 miles and the Wheeler and Schebler for leading at 400 miles.

But if France was first and carried the coveted $20,000 to foreign shores, American brawn was well to the fore and captured second and third places for the Stars and Stripes, yielding fourth position to England, fifth to Belgium and the remaining five places to America.

Spencer Wishart in a Mercer was second, traveling 73.49 miles per hour, nosing out his fellow-American, Charles Merz in a Stutz by the narrow margin of 36 seconds.

The English Sunbeam piloted by Guyot, a Frenchman, was fourth at 70.92 miles per hour, and fifth position went to Pilette of Brussels driving a Mercedes-Knight sleeve-valve motor entered by E. C. Patterson, the Chicago sportsman. The Mercedes-Knight, one of the smallest motors in the race, 250 cubic inches displacement in a 450-cubic inch class, averaged 68.14 miles per hour and made one of the most consistent performances of the day.

Five other cars finished, making ten in all to complete the five centuries. Their order was: Howard Wilcox in the Grey Fox, a special car built by C. P. Fox, an Indiana sportsman, speed 67.65 miles per hour; Ralph Mulford in a Mercedes, poppet-valve type, 66.94 miles per hour; Louis Disbrow, Case, 66.79 miles per hour; Willie Haupt, Mason, 63.48 miles per hour; and George Clark in a special car, the Tulsa, built by Oklahoma sportsmen, speed 62.98 miles per hour.

Only Eleven Cars Finished

Only one other car was running at the finish of the ten who divided the money among them, it being Bob Burman’s Keeton which had led for many miles during the early hours of the contest but lost hours due to puncturing the gasoline tank, having to change carbureters and his carbureter catching fire.

Of the twenty-seven starters, sixteen fell by the wayside for one cause or another. The race, though slower, was a more enjoyable and fascinating one than that of a year ago, the slower pace not being recognized by the contestants because of the changing positions of the leaders until the 400-mile mark was reached, after which the Peugeot was never headed off and started opening a gap of 3 minutes between it and Gil Anderson’s Stutz which disputed every mile of the race until eliminated at 460 miles when running in second place by a broken camshaft. From 3 minutes the gap grew to 4 at 440 miles, then to 6 at 460 miles, then to 12 at 480 miles, and finally ended in a lead of 13 when the checkered flag was reached.

Today’s race was one of thrills, yet remarkably free from accidents, only one marring the sport, that being the overturning of Jack Tower’s Mason at 125 miles, Tower suffering a broken leg and his mechanic some fractured ribs. Scarcely had the starter’s flag been laid aside when the crowd was stirred by the struggle of the American drivers with the pick of France, Goux and Zuccarelli in their Peugeots. Bragg, who had the inside position in the front line of starters, took the advantage and led the field for the first lap; Evans put No. 5 Mason into the lead for the second lap; he held it in the third but Goux came into the front on the fourth, held it by 200 yards in the fifth, increased it to 400 in the sixth, added a little more in the seventh and gained some more in the eighth. With eight laps, 20 miles, covered, it looked as if the much-touted Goux was going to make a runaway of the day. But the hopes of his admirers were short lived for Burman, who was late reaching the starting line due to replacing a broken steering knuckle, and who got away at the tail end of the list, was getting his graceful Keeton under way and at 40 miles was leading the Frenchman by 2 minutes, Goux having blown a tire 20 minutes after the start and requiring 78 seconds to change his wheels with tires.

Burman a Possible Winner

Burman had his Keeton running perfectly, hitting over 100 miles per hour on the straightaway and coasting the turns. It looked as if his chances were good. At 60 miles he had 3 minutes‘ lead on the Frenchman with three other cars between him and Goux. At 80 miles he still led with over 3 minutes leeway, at 100 miles he retained a good margin; at 120 miles he still led, but fortune failed him, his carbureter caught fire, he lost nearly an hour and Goux took the lead at 140 miles with Anderson’s Stutz, Mulford’s Mercedes and Guyot’s Sunbeam all bunched 3 minutes behind him. Once more it seemed Goux’s chance to pull away if his tires would only hold up. They did and he led for another 100 miles until pushed out of position at 240 miles by the Anderson Stutz and Mulford in the Mercedes. At 260 miles the Frenchman got the premier position back with a margin of less than a minute. Mulford and Anderson hung on with the desperation of demons. At 300 miles Goux had opened a gap of scarcely 2 minutes on Anderson but at 320 Anderson was back in front with 23 seconds on the Peugeot.

But fortune changed and positions went up and down. Goux took the lead at 340 miles and held it to the end. For 120 miles Anderson’s Stutz hung onto him with determination that warmed the heart and fired the enthusiasm of every American who watched the gladiators, and until a broken part robbed him of a well-earned second place when but 30 miles from the finish.

Anderson and Goux in a Duel

Anderson and Goux were battling in a class by themselves 8 to 10 minutes ahead of the remainder of the field. It was a noble fight, with odds favoring the special Peugeot, the prize-winner for the tricolor a year ago. When Anderson coasted into the pits, lifted the hood of his motor, gave a few turns of the starting crank and then pushed his white racing machine back a pall of gloom fell over the countless thousands. America’s best fighter had given away to a foreign foe and the public looked to new leaders for America. Hopes were placed on Wishart’s Mercer and Merz’s Stutz running scarcely a minute apart. But they were 12 minutes behind the flying Goux and with scarcely 20 miles to go there was little hope of victory. Goux counted on tire trouble, but with expert pit aid he scarcely lost a minute to a change, he saw the race was won, he slackened his pace and won easily.

