The 1909 Indianapolis Racing event was the very first of it’s kind on the Indianapolis Speedway, with a large number short races divided over three days in August. Alas, it was marred by severe accidents, taking the lives of seven drivers, mechanics and spectators. Race results now were not on the scope anymore, instead a huge discussion whether this kind of speed carnivals should be forbidden. Later that year, the yard was bricked, thereby annihilating the main cause of these accidents.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

The Motor World, Vol. XX, No. 22, August 26, 1909

UNDER SPELL OF SPEED

Indianapolis Inaugurates Colossal Motordrome with Three Days of Spectacular Racing

Crowds Thrilled by Fast Events – Tragedies Mar Opening and Closing Days.

After months of ceaseless toil and worry on the plot which once was a field of golden grain, the dreams and hopes of the builders of the Indianapolis (Ind.) Motor Speedway were realized on its inauguration on Thursday last, 19th inst. Three days were devoted to the speed carnival on the colossal ellipse, which marks a new era in American track racing.

It was a most significant event to the industry, ushering in the first American attempt to emulate the British project which has been experiencing none too hopeful success at Brooklands for the past three years.

Despite the great amount of labor and pains which had been expended in constructing it, the track surface proved to be totally unfit for racing purposes. As was predicted by many who had examined it beforehand, the rough surface and unlaid dust were almost too great a tax on the skill of the drivers. Indirectly, the poor condition of the course may be considered responsible for the loss of no less than seven lives – a most unfortunate and regrettable blot on what was in other respects one of the biggest occasions American motorists ever have been privileged to witness. Certainly the condition of the course prevented the annexation of the long string of records which had been so hopefully foretold, though matters were materially improved when the management of the track was forced to mend them on penalty of immediate outlawry in the event of further negligence.

All roads led to the motordrome on Thursday, for the opening which was set for 12 o’clock noon. Everyone of the 36 automobile factories in the state, 10 of which are located in Indianapolis itself, sent large delegations. Chicago contributed over 500 spectators, the Stoddard-Dayton Company of Dayton, O., hired a special train and filled it with their employes, and from far and near the crowds came. It was a red letter day in the his- tory of Indianapolis, and the God of Speed reigned supreme.

Over sixty entries were received for the meet, and nineteen times during the three days the starter acted in his official role. Among the competing cars there was a liberal sprinkling of Indianapolis machines, and the excellent showing made by the home product is noteworthy. Chief among the Indianapolis cars to win laurels was the National. It was a consistent performer on all three days, and made the best showing of its career since the establishment of 24 hours record four years ago, which, oddly enough, was made in Indianapolis. The Marmon was another local contender which performed creditably.

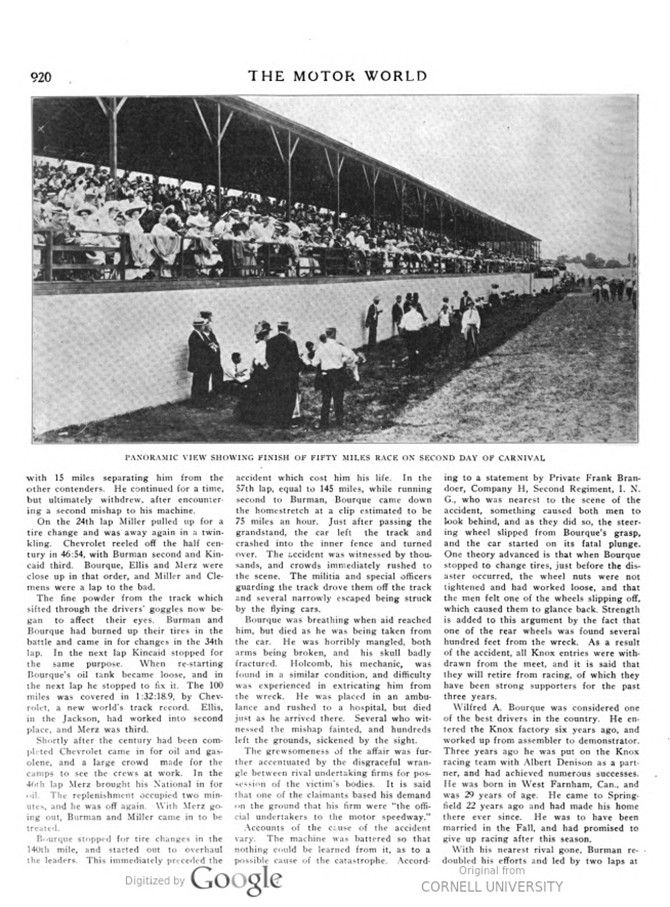

When the managerial mechanism was set in motion at noon Thursday by Starter Wagner, over 12,000 people were in the stands. Brilliantly attired society folks, farmers, motorists, and the leisure class, gathered from all sections of the country, rubbed elbows. To the Stoddard-Dayton belongs the honor of winning the opening race of the meet, five miles, for cars with a piston displacement between 161 and 230 cubic inches. Five cars lined up for the word, and at the very outset the Stoddard-Dayton cars, driven by Wright and Schweitzer, showed winning form. At the bell Schweitzer led his team mate by a slight margin and maintained his position to the finish, winning in 5:13 2/5.

