Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

The Automobile, Vol. XXX (30), No. 23, June 4, 1914

Thomas, in Delage, Wins

First Four Places in 500-Mile Sweepstakes Taken by Delage and Peugeot – Oldfield in Stutz Fifth

By J. Edward Schipper

INDIANAPOLIS SPEEDWAY, IND., May 30. – Special to THE AUTOMOBILE.

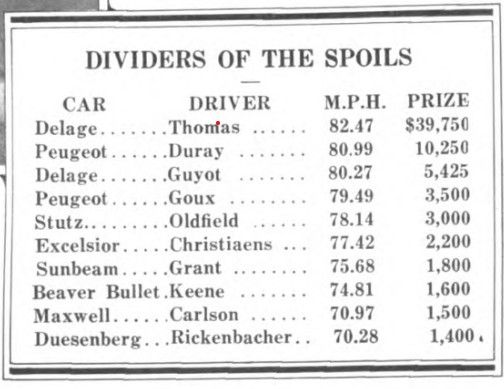

Once more the tricolor of France waves triumphant over the victors of the Indianapolis 500-mile automobile race. Réné Thomas, driving his Delage, a new car to compete in this country, around the 2.5-mile saucer with the regularity of clockwork, finished first in the record time of 6 hours 3 minutes and 45 seconds, or an average speed of 82.47 miles an hour.

Duray Is Second

Seven minutes behind the victor, driving for France, and a matter of $10,000 in prize money, came Arthur Duray in a privately entered Peugeot. Flashing across the tape in the time of 6 hours 10 minutes and 24 seconds, he captured second place at an average of 80.99 miles an hour. Albert Guyot in another Delage crossed the tape 4 minutes later, taking third place. Fourth place was captured by Jules Goux in another Peugeot. Goux was the winner last year.

The first American to finish was Barney Oldfield. The veteran piloted his Stutz at an average of 78.15 miles an hour, and at this speed captured fifth place. The others to finish were the Excelsior, driven by Christiaens, sixth; Sunbeam, Grant, seventh; Beaver Bullet, Keene, eighth; Maxwell, Carlson, ninth; Duesenberg, Rickenbacher, tenth; Mercedes, Mulford, eleventh; Duesenberg, Haupt, twelfth; Keeton, Knipper, thirteenth.

It was by far the fastest of the four 500-mile races so far held on the Speedway. The first four men to cross the finish line, all Frenchmen, too, by the way, exceeded the record time of 78.72 miles an hour made by Dawson in 1912. At the time of the elimination trials the speed shown by the foreign contestants caused it to be freely predicted that 80 miles an hour would be exceeded by the winner. The first three men across the line did better than that speed.

Thomas in the Delage not only won the prize for first place but also picked up the prizes which were provided for the leader at each 100 miles, netting $37,000, including accessory money.

Foreign Drivers Win $61,125

Last year the French team carried away $26,500, Goux having won $20,000 with his Peugeot; Guyot, Sunbeam, $3,500 for fourth place, and Pillette, Mercedes-Knight, $3,000 for fifth. In addition, last year Mulford’s Mercedes was another foreign make to win cash making four in the money as against six this year. All six of the foreigners who finished won prizes. Of the seven Americans to finish only four were in the money. Foreign drivers this year won $61,125.

America built high hopes on Joe Dawson, winner of the 1912 Speedway meet and today at the wheel of a Marmon. Sad fate removed him from the duel just after he had covered 100 miles. At that time Dawson was driving in seventh place, only 39 seconds back of Duray, who was leading, and but 4 seconds behind Thomas the eventual winner. Dawson was following Gilhooley in the Isotta when the latter blew a right rear shoe while near the outside of the track. The Isotta struck the cement wall at the outside and then started across the track to the inside, turning turtle twice and landing on the driver and mechanic in the middle of the brick track on which twenty-six other cars were running at that time. There was a narrow space between the wrecked Isotta and the cement wall at the outer edge of the track. Wilcox, driving the Gray Fox, was close behind the Isotta and drove through this space. Back of him came Dawson, but just as Dawson approached, the Isotta mechanician began to crawl from under the wreck and towards the outside wall. Dawson realized that to follow the Gray Fox would be to strike the wounded mechanic. Instead he veered to the inside of the Isotta, but his Marmon skidded, turned turtle twice and landed on the soft ground inside the track. Dawson was severely injured internally and was removed to the hospital with even chances for recovery. Gilhooley and the two mechanics were badly lacerated but not severely injured.

