An exciting story, how this 1906 Vanderbilt Cup Race and everything around it, took place. Although this story in all covers nine (9) pages, it is just as if You yourself would be a participant of this event; even of the night before! This really shows, that the Vanderbilt Cup Race itself and the spectators, was the event. This one is a very long read indeed, covering many, many pages of this issue, so that the risk of losing it may well be eminent. But just give it a try, read it and aftert that, you’ll wake up out of an era more than hundered years ago. But you were there on the spot!

Text and pictures with courtesy of Hathitrust.org hathitrust.org; compiled by motorracinghistory

MoToR, Vol. VI, November 1906

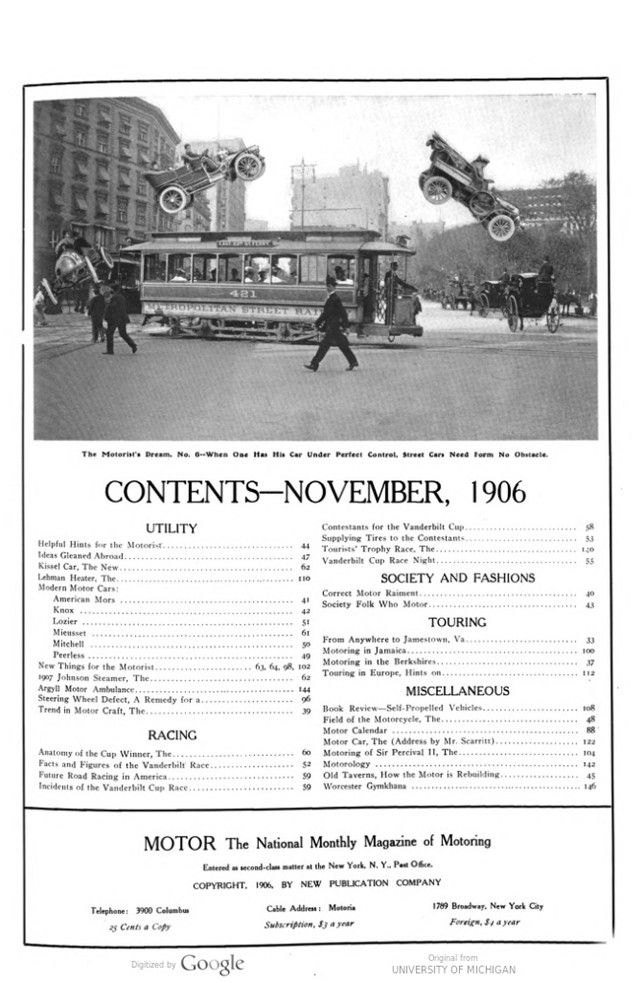

VANDERBILT CUP RACE NIGHT.

UNIQUE SCENES AND AMUSING INCIDENTS OF THE „NIGHT BEFORE“ WITH THE STORY OF THE RACE ITSELF.

The First of a Series on Motoring at Night Written for Motor by W. Parker and Illustrated with Flashlight Photographs by N. Lazarnick.

NEVER since the motor-car crept from the position of an unwelcome usurper to that of undisputed King of the Road was his pre-eminence so amazingly indicated as it was on the morning of October 6th last on the plains of Long Island. It was not a question of mere speed or horse-power that rendered this year’s cup the greatest event in the annals of the sport, for that has been equaled-nay, exceeded; but it was the unique and extraordinary scenes that preceded and attended it. The enthusiasm of the vast crowds along the thirty miles of road that made them forget all sleeplessness and discomfort in their one burning desire to see the great race was one of the most remarkable sights ever witnessed. No one who saw that wonderful living camp of four miles which lay between Mineola and the grandstand is ever likely to forget it.

Think of an army of 250,000 men! A force as huge as that which England sent out to South Africa during the great Boer War! And follow the analogy further. With a convoy, baggage train, commissariat – call it what you will – of 15,000 automobiles! As early as Thursday night full trains poured in from Western and Southern points, and every hotel in New York was full to overflowing. The garages on Broadway were besieged by inquiries by wire and telephone, offering any premium for the hire of a machine. All that was asked was that they should hold together and get to the course – and back. Ancient automobiles were taken from their lairs and brought out again into the light of day; chauffeurs with experience or without were at a premium, and the second-hand dealer reaped a golden harvest.

