Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Motor Age, Vol. XXXVII, No. 22, May 27, 1920, page 14 – 17 / In This Issue: Indianapolis Race Entries

Decade Brings Great Races at Indianapolis

Past Contests Have Firmly Established Hoosier Track As Mecca of the Automobile Speed World

TEN years old and a veteran! Too young even for the trailing vines to have covered its board fences, yet today the Indianapolis Speedway is the Mecca of automobile engineers not only of the United States but of the whole world. A super anomaly in an industry of anomalies! A baby in years and a patriarch in traditions and accomplishments!

Those are some of the things you may think of when you watch the cars speed around the two- and one-half-mile brickway this year. It doesn’t seem so long ago when we think of 1911 in terms of anything but automobile racing, but when we look back on that first race at Indianapolis, the year that Ray Harroun turned in a victory with his Marmon Wasp, it seems a century ago, and we who saw that never-to-be-forgotten race feel like doddering veterans of a sport.

But in its ten years of life, Indianapolis Speedway has done so many things which have made the time seem longer. Followed by newer and faster speedways whose owners and promoters declared that their tracks spelled the doom of Indianapolis, the Hoosier oval alone survives. Gone are Speedway Park and Sheepshead Bay, whose tracks, much faster and newer, threatened for a minute to eclipse the glories of Indianapolis. Gone is the track at Cincinnati, another rival of a few years ago. Uniontown and Beverly Hills alone survive, and neither of them seriously threatens the pre-eminence of Indianapolis as the home of speed.

Indianapolis spells the progress of automobile engineering for the last decade. In the races at Indianapolis, you can trace the gradual development of the multi-cylinder engine. You can trace the growing strength of the lightweight car. You can trace how Europe has learned something from America in automobile engineering, returned to teach America something more and again learned something from its former pupil and erstwhile teacher.

Seven races have been run in the ten years that Indianapolice race-track has been in existence, 1918 and 1919, seeing a lapse because of America’s participation in the World War. Each of the seven races has had its own lesson to teach. Considered strictly as a sporting event, the Indianapolis race has drawn bigger crowds than any other event in American sport. Considered as a lesson to an industry, it draws more distinguished American and European engineers than any other race in motordom.

This year’s race will bring forth new principals. Unlike last year’s event, in which all except one team of cars were of a vintage of six or seven years ago, every car in this year’s race is a brand-new job. Only one is a veteran, and this one has been rebuilt so that now all that is left of the old car is its name. And these new cars embody new principles of engineering, all to undergo their first trial; a trial under the supervision of the greatest automobile engineers of the world.

1911

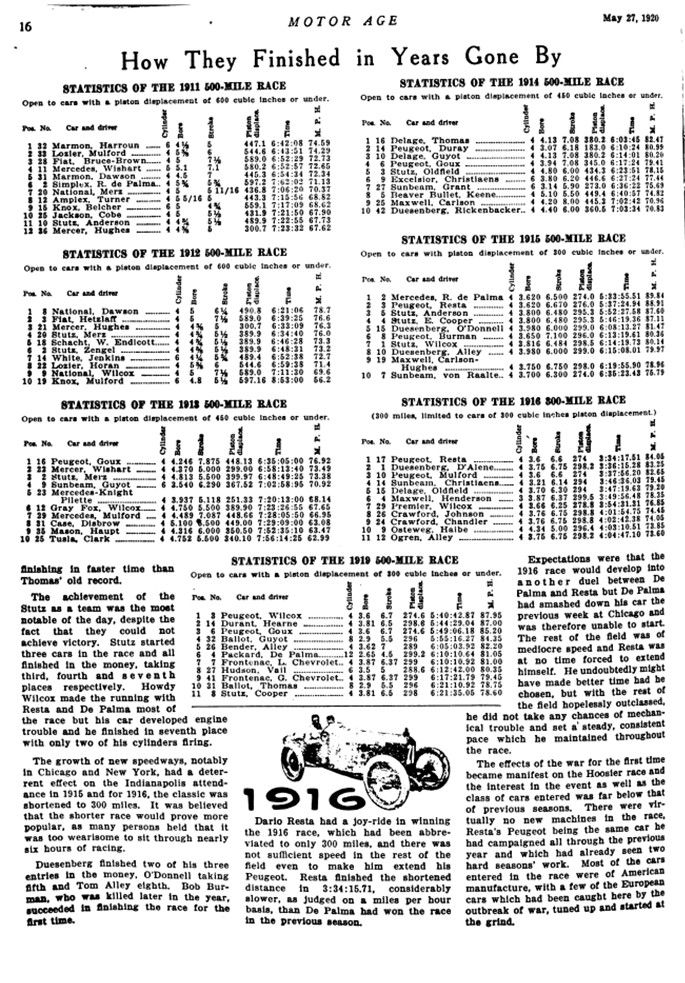

Indianapolis‘ opening race in 1911 was a fitting inaugural for a track destined to become the speed center of the automobile world. For it brought a finish unequalled in a sport which abounds in the spectacular, the first five cars to cross the line flashing over the „tape within thirteen minutes of each other. Such a finish in a great automobile race was never seen before, nor has one so close ever been seen since at Indianapolis.