The next event, 10 miles for cars between 231 and 300 cubic inches piston displacement, brought out eight starters. Chevrolet took the lead at the start and outran the field, winning by over a mile, in 8:56. Strang and Burman were placed in that order, and Stillman, in a Marmon, landed fourth place. The time is a new American record.

A promising array faced the starter for the five miles for cars in the 301-450 displacement class. They supplied plenty of action all the way, and after one of the closest and hottest fights ever seen on a track, Bourque, in a Knox, defeated Burman, in a Buick, by 9-10 of a second, in 4:452. It was a wheel to wheel struggle for the entire distance, neither giving way to the other, and the best man won. Although he did not know it, it was to be Bourque’s last victory, and a well deserved one. Chevrolet annexed third place.

The ten miles free-for-all handicap brought out the largest field of the day, 22 cars responding to the word. Home talent won, Harry Stillman, in a Marmon, with an allowance of 1:45, finishing first in 8:22. All the local cars were favorites with the crowd, and Stillman received an ovation. Lynch, piloting a Jackson, was given 1:30 on the honor men, and took second, barely beating out Aitken, in a National, who had 20 seconds. Aitken drove a splendid race, and moved up from ninth place in the second lap, to third at the finish. After several years of barnstorming the county fairs, and exhibitions in the Middle West, Barney Oldfield came out under the spot light and got into fast company. It was the first time he has sworn by a foreign car, and he drove his latest love, the Benz, which Bruce-Brown campaigned so successfully in the East in the Spring. Barney was sent away for the mile track record of 51, made by De Palma, and put a bad dent in the old figures. He was clocked in 0:43 1-10. This was done on a straight-away stretch, however, while in De Palma’s case the track included two turns.

These preliminary brushes whetted the crowd’s appetite for the big feast of the day, the 250 miles Prest-O-Lite trophy race, which, incidentally, was to mark the passing of one of the foremost American drivers in the first tragedy of the meet. Nine cars were sent away on the long journey, as follows: Bourque, in a Knox; Merz and Kincaid, National; Miller and Clemens, Stoddard-Dayton; Burman, Strang and Chevrolet, Buick; and Ellis in a Jackson.

From the very start the fight was on. Chevrolet made the running, and Burman was at his rear wheels. These two started to burn things up and gradually opened a gap between them and the rest of the field. The Frenchman held the lead until the 15th lap, or 36th mile, when Burman wrested the coveted honor from his mate. Meanwhile the rest of the field were struggling to close the gap which separated them from the leaders. Burman’s occupancy of the leadership was short lived, for Chevro-et got his second wind and went by in the 17th lap. By this time Kincaid had worked his National into third place, and was close on Burman’s heels.

Accidents commenced early in the race, when Strang’s Buick caught fire, and blazed merrily for a time. The track fire brigade finally quenched the flames, but Strang was ruled out for receiving outside assistance in violation of the rules. After a warm argument the judges reconsidered their decision and allowed him to return to the track with 15 miles separating him from the other contenders. He continued for a time, but ultimately withdrew, after encountering a second mishap to his machine.

On the 24th lap Miller pulled up for a tire change and was away again in a twinkling. Chevrolet reeled off the half century in 46:54, with Burman second and Kincaid third. Bourque, Ellis and Merz were close up in that order, and Miller and Clemens were a lap to the bad. The fine powder from the track which sifted through the drivers‘ goggles now began to affect their eyes. Burman and Bourque had burned up their tires in the battle and came in for changes in the 34th lap. In the next lap Kincaid stopped for the same purpose. When re-starting Bourque’s oil tank became loose, and in the next lap he stopped to fix it. The 100 miles was covered in 1:32:18.9, by Chevrolet, a new world’s track record. Ellis, in the Jackson, had worked into second place, and Merz was third.

Shortly after the century had been completed Chevrolet came in for oil and gasolene, and a large crowd made for the camps to see the crews at work. In the 46th lap Merz brought his National in for oil. The replenishment occupied two minutes, and he was off again. With Merz going out, Burman and Miller came in to be treated.