All through the long hours of Friday New York was filled with the fumes of gasoline and palpitating with the throb of thousands of cars. Wherever one looked it was the same; clustered in front of the great hotels, the Waldorf, Astor, St. Regis and the Hoffman House, were battalions of cars filled with wraps, provisions and other impedimenta, awaiting their owners who were hobnobbing over a final glass, or swallowing a hasty meal, preparatory to their trying journey – only twenty miles, you will say, but a twenty miles surcharged and crammed with excitements and not a few dangers. Many got away early hoping to avoid the crowd but found the crowd there before them. All the afternoon loaded cars could be seen making for the bridges and ferries, at first one and two at a time, and, as the evening gave place to night, they came in tens and dozens, till at midnight the whole city seemed to be emptying itself over the East River like an evacuated town in time of war. Some, wiser in their generation than others, foreseeing the crush at the bridges and the Long Island ferries, chose more circuit-out routes. Many went down to the South Ferry for Brooklyn, resolved to cheat the crowd that way. Like all egotists, they found others were as wise or wiser than themselves and were going that way, too. Through the tall, draughty portals of the ferry house rumbled an army of cars, blinking their feline eyes as they bumped over the drawbridge and crawled carefully aboard. Everyone talked of the race. Rumors were rife. Someone had „seen Jenatzy on board.“ One rubicund official was sure he had taken Joe Tracy’s car over the last trip; he had taken the number, even, but had forgotten it. No one undeceived him, and we left him hugging the brave delusion, as with a surge of the paddles the heavy craft lumbered out of the dock and bore off with its eager freight.

It was ten o’clock now and the „rush hours“ long over. Brooklyn Bridge slumbered calmly under a misty moon – its lofty span outlined with moving lights, as car after car stole softly out from the Manhattan side on its way to the race. Like a procession of glow worms they moved along till they lost themselves in the mazes of the dark masonry that loomed up on the Brooklyn shore.

Higher up-town at Williamsburg the scene repeated itself on a still larger scale. Everywhere automobiles were making their way to the bridge. It was Saturday night in the Jewish quarter and the streets and alleys of the Ghetto were filled with drifting crowds and blazing with light, noise, and movement. Every now and then, with a honk of the horn and a sputter from the engine, a car would crawl through the bustling throng and stop to ask the way, for it is easy to lose oneself in the mazes of the great East Side. It was a dramatic contrast. Dives reclining on his luxurious cushions-the glare of his acetylene lamps lighting up the squalid stall of Lazarus with its sordid display of damaged fruit or cheap trinklets. Not infrequently a wolfish Semitic face would come uncomfortably close, and a hoarse voice ask what was wanted.

„The bridge? Oh, dot vas easy. Turn to the right into Delancey Street. Chust so -danks!“ and a quarter would change hands, a small installment, perhaps, toward the evening up of their eternal account! Half-shamefacedly, Dives turns away, glad to escape from the piercing gaze of the man who is not only his brother in the larger sense, but can probably claim a still closer relationship, for at least Dives is no Gentile!

Down the broad, unsavory boulevard of Delancey Street an almost constant procession of cars was making its way, all heading for the big bridge; even when they had negotiated with the bridge itself, they were strangers in a strange land. Everywhere one found chauffeurs excitedly asking their way out of the wilds of Williamsburg and making confusion more ludicrously confounded by lasping into French, a language of which Williamsburg knows little, and for which it cares still less. That the Cup Race was the ultimate objective was at any rate plain to the meanest comprehension, and that lost automobiles would pay for topographical information was equally clear. In Williamsburg, at least, „for one night only,“ knowledge was power, and a little coterie at the east end of the bridge played the game for all it was worth to a tune of jangling quarters and dimes that descended alike upon the just and the unjust. For there were many of the latter. It is to be feared that the „information“ did not always lead the questioner into the straight and narrow way, but rather into some tortuous street or dark alley where a confederate was stationed who might be trusted to obtain a further disbursement in return for more geographical details, or who, in the excitement of the moment, found that the lunch basket, gripsack, or spare tire strapped to the back of the car were more easily detachable than the Owner inside seemed to think. Lost in the Ghetto to start with, and held up afterwards in the purlieus of Brooklyn, it may truly be said that many a man that night „went down from Jerusalem to Jericho and fell among thieves!“

But if the votaries of trans-pontine traffic had their troubles, those who put their faith in ferries fared little better. Naturally, the Long Island City Road was a favorite. There was a simplicity and ease in the idea of dining at the Waldorf and afterwards rolling comfortably down to the East Thirty-fourth Street Ferry while puffing the post-prandial cigar, that appealed to many. They carried out the first part of the program successfully and left the crowded palm garden in high good humor with the strains of „The Vanderbilt Cup“ ringing auspiciously in their ears. „We will be early and get straightaway to the course,“ they said, and leaned back on their comfortable cushions to dream of a record-breaking run of twenty miles over the fine Long Island roads with the moon overhead and then they woke up! They were at the corner of Second Avenue and Thirty-fourth Street. „Get back!“ „Down to the right!“ „Take your place in line!! were the only remarks of the policeman. It was too true, others were „early,“ too; hundreds of them, and many a ferry must come and go before they got even within measurable distance of their turn. At midnight the line of waiting cars had lengthened into a procession that extended as far as the eye could reach.

