An enlightened report of the 1913 Sweepstakes on the Indianapolis Motor Speedway by MoToR. In my view, this magazine may not give as large reports as other magazines, but it’s journalstst surely have a good sense of humor.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

MoToR, Vol. XX, July 1913

The Flying Frenchman.

A Notable Speed Picture of Jules Goux in the Peugeot Which Carried Off First Honors at Indianapolis on Memorial Day.

Beginning with the 1912 Grand Prix de France, the triumphs of the Peugeot on track and road have been little short of astonishing. To-day there is none to dispute the Peugeot’s title to premier honors among European racing machines, unless it be the English Sunbeam with its record for remarkable consistency. But Europe proved too small for Peugeot ambitions and two of the cars were sent across the ocean for a try at the greatest prize in the motor racing world. What the result was has now become history. As Mr. Dawson tells us in his story of the race another part of the magazine, Goux (whose picture appears above), played safe and he could, if pressed, have sent his Peugeot into a world’s record. We are glad to have seen this great French machine and to have met the gallant French- man who drove it so well and who, true sportsman that he is, has announced his intention of returning to give us another chance to regain our lost laurels.

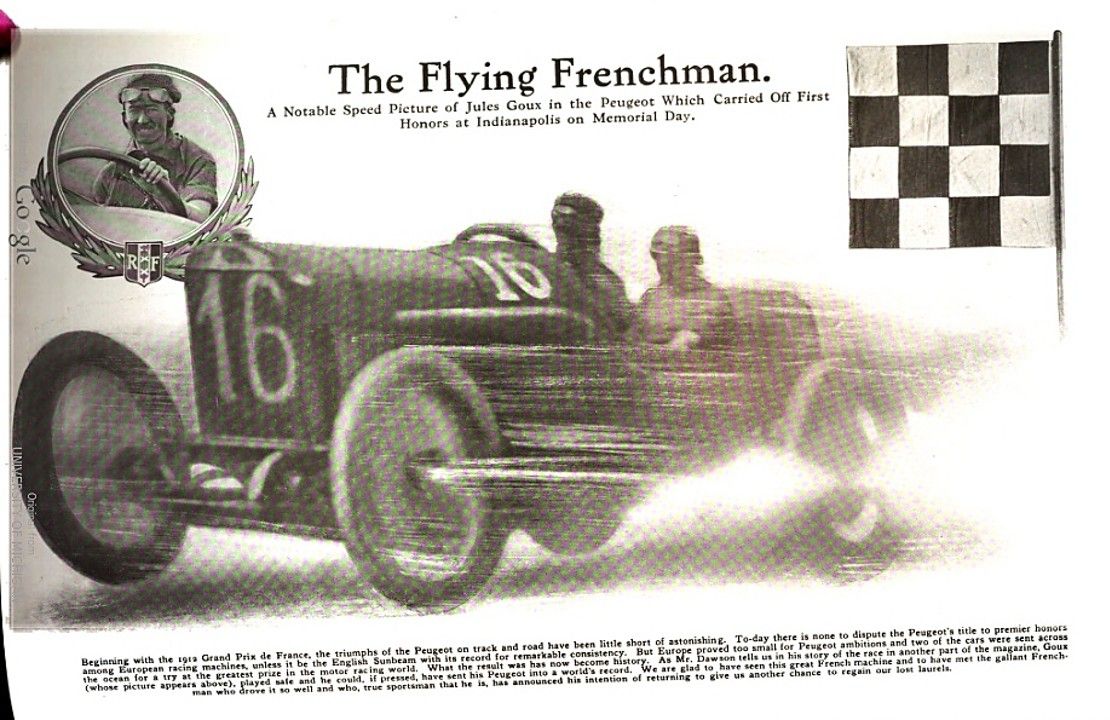

What Happened at Indianapolis.

How Four of the Greatest of American Racing Trophies Went to Take Up Their Abiding Place in France. Goux’s Winning Recipe. Gallant Struggle of the American Entrants.

By Joe Dawson.

Winner of the 1912 Sweepstakes and Holder of the World’s Records from 200 to 500 Miles with a „National-40.“

Here is a race story that is different. It is told by a man who probably knows racing from the inside better than any other individual in America to-day. Consequently, the story differs most delightfully from the general run of such accounts. – The Editor.

THE Third International Sweepstakes Race was a 500-mile parade headed by Jules Goux in Peugeot No. 16.