With first position settled, the fierce duel between Wishart and Merz for second position and the $10,000 purse was taken up by the grandstands and bleachers. Although not in the limelight, these two had been waging equal warfare from the very start of the grind. They were generally 4 or 5 minutes back of the leaders until the 400-mile mark when they were 13 or 14 minutes back of the Frenchman.

From the drop of the flag to the finish it was a neck-and-neck battle between Wishart and Merz, with but 35 seconds separating them at the finish. First one had the advantage, then the other, with not a minute separating them for over 300 miles. Merz led his rival by 26 seconds at 100 miles; at 200 Wishart led by a minute and a half; at 300 miles Wishart had his greatest margin, nearly 6 minutes; at 400 miles Merz had reduced it to less than 2 minutes; at 420 miles Wishart led by 9 seconds; at 440 miles he was 58 seconds up; at 460 it was 51 seconds, at 480 but 29 seconds, and then 35 seconds apart.

Merz’s finish was spectacular in the extreme. Just as he got the green flag, meaning that he started his last lap, flames burst out under the bonnet at each side. Simultaneously the cry went up „He is on fire.“ All looked for him to stop, but, never slackening his pace, Merz sped for the finish. Up the back stretch the flames could be seen gaining headway. Everybody wondered if he could make it, wondered if the insulation on his wires would bring him to the tape or if second or third position would be snatched from him as was De Palma’s lot a year ago. Every eye followed the white racer around the far turn, back of the bushes and then into the home stretch. The flames brightened but Merz held his pace and as he shot over the line with the mechanic vainly endeavoring to keep the flames under the hood he was given a cheer that rarely is accorded to a third-place car. The 35 seconds meant $5,000, the difference between second and third places.

Sunbeam Pleased I. A. E. Men

The Sunbeam, winning fourth place, gave all the visiting English engineers, the guests of the American Society of Automobile Engineers, a chance to wave their Union Jacks from a private stand erected for them close to the timers‘ pagoda. The running of this car was one of the consistent features of the race. Guyot put it into fourth place at 60 miles and held it in fourth, fifth, sixth or seventh position until 400 miles when he moved into fourth and held it to the finish. The car, with its long bottle-shaped black body, moved with the utmost ease, its long wheelbase handicapping it slightly on the turns. Guyot never pushed it. He was playing the safe game from start to finish, being determined to end within the money, of which he eventually carried off $3,500. He changed but one tire from start to finish.

Mercedes-Knight Very Consistent

If the consistency of the Sunbeam was noteworthy that of the Mercedes-Knight was more so. It being the first Knight-type motor to be seen in a race of any nature in America its performance was watched with the utmost interest. It had a piston displacement of 250 cubic inches as compared with 450 of the Peugeots. Pillette, who sells the car in Belgium, started on a 75-mile an hour clip. He started in eighteenth position; at 100 miles he was tenth; at 200 miles he was ninth; at 300 he was seventh; at 400 miles seventh, and at the finish fifth. So consistent was his work that everybody felt from the start he would finish well up in the money. He finished 45 minutes after Goux. At 100 miles he was 4 minutes back of Goux; at 200 miles 16 minutes; at 300 miles he was 21 minutes back, and at 400 miles 29 minutes.

A contender all through the race and one who might have finished in second or third place had he not carelessly run out of gasoline on the backstretch and lost half an hour getting a supply from the grandstand, was Ralph Mulford in No. 29 Mercedes. Mulford made one of the greatest runs of the day in that he did not change a tire from start to finish and did not make a stop until the race was more than half over. He was a leading contender until the race was past the 400-mile mark when he dropped from third to seventh and was not able to regain his lost advantage. Mulford was in fourth place at 100 miles; at 200 miles he was third; at 240 miles he was second, being less than 2 minutes back of Anderson’s Stutz leading at that time; at 300 miles he was fourth, and at 400 miles he was third. Soon after came his downfall, by a shortage of gasoline. His tank held 40 gallons and was filled at the start. At 275 miles 20 gallons were added but he ran out at 440 miles. His falling from third place moved Wishart and Merz up and when later Anderson, who was running second, fell out Wishart and Merz were moved up to second and third positions. Mulford won $1,800; had he held his place he might have been second with $10,000. It was costly gasoline.

Today’s race had more than its share of troubles with cars due to a general lack of preparedness. They had not been driven enough, the parts were not well enough worn in. As a result, bearing troubles were many. Of the sixteen to fall out, at least five had troubles traceable to burned-out bearings. The Shacht broke a crankshaft; Stutz No. 3 broke a camshaft; De Palma’s No. 2 Mercer burned out a bearing; Zuccarelli in No. 15 Peugeot, a duplicate of the winner, burned out a motor bearing; Nikrent’s Case lost a bearing, and the Anel withdrew because of loose connecting-rod bearings.

