Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Motor Age, Vol. XLI (41), No. 23, June 8, 1922

From Track Crashes Comes Safety

THE reason we have faster, better and safer race cars today is because our engineers and builders have learned from wrecks. Some part lets go, perhaps. To avoid a recurrence new designs, better constructions and better metals have been developed from year to year until today we have racecars smaller, lighter, faster and safer than ever before. This experience, in turn, is reflected in the building of lighter and safer cars for the public.

How Racing Failures Have Improved Car Design

Automobile Construction in General Has Been Greatly Advanced by Application of the Knowledge Gained from Results of Terrific Strains Imposed

By B. M. IKERT

Looking over the results of the race, one is impressed by the high average speed of the place winning cars. The engines this year were of the same displacement as last year, but they were of considerably greater power than their predecessors of the same displacement. Not only was there greater power but also greater freedom from the troubles encountered in racing engines of the past. The improvements that produced the increased power also produced increased reliability.

WHILE the tenth annual Indianapolis 500-mile race was a wonderful spectacle from the standpoint of the fan, it was infinitely more so for the designer, engineer and builder of automobiles. That all of the first five cars to finish smashed the old track record for the five-century mark is an achievement, doubly so when it is considered that the new marks were made by cars of only 183 cu. in. displacement, whereas the old mark was made by a car in the 300 in. class.

Clearly, the running of this race proved more than ever the strides which have been made in the building of racing cars. Faster and smaller engines, safer cars, better steels and alloys, prettier cars, all of them the results of weeks and months experimenting and testing in laboratory and shop. No race car is built in a week or a month. What we see today on the track is the application of lessons learned in past years. It is unfortunate when a race car smashes, yet the wrecks very often have furnished the best material from which to mold new designs. Only by carefully going over a wrecked race car can the cause for the crash be determined. Maybe it was a flaw in the metal of the steering knuckle; perhaps a wheel hub wasn’t strong enough, or maybe the driver hit the wall. If he remains alive, he an tell what happened, but if he is dead, the remains of the car must be picked apart to see whether it was driver or car.

No Serious Accidents This Year

One of the most noteworthy things about this year’s race was the fact that no serious accidents occurred. In the early days when metals gave way more easily, lives were lost. People said racing ought to stop. Yet the very people who today ride on the boulevards and country roads in their cars owe much of their safety and faith in the cars they have to the boys who stake everything on a race as punishing as the 500-mile classic.

To the race spectator, the dropping out of a contestant does not mean very much, unless he is a popular driver and has the crowd with him. But, when the disabled car is wheeled or hauled to the garage, then and there begins the examination by experts. It does not stop there. When the engine or chassis is torn down later on there begins a more detailed examination of every important unit and part. Parts are micrometered and careful deductions are made in order that future efforts will be governed by what has been learned.

„Number 8 out with a broken valve spring,“ or „Number 5 out on the 27th lap with a loose fuel tank“ are expressions among those broadcasted by the announcers at a 500-mile Indianapolis race. Ever since the first race of this distance was run over the famous Hoosier oval, these expressions have been common to every race.

They have been common because there is neither man or machine that will finish the full distance in every race he enters. There is no engine that a designer and builder can enter in a race so severe as the Hoosier classic and expect that engine will be free from any trouble whatsoever. Axle shafts will break; valves will break at the neck and drop the heads into the cylinders; frames will crack; fuel tanks will become loose or leak and now and then a car will be disqualified for smoking or it may hit the wall and become disabled.