The most interesting feature of the affair is the after effect. Today four of the greatest racing trophies of America are held in France. It is up to the American manufacturer.

But to consider just how it happened—to figure the conditions that gave France the victor’s crown-is easy. Just now the various „authorities” are busy telling how pit-work won, how strategy in racing triumphed, how this and that and the other thing was responsible.

As far as I can see — and my attitude may be warped by the fact that I’ve viewed a lot more races from the driver’s seat than I have from the judge’s stand-here is how Goux won: During the second hundred miles he got a lead of two laps and he never dropped this lead.

That is a good recipe for winning any race — if you can do it.

But my friend from France was able and did do just that – and therein lies one of the reasons why the world’s records were not broken.

The speed of the race was set by the second car — for a hundred or so laps by Anderson’s Stutz and finally by Wishart’s Mercer. The Peugeot kept two laps ahead—at times increasing the lead to three laps in order to allow for a tire change or taking on oil or gas — excusé moi, Monsieur — I mean “essence.”

Burman’s Keeton — the favorite in the betting, the favorite of the crowds in the stands and as is often the case, the disfavored of Old Dame Fortune – set the first hundred-mile mark at 1:15:50.25, an average of 78.94 miles per hour and the fastest century of the race. It broke only the 301-450 class Speedway record, made May 27, 1910 — the reason it hadn’t been broken before this being chiefly because no one tried. When Goux got the lead the average at 200 miles dropped to 77.72 miles per hour, at 300 to 77.42, at 400 to 77.45 and the final average was 76.59 miles per hour.

All Speedway records for the 301-450 cubic inch class were broken they say. Well, there were no such records above 250 miles and the records for 150, 200 and 250 miles were made back in 1909 — the race was not startling from the speed standpoint.

Here is a comparison of time by 100 miles of last year’s race and this –

This Year. Last Year.

100. 1:15:50.25 1:13:37.25

200. 2:33:30.40 2:25:59.52

300. 3:52:26.75 3:48:49.30

400. 5:09:53 5:04:14.23

500. 6:31:43.45 6:21:06.03

Even bearing in mind the fact that this year’s race limited the piston displacement I do not think it showed any performance that American manufacturers cannot beat.

The conditions were largely to blame for the speed — the heat of the track made it a nice problem to figure how to drive best. Too much speed-hitting the turns too hard — meant a lot of time changing right rear casings.

But speed is influenced by a good many other things than what the car and driver can do. Every one of these Speedway events could average 10 miles per hour faster if the track was banked 10 feet higher on the turns. Then records would fall with a smash.

Luck is the real god of the racing game.

Science and skill and everything else is subordinate to chance on the Speedway.

Last year a foreign car led at 190 laps my National was hitting it up for second place. The foreign car went out in the last ten laps and I finished first.