Many mishaps to the cars occurred during the first 100 miles, when the fight was fiercest. Cooper’s Stutz was in third place when his car went out and within hailing distance of the leader. His relief driver was at the wheel when a tire blew out and he ran off the track, breaking two wheels. This was in the 120th lap. When Boillot went out in the 142nd lap he had just taken the lead, which he had regained but a short time before. The cause of his undoing was a tire which blew out when going into the second turn. The tire hit him in the arm and bruised it and also tore off his necktie. As a result of the wrench the car frame was broken and destroyed his chances of finishing.

The Smallest Car’s Big Showing

Significant as is the victory of the French cars, the most striking feature of the race was the fact that the Duray Peugeot car finished second. This car, although somewhat erroneously called the Baby Peugeot as it had nothing in common with the small car of that name, which was by far the smallest car of the race, with a piston displacement of but 183 cubic inches, ran a race that put to shame the big specially constructed racing machines that were designed to come just under the displacement requirement of 450 cubic inches. It was little less than a complete triumph for the small high-speed motor.

All Credit to Oldfield

Today has been a bad day for America. Our hopes have been crushed to earth one after another, and when 300 miles of the distance were covered those on whom we had staked most were gone; but thanks to the American veteran track driver, the hero-worshipped Barney Oldfield, we got fifth honors, Oldfield’s Stutz being the only American car to land in the first seven places. Oldfield drove consistently from start to finish, averaging 79.14 miles per hour, and was loudly applauded when he drew up at his pit, being the first American driver and the first American car to finish the 1914 American classic.

When the thirty contenders for the Speedway’s $50,000 cash lined up today, we all knew our sons were to meet foreign foemen worthy of their steel piloting cars than which none can be better built.

But we hoped and we trusted. We looked to Mercers, to Stutzs, to the new Maxwells, to Dawson, the 1912 winner in his Marmon, and to others. But the fates were against us. One by one our idols were shattered; one by one our chances faded, and when the end came and the triumph of the tricolor was complete all our hopes clung to the veteran, Oldfield, and we were glad that he was able to beat off the two other drivers and two other foreign cars who finished, Christiaens, who got sixth place in the Belgian Excelsior, and our native son Harry Grant, who carried off seventh honors with an English Sunbeam.

America Gets Last Three Places

To America came the last three places in the money, positions eight, nine and ten. Keene, a newcomer, in a car of his own make, named the Beaver Bullet, was eighth; Carlson, in one of the new Maxwells built by Ray Harroun, was ninth, and Rickenbacher, well-known to American enthusiasts, took tenth place in a Duesenberg car. His average was 70.82 miles per hour.

American hopes voiced by the 110,000 present fell by the wayside when the two Mercers piloted by such Speedway veterans as Wishart and Bragg were eliminated. Both were dangerous contenders until engine troubles developed in the 300-mile zone. Wishart was running fourth at 100 miles but 29 seconds back of the leader. At 200 miles he was in third place and only 38 seconds behind Duray, then leading in the little Peugeot. At 300 miles he was within 3 seconds of Thomas in the Delage, who was then in the lead, having passed Duray. But, when hopes were highest, misfortune came soonest; his camshaft broke and he was out.

Scarcely better fortune awaited his teammate, Caleb Bragg, who, running neck and neck with him for many laps, was in fifth place at 100, sixth at 200 and well up on approaching the 300, when eliminated by a broken magneto drive shaft.

So went three American favorites, and as each was eliminated Europe’s share in the $50,000 increased. America had hoped that the two Maxwell cars which were uncertain factors, due to being completed only a few weeks before the race and not properly worked in, would weather the gale, and after Tetzlaff had qualified next to Boillot and Goux in the preliminaries many looked for him to be a strong defender of American prestige. But, alas, trouble came early. A valve rocker arm broke and Tetzlaff was out before a century had been covered.