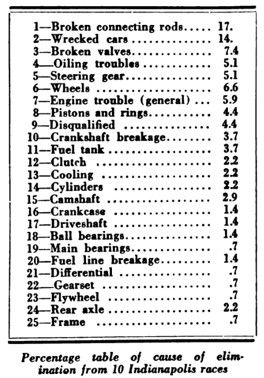

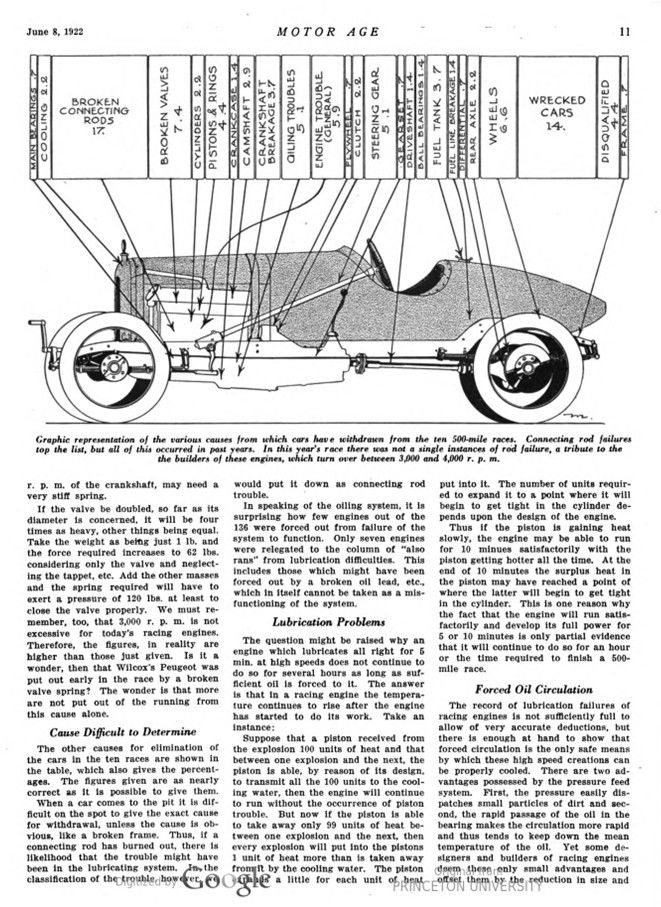

Percentage table of cause of elimination from 10 Indianapolis races

1-Broken connecting rods 17. – 2-Wrecked cars 14. – 3-Broken valves 7.4 – 4- Oiling troubles 5.1 – 5-Steering gear 5.1 – 6-Wheels 6.6 – 7-Engine trouble (general) 8.9 – 8-Pistons and rings 4.4 – 9-Disqualified 4.4 – 10-Crankshaft breakage 3.7 – 11-Fuel tank 3.7 – 12-Clutch 2.2 – 13-Cooling 2.2 – 14-Cylinders 2.2 – 15-Camshaft 2.9 – 16-Crankcase 1.4 – 17-Driveshaft 1.4 – 18-Ball bearings 1.4 – 19-Main bearings .7 – 20-Fuel line breakage 1.4 – 21-Differential .7 – 22-Gearset .7 – 23-Flywheel .7 – 24-Rear axle 2.2 – 25-Frame .7

Smaller Parts With Greater Strength

So, as long as we have cars circling the brick oval at speeds between 90 and 100 m. p. h. we are quite sure to have mechanical troubles. Some of these troubles become less common as time goes on and as our engineers and builders develop new things and as our makers of steels and alloys develop new formulas, producing metal which is stronger and lighter. In the old days of racing it was customary to make parts heavy and bulky to get strength. In today’s cars we have the same parts weighing half as much, yet twice as strong.