At the ferry all was hustle. Agents with grandstand tickets to sell at equally grand premiums thrust their heads into every window, advising, pleading, exhorting the inmates to buy seats in locations with such transcendent excellence of viewpoint that Vanderbilt himself might be proud to possess them and all this for the sum of $5. It was a cruel sacrifice but it „had to be made,“ and it was made, too, in numerous instances. Whether the magnificent seats and parking spaces thus thrown upon the market by these unselfish men realized expectations it is not for us to determine. It is to be hoped they did. Meanwhile the advertisers were not idle. One firm, which even after the lapse of days I blush to mention, had got out a line of red circular „stickers“ about the size of a dollar piece, containing more than a passing allusion to the pre-eminence of their products, and printed in that color which is the universal emblem of purity and goodness. On the obverse side was a glutinous substance which, when moistened momentarily with the tongue and applied dextrously to the woodwork or other portion of the car made a very pretty decoration and one not easily detached, as many chauffeurs have since no doubt observed. Few cars escaped this graceful attention, and those, mainly because someone happened to be looking at the moment. Meanwhile the cars, fifteen or twenty at a time, passed in through the gates cautiously steering their way amid the throngs of pedestrians who flocked on every ferry till the boat seemed a teeming black hive of humanity. As it steered heavily into the stream it seemed to rock dangerously under its load as it caught the wash of the returning boat, empty and blazing with lights.

As we touched the Long Island shore the hubbub began again, and from the dark bowels of the boat rose the whir of the motors as they were once more being cranked up ready for the road. Away they rolled past the station – the 40 h.p. Mercedes creeping humbly behind the little Ford or Cadillac, which chugged merrily along with its load of laughing passengers.

Reader, it is one thing to order a Borden Avenue beefsteak – it is another thing to eat it. Of all the tough and fibrous commodities known to man, none can compare in combined tenacity and flexibility with this extraordinary and deplorable substance. True, they served potatoes as a palliative with it, but it was a mistake-it should have been dynamite. We did our best with it for five minutes, but never left a mark. Perhaps it was the sudden silence that fell over the restaurant that surprised us, but we looked up. momentarily from our task. Every eye was fixed upon us, but curiously enough, the expression was not one of ribaldry or amusement. We glanced round searchingly. The men were gazing at us with pale, set faces, women were weeping silently, and then it dawned upon us that they had all ordered beefsteaks, too. We rose and stood for one tense moment, while the waiter, with a radiant smile, skipped forward with the bill. We paid it and were turning away when a gentle, dark-haired Southerner at the next table, who had more than once attracted our attention by the refinement of his voice and gestures, fell heavily to the floor in a dead faint.

We knew that water dashed in the face will revive a fainting man, and we threw some Long Island City milk over him. The effect was instantaneous, and he revived. As we gathered about him, curious to learn the cause of his attack, he pointed unsteadily to the beefsteak and murmured, chokingly: „Tracy-Tracy! If I had only known!“ He then handed us his card. He was a traveler in unpuncturable tire bands. We understood, and taking his cold, damp hand in ours, we stole silently away.

He, poor fellow, had missed his chance, but that was, after all, no reason why we should miss our train, and we rushed to the station, fighting our way up the platform and finding seats at last in one of the forward coaches. We need not have been in such a hurry, after all, for it was after a protracted wait that the train finally clanged out of the station on its way to Westbury. The corridors were crowded to the doors. Newsboys shouted early morning editions, containing accounts of the race naturally largely prophetic. Popcorn vendors, chewing gum specialists, and persons identified with the candy and chocolate interests did a land-office trade. A man with a basket of sandwiches which he classified as chicken and ham, met with a cold reception. „Where is the chicken?“ asked one irate customer. „Still running,“ came a voice from the other side of the car. Everybody laughed but the vendor.

In sympathy we purchased two for twenty cents. One we ate, and, in the interests of science, we subsequently submitted the other to an analyst. He instantly detected traces of ham and a small percentage of gallinaceous matter, also. In days like this when even Chicago beef is not immune from suspicion, it is indeed a pleasure to vindicate this humble merchant from the odious charge of falsely representing his wares, and we willingly made the small pecuniary sacrifice involved. That ham and chicken were there was proved beyond a doubt.

Reading matter on the train was plentiful; maps of the course with the various intersecting roads shaded with lines, dots, or dashes, according to their importance were in every hand. There were a dozen guides to the race. You could take your choice from ten cents to twenty-five, and all were „official.“ Never, probably, in their whole history were the names of William K. Vanderbilt and Jefferson DeMont Thompson so taken in vain!