Next to bearing troubles came those due to faulty gasoline lines and poor support of gasoline tanks. Two of the Isotta cars went out with leaky gasoline tanks. These cars arrived at the speedway 3 days before the race started. They were fresh from the Italian factory, where their manufacture was delayed by a strike. The bodies with the gasoline tanks in them had been built specially at an outside factory. The rivets tore through the tank walls. Harry Grant and Trucco, the Italian driver, both withdrew for this trouble. Burman in the Keeton had gasoline troubles and changed carbureters during the race, putting on a Rayfield in lap fifty-seven. Mulford had more or less gasoline trouble from the start of the race.

Peugeot’s Pit Well Managed

A measure of the glory accruing to Goux and the Peugeot car should be awarded to the excellent management of the repair pit. The Peugeot team was fortunate in having as its manager John Aitken, of National fame, whose experience in racing as a driver on the Speedway and in pit work helped him to make an efficient organization in the French quarters. He was assisted materially in his efforts by Charles Faroux, consulting engineer of the Peugeot factory.

It was a matter of question as to the effect wire wheels would have on tire wear and it was expected that this year’s race would be of some value in determining just how the wire wheels would affect the life of the casings in the race. However, the results of the race are not such that any definite statement can be made either for or against wire wheels as tire savers. Of the ten cars which finished, three of them were equipped with wire wheels and all three were well up in the money. The winner, Goux, Wishart, who took second, and Pilette, who captured fourth money rode on wire wheels, the others using wood. The Sunbeam used the demountable type.

There were a few breaks of parts that were quite unlooked-for. Two of the Masons and the Henderson had troubles with slipping clutches. Tetzlaff’s Isotta broke a driving chain on the home stretch. The driver and mechanic pushed the car into the pits only to be disqualified for pushing a car on the course. Bragg twisted off a pump shaft on his Mercer at 325 miles. H. Endicott, driving the Nyberg, withdrew under 100 miles because of the reverse shaft in the gearbox seizing. Tower’s Mason skidded and upset at 125 miles. Burman, with all his trouble, had the only car to be running at the finish of the race when ten cars had completed the course and taken all of the prizes. For consistent work he and his car deserve credit.

The elimination of cars started early in the race. Six contestants dropped out before 100 miles were covered, these being Schacht, Grant’s Isotta, De Palma’s Mercer, Zuccarelli’s Peugeot, Endicott’s Nyberg and Trucco’s Isotta.

Between 100 and 200 miles two more withdrew, Tower’s Mason upsetting and Nikrent’s Case withdrawing.

Between 200 and 300 miles only one fell out, Tetzlaff’s Isotta.

Between 300 and 400 miles a Waterloo occurred, four withdrawing, namely, Henderson, Bragg’s Mercer, the Anel and No. 5 Mason.

Between 400 and 500 miles only one fell by the wayside, it being the most pathetic of the race, No. 3 Stutz, driven by Gil Anderson, when it was in second position.

Wire wheels played a greater part in today’s race than in any previous race in this country. Four different makes were in the race, Rudge-Whitworth, McCue, Frayer and Riley. The winning Peugeot used French-made Rudge-Whitworth detachables; No. 22 Mercer used American-made Rudge-Whitworths; and No. 23 Mercedes-Knight, finishing fifth, used English-made Rudge-Whitworths. No. 31 Case used McCue wire wheels; No. 35 Mason used Rudge-Whitworth, and No. 25 Tulsa used the McCue type of wheel. In recapitulation six of the ten cars to finish were equipped with wire wheels. Burman’s Keeton, running at the finish, used McCue wire wheels and of the other contestants the three Isottas used the Riley wire wheels. It is impossible to state the accurate report of tires on wire and wool wheels with the object of gauging the relative merits of wood and wire wheels.

The tire story continues to be one of the engrossing ones of a big race. Owing to the cool weather preceding the race and the cool rains the bricks of the speedway were cooler than usual, but still much tire trouble developed. The right rear wheels suffered the most. Then came the left rear and lastly the right front. The left front tires gave little if any trouble. Goux, using Firestones, changed nine, five on the right rear, two on the left rear and two on the right front. The left front tire went through the race and was little worn at the finish. The big reason for wearing out the right rear was because of getting off the smooth oiled center of the track. The rear wheels invariably slipped on the oily stretches and the dry, rough bricks tore the treads clean off several tires as the wheels spun around at great speed.

The most remarkable tire performance of the day were the Braender tires on Mulford’s Mercedes. These are single-cured wrapped tread tires, made in Rutherford, N. J. By single cure is meant that the carcass and tread portion of the tire are all vulcanized together in one process, whereas in many tires there are two curing processes. Mulford’s rear tires did not have a mark on them at the end of the 500 miles. There was one short cross-cut in the right front.

Various other makes of tires were represented in the race. No. 22 Mercer, which won second place, used Michelins in front and Firestones in rear. No. 2 Stutz used Michelins all around. No. 9 Sunbeam used English Dunlops and changed but one during the entire race. No. 23 Mercedes-Knight used Michelins. No. 12 Fox used Michelins.