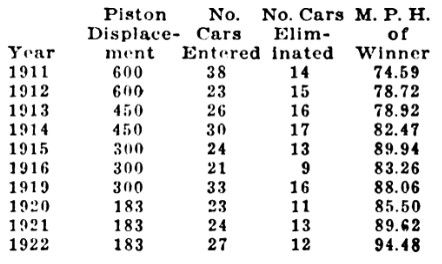

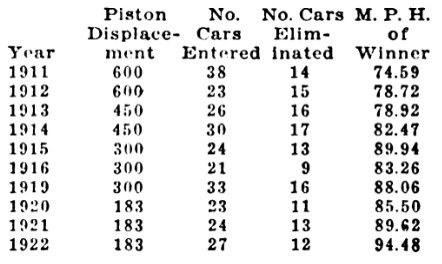

But even with this fact in hand the present day race car may develop trouble on the track. Engines are turning over much faster than they did in those days, because with a decrease in piston displacement there has come a resultant faster operating speed of the engines to get a higher maximum speed. To appreciate this one has only to note that the car which Harroun won the 1911, 500-mile race was fitted with an engine having a piston displacement of 447 cu. in. and averaged 74.59 m. p. h., while the car which Murphy drove this year was fitted with an engine close to the 183 cu. in. limit set for the cars of 1920, 1921 and 1922. Yet Murphy’s car averaged 94.48 m. p. h.

Engines With High R. P. M.

The mere fact that the engines are turning over faster and the cars traveling at a greater speed than ever before does not, however, seem to make much different in the number of cars which were eliminated due to mechanical troubles during the running of the race. For instance, the following table will show how this number varies from year to year, averaging 13 cars:

In all there were 136 cars which started in the Indianapolis 500-mile race since its inception in 1911, which were put out of the running for one reason or another. Naturally the troubles would be of a varied nature, but it is the engine as a unit which is responsible for the majority of failures. This is not to be wondered at when we stop to think that the engines in the cars of today are turning over between 3,000 and 4,000 r. p. m. and that next year’s engines, of 122 cu. in. displacement, will exceed these figures.

Burned Out Connecting Rods Lead

One must think of the terrific work which parts like the valves and pistons are doing in the time of running a 500-mile race in a little over 5 hours. It must be borne in mind, too, that these parts are operating at high temperatures and to add to the whole thing there is the vibration of the track to consider.

An analysis of the 136 failures which have occurred in the 10 Indianapolis 500-mile races which have been run to date shows that the greatest number of eliminations were caused by burned out or broken connecting rods. Twenty-three cars fell by the wayside from this cause.

Next in order comes wrecked cars, the chart showing that 19 were put out of the running from this cause. Here, however, it is possible to make a sub-division, for while a car may be classed as wrecked, the primary cause of its condition might have been due to a broken wheel, steering arm, etc. We should, therefore, have to class these as wheel or steering arm failures, etc. This is not always possible, because in a car badly wrecked it hardly is possible to sift the evidence fine enough to arrive at the exact cause.

Tremendous Valve Stresses

Valve trouble comes third in the list and this is not surprising. To appreciate the forces acting on a valve and the duties imposed on the valve spring, let us suppose that in an engine turning over at 3,000 r. p. m., which means that the camshaft is turning 1,500 r. p. m., the acceleration period of the valve, that is, the period of accelerative lift from its seat is .00294 sec. This figure is arrived at by assuming that the valve remains open for a total angular movement of the camshaft of 105 deg. and that the acceleration period lasts about one quarter of the 105 deg., or 26.5 degrees, during which travel it will have lifted half its total lift.

Now, if half the lift is 2 in. and the weight of the valve is 4 oz. then the force necessary to produce the acceleration is about 15 lbs. Add the weight of the tappet and half the weight of the spring, plus the spring pressure and it will be at least doubled. Also, the spring has to do just as much work during the first half of the closing movement of the valve as the cam has to do in the first half of opening movement, thus a 4-oz. valve if it is to follow the cam accurately at 3,000 r. p. m. of the crankshaft, may need a very stiff spring.

If the valve be doubled, so far as its diameter is concerned, it will be four times as heavy, other things being equal. Take the weight as being just 1 lb. and the force required increases to 62 lbs. considering only the valve and neglecting the tappet, etc. Add the other masses and the spring required will have to exert a pressure of 120 lbs. at least to close the valve properly. We must remember, too, that 3,000 r. p. m. is not excessive for today’s racing engines. Therefore, the figures, in reality are higher than those just given. Is it a wonder, then that Wilcox’s Peugeot was put out early in the race by a broken valve spring? The wonder is that more are not put out of the running from this cause alone.