As the train passed slowly through Jamaica it could be seen that that ordinarily peaceful spot was for once having the time of its life. The station was thronged and a line of automobiles extended down the road from the level crossing, waiting for us to pass. As we ran on through the flat lands the mist grew thicker, and the air was cold and raw as we drew into Mineola. Here the fun was beginning with a vengeance, and we followed the rush which was now setting in in earnest for Krug’s Corner, about a mile away.

The little tree-bordered „square“ at Mineola was packed with human beings, a line of cabs touted for patrons, but without much success, for the crowd at this point was not representative of the millionaire element. Across the way the doors of the hotel, a wooden two-story frame building typical of the Long Island village, were blocked by a constant mob of refreshment seekers, and beer flowed within as it never flowed before.

Men propped themselves on chairs on the veranda for a final rest before setting out on foot for Manhasset, Lakeville, Westbury, or some other point on the course. Chauffeurs hurried in and out, begging for water for their motors and beer for themselves. Every small village store had its horde of customers buying up everything they could lay their hands on, or lounging on crates and barrels, smoking and discussing the race-always the race! Further up the street a huge automobile would be found „parked“ in a front garden 12 feet by 10, with its hind wheels barely clearing the sidewalk, and its great nose looking impudently into the little bay window. Dim lights showed from the curtained windows above where some weary automobilist, who had paid a month’s rent for a single room, was wooing a few hours‘ precarious sleep in spite of the pandemonium below.

Everybody seemed to know the way to Krug’s by instinct, and there was little else to guide him, for the night was dark as Erebus and the fog blurred houses, trees, and hedgerows into weird, magnified shapes and made the moving bands of people seem like a procession of ghosts. But everyone was cheerful, not to say hilarious, the racing fever was in their blood and their lungs and spirits were impervious to fog and depression. Every now and then snatches of songs would rise out of the darkness, and voices sounded strangely clear from adjacent fields and roads where other parties were threading their way to the same goal. Behind us two cheerful maniacs chanted a Bacchanalian chorus with a refrain of which no temperance society could approve.

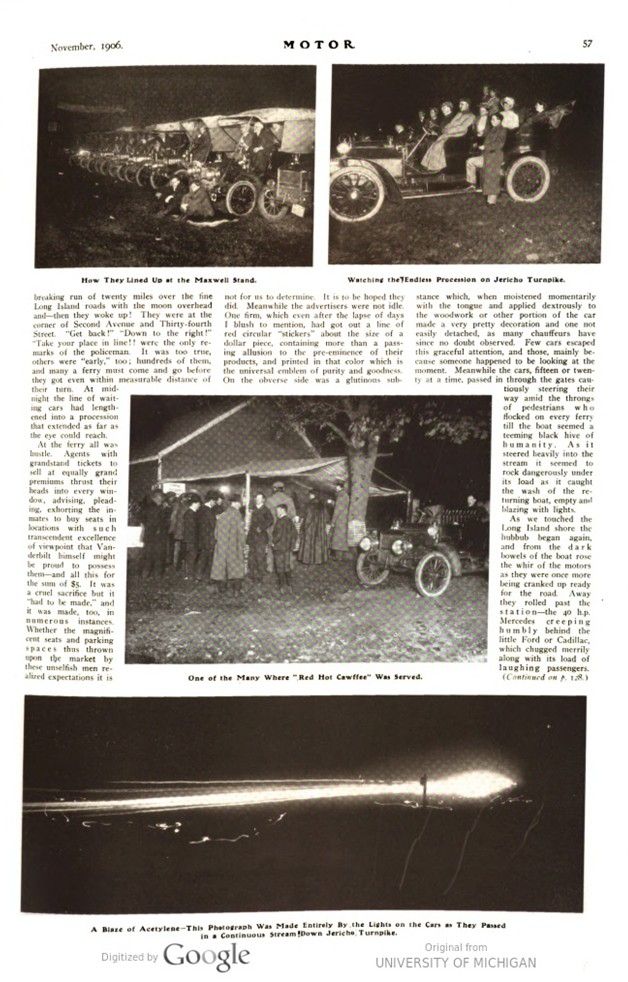

At last Krug’s loomed into view with its crowded tents and stands flaring with lights like a country fair. Here again we struck into the stream of automobilists that we had watched earlier in the night leaving New York. Along the road they came, one after the other, a few feet only between them, often moving at a walking pace, and sometimes stopping altogether in response to a cry far ahead. It was like a crush on Fifth Avenue or Piccadilly, but with the grey background of the lonely fields instead of the glitter and gaiety of the shops and sidewalks. On this point all through the night, probably two thousand cars converged every hour and passed away up the course toward the grandstand at Westbury, or north to Manhasset, Lakeville, or Bulls Head, the great majority choosing the former route.