A Reconciliation of Rivals

It was an open secret before the race that the rivalry between the Peugeot and Delage teams was intense, but a second chapter is added to this story in telling of the contempt of Goux and Boillot for the Duray Peugeot entry. This was because he was driving, not for the Peugeot factory, but for a private sportsman of France. Besides it was thought that his car was so diminutive that he would have no chance and would bring humiliation on the Peugeot name. At the finish of the race none were quicker to hail Duray than Goux and Boillot as the saver of the Peugeot name and to congratulate him on the glorious showing he had made.

Great disappointment was expressed on all sides when DePalma withdrew because of the excessive vibration of his car, which showed itself in the preliminary trial. This withdrawal on his part made it possible for the Isotta to start and also made it possible for the accident which afterward occurred to happen. Before the DePalma Mercedes was excused Pullen was given a chance to drive the car, but declined, offering the reason that the car was not in proper condition. The car was then officially excused by the referee.

Thirteen Starters Finished

Of the thirty starters, seventeen fell by the wayside and thirteen finished the five centuries on the brick track. An analysis of those unfortunates shows that they were eliminated at two periods during the race, the first period of elimination being between miles 100 and 180 and the second period being between 300 and 380 miles. In the first period seven cars were eliminated and in the second one six were dropped out, leaving but four others that were removed from the race very close to these two periods. This situation shows that by dividing the race into five divisions or centuries of 100 miles each the odd numbers, centuries one, three and five were the fortunate ones, and the even numbers, two and four those in which most cars were eliminated.

When 120 miles of the distance were covered seven cars were out; when 220 miles were covered ten were out; there were thirteen out at 300 and all seventeen at 380 miles.

Motor Parts Were Weak

Further analyzing the tale of elimination in the race it is found that nine of the seventeen, or over 50 per cent., were eliminated due to engine trouble, valves, camshafts, connecting-rods, crankshafts and other parts giving way. Bragg broke a magneto shaft driver; Wishart broke a camshaft; Tetzlaff had a broken valve rocker arm; Anderson broke a crankshaft; Burman broke a valve; the Ray had a broken cam; the King went out with a broken valve, and the Braender Bulldog with a broken connecting-rod. This tale of broken motor parts shows the necessity of increasing the strength of all motor parts when the output of power is increased.