Bourque stopped for tire changes in the 140th mile, and started out to overhaul the leaders. This immediately preceded the accident which cost him his life. In the 57th lap, equal to 145 miles, while running second to Burman, Bourque came down the homestretch at a clip estimated to be 75 miles an hour. Just after passing the grandstand, the car left the track and crashed into the inner fence and turned over. The accident was witnessed by thousands, and crowds immediately rushed to the scene. The militia and special officers guarding the track drove them off the track and several narrowly escaped being struck by the flying cars.

Bourque was breathing when aid reached him, but died as he was being taken from the car. He was horribly mangled, both arms being broken, and his skull badly fractured. Holcomb, his mechanic, was found in a similar condition, and difficulty was experienced in extricating him from the wreck. He was placed in an ambulance and rushed to a hospital but died just as he arrived there. Several who witnessed the mishap fainted, and hundreds left the grounds, sickened by the sight.

The grewsomeness of the affair was further accentuated by the disgraceful wrangle between rival undertaking firms for possession of the victim’s bodies. It is said that one of the claimants based his demand on the ground that his firm were „the official undertakers to the motor speedway.“

Accounts of the cause of the accident vary. The machine was battered so that nothing could be learned from it, as to a possible cause of the catastrophe. According to a statement by Private Frank Brandoer, Company H, Second Regiment, I. N. G., who was nearest to the scene of the accident, something caused both men to look behind, and as they did so, the steering wheel slipped from Bourque’s grasp, and the car started on its fatal plunge. One theory advanced is that when Bourque stopped to change tires, just before the disaster occurred, the wheel nuts were not tightened and had worked loose, and that the men felt one of the wheels slipping off, which caused them to glance back. Strength is added to this argument by the fact that one of the rear wheels was found several hundred feet from the wreck. As a result of the accident, all Knox entries were withdrawn from the meet, and it is said that they will retire from racing, of which they have been strong supporters for the past three years.

Wilfred A. Bourque was considered one of the best drivers in the country. He entered the Knox factory six years ago and worked up from assembler to demonstrator. Three years ago, he was put on the Knox racing team with Albert Denison as a partner and had achieved numerous successes. He was born in West Farnham, Can., and was 29 years of age. He came to Springfield 22 years ago and had made his home there ever since. He was to have been married in the Fall and had promised to give up racing after this season.

With his nearest rival gone, Burman redoubled his efforts and led by two laps at 160 miles. Six cars still remained in the race. Kincaid, in the National, was sec- ond, and Ellis, in the Jackson, third. Shortly after Bourque’s accident, Chevrolet was forced to withdraw, his eyes being in such bad shape from the tar and dust that it was considered dangerous to allow him to continue. He was taken to the hospital and collapsed as he passed the dead bodies of his two former rivals.

Burman stopped for water in the 83d lap and Ellis took advantage of his rival’s halt, and with a grand spurt, took the lead. Ellis was not long the leader, for his mechanic fainted from the strain and had to be replaced, and then ignition troubles set in. His eyes also began to be affected by the tar and dust and he stopped to have them treated. During the time he was off the track, the engine quit and efforts to restart it proved fruitless. With victory snatched from his grasp, by a dead engine, Ellis fainted and was taken to the hospital. Lynch, his successor, made desperate efforts to get the car going, but they were of no avail and he was forced to see his rivals gradually get beyond his reach.

Burman again took the lead from Clemens in his Stoddard-Dayton, and held it to the end. Kincaid, in the National, was third. Burman’s time was 4:38:57 2/5, which was slow, owing to the many mishaps.

As a result of the fatalities President Speare, of the A. A. A., ordered the management to oil and tar the track thoroughly and remove all dangerous ruts before any more races were held, threatening to withdraw the sanction of the track otherwise.

A Day of Records, but no Accidents.

There was a plentiful smashing of records on the second day, and not an accident occurred to detract from the achievements of the afternoon. Complying with the orders of the A. A. A., the management put a large force of men at work on the track at the conclusion of Thursday’s racing, and by Friday noon it was pronounced in much better shape than on the opening day. A much larger crowd was present, both stands being filled, and the number of spectators was rated at over 18,000. The parking places were well filled with cars.

The opening number on the card was an attempt to lower Oldfield’s mile record of 0:43 1-10, made on the first day. Driving his Benz, Barney registered 0:43, one fifth of a second slower than the record. Then De Palma went after it with Hearne’s Fiat, but the best he could do was 0:48 3/5. It was said that the Fiat Cyclone was so light that it could not be held down on the rough track, and therefore was not used. Zengle, in a Chadwick, negotiated the mile in 0:49 3-10. As usual, Christie’s latest creation balked at the critical moment, so Old- field’s record of the previous day was not altered.