Practically all of the contestants used shock-absorbers in front and rear, some contenting themselves with one set of four but many others putting on two sets or eight in all. Hartfords were in general use with a few of other makes. Both Peugeots used eight Hartfords each. The Mercer used a set of four Hartfords and on the Stutz finishing third were two Hartfords in front and four in rear. The Sunbeam used four Hartfords in front and a hydraulic set in rear. The winning Peugeot used Bosch ignition and a Claudel carbureter.

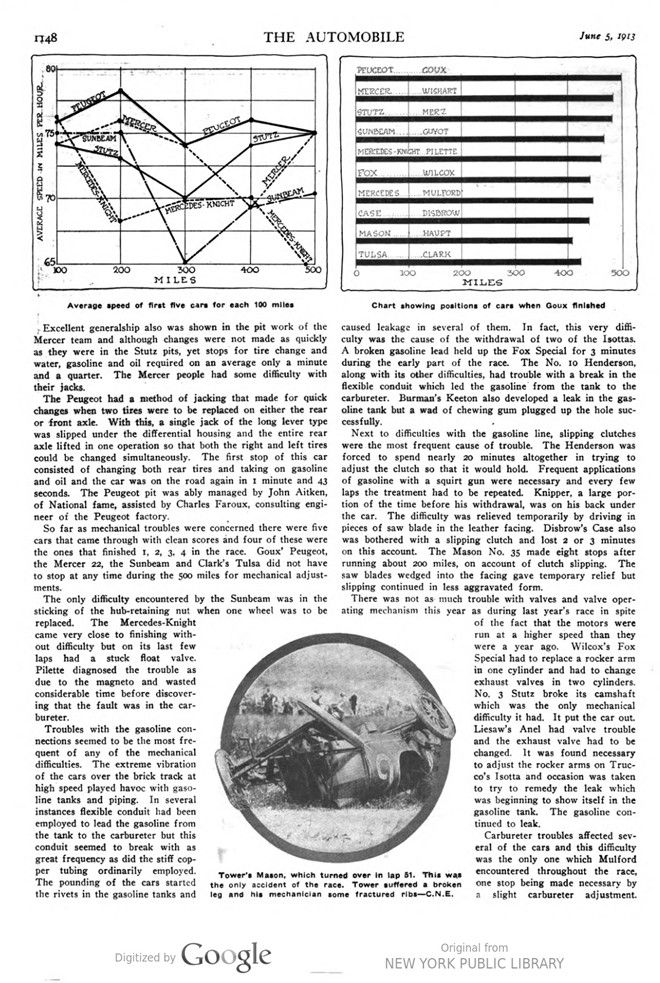

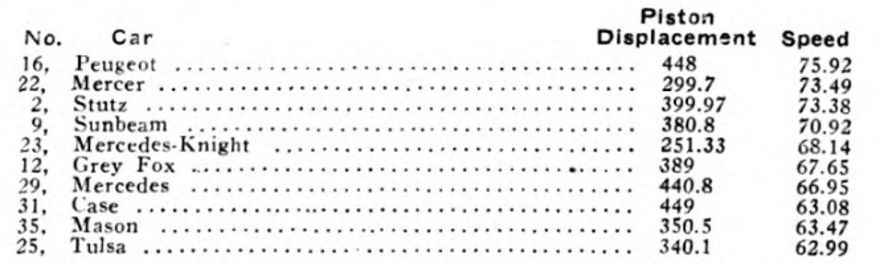

Some conception of the relative performances of the ten cars completing the race can be gained from the accompanying table, which gives their piston displacement and the speed in hour that they miles per averaged. The Peugeot was right up to limit and so was the Case.

These were the only cars to exceed the 400 cubic inch mark, the limit set by the rules being 450 cubic inches. 28 Mercer, and No. 23 Mercedes-Knight were the smallest capacity motors in the race, the Mercer 299 and the Mercedes-Knight 251. It would be possible to use a 400-cubic-inch limit next year and have practically as fast a race as that run this season.

To the Stutz team belongs the palm for quick and efficient pit work and to the men in the Stutz repair pit must be given a great measure of credit for the excellent showing made by Merz’s car. In the matter of tire changes particularly did Stutz teamwork show up brilliantly. Tire changes were made in 30 seconds flat in some instances. The average time required to change the tires on the Stutz car was about 45 seconds and opportunity was taken during this time to renew the supplies of gasoline, oil and water.

This showing was due not only to the training of the pit men but also to the preparation and arrangements that had been provided for fast work. For instance, the jack used was a long wooden lever which lifted the wheels clear of the ground with one movement, an iron strap acting as a catch which was released by a kick and let the wheels which had already been started spinning down on the ground. Another feature of the preparation was the special funnels which could be dropped into the filler opening and the can of gasoline or oil up-ended into them without wabbling.

Excellent generalship also was shown in the pit work of the Mercer team and although changes were not made as quickly as they were in the Stutz pits, yet stops for tire change and water, gasoline and oil required on an average only a minute and a quarter. The Mercer people had some difficulty with their jacks.

The Peugeot had a method of jacking that made for quick changes when two tires were to be replaced on either the rear or front axle. With this, a single jack of the long lever type was slipped under the differential housing and the entire rear axle lifted in one operation so that both the right and left tires could be changed simultaneously. The first stop of this car consisted of changing both rear tires and taking on gasoline and oil and the car was on the road again in 1 minute and 43 seconds. The Peugeot pit was ably managed by John Aitken, of National fame, assisted by Charles Faroux, consulting engineer of the Peugeot factory.