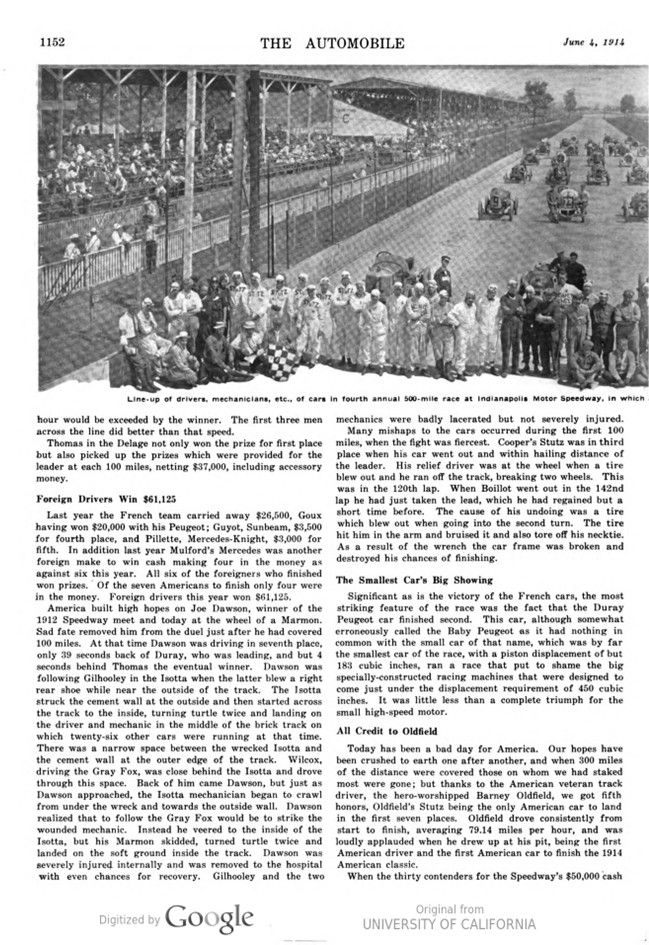

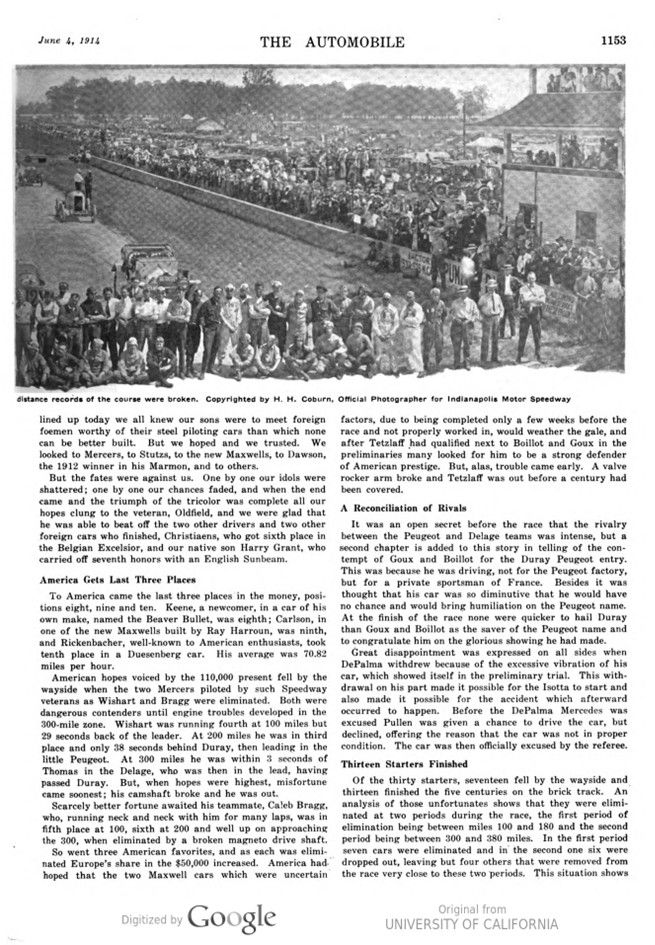

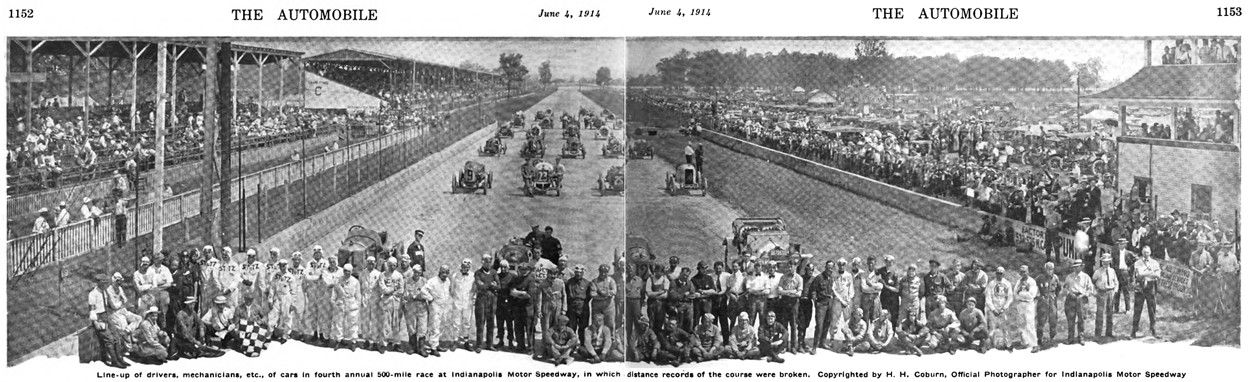

Photo captions.

Page 1151.

The winner and his mechanician – Thomas at the finish

Page 1152, 1153.

Line-up of drivers, mechanicians, etc., of cars in fourth annual 500-mile race at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, in which a distance records of the course were broken. Copyrighted by H. H. Coburn, Official Photographer for Indianapolis Motor Speedway

Page 1154.

Thomas, in the Delage, the winner of the race, passing Christiaens in the Excelsior Duray, in the little Peugeot, leading Grant in the Sunbeam Guyot, in the Delage, which finished third at high speed