Over the four miles between Krug’s Corner and the grandstand over 100,000 people were gathered. Near the East Williston crossing another immense stand had been erected, and already hundreds of cars were banked along the grassy sides of the track, flooding the passing crowd that wended its way up the road with the blinding glare from their sleepless acetylene eyes.

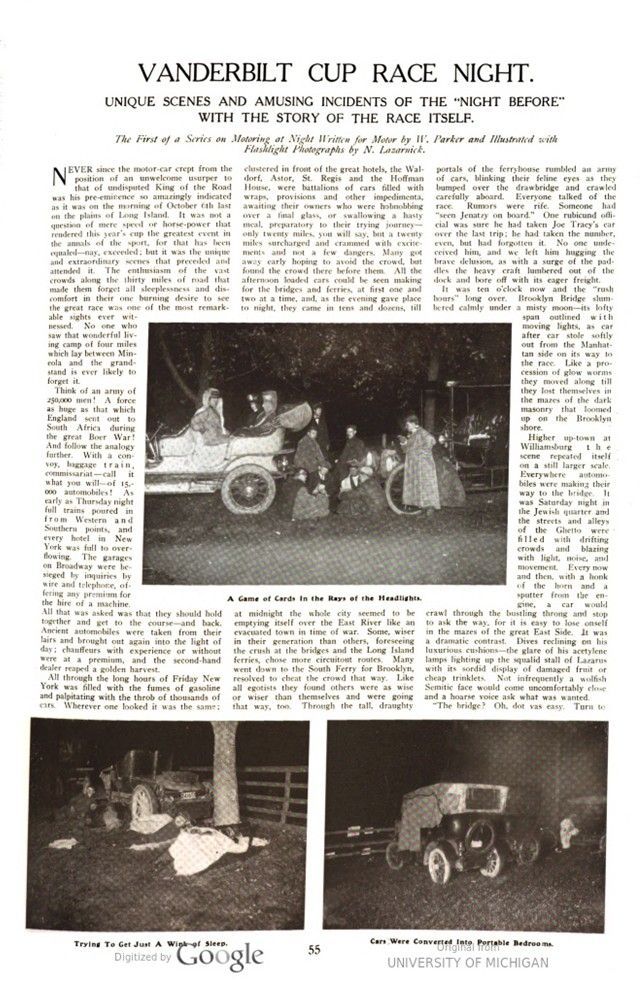

Now and then as one tramped along, sounds of merriment would rise out of the recesses of some covered tonneau, which was converted for the nonce into a miniature hotel; some were supping on the contents of their numerous hampers – others, stretched in awkward attitudes, slept in their cars or on the ground wrapped in rugs. Others, carless and rugless, lay huddled on the chilly ground with a newspaper for a mattress, and the open sky for a coverlet. Here and there under the trees the red glow of a campfire lit up the faces of a merry party; cards came out and flushes fell to full hands and straights surrendered to fours just as they do at home.

