Text and pictures with courtesy of hathitrust hathtrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory

MOTOR AGE 2 Vol. VI. No. 15 CHICAGO, OCTOBER 13, 1904

AMERICA’S FIRST INTERNATIONAL RACE

Race Won by George Heath in a 90-Horsepower Panhard, Representing the Automobile Club of France

Herbert Lytle, for America, in a Pope-Toledo, Third.

Albert Clement, for France, in a Clement-Bayard, Second.

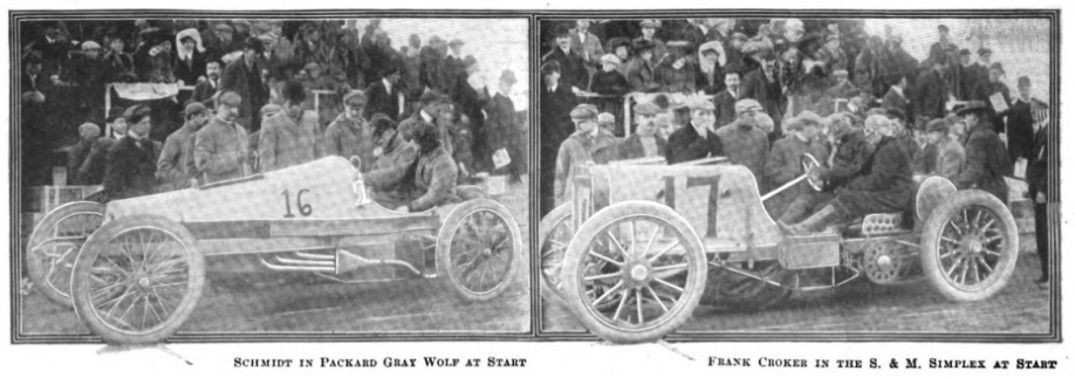

Charles Schmidt, for America, in a Packard, Fourth.

NEW YORK, Oct. 10 — America has had her first international automobile race. For the first time American motor cars and American drivers have met in speed competition European automobiles and European pilots on an American road. For all these thanks be to William K. Vanderbilt, Jr., who offered a valuable silver trophy for competition by the cars and drivers of all nations over a course on Long Island 302.4 gross miles in length with 284.4 miles of racing distance left after two controls aggregating 18 miles in the ten laps covered had been deducted. The race was run last Saturday, October 8.

Five American cars driven by Americans and six cars of European make piloted by Europeans were formally entered and competed under the terms of the deed of gift.

Seven other European cars owned and driven by Americans by an excusable stretching of the rules this time were permitted to enter and compete as representatives of foreign clubs by the latters‘ formal permission.

To the extent set forth above was the race international. It furnished as good a parison as was possible under the circum- stances of American and European cars and drivers.

On the part of the United States but two of the cars entered had been built with any idea of their taking part in this race — the 60-horsepower Pope-Toledo and the 75-horsepower Simplex. The Packard Gray Wolf was a rather low power, middle weight machine constructed for mere sprints and short distance track races. To be sure, it had accomplished a world’s record mile for its class of 462 seconds on the smooth Ormond beach, but there had never been any idea of its being put to any such test as the present The 24-horsepower Pope-Toledo was but a stock touring car, put in the contest more for an official try-out over a long distance than with any hopes of victory. The same may be said of the 40-horsepower Royal Tourist touring car. Webb, Lytle, Schmidt and Tracy had had only track-racing experience and Croker none at all.

Against the Americans were pitted a sextette of crack European drivers. Than Heath, winner of the Ardennes circuit; Gabriel, first .at Bordeaux in the Paris-Madrid and third in the Irish Gordon Bennett contest; Clement, third in the Ardennes race, and Tarte, Werner and Teste, prominent in most of the great continental road races of recent years, Europe could have asked for no higher class representation, Thery and Jenatzy, of the great ones, alone being conspicuously absent. They all had giant 90-horsepower mounts. Europe had a further representation in three other great 90-horsepower flyers — the Wallace Fiat, the Brokaw Renault and the A. G. Vanderbilt Fiat. Four other cars of 60 horsepower were in the race to do battle for European automobile manufacturing supremacy.