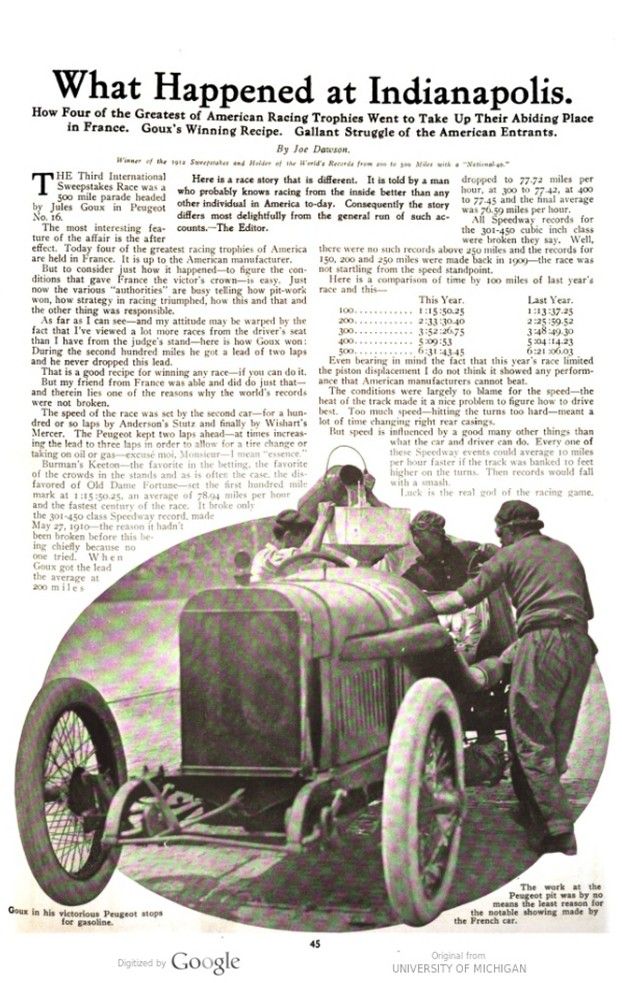

This year, the condition was the same at 190 laps – there was the foreign car in the lead, the Stutz beating it in the same relative position I held last year. But luck turned her face the other way. The foreign car came in with colors flying and Gil Anderson stopped to change a tire. When they went to crank up – Bing! $10,000 depended on starting that motor – quick. Everyone took a try at it. Under the hood a broken piece of steel – bad luck – let the Mercer romp into second place and pull down the $10,000. Two, three, four hundred mile marks passed in second place, and then to watch another car pull down the money. Well, I’ve had it happen to me, and last year when I beat it past De Palma pushing his car home, I felt that Dame Fortune had rather squared things. I hope Anderson has the turn of luck next time.

Take Zucarelli for instance, with a duplicate car to that of the winner. Burnt out bearings pulled him out of the race. Why didn’t the same thing happen to the other Peugeot? Chiefly luck, that’s what it is.

Merz and his Stutz got third in a whirlwind, pyrotechnical finish, running a lap and a half with flames shooting out underneath the car. Luck again and much if it. In the first 500-mile race, two years ago, my Marmon was running for second place to Harroun’s Marmon, the win-er. A tire lug from another car knocked a hole in my radiator a lap or so from the finish and I got only fifth place. Merz, with his car afire, held third place and finished.

The Sunbeam ran an uneventful yet consistent race into fourth place, and the Mercedes- Knight surely did make a showing. Pilette just about coasted through – the silent, smooth-running, sleeve-valve motor held what is better than extreme speed – the ability to hit a good average and keep right to it – lap after lap after lap. When you figure this was only a 250-inch motor it surely means you have to consider the Knight in future competition.

The Gray Fox-Pope-Hartford in the radiator and a Marmon in the rear axle and goodness-knows-what between, driven by Wilcox, made good in sixth place.

And when you come to analyze the individual performances, how that one word „consistency“ does stick out all over the race. Take the Sunbeam, which, by the way, is a two year old car, and see how much more its quiet, persistent plugging accomplished than great bursts of speed and tire burning. Guyot, the driver, brought the Sunbeam over on his own responsibility and without any factory help. He evidently figured that under the circumstances it was up to him to get in the money and get his investment back, and he did it to the queen’s taste.

Mulford’s Mercedes covered 285 miles without a stop – then later in the race ran out of gasoline on the back stretch and lost a lot of time and finally got past the tape seventh. This was the same car DePalma used last year with the cylinders changed to meet the 450 limitation and it surely made a wonderful showing on tires.

Disbrow’s Case, Clark’s Tulsa and Haupt’s Mason paraded into the last three sections of the prize money. Out of these ten winning cars, four were foreign, six, American. Out of the original entries, eight were foreign, twenty-two American. Half of the foreign cars finished in the money. If the three Isotta cars had had more than four days to get into the running, the percentage would possibly have been higher.

Why is it?

Next year there will be more foreign cars in American races. If we are going to have our trophies back on this side of the water, it is up to us to get busy.

From all I have seen of the foreign cars, there isn’t much doubt but what America can beat them out – if we get busy and get busy right away.

Luck breaks just as badly for the son of France or England as it does for us. It is a matter of the car, the driver plus the preparation.

It’s time right now to get ready to get back the trophies. The Indianapolis race has at last earned the recognition that is its due, as the greatest track event in the motor world. Next year we are going to have stronger foreign opposition even than this. The Sunbeam factory is already making preparations to send a factory team, especially constructed and manned, to renew its historic duel with the Peugeots. The Talbot people in England are contemplating entering some of their remarkable speed creations, and there is little doubt that the Isotta Fraschini crowd will be on hand with a thoroughly tried out team, and there will be others.

Photo captions.

Page 45.

Goux in his victorious Peugeot stops for gasoline. The work at the Peugeot pit was by no means the least reason for the notable showing made by the French car.