To Ray Harroun at the wheel of the Marmon Wasp went the major honors of the day, but those honors must be shared by Cyrus Patschke, Harroun’s relief driver. After driving a wild race for the first 150 miles, Harroun turned his car, then in second place, over to Patschke, his relief driver, and the substitute in the next 100 miles had crept into first place, giving back the car to Harroun in a comfortable position. The finish was one of the most spectacular on record. Harroun flashed over the wire just one minute and forty-three seconds before the checkered flag was given to Ralph Mulford and his Lozier. Eight minutes and thirty-eight seconds later David Bruce-Brown thundered over the wire for third and Spencer Wishart and Joe Dawson closely followed for fourth or fifth, Dawson finishing less than thirteen minutes after Harroun had won the race.

Dawson’s finish was the most spectacular of the day. Toward the end of the race he had had a collision with another car and the radiator of his Marmon was so badly smashed that it would not hold water. With oil as the only cooling agent, he continued the race and had scarcely crossed the finish line than his engine stuck from the heat and could not be started.

Several accidents marked the race, but only one resulted fatally.

Samuel Dickson, mechanician, killed when Art Greiner’s Amplex lost tire and rim and turned over. Greiner himself escaped with some minor bruises. Dave Lewis, then a mechanician for Harry Grant, had his leg broken in a collision with Louis Disbrow’s Pope- Hartford. Several other minor accidents also occurred.

1912

To the veteran of Indianapolis races, 1912 will always be known as the year of Ralph De Palma’s Jinx. For with the race apparently won and leading the field by more than eleven minutes, De Palma’s Mercedes developed engine trouble on the next to the last lap and refused to move. With tragedy in their faces, De Palma and his mechanician pushed their car around to the pits while the whole throng of spectators seemed to unite in a groan of sympathy.

With De Palma out of the way, Joe Dawson, at the wheel of a National, was in a commanding position and wheeled over the line a comparatively easy winner, more than eighteen minutes ahead of Teddy Tetzlaff in a Fiat. Dawson’s time was a new record for the race, more than twenty minutes faster than Harroun’s winning time of the year before. Dawson’s victory was an intensely popular one, despite the sympathy felt for De Palma in his unfortunate accident. Joe was an Indianapolis boy and the car he drove was an Indianapolis built machine and before a crowd which was made up principally of Hoosiers, the victory for this combination brought an enthusiasm which has been unparalleled in any other races. Incidentally, Dawson’s victory in this year was the last gained by an American built machine.

The 1912 race was comparatively free from accidents, the only approach to a serious mishap coming when a rear wheel of Burman’s Cutting collapsed, but, fortunately, neither Burman nor his mechanic were injured.

1913

1913 witnessed the start of the invasions of European built cars and victory in the big race went to Jules Goux in the French Peugeot. It was some consolation to the American entries that Goux‘ time of 6:35:05.00 was nearly fourteen minutes slower than Dawson’s the previous year but to discount this consolation was the fact that the piston displacement limit had been lowered from 600 cu. in., which ruled for the 1911 and 1912 races, to 450 cu. in. for the 1913 race. Furthermore, second and third places were taken by Wishart in a Mercer and Merz in a Stutz, the rest of the European entries trailing these two American made cars.

The race abounded in the spectacular. For virtually the entire distance the winning Peugeot was engaged in a duel with Bob Burman’s Keeton and this contest did not end until Burman was forced to drop back when his Keeton’s carbureter caught fire.

Another spectacular incident occurred when Mulford’s car ran out of fuel on the backstretch and his mechanic sprinted a full mile across the fields of the infield to the Mercedes pit where he dropped unconscious after telling of Mulford’s plight. The effort put the Mercedes in the money. To cap the list of sensations, Charley Merz, who took third place with his Stutz, drove the last lap with his car a mass of flames.

1914

America was completely out of the running in the spectacular race of 1914 in which Rene Thomas at the wheel of a French built Delage set a new record of 6:03:45, nearly four miles an hour better than the old record held by Joe Dawson and the National.

From start to finish the race proved to be a duel between the teams representing two French manufacturers, Peugeot and Delage. There was an intense enmity between these two teams and the race brought out all the best driving in both. First the Peugeot and then the Delage forged ahead, Thomas, captain of the Delage team, and Duray, captain of the Peugeot, indulging in particularly bitter contests. Thomas had a little the better fortune, however, and flashed over the line seven minutes ahead of his rival, third place going to Guyot in another Delage and fourth to Jules Goux in the second Peugeot. Fifth place went to Barney Oldfield in a Stutz while sixth went to the Belgian Excelsior and seventh to the English Sunbeam. With six of the ten money positions and the old American record smashed to bits, there was little consolation for America in the race.

This year also was marked by one of the most unfortunate accidents which has occurred on the Indianapolis track, and which marked the end of the racing career of Joe Dawson, winner in 1912. A comparatively driver, Gilhooley, wrecked his car on one of the turns and Dawson and Wilcox, coming close behind him, seemed certain to pile up. Wilcox managed to avert an accident by skillful maneuvering but by the time Dawson had come up to the wreck, Gilhooley’s mechanician had crawled onto the track and in trying to avoid him, Dawson crashed into the bank. Dawson’s neck was broken but after several months in the hospital he finally was pronounced out of danger but never has been permitted to resume his racing career.