So far as mechanical troubles were concerned there were five cars that came through with clean scores and four of these were the ones that finished 1, 2, 3, 4 in the race. Goux‘ Peugeot, the Mercer 22, the Sunbeam and Clark’s Tulsa did not have to stop at any time during the 500 miles for mechanical adjustments.

The only difficulty encountered by the Sunbeam was in the sticking of the hub-retaining nut when one wheel was to be replaced. The Mercedes-Knight came very close to finishing without difficulty but on its last few laps had a stuck float valve. Pilette diagnosed the trouble as due to the magneto and wasted considerable time before discovering that the fault was in the carbureter.

Troubles with the gasoline conections seemed to be the most frequent of any of the mechanical difficulties. The extreme vibration of the cars over the brick track at high speed played havoc with gasoline tanks and piping. In several instances flexible conduit had been employed to lead the gasoline from the tank to the carbureter but this conduit seemed to break with as great frequency as did the stiff copper tubing ordinarily employed. The pounding of the cars started the rivets in the gasoline tanks and caused leakage in several of them. In fact, this very difficulty was the cause of the withdrawal of two of the Isottas. A broken gasoline lead held up the Fox Special for 3 minutes during the early part of the race. The No. 10 Henderson, along with its other difficulties, had trouble with a break in the flexible conduit which led the gasoline from the tank to the carbureter. Burman’s Keeton also developed a leak in the gasoline tank but a wad of chewing gum plugged up the hole successfully.

Next to difficulties with the gasoline line, slipping clutches were the most frequent cause of trouble. The Henderson was forced to spend nearly 20 minutes altogether in trying to adjust the clutch so that it would hold. Frequent applications of gasoline with a squirt gun were necessary and every few laps the treatment had to be repeated. Knipper, a large portion of the time before his withdrawal, was on his back under the car. The difficulty was relieved temporarily by driving in pieces of saw blade in the leather facing. Disbrow’s Case also was bothered with a slipping clutch and lost 2 or 3 minutes on this account. The Mason No. 35 made eight stops after running about 200 miles, on account of clutch slipping. The saw blades wedged into the facing gave temporary relief but slipping continued in less aggravated form.

There was not as much trouble with valves and valve operating mechanism this year as during last year’s race in spite of the fact that the motors were run at a higher speed than they were a year ago. Wilcox’s Fox Special had to replace a rocker arm in one cylinder and had to change exhaust valves in two cylinders. No. 3 Stutz broke its camshaft which was the only mechanical difficulty it had. It put the car out. Liesaw’s Anel had valve trouble and the exhaust valve had to be changed. It was found necessary to adjust the rocker arms on Trucco’s Isotta and occasion was taken to try to remedy the leak which was beginning to show itself in the gasoline tank. The gasoline continued to leak.

Carbureter troubles affected several of the cars and this difficulty was the only one which Mulford encountered throughout the race, one stop being made necessary by a slight carbureter adjustment. Burman’s chief difficulty was occasioned by carbureter troubles and he lost 21 minutes in changing carbureters shortly after noon. This, together with another 21-minute stop to fix the gasoline tank, lost him his position of leader which he had held up to that time and dropped him down to sixteenth place. Knipper’s Henderson had to stop twice, losing in all 7 minutes on account of carbureter adjustments.

Difficulties with the steering gears occurred in only two instances, Disbrow’s Case losing a nut off the tie-rod bolt and Burman having to replace a bushing on the steering gear. Burman’s trouble was to be expected in as much as he had broken a steering gear twice in practice and his final adjustments on a front axle that had just been put in that morning made him late at the start of the race.

Lubrication troubles, while they were not the direct cause of any of the stops at the pits, were responsible for some of the difficulties already enumerated. The burned-out bearings on Nikrent’s Case, Zuccarelli’s Peugeot, De Palma’s Mercer, and Harry Endicott’s Schacht probably all can be laid to insufficient lubrication.

Eighty-eight new tires were worn out during the race. This means an outlay for tire equipment along of between $3,000 and $4,000. Tires were eaten up more rapidly this year than in previous speedway races because the day was warm and because there were oily spots on the track in which the tires spun and rasped the treads.

The ten cars which finished together with the two contenders, Anderson’s Stutz and Burman’s Keeton, used in all fifty-eight casings. These were divided among the four wheels as follows: right rear tires, twenty-nine; left rear tires, eleven; right front tires, twelve, and left front tires, three.

Disbrow’s Case was nearly as fortunate as Mulford’s Mercedes, making the complete run with only one tire change. The Tulsa, driven by Clark, wore out only two tires. The Sunbeam, fitted with demountable wooden wheels, replaced three tires. Goux’s Peugeot wore out seven tires in all, three on the right rear, two on the left rear and two on the right front wheel. Wishart’s Mercer made the run with five tire changes. Merz changed as many tires as did Goux, but lost only 5 minutes. The Peugeot lost 10 minutes. Pilette ground off the tread of one of his tires when running off an oily spot and stopped for a change. At the same time he took the precaution of replacing the other three tires, although they showed no signs of wear. Later in the day he stopped for another tire change, rather than run the risk of blowing out. The Fox Special ate up seven tires, losing less than 6.5 minutes. Haupt’s Mason had to replace six tires, four of which were on the right rear wheel, losing 5 minutes. Anderson’s Stutz held the record.