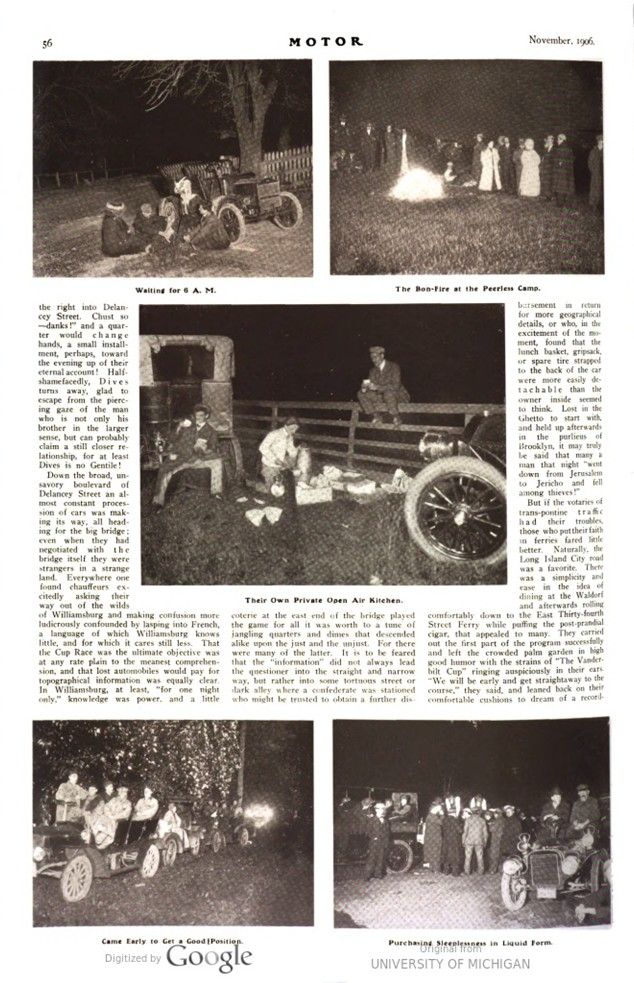

All the byroads were crowded; at these corners small camps collected. At the point where the Old Westbury Road meets the turnpike the tumult was almost as great as at Krug’s, for here was the point that led to the dangerous „Hair-pin Turn,“ a mile to the north. Cars were everywhere, stopping, reversing, turning – drivers asking their way to the „Hair-pin,“ and stopping for a moment at the stalls and refreshment booths where „R-red-hot cawfee“ and the odorous frankfurter seemed the favorite „plat du jour.“

One gaily striped tent which exhibited the cheerful warning, „Great Danger,“ roused that primal instinct within us which leads man ever from the paths of safety and attracted us irresistibly. To drink red hot coffee were to sport with death surely, and we approached the stall with the reckless bravery of the soldier, mixed with that touch of superstitious awe with which one regards a new portent of Nature. That human coffee could attain such a temperature seemed scientifically impossible. We raised our cups slowly and reverently. No deep red glow seemed to emanate from the mixture-on the contrary it looked to us to be of the normal nut-brown shade, but perhaps that was the indifferent light. We placed it to our lips, but there was no calorific shock, no searing of the delicate tissues of the human tongue; we emptied it at a gulp and admired its gentle warmth, approximately that of Chinatown chop suey when not too quickly served.

There was evidently a mystery somewhere – all danger of internal excoriation seemed absent, and thankful for our narrow escape, we went on our way rejoicing, leaving the sum of forty cents in the palm of the conjurer behind the counter. One of our party related how he had once accidentally conducted 500 volts of B. R. T. electricity through his person and so back to the generating station without experiencing any results, and the story was believed. We, out of all that vast army of frail human beings around us were evidently immune; we had proved it again tonight.

Whether it was this consciousness of im- mortality or the after-effects of the mysterious coffee, it is impossible to say, but we lifted up our voices and sang. It did not meet with public approval; various derisive sounds came from under the trees and ribald laughter rose from the passing cars. We concluded it was time to stop.

We were getting into the neighborhood of the grandstand now, and the cars and crowds were thicker than ever. Long wire fences had been erected to keep the public off the track for half a mile on either side. The hour of five struck, but already the official stand, with its huge scoring board looming blackly against the sky, was filled to overflowing. Officials rushed about directing the passing cars to their final destinations, and telephone messages were coming in from all parts of the course. There was not a dull moment in the last waiting hour. Friends turned up in the most unexpected places. Experts who had seen all the great races at home and abroad, exchanged notes and voted this to be the greatest of all. Overcoated and muffled men dived into the recesses of their pockets and looked up the tickets and numbers of their boxes by the light of their lamps, for the dawn had not yet appeared. At last, as six o’clock approached, the long line of cars began to thin, and in the growing light one could see patrols down the line clearing the course and turning the late- coming cars into places of safety. Now the last headlight had loomed up the road and passed hurriedly amid a shouting of orders to take its place in the great parking ground of the Automobile Club. The crowds hurried to their places, clustering on hedges, in trees, climbing even the tall telegraph poles and clinging precariously to the crosstrees.

It was six o’clock now, and a hush of excitement fell over the crowd, broken by a sudden roar from nearby that told that one of the great speed machines, lurking like hidden lions in the gloom, was clearing its iron throat for action. One by one they got under power, their drivers and mechanicians alert and busy giving a last touch to a tire or testing the ignition, and making all connections finally secure, against the storm and stress of that desperate rush of three hundred miles.

They looked cool and composed – these men – cooler than many of the spectators, as they stood idly chatting with their friends, or puffing comfortably at a cigar, though death would face them many times in the next six hours.

There were a few moments of tense suspense, when a voice, magnified out of all humanity by the megaphone, announced a fifteen-minute delay. Night had as yet scarcely surrendered, and the mist hung heavily over the dark road, which looked doubly black under its coat of oil. Le Blon, on the 115 h. p. Thomas car, was the first to face the line. Full bearded and dressed in close-fitting khaki, he made a grim and determined figure as he took advantage of the few moments‘ delay to dismount and take a last look at his machine. As the moment for the start came, the car got under power, snorting fiercely and shooting tongues of blue flame from its open exhausts. A moment later the tape was stretched behind his driving wheels, and Wagner, the starter, with the word „go,“ and a friendly clap on the back which meant „now“ and „bon voyage“ in one, sent Le Blon on his fiery way. Then Heath, on the Panhard, exchanging a last cheery word with Jenatzy, took his place and shot away on the stroke of 60 seconds. Jenatzy came next, and as Lancia, the smiling Italian giant got away fourth on his FIAT, with a noise like a battery of big guns, cheers and waving of hats and handkerchiefs rose from the lines of spectators.