America was utterly outclassed in the experience of the drivers and overmatched in numbers and power of the cars.

Behold the outcome.

European cars with European drivers, first – if we resign Heath, our good American resident abroad, to the old country, as, of course, we should perhaps this time — and second, both being far ahead at the finish, in fact over a whole lap to the good.

A 24-horsepower touring car and a 30-horsepower track racing craft built and driven by Americans, third and fourth.

Of the seven surviving cars that were on the course when the race was brought to its official end there were three out of five of American build and pilotage entered, two of European make and driven out of six entered, and two foreign built and American steered out of seven entered three out of five American cars and four out of thirteen European cars.

Of the first ten in the race there were four out of five American, four out of six out-and-out European, and two out of seven European made and American driven cars — four out of five American and six out of thirteen European cars.

The Americans have seen themselves soundly thrashed by two of the best cars and drivers of Europe and have learned what it means for a car to travel over 300 miles of American road at 52.2 miles an hour, as Heath’s Panhard did and as Clement’s Clement-Bayard went within a small fraction.

Europeans have seen, on the other hand, four of their crack cars and chauffeurs put out by two light-powered Yankee machines, one a mere touring vehicle and four out of five American cars entered very much in the running after three-fifths of the journey had been accomplished.

All hands on both sides have been compelled to pause and reflect whether, after all, cars of medium power and weight are not the more likely combination to survive in a long distance run over even the best of average American roads, which the Long Island course certainly represented. Europeans may perhaps be brought to the conclusion that Americans in building as they are, are building best for their own needs and those Americans who have been importing high powered European cars may now take a bit notice of the lighter weight and powered vehicles their own countrymen are, turning out for home users.

So far as management went, Americans have no reason to be ashamed of the conduct of their first attempt at long distance road racing. Mr. Vanderbilt, donor of the cup, and A. R. Pardington, chairman of the commission, on whom fell practically the entire details of the preliminaries and the running of the race itself, were handicapped from the start by lack of full legal power and up to the very last moment by the stubborn opposition of a considerable contingent of Nassau County citizens. They had no course given over to them without dispute by the government, with soldiers furnished to enforce their rights and keep the course clear. The state statute merely gave the county supervisors power to suspend the speed limit. That was all. Country constables alone were obtainable at the expense of the promoters to patrol the course. Yet despite all this the untrammeled and restraint-hating American public at large kept off the course enough to obviate any serious impediment to the racers. In fact, when the two leaders crossed the tape automobilists themselves were the chief transgressors in encroaching on the course and compelling the official calling off of the contest through fear of some accident.

One fatal casualty unfortunately occurred, in which a participant and not a spectator was the victim. Too much pluck in persevering with a flat tire brought disaster to George Arents, Jr. The front wheels of his car finally gave way at the Queens turn, causing an upset and fracturing the skull of his mechanic, Carl Meusel, and it is feared his own also, whereby he lies at this writing in a critical condition at the hospital at Mineola, though tonight’s report here gives less cause for alarm. Meusel died Saturday.

Every detail of management and conduct as set forth in the preliminary announcements in these columns — telephone service, handling of controls and timing — were carried out to the letter without a hitch. The members of the Chronograph Club of Boston, who had charge of the timing, deserve the highest praise. They were able to announce the net time of each man as he crossed the tape each lap and had ready for the officials at 9 o’clock on the night of the race a complete table of all the finish and control times.

There are various estimates of the size of the crowd that witnessed the race. Some place it as low as 15,000, estimating the spectators as low as 500 per mile of the circuit. A program man, who sees big crowds and made a circuit of the course that day, puts the number at 50,000, declaring there was hardly a break in the line of spectators and that at each of the controls and towns were crowds numbering up in the thousands. Not one complaint, though, was made by any racer of having been interfered with by the spectators. There were reports, either, of wagons on the road.

In obviating the dust evil, the oiling of the course with 90,000 gallons of crude petroleum at a cost of $5,000 was an entire success. A dustless road will remain for months as the heritage of the contest to the farmers.