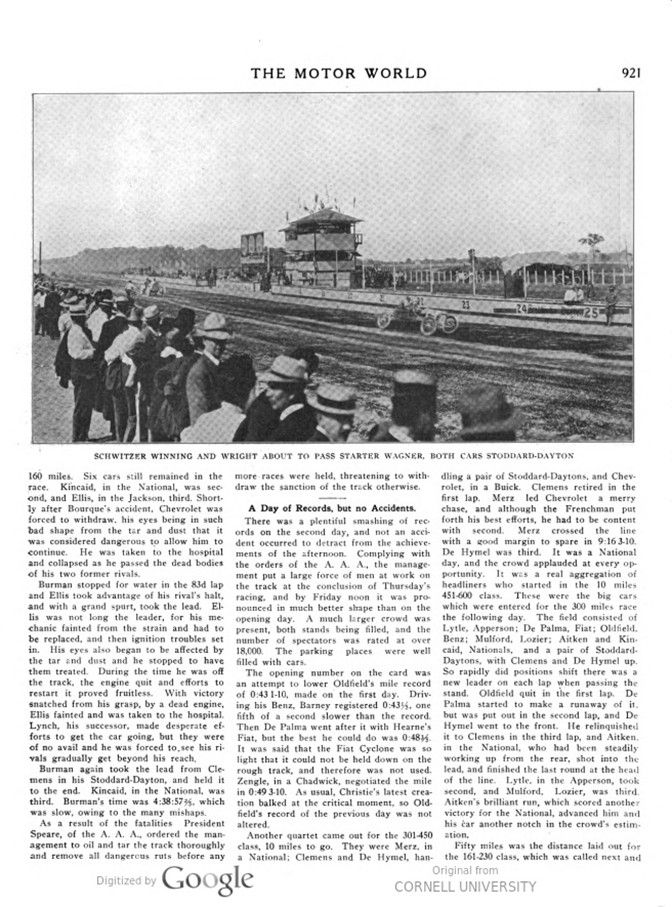

Another quartet came out for the 301-450 class, 10 miles to go. They were Merz, in a National; Clemens and De Hymel, handling a pair of Stoddard-Daytons, and Chevrolet, in a Buick. Clemens retired in the first lap. Merz led Chevrolet a merry chase, and although the Frenchman put forth his best efforts, he had to be content with second. Merz crossed the line with a good margin to spare in 9:16 3-10. De Hymel was third. It was a National day, and the crowd applauded at every opportunity. It was a real aggregation of headliners who started in the 10 miles 451-600 class. These were the big cars which were entered for the 300 miles race the following day. The field consisted of Lytle, Apperson; De Palma, Fiat; Oldfield, Benz; Mulford, Lozier; Aitken and Kincaid, Nationals, and a pair of Stoddard-Daytons, with Clemens and De Hymel up. So rapidly did positions shift there was a new leader on each lap when passing the stand. Oldfield quit in the first lap. De Palma started to make a runaway of it. but was put out in the second lap, and De Hymel went to the front. He relinquished it to Clemens in the third lap, and Aitken, in the National, who had been steadily working up from the rear, shot into the lead, and finished the last round at the head of the line. Lytle, in the Apperson, took second, and Mulford, Lozier, was third. Aitken’s brilliant run, which scored another victory for the National, advanced him and his car another notch in the crowd’s estimation.