Then followed the Frayer-Miller, the Hotchkiss, Luttgen in the second Mercedes, Nazarro on a FIAT, and then Tracy, the American champion, who received a great ovation as he got away in fine style on the Locomobile. No. 10, the 100 h. p. Darracq, driven by Wagner, came next, and the „wise ones“ in the crowd, watching his splendid start, freely prophesied that he would not be far away at the finish. No. 11, the third Mercedes, to be driven by Mr. Foxhall Keene, did not start. A concession to superstition was made in eliminating „Thirteen,“ and the American car, the 60 h. p. Haynes, appeared on the program as No. 14. Next in order were the Clement-Bayard, driven by Clement, and Dr. Weilschott’s 120 h. p. FIAT; Christie, on his 50 h. p. „Christie,“ – a long, low, light, rakish looking machine, driven by the front wheels – came next. After him. Duray, on the DeDietrich, and Fabry, on the 120 h. p. Itala last. All left the tape to the moment, and Fabry started punctually at 6.17.

Day had fairly come now, and the excitement of the start over, people had time to settle themselves comfortably in their seats and watch the newcomers‘ arrival. A chatter arose from the grandstand as „Society“ began to throw off its wraps and veils and discover its neighbor’s identity. Friends hilariously greeted friends who had not met since they swam together in the surf at Bailey’s Beach, at Newport, or played the winner on the grandstand at Saratoga. And yet the time was half-past six on a raw October morning. and they were perched on a bleak grandstand ten miles from anywhere. Still, true to its traditions, „the 400“ was „en grand tenue.“ Dainty women stepped from their covered automobiles in the latest, creations from Fifth Avenue and Paris, and more than one heavy diamond necklace sparkled in the dim morning light.

Some had come from long distances by train or car; a multitude had driven in their own automobiles from New York, and had not tasted sleep, except what could be found in the tonneau of a traveling car. Another contingent had flooded the huge Garden City Hotel, five miles away over the plains, and tried to woo sleep in its packed bedrooms, or had supped and talked in the crowded dining-rooms and corridors, till four o’clock, and breakfast served by the hurrying waiters, apprised them of the fact that the night was gone; but all looked radiant as if French maids and coiffeurs had just turned them out perfect „au bout des ongles“ (en: at the tips of the nails) for a Madison Square Garden Horse Show or a ball at Sherry’s.

And truly they had not come out into the wilderness to see nothing. In the grim trial of strength between the great steel racers with their iron-nerved masters there is a fascination that appeals to the daintiest dame as well as to the strongest man-and all felt it that morning. Death, swift and terrible, lurked in every mile of that dark ribbon of oiled road that stretched away on either hand into the dim distance like a great sleeping snake.

The minutes rolled by. The seventeen huge monsters were miles away now-was fate being kind to them on that distant „Hair-pin“ turn or the „dip of death“ that lay away to the northwest over the low mist-clad hills? Everyone wondered. „No. 16 has had an accident. Out of the race,“ came from the megaphone with startling suddenness. Dr. Weilschott had broken the steering gear of his FIAT and had gone over an embankment. „Uninjured, but chauffeur hurt,“ was the answer to anxious queries, and, relieved, the crowd turned to the race again. The leaders were due now, and every eye was strained down the course in the direction of Mineola.

The distant sound of a bugle rose on the air, and, with the cry „Car coming!“ the first racer hove in sight-a dark speck which grew bigger and bigger, till, with a rattle and roar it hurled itself past the stands and disappeared like a flash. Jenatzy had got into first place and was going like the wind. Another roar and flash and Lancia was gone, hot on his trail. Then the Hotchkiss passed with a bang. The Thomas should be next, or the Locomobile, or Heath in the Panhard, who had started second, but all are in for a surprise when a low-built, light blue car sweeps into view. It is the Darracq, with Wagner at the wheel, who has passed six competitors on his first round and is driving with marvelous speed and skill; already he looks like a winner, and the wise ones note him down as dangerous.

It is a dramatic round and a fit opening for the great race, for much has happened in that brief half hour. Tracy has had trouble with his tires and has lost three places. Le Blon, on No. 1, has lost ground heavily and is now at the tail end of the hunt, but drives gamely – nay, desperately. Duray is going well and has crept into eleventh place, though he started second last. He is evidently to be counted with.