It is understood that the receipts from the sale of grand stand boxes and seats, the official program and entrance fees with a liberal contribution from Mr. Vanderbilt will cover the cost of the race without having recourse to the guarantee fund.

Under the conditions of the deed of gift the next race for the cup will take place in this country.

In view of the freedom from accidents to spectators and the great revenue that came to Nassau County thereby, it is not believed that there will be any opposition to the race next year.

It seems certain that the great showing made by American cars in the first race will assure a more serious and adequate representation of American makers at the next contest.

“I spent all my time at the controls and foreign stations to learn how they ran the game, “ said Barney Oldfield. “I have learned a lot and have an opinion of just what a car should be for such a race. I am going to have a try for the Gordon Bennett cup next year and you can say that my car will weigh less than 1,800 pounds.“

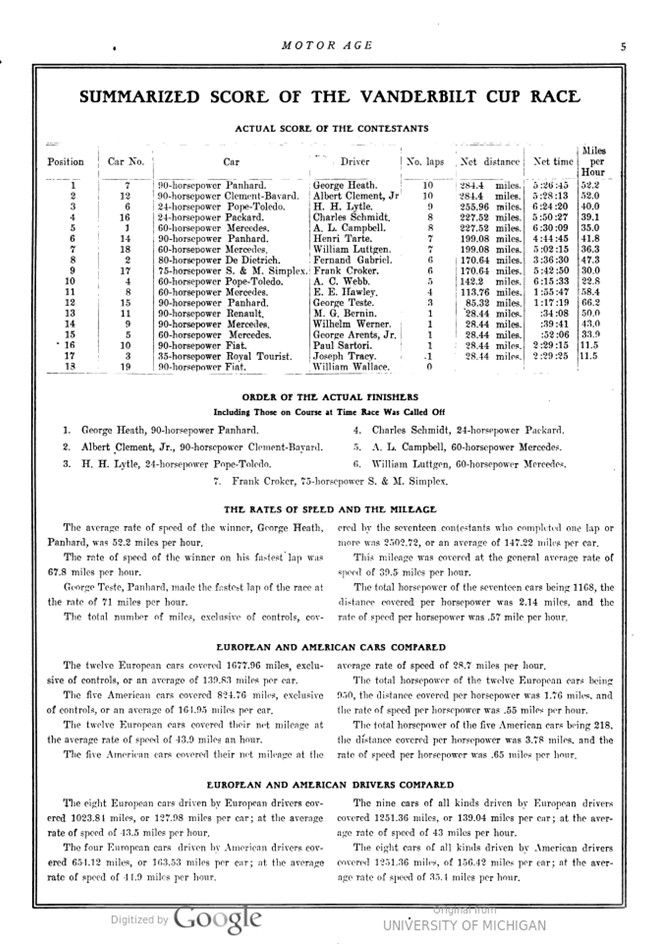

SUMMARIZED SCORE OF THE VANDERBILT CUP RACE

ORDER OF THE ACTUAL FINISHERS

Including Those on Course at Time Race Was Called Off

1. George Heath, 90-horsepower Panhard.

2. Albert Clement, Jr., 90-horsepower Clement-Bayard.

3. H. H. Lytle, 24-horsepower Pope-Toledo.

4. Charles Schmidt, 24-horsepower Packard.

5. A. L. Campbell, 60-horsepower Mercedes.

6. William Luttgen, 60-horsepower Mercedes.

7. Frank Croker, 75-horsepower S. & M. Simplex.

THE RATES OF SPEED AND THE MILEAGE

The average rate of speed of the winner, George Heath, Panhard, was 52.2 miles per hour.

The rate of speed of the winner on his fastest lap was 67.8 miles per hour.

George Teste, Panhard, made the fastest lap of the race at the rate of 71 miles per hour.

The total number of miles, exclusive of controls, covered by the seventeen contestants who completed one lap, or more was 2502.72, or an average of 147.22 miles per car.

This mileage was covered at the general average rate of speed of 39.5 miles per hour.

The total horsepower of the seventeen cars being 1168, the distance covered per horsepower was 2.14 miles, and the rate of speed per horsepower was .57 mile per hour.