Cause Difficult to Determine

The other causes for elimination of the cars in the ten races are shown in the table, which also gives the percentages. The figures given are as nearly correct as it is possible to give them.

When a car comes to the pit it is difficult on the spot to give the exact cause for withdrawal, unless the cause is obvious, like a broken frame. Thus, if a connecting rod has burned out, there is likelihood that the trouble might have been in the lubricating system. In the classification of the trouble, however, we would put it down as connecting rod trouble.

In speaking of the oiling system, it is surprising how few engines out of the 136 were forced out from failure of the system to function. Only seven engines were relegated to the column of „also rans“ from lubrication difficulties. This includes those which might have been forced out by a broken oil lead, etc., which in itself cannot be taken as a misfunctioning of the system.

Lubrication Problems

The question might be raised why an engine which lubricates all right for 5 min. at high speeds does not continue to do so for several hours as long as sufficient oil is forced to it. The answer is that in a racing engine the temperature continues to rise after the engine has started to do its work. Take an instance:

Suppose that a piston received from the explosion 100 units of heat and that between one explosion and the next, the piston is able, by reason of its design, to transmit all the 100 units to the cooling water, then the engine will continue to run without the occurrence of piston trouble. But now if the piston is able to take away only 99 units of heat between one explosion and the next, then every explosion will put into the pistons 1 unit of heat more than is taken away from it by the cooling water. The piston expands a little for each unit of heat put into it. The number of units required to expand it to a point where it will begin to get tight in the cylinder depends upon the design of the engine.

Thus, if the piston is gaining heat slowly, the engine may be able to run for 10 minutes satisfactorily with the piston getting hotter all the time. At the end of 10 minutes the surplus heat in the piston may have reached a point of where the latter will begin to get tight in the cylinder. This is one reason why the fact that the engine will run satisfactorily and develop its full power for 5 or 10 minutes is only partial evidence that it will continue to do so for an hour or the time required to finish a 500-mile race.

Forced Oil Circulation

The record of lubrication failures of racing engines is not sufficiently full to allow of very accurate deductions, but there is enough at hand to show that forced circulation is the only safe means by which these high-speed creations can be properly cooled. There are two advantages possessed by the pressure feed system. First, the pressure easily dispatches small particles of dirt and second, the rapid passage of the oil in the bearing makes the circulation more rapid and thus tends to keep down the mean temperature of the oil. Yet some designers and builders of racing engines deem these only small advantages and offset them by the reduction in size and weight made possible by the use of a ball-bearing crankshaft.

That which applies to the piston in the way of heat applies to every other part. The friction of the bearings heats up the crankshaft, camshaft and piston pin. The general rise in temperatures heats the oil itself. Increasing temperature causes expansion in the various parts and thus causes a reduction in the tolerances settled upon by the engineer. As the oil gets hotter its lubricating power becomes less. Therefore, if the working temperature of any parts is underestimated in the original design, then the lubrication almost certainly will prove defective in the engine if it is run continuously for a length of time.

Lubrication Failure Disastrous

While connecting rods top the list in the matter of failures, it must not be construed that the fault lies in the rods themselves. The failure of the oiling system, as was pointed out, may cause a bearing to „seize“ and result in the eventual twisting of the rod. The bearings in a racing engine which are most likely to give trouble are the lower and the upper ends of the connecting rods. These bearings are subjected to the greatest pressure per square inch.

In the matter of crankshaft bearings there are two alternative designs. One has plain bearings for both main and connecting rods and the other plain bearings for the rods and ball bearings for the shaft. There has been remarkable little trouble from main bearing failure, both plain and ball types.

The Peugeot engineers were the first to get any real success with ball bearings for the shaft and they used this type not so much to cut down friction or avoid the necessity for a high-pressure system of oiling, but to reduce the overall length of the engine and thereby I cut down its weight. They wanted to get the lightest car possible so as to obtain maximum acceleration and hill climbing ability for road racing in France. These ball bearings gave no trouble and therefore, the Peugeot de- sign has been copied extensively.