Thus, it goes on; lap after lap is covered with varying fortunes, and strength and stamina of men and machines are beginning to tell. Tracy has been unfortunate, and all the drivers complain of the dangerous crowds that surge on to the course at every point, breaking down wire barriers, and flooding over the roads till the 700 officials and special constables are at their wits‘ end. One man is hurled to instant death by the wheels of the Hotchkiss, and the Locomobile has struck and fatally injured a boy. As the news filters in from all parts of the course the accounts are the same. There is a moment of intense excitement when Tracy stops before the grandstand and shouts to the officials that all will be over, or some desperate action must be taken to avoid catastrophe. Mr. Vanderbilt jumps quickly into his big Mercedes. Instantly a warning is sent by telephone to every part of the course that unless the roads are cleared the race will be stopped. In little more than half an hour he is back, and 250,000 people have seen the gray car without a number and know the reason why it is there. Pickets, flagmen and deputy sheriffs go to work like madmen; crowds are pushed and beaten back with desperate determination, and the course is cleared as far as human energy can do it.

The race goes on; the long morning passes into day and lap after lap is added till the end draws near. Nothing can control the crowds now. All unconscious of the danger and growing familiarized with the bugle call and the cry „Car coming!“ they take the most incredible risks; at the last moment they save themselves as if by a miracle, hurrying and swaying just out of reach as a car thunders by. A swerve of a foot, an instant’s faltering of eye or hand on the part of the driver, and a fearful tragedy must result. But every nerve is being strained now to push the people back.

Wagner, going well as ever, has shot into the straight for the last round, leading Lancia by six minutes, with Duray close behind, and the indomitable Jenatzy in fourth place. Driving with magnificent élan, Wagner speeds away on his last lap. Everyone feels that with his commanding lead he must win the race. Five minutes pass; some of the laggards, still driving desperately, are up with, and have passed the leaders, but the crowd knows the meaning of it. They are a lap behind, and the applause is not for them. Ten, fifteen minutes have passed-in another quarter of an hour all will be over; already some of the crowd on the stands are beginning to rise and get away before the crush begins; but the most dramatic moment is yet to come.

Suddenly the megaphone strikes on startled ears. „No. 10, tire trouble at Bulls Head!“ It is Wagner, whose victory has been snatched from his grasp at the eleventh hour. „Out of the race!“ comes from some official source, and a stunned silence falls upon the crowd. It is Lancia now, and much as the crowd admire him, they are jealous that an accident should give him the laurels so bravely earned by another. The crowds are all excitement, breaking all bounds, they surge out upon the course to see Lancia finish. He does not disappoint them. The bugle blows in the distance and round the curve under the distant trees the swarming people part into a living lane as the dark speck comes into view. With every ounce of power in the cylinders the great FIAT thunders up the straight amid a roar of cheers. Without a touch on the wheel, straight as a huge projectile, it hurls itself past the line and dashes on with furious momentum into the flying, cheering crowds beyond.

But the race is not yet won. Duray has twelve minutes in hand and may claim the prize yet. A minute, two minutes pass when the unmistakable sound of the bugle echoes in the distance. Everyone listens and wonders. Down the course there is a long thunder of cheers, field glasses tremble in many a nervous hand, all concentrated on the minute, moving object half a mile away. Someone descries the number, and it is not Duray’s. A moment later the crowd is shouting, cheering, and waving hats and handkerchiefs in a delirium of surprise and delight, for it is gallant Wagner still at the wheel.

Truly he had made good use of those six golden minutes. Four of them had already passed when the last bolt was feverishly clinched on his new tire, and he dashed away on the sixteen fateful miles that lay between him and the distant stand at Westbury. Fifteen minutes later, with every steel nerve strained to the bursting point of speed, he hurled the great Darracq across the finish line, 4 hrs. 50 min. 10 sec. from the start, the winner of the Vanderbilt Cup.

Altogether it was a memorable race. No such crowd, it is safe to say, ever witnessed a motor race in this or any other country. It is computed that New York alone contributed some 200,000 persons toward the immense total, and 15,000 cars at least were massed round the course of thirty miles.

Photo captions.

Page 55.

A Game of Cards In the Rays of the Headlights. Trying To Get Just A Wink of Sleep. Cars Were Converted into Portable Bedrooms.

Page 56.

Waiting for 6 A. M. – The Bon-Fire at the Peerless Camp.

Their Own Private Open Air Kitchen.

Came Early to Get a Good Position. – Purchasing Sleeplessness in Liquid Form.

Page 57.

How They Lined Up at the Maxwell Stand.

Watching the Endless Procession on Jericho Turnpike.

One of the Many Where „Red Hot Cawffee“ Was Served.

A Blaze of Acetylene-This Photograph Was Made Entirely by the Lights on the Cars as They Passed in a Continuous Stream! Down Jericho Turnpike.