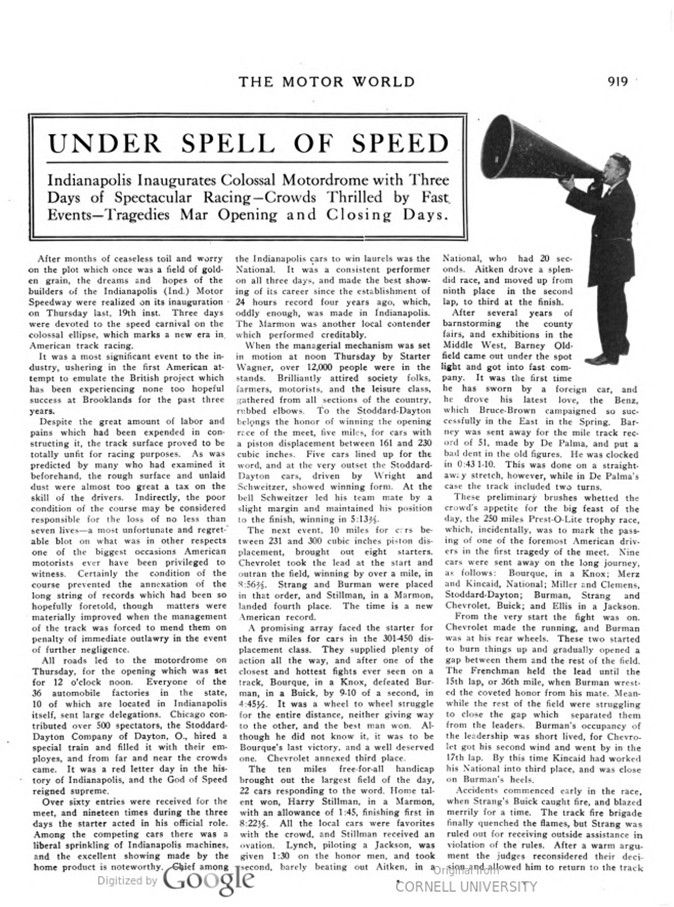

Fifty miles was the distance laid out for the 161-230 class, which was called next and five elected to try it. The quintet consisted of a pair each of Stoddard-Daytons and Buicks and a lone Velie. The Stoddard-Daytons had a walkover. De Witt and Ryall quit early, and Merritt, in the Velie, retired at 10 miles. Then Schwitzer, who was leading in a Stoddard-Dayton, turned the lead over to his partner, Wright, and they finished in that order. In the 10 miles free-for-all, Zengle, in a Chadwick, rode rings around the field and set up a new world’s record of 8:23 1/2.

Nationals scored again in the five miles free-for-all handicap, Merz being the victorious pilot, and his team mate, Aitken, was but 1-10 of a second behind. It was the closest race of the day, thirteen cars starting. Merz had twenty seconds allowance on the honor men, while Aitken was given ten seconds, so he really made the best time. Merz’s figures were 4:25.

With the short distance events part of history, the feature of the day was put on, one hundred miles for the G & J trophy. Seven answered to their names, as follows: Strang, De Witt and Chevrolet, the Buick trio; Monsen and Stutz, in the Marions, and Stillman and Harroun, the Marmon team. At the start Strang got the pole, and immediately started to run away from the field. On his first lap he led by a comfortable margin, and was steadily widening the gap. The Marions soon were last, and Chevrolet pushed up and tried to oust his mate from the leadership, but was fought off. Meanwhile the Marmon team showed plenty of speed, and forced the Buicks to go the limit to stay in front. Steadily as clockwork Strang was burning up the miles, and it seemed as if he had shaken off the hoodoo that has beset him so constantly in the past. Records began to fall and still he was constantly increasing his lead. At the half century mark he led his team mate and nearest competitor, De Witt, by two laps. New figures were hung up for the 50 miles, 46:0435. Without making a stop, Strang reeled off the century in 1:32:482. This was a new record, but the judges would not allow it to stand, as Chevrolet had covered the first hundred miles in the 250 miles race on the previous day in 1:32:18 9-10. Although Chevrolet’s time is intermediate and he did not finish the race, his time was announced as stand- ing as the record.

———

Third Day Ends Disastrously.

Twenty thousand people, the largest crowd of the meet, witnessed the breaking of more records on Saturday, the final day of the races. Along the homestretch private cars were packed in a row over half a mile in length. First on the card was the kilometer trials. Oldfield again showed the way, registering 0:26 1/3. Christie managed to get his car going and it completed the distance without breaking down, which was in the nature of a surprise. He was clocked in 0:28 7-10, and Zengel, in a Chadwick, rung up 0:29 9-10. The kilometer record is 0:19%, made by Chevrolet at Ormond, Fla., in 1906, but Oldfield’s figures stand for the distance on a circular track.

A wolf got into the sheepfold in the ten miles for the American amateur championship, when Ryall, of the Buick crew, who poses as a Simon pure, although commonly supposed to be a paid driver, had the effrontery to line up with the field. The other „legitimates“ were Hearne, in the Fiat; Greiner, in a Thomas, and Cameron, in a Stearns. The first lap saw the passing of Cameron, and Greiner went out in the next round. Ryall led in the second and third circuits, when Hearne went to the front and saved the day for the real amateurs by winning in 9:44 3-10.

The next offering was the twenty-five miles free-for-all, which was one of the best races of the meet. It was an all-star-cast that took the word, Oldfield. De Palma and Zengel. Barney was primed for action, and drew a lead of 50 yards on Zengel at the start. Zengel fell back further and De Palma moved up to second place. Meanwhile Barney was going great guns, and records were falling like leaves in a windstorm. The figures, 21:21 7-10, are new world’s records, as also are the times for 5, 10, 15 and 20 miles.

By his victory, Oldfield is entitled to wear the Remy Brassard offered by the Remy Magneto Co., of Anderson, Ind., and will receive, it is said $75 per week for every week that he holds it against all comers. He also has a good grip on the gold plated car offered by the Overland Automobile Co. for the fastest mile of the year made on the speedway. His mark of 0:43 1-10 was not eclipsed during the meet, he himself coming nearest to it, and it is probable that no other car in the country today can alter his figures.