EUROPEAN AND AMERICAN CARS COMPARED

The twelve European cars covered 1677.96 miles, exclusive of controls, or an average of 139.83 miles per car.

The five American cars covered 824.76 miles, exclusive of controls, or an average of 164.95 miles per car.

The twelve European cars covered their net mileage at the average rate of speed of 43.9 miles an hour.

The five American cars covered their net mileage at the average rate of speed of 28.7 miles per hour.

The total horsepower of the twelve European cars being 950, the distance covered per horsepower was 1.76 miles, and the rate of speed per horsepower was .55 miles per hour.

The total horsepower of the five American cars being 218, the distance covered per horsepower was 3.78 miles, and the rate of speed per horsepower was .65 miles per hour.

EUROPEAN AND AMERICAN DRIVERS COMPARED

The eight European cars driven by European drivers covered 1023.84 miles, or 127.98 miles per car: at the average rate of speed of 43.5 miles per hour.

The four European cars driven by American drivers covered 654.12 miles, or 163.53 miles per car: at the average rate of speed of 44.9 miles per hour.

The nine cars of all kinds driven by European drivers covered 1251.36 miles, or 139.04 miles per car: at the average rate of speed of 43 miles per hour.

The eight cars of all kinds driven by American drivers covered 1251.36 miles of 156.42 miles per car; at the average rate of speed of 35.4 miles per hour.

Photo captions

Page 1

HEATH FINISHING HIS 302-MILE RIDE – HEATH AT THE START

GEORGE HEATH, WINNER OF THE FIRST RACE FOR THE VANDERBILT CUP

Page 2

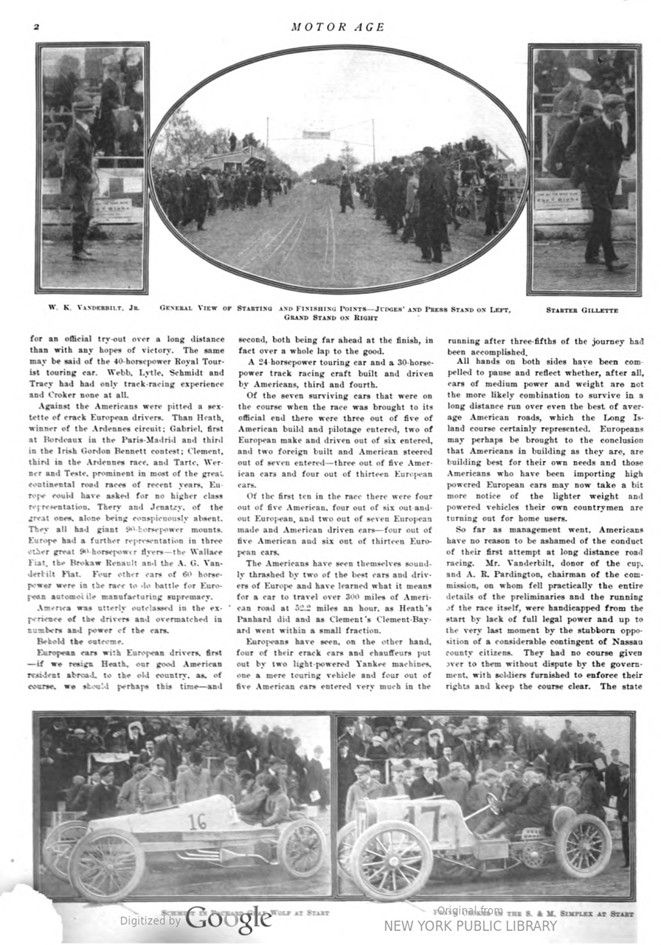

W. K. VANDERBILT, JR. / GENERAL VIEW OF STARTING AND FINISHING POINTS—JUDGES‘ AND PRESS STAND ON LEFT, GRANDSTAND ON RIGHT. / STARTER GILLETTE

16 – SCHMIDT IN PACKARD GRAY WOLF AT START

17 – FRANK CROKER IN THE S. & M. SIMPLEX AT START

Page 3

LOOKING FROM GRAND STAND BOXES ACROSS ROAD TO PRESS STAND-MRS. VANDERBILT AT LEFT