Photo captions.

Page 1141.

Goux’s Peugeot receiving the checkered flag as the winner.

Page 1142.

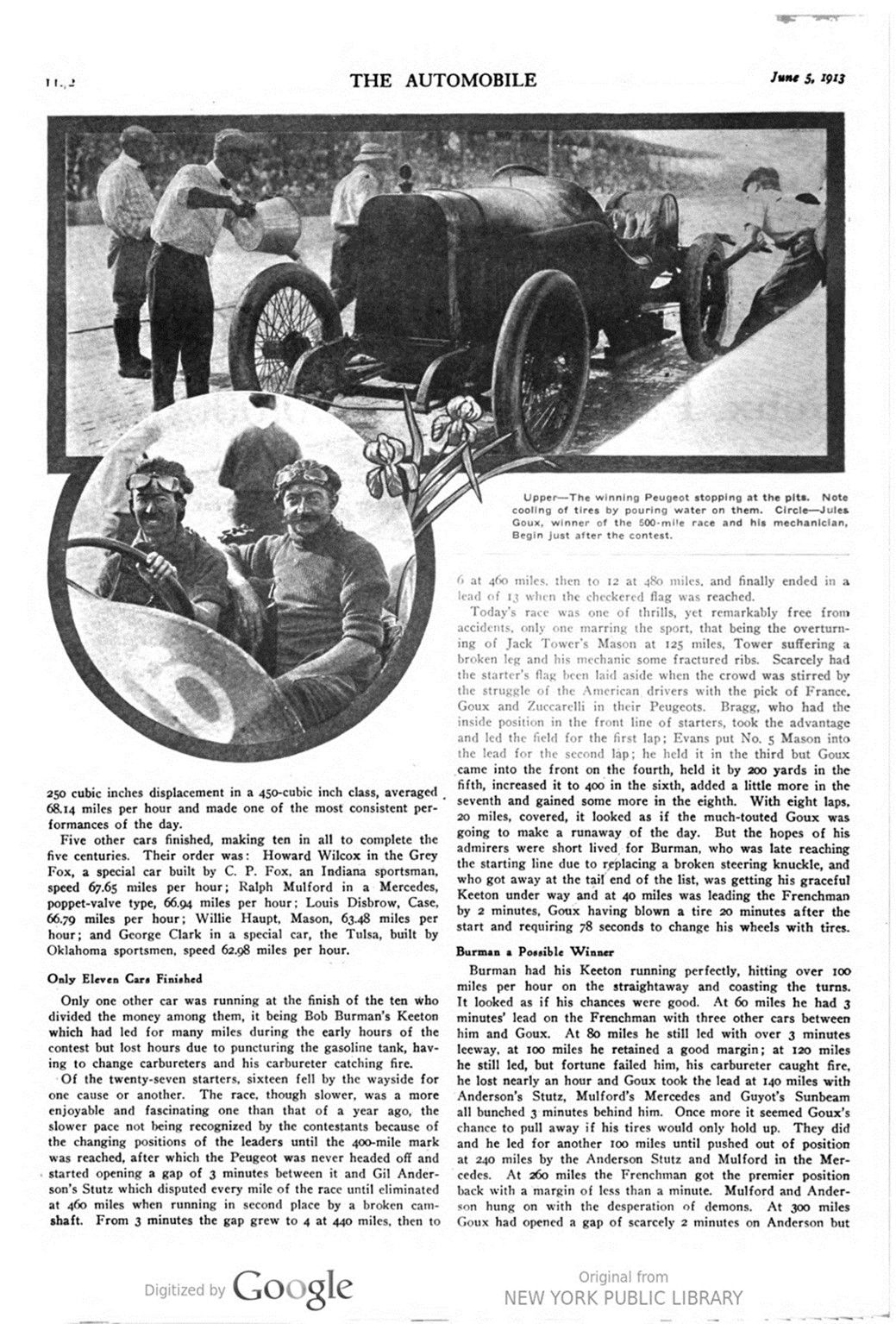

Upper-The winning Peugeot stopping at the pits. Note cooling of tires by pouring water on them.

Circle-Jules Goux, winner of the 500-mile race and his mechanician, Begin just after the contest.

Page 1143.