Page 46.

Wishart in the little Mercer he drove into second place.

Anderson’s Stutz No. 3 stopping for a tire change. This car made a gallant bid for premier honors until mechanical troubles so far put it out that eleventh place was the best it could do.

Disbrow in his Case, traveling fast on one of the turns.

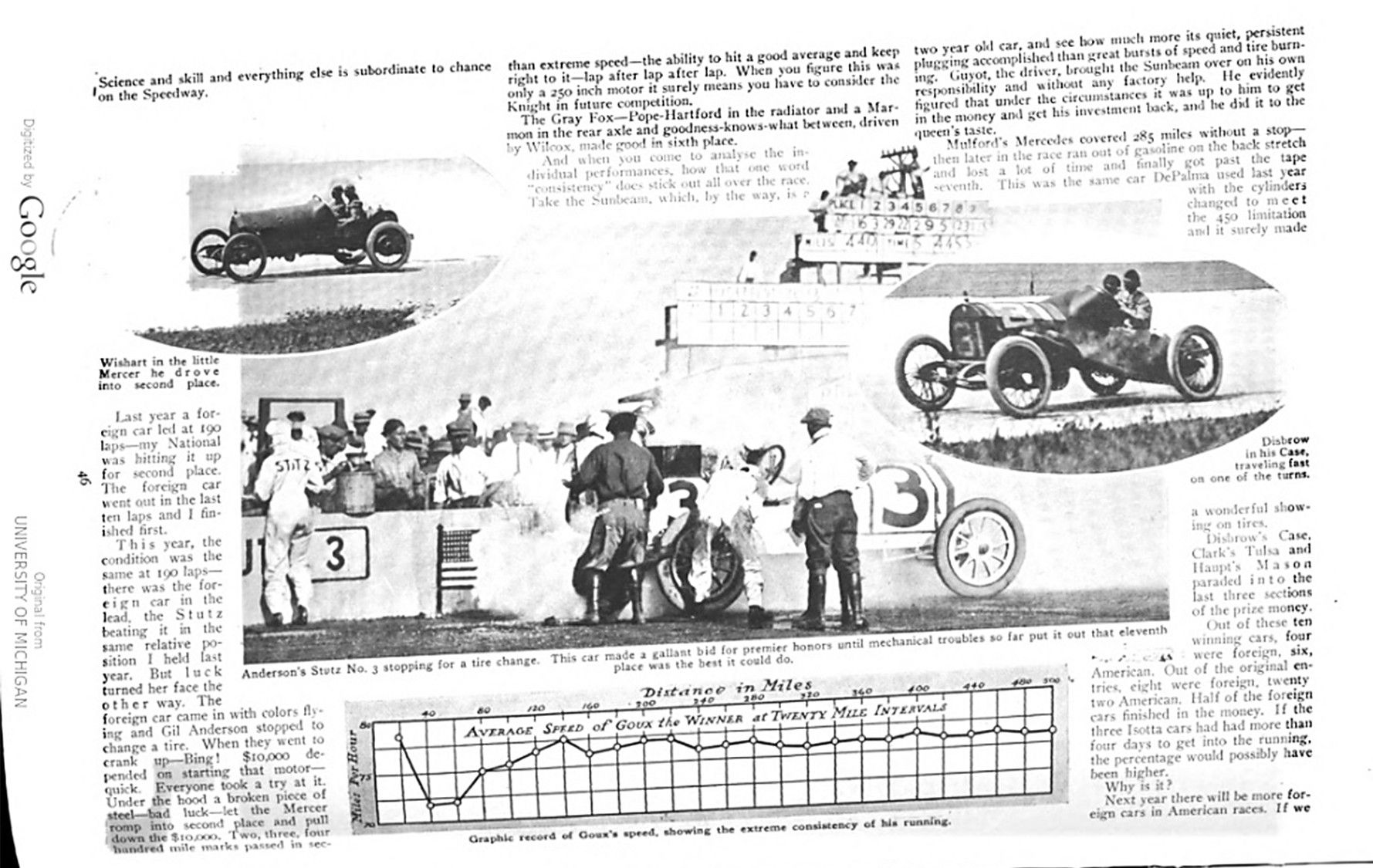

Miles Per Hour Distance Miles – AVERAGE SPEED of Goux the WINNER at TWENTY MILE INTERVALS

Graphic record of Goux’s speed, showing the extreme consistency of his running.