Such units as the crankcase, drive- shaft, differential, gearset, flywheel, etc. have been remarkable free from trouble so far as being primary causes for the withdrawal of cars.

122 Cu. In. Next Year

What will happen next year with the cars of 122 cu. in piston displacement is impossible to say at this time. With the smaller engines and resultant higher crankshaft speed, there will be new problems to solve. Lubrication will have to be given considerable thought and the same is true of cooling. But when we look over the accomplishments of the engineers and builders of race engines since the first running of the Hoosier classic there is every good reason that the 122-in. cars will be as fast and safe as their predecessors, the 183-in. engine, which has just finished three years of stellar performance.

Photo captions.

Page 11.

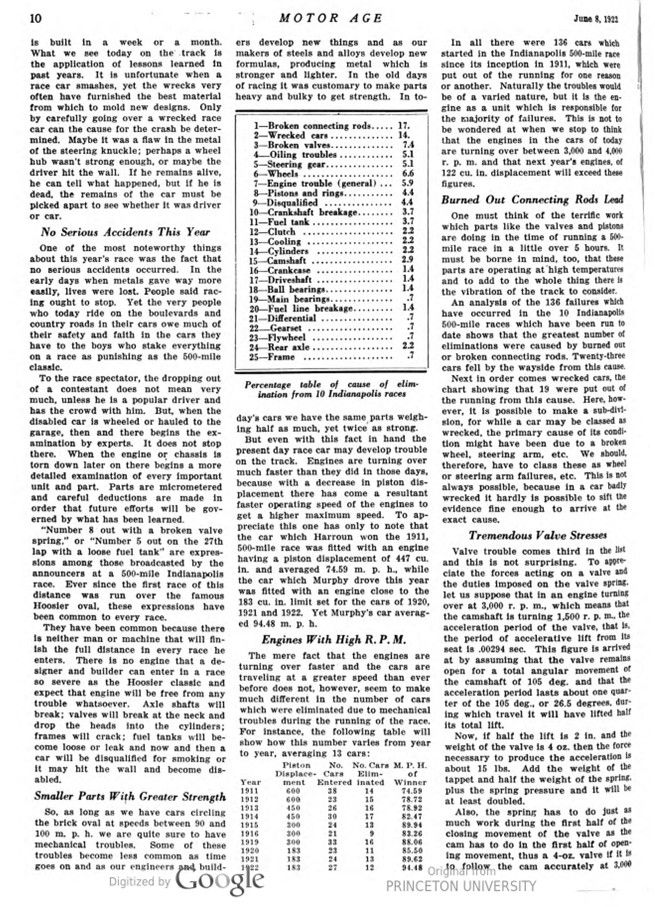

MAIN BEARINGS .7 – COOLING 2.2 – BROKEN CONNECTING RODS 17 – BROKEN VALVES 7.4 – CYLINDERS 2.2 – CRANKCASE 1.4 – PISTONS & RINGS 4.4 – CAMSHAFT 2.9 – CRANKSHAFT BREAKAGE 3.7 – OILING TROUBLES 5.1 – ENGINE TROUBLE (GENERAL) 5.9 – FLYWHEEL .7 – CLUTCH 2.2 – STEERING GEAR 5.1 – GEARSET .7 – BALL BEARINGS 1.4 – FUEL TANK 3.7 – FUEL LINE BREAKAGE 1.4 – DRIVESHAFT 1.4 – DIFFERENTIAL .7 – REAR AXLE 2.2 – WHEELS 6.6 – WRECKED CARS 14. – DISQUALIFIED 4.4 – FRAME .7

Graphic representation of the various causes from which cars have withdrawn from the ten 500-mile races. Connecting rod failures top the list, but all of this occurred in past years. In this year’s race there was not a single instances of rod failure, a tribute to the builders of these engines, which turn over between 3,000 and 4,000 r. p. m.