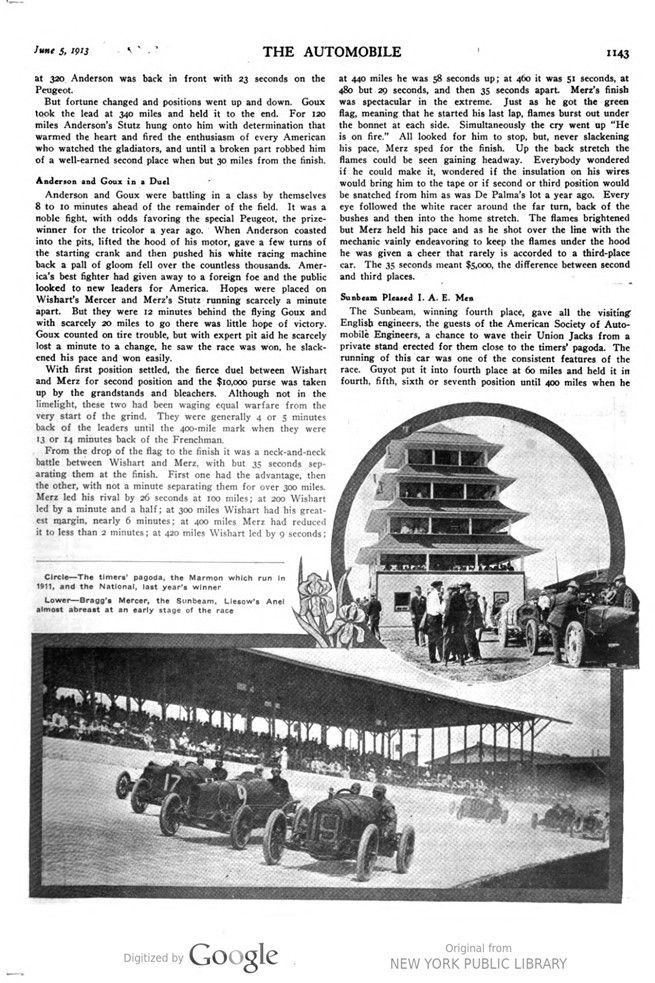

Circle – The timers‘ pagoda, the Marmon which run in 1911, and the National, last year’s winner

Lower-Bragg’s Mercer, the Sunbeam, Liesow’s Anel almost abreast at an early stage of the race