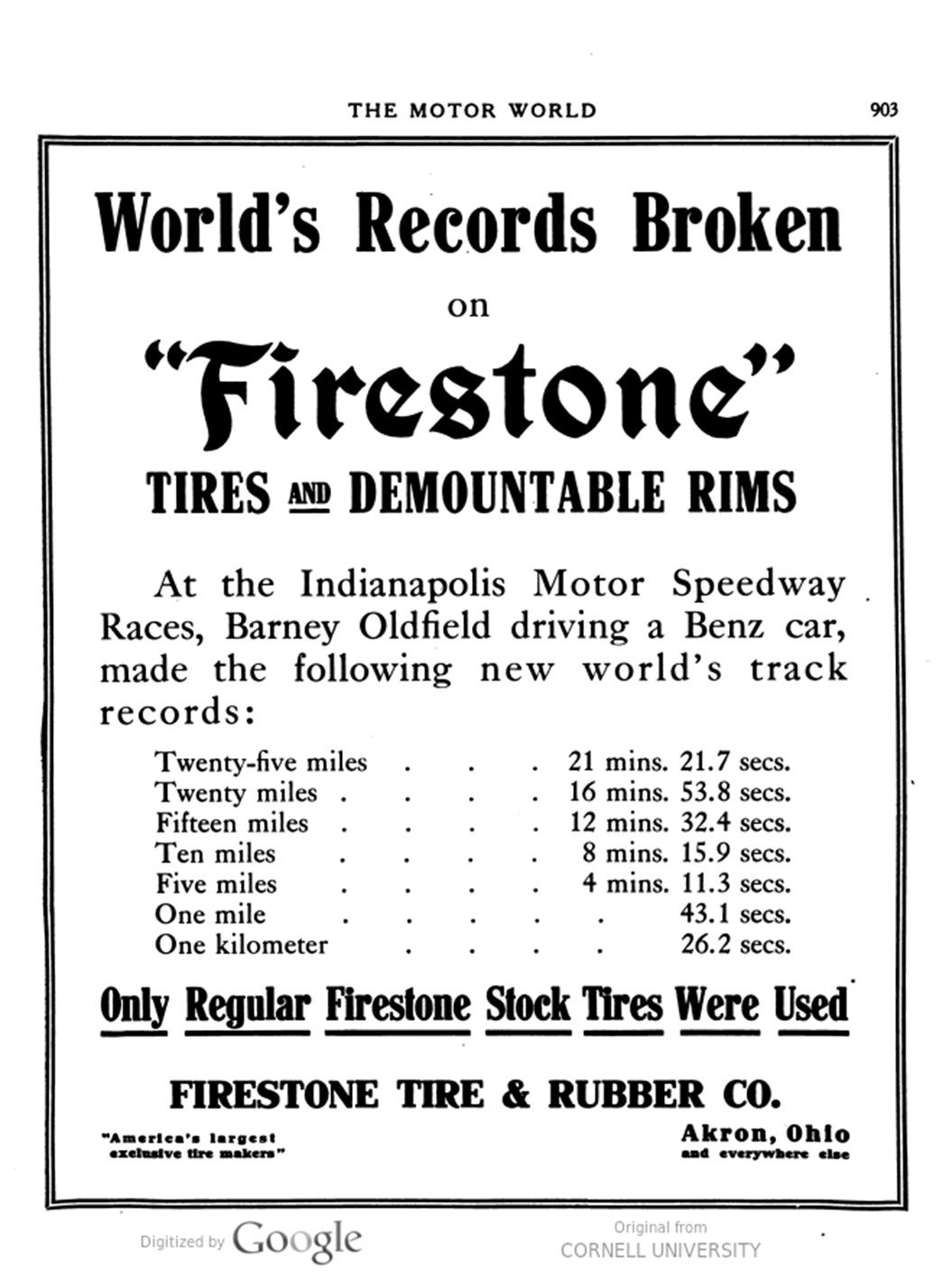

Next came the grand finale, and the biggest feature of the meet, the 300 miles race for the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. trophy. Like its counterpart on the opening day, it was marked by fatalities, and finally was brought to an abrupt end in the 235th mile.

When the starting gun sent them away on their long journey, which was to be marked with disaster, there was much jockeying for position, and at the completion of the first lap Aitken, in a National, was at the head of the procession. With such a large field and the increased chances of accidents the drivers took no risks in crowding and the field was well strung out. Aitkin led at the twenty-five mile post, and was still in front at the half century, with 44:21. Lytle was second and De Witt third. Shortly after completing the fifty miles Lytle’s steering gear broke on the south turn and the car slid down the incline and buried its nose into the soft dirt. Lytle and his mechanic escaped injury.