Page 47.

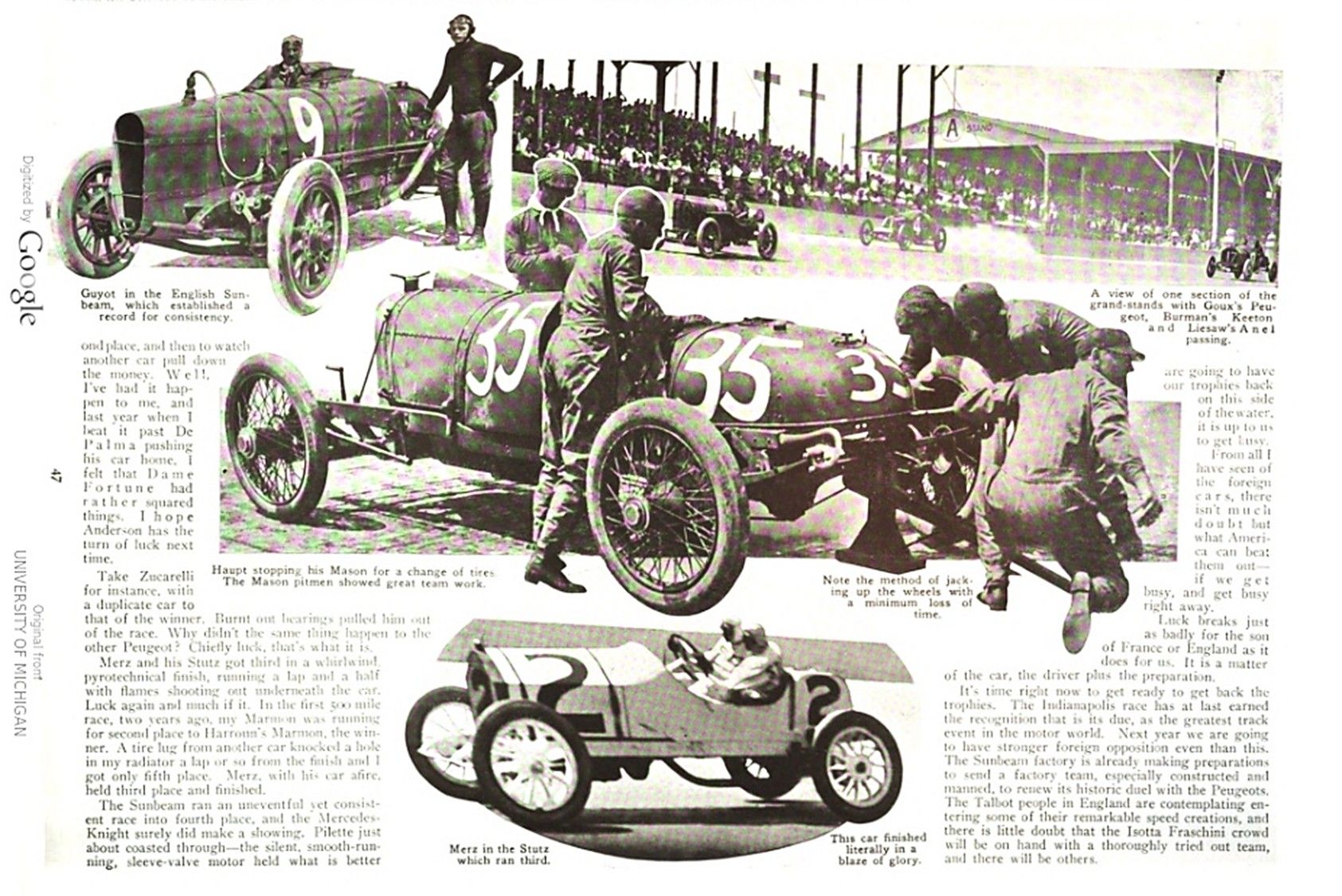

A view of one section of the grand-stands with Goux’s Peugeot, Burman’s Keeton and Liesaw’s Anel passing.

Guyot in the English Sunbeam, which established record for consistency.

Haupt stopping his Mason for a change of tires. The Mason pitmen showed great teamwork. Note the method of jacking up the wheels with a minimum loss of time.

Merz in the Stutz which ran third. This car finished literally in a blaze of glory.