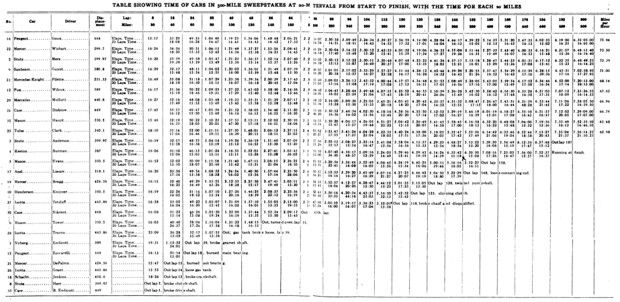

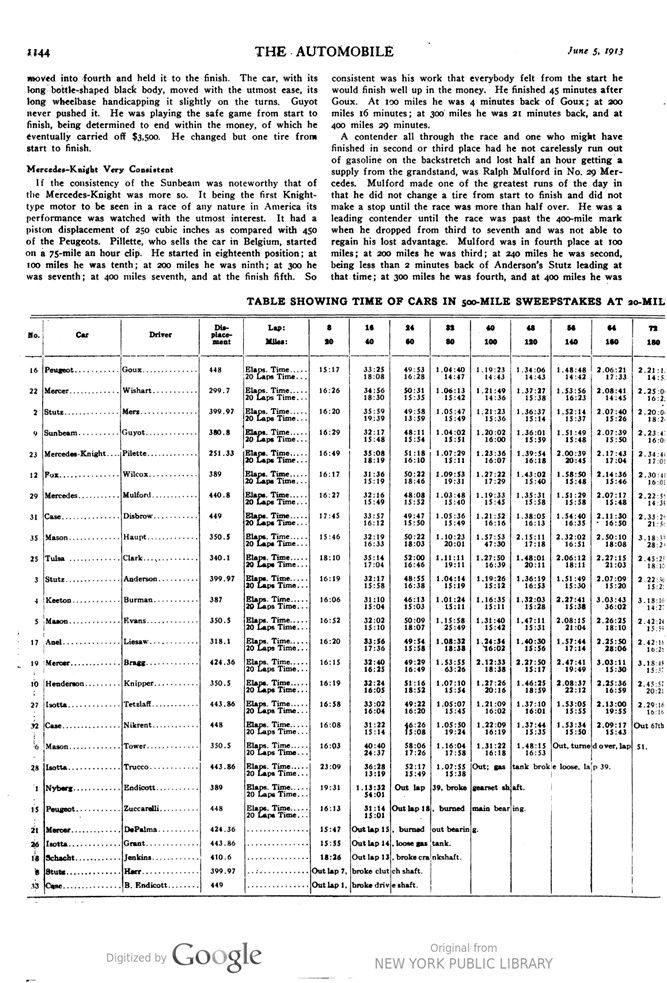

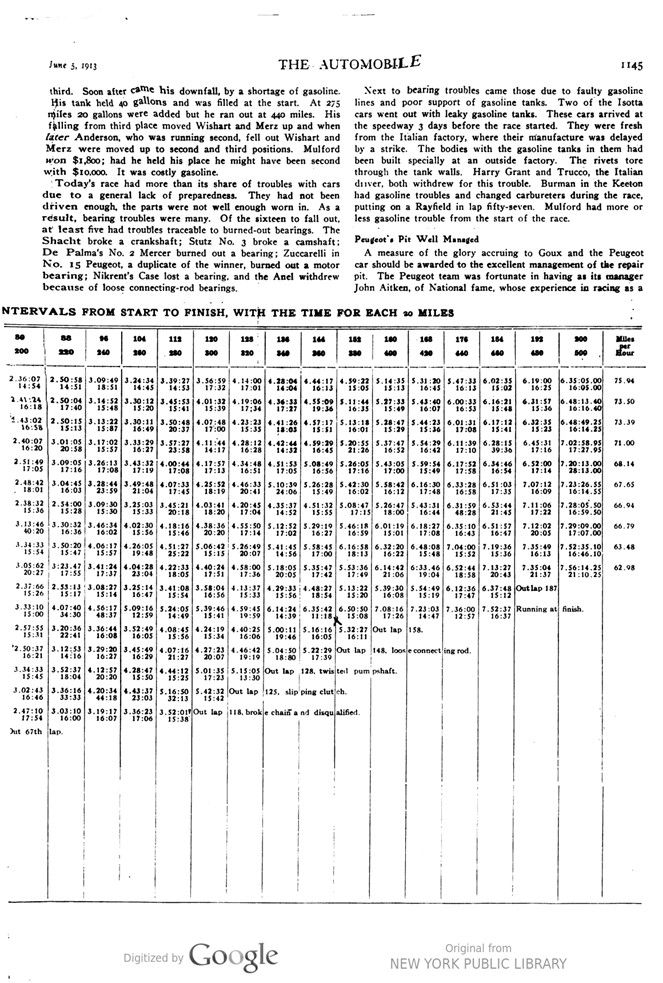

Page 1144, 1165. TABLE SHOWING TIME OF CARS IN 500-MILE SWEEPSTAKES AT 20-MILE TERVALS FROM START TO FINISH, WITH THE TIME FOR EACH 20 MILES

Page 1146.

Pilette in the Mercedes-Knight – Guyot in the Sunbeam – Wilson in the Gray Fox

A snapshot of Jenkins in his Schacht, taken just before the great contest began

Haupt and his Mason as they looked before the race

Page 1147.

Mulford in Mercedes – Case with Wisbrow driving – Clark driving Tulsa

Stutz car rounding one of the banks, with Merz at wheel – Burman’s Keeton going over 100 miles an hour

Page 1148.

Average speed of first five cars for each 100 miles – Chart showing positions of cars when Goux finished – AVERACE SPEED IN MILES PER HOUR

Tower’s Mason, which turned over in lap 51. This was the only accident of the race. Tower suffered a broken leg and his mechanician some fractured ribs – C.N.E.

Page 1149.

The $20,000 handshake of Goux and Begin, as the winners congratulated each other after the race – C.N.E.

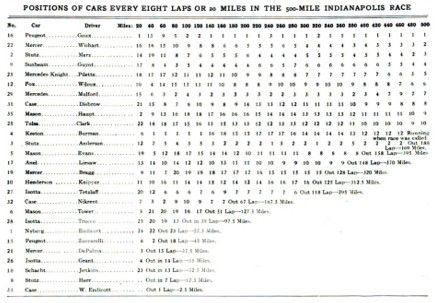

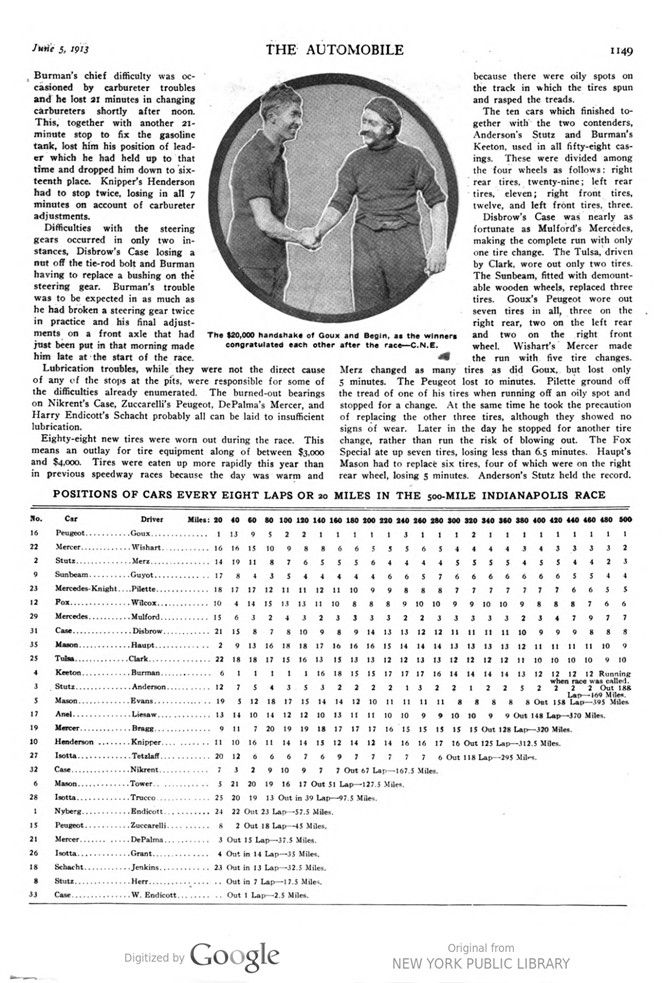

POSITIONS OF CARS EVERY EIGHT LAPS OR 20 MILES IN THE 500-MILE INDIANAPOLIS RACE (Table)