Aitken still was leading at the century mark, with 1:31:41, a new record for the distance. His average was 65 miles an hour. However, in the 150th mile he cracked a cylinder and retired, after having made a brilliant run from the start. The dust and heat began to affect many of the crews, and the ambulances were kept busy.

When Aitken’s car gave out his mechanic, Kellum, broke down and wept at being unable to continue. Shortly after Merz’s car stopped on the back stretch, with battery trouble. The mechanician, Robert Lyne. like Heidippides, of Marathon fame, ran across the infield and after gasping that he wanted a battery, collapsed. Kellum, seizing the opportunity to get back in the contest, grabbed a battery and scrambled across the field to Merz’s relief. After some delay they got the car going again, and started to make up their lost ground. By this time the track was very rough and the cars were swerving badly. As they passed the stand the first time Kellum waved a salute, and the local favorites were cheered by the crowd for their pluck. They began to overhaul the field steadily, and other cars were dropping out at frequent intervals, which strengthened their chances for getting up front.

Strang dropped out at 147 miles and Burman, who was leading, followed soon after, with cracked cylinder heads. Lynch, in the Jackson, was the leader at 150 miles, in 2:39:34 1-10. De Palma had moved up to second, and Stillman was third. Merz, in the National, was in fourth place, and was going famously when on the back stretch the right front tire burst. At the same instant the car crossed a bridge which spans a small stream that courses across the track, swerved into the outer fence, crashing through it and into the crowd, and turned turtle, pinning Merz beneath it. Kellum was hurled against the fence with terrific force as the car struck, and his head hit a post. He was picked up unconscious and rushed to a hospital, but died in an hour. Two of the spectators, Homer Jolleffs, of Trafalgar, and James West, of Indianapolis, who were on the rail watching the race, were speared by the car in its plunge and were horribly bruised and mangled, being killed instantly. By a miracle Merz escaped serious injury, receiving but a slight scratch, and even turned off the ignition switch, while under the wreck. Henry Tapking, a spectator, sustained probably fatal injuries.

Meanwhile the race continued, but the spectators had lost interest, owing to the catastrophe. The race came to an abrupt termination when in the 235th miles Keene, in a Marmon, while in third place and traveling in rocket fashion skidded and crashed into the fence near the scene of the previous accident. He received several cuts and his mechanic sustained a slight fracture of the skull, and the officials immediately called the race off, deciding that enough casualties had occurred. At a coroner’s inquiry, held subsequently, the earlier fatalities were ascribed to the roughness of the course.

First Day – Thursday.

Five miles, for stock chassis, 161 to 230 cubic inches piston displacement – Won by Schwitzer, Stoddard-Dayton; second, Wright, Stoddard-Dayton; third, De Witt,“ Buick. Time, 5:13 2/3.

Ten miles, for stock chassis, 231 to 300 cubic inches piston displacement – Won by Chevrolet, Buick; second, Strang. Buick; third, Burman, Buick. Time, 8:55.

Five miles, for stock chassis, 301 to 450 cubic inches piston displacement – Won by Bourque, Knox; second, Burman, Buick; third, Chevrolet, Buick. Time, 4:452.

Ten miles, free-for-all, handicap – Won by Stillman, Marmon (1:25); second, Lynch, Jackson (1:30); third, Aitken, National (0:20). Time, 8:22 1-10.

Two hundred and fifty miles, for 1909 or 1910 stock chassis, 301 to 450 cubic inches‘ piston displacement, minimum weight 2,100 pounds; for the Prest-O-Lite trophy – Won by Burman, Buick; second, Clemens, Stoddard-Dayton; third, Merz, National. Time, 4:38:58 2/5

One mile, against time, to lower circular track record of 0:51, held by Ralph De Palma-Oldfield, Benz. Time, 0:43: 1-10.

Second Day – Friday.

Five miles, for stock chassis, 231 to 300 cubic inches‘ piston displacement – Won by Strang, Buick; second, Chevrolet, Buick; third, Stutz, Marion. Time, 4:48.

Ten miles, for stock chassis, 301 to 450 cubic inches‘ piston displacement – Won by Merz, National; second, Chevrolet, Buick; third, De Hymel, Stoddard-Dayton. Time, 9:16 3-10.

One mile record trials, against mark of 0:43 1-0 made by Oldfield-Oldfield, Benz, 0:43%; De Palma, Fiat, 0:4835; Zengel, Chadwick, 0:4925.

Ten miles, for cars entered in the 300 miles Wheeler & Schebler Trophy race – Won by Aitken, National; second, Lytle, Apperson; third, Mulford, Lozier. Time, 9:263/5.