1915

It was not until 1915 that Ralph De Palma obtained a salve for his misfortune of 1912. In the meantime, a new racing star had flashed over the Ameri- can firmament in Dario Resta who in his first two starts in this country had taken first places in the Vanderbilt and Grand Prix races. De Palma and Resta were the outstanding favorites for the 1915 race, and they justified the faith put in them, for the grind early resolved into a duel between the two.

First one and then the other forged ahead, De Palma always seeming to have. a trifle the advantage until within a few laps of the finish Resta’s steering gear went wrong and De Palma came into a comparatively easy victory, with his Mercedes. Although the piston displacement limit for the 1915 race had again been lowered to 300 cu. in. as against 450-cu. in. the two previous years, De Palma smashed the previous year’s record to bits, wheeling his mount across the line in 5:33:55.51, an average rate of speed of 89.94. m.p.h.

Not only did De Palma smash the previous record but the next three cars in order did likewise, Resta in the Peugeot and Anderson and Cooper in Stutzes all finishing in faster time than Thomas‘ old record.

The achievement of the Stutz as a team was the most notable of the day, despite the fact that they could not achieve victory. Stutz started three cars in the race, and all finished in the money, taking third, fourth and seventh places respectively. Howdy Wilcox made the running with Resta and De Palma most of the race, but his car developed engine trouble, and he finished in seventh place with only two of his cylinders firing.

The growth of new speedways, notably in Chicago and New York, had a deterrent effect on the Indianapolis attendance in 1915 and for 1916, the classic was shortened to 300 miles. It was believed that the shorter race would prove more popular, as many persons held that it was too wearisome to sit through nearly six hours of racing.

Duesenberg finished two of his three entries in the money, O’Donnell taking fifth and Tom Alley eighth. Bob Burman, who was killed later in the year, succeeded in finishing the race for the first time.

1916

Dario Resta had a joy-ride in winning the 1916 race, which had been abbreviated to only 300 miles, and there was not sufficient speed in the rest of the field even to make him extend his Peugeot. Resta finished the shortened distance in 3:34:15.71, considerably slower, as judged on a miles per hour basis, than De Palma had won the race in the previous season.

Expectations were that the 1916 race would develop into another duel between De Palma and Resta but De Palma had smashed down his car the previous week at Chicago and was therefore unable to start. The rest of the field was of mediocre speed and Resta was at no time forced to extend himself. He undoubtedly might have made better time had he chosen, but with the rest of the field hopelessly outclassed, he did not take any chances of mechanical trouble and set a steady, consistent pace which he maintained throughout the race.

The effects of the war for the first time became manifest on the Hoosier race and the interest in the event as well as the class of cars entered was far below that of previous seasons. There were virtually no new machines in the race, Resta’s Peugeot being the same car he had campaigned all through the previous year and which had already seen two hard seasons‘ work. Most of the cars entered in the race were of American manufacture, with a few of the European cars which had been caught here by the outbreak of war, tuned up and started at the grind.

1919

After a lapse of two years on account of America’s participation in the World War, an attempt was made to revive the racing game at Indianapolis with another 500-mile race. From a viewpoint of interest and attendance it was a big success, but these were the only two particulars in which it was even partly so. For aside. from the satisfaction Americans might take in the fact that the race was won by an American, Howdy Wilcox, the race was a complete failure.

Several reasons contributed to this failure. First, with the exception of one team, the cars entered were of a vintage of several years previous – in fact the wonder was, not that some of these cars were extremely slow, but rather that a great many of them were able to run at all, in view of the hard knocks they had received in their long careers. Second, an inconceivable blunder kept the only new cars in the race from figuring seriously in the result.

Ballot, a French manufacturer, was the only one who had a team of new cars in the race. Considerable interest attached to these machines, for they embodied a new idea in racing cars with eight cylinders in a row. They had shown extreme speed in practice and gave every indication of having the race „sewed up.“ At the last minute, however, Rene Thomas, captain of the Ballot team, changed the wheels on the cars and the resultant change in gear ratios caused so much wheel trouble to the cars in the race that they never were serious contenders.

Wilcox‘ victory was popular, as he was an Indianapolis driver, and was comparatively easily gained. Howdy drove a steady, consistent race, knowing that his mount was faster than any other machines in the contest with the exception of the Ballots and the minute these were forced out with their wheel and tire troubles that the race was as good as won.

The race was the bloodiest in the history of the Hoosier speedway. Three men were killed outright on the track while a fourth died a few days later as the result of injuries suffered. Louis LeCocq, and his mechanician were killed when LeCocq’s Roamer overturned and caught fire; Arthur Thurman was killed when his own Special was overturned while Shannon died as the result of the most peculiar accident of the day. When Louis Chevrolet came across the line with one wheel gone from his car, the scraping axle cut the wire timing line which flew back and hit Shannon, who was close behind, severing his jugular vein and causing injuries from which he later died.