Fifty miles, for stock chassis, 161 to 230 cubic inches‘ piston displacement – Won by Wright, Stoddard-Dayton; second, Schwitzer, Stoddard-Dayton. Time, 59:23 1-10.

Ten miles, free-for-all – Won by Zengel, Chadwick; second, Aitken, National; third, Ford, Stearns. Time, 8:23%. World’s record.

Five miles, free-for-all, handicap – Won by Merz, National (0:20); second, Aitken, National (0:10); third, Miller, Stoddard- Dayton (0:30). Time, 4:25.

One hundred miles, for G & J trophy – Won by Strang, Buick; second, De Witt, Buick; third, Stillman, Marmon; fourth, Harroun, Marmon. Time, 1:32:482.

Final Day – Saturday.

Fifteen miles, free-for-all, handicap – Won by Kincaid, National (1:00); second, De Palma, Fiat (scratch); third, Stillman, Marmon (1:15). Time, 14:232.

Ten miles, American amateur championship – Won by Hearne, Fiat; second, Ryall, Buick. Time, 9:44 3-10.

Twenty-five miles, free-for-all – Won by Oldfield, Benz; second. De Palma, Fiat; third, Zengel, Chadwick. Time, 21:21 7-10. World’s record.

Kilometer record trial s -Oldfield, Benz, 0:26%; Christie, Christie, 0:28 7-10; Zengel, Chadwick, 0:29 9-10.

Three hundred miles, for Indianapolis Motor Speedway Trophy – Stopped in 235th mile, owing to accident, and declared no contest. First three men, as follows: Lynch, Jackson; De Palma, Fiat; Stillman, Marmon. Time, 4:13:3125.

Photo captions.

Page 919 – 924.

PANORAMIC VIEW SHOWING FINISH OF FIFTY MILES RACE ON SECOND DAY OF CARNIVAL

SCHWITZER WINNING AND WRIGHT ABOUT TO PASS STARTER WAGNER, BOTH CARS STODDARD-DAYTON

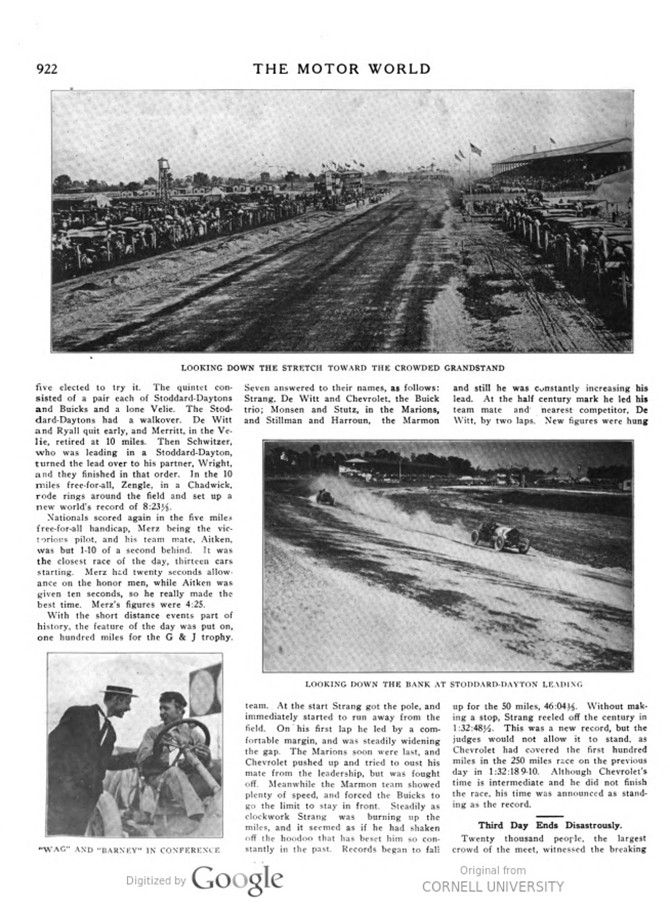

LOOKING DOWN THE STRETCH TOWARD THE CROWDED GRANDSTAND

„WAG“ AND „BARNEY“ IN CONFERENCE – LOOKING DOWN THE BANK AT STODDARD-DAYTON LEADING

AFTER START OF 300 MILES RACE-COUNT THE CARS BURIED IN DUST

LOOKING UP THE BANK AT AITKEN’S SPEEDING NATIONAL

ONE OF THE PRIVATE GRANDSTANDS

LOCAL DEPARTMENT EXTINGUISHING FIRE ON BUICK

WHERE MERZ’S NATIONAL WAS WRECKED ON SATURDAY