The Horseless Age reported on the 1913 Indianapolis 500 mile race with a rather lenghty article. Therefore, it is here shown in two separate parts; „France wins the 500-mile Indianapolis Sweepatakes“ as first part, followed by the second part of their report „The Race from the Pits“. In this 2nd part, the race is explained in view of some of the most significant drivers that determined the course of this 500 mile race.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

THE HORSELESS AGE – Vol. XXXI, No. 23, June 4, 1913, page 1014 – 1019.

The Race from the Pits.

(2nd part of the race report)

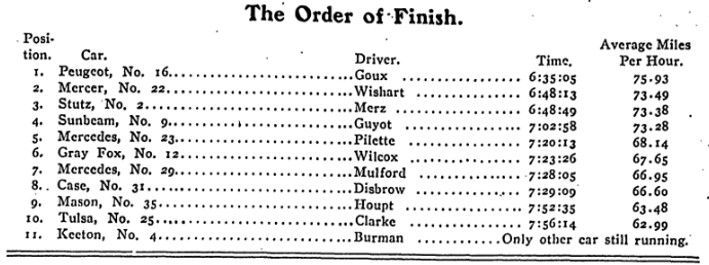

Goux in a Peugeot Scores Victory, With Americans in Second and Third Places —

Wishart’s Mercer Second — Merz’s Stutz Third – Race Not as Fast as Last Year —

80,000 Persons Watch Interesting Contest.

By Chester S. Ricker.

Long before 8 o’clock Friday morning the big racing motors were growling away on the track in preparation for the start and the examination by the technical committee. Every car which started in the race had previously been minutely examined and measured by F. E. Edwards, chairman of the technical committee of the A. A. A. The motors had been measured to determine whether or not they were within the limit of 450 cubic inches, as required under the conditions of the race. Some of them were right up to the edge, the Isottas and the Peugeots measuring about 448 cubic inches displacement. Each of the motors and frames had been marked by the technical committee, and just before the start of the race these marks had to be verified. This necessitated bringing the cars out in good season, so that there would be no difficulty in making a careful examination of each car. By 9 o’clock practically all the cars which were to start in the day’s race were on the course. The exceptions, however, were the two Cases, Nos. 31 and 32, and the Keeton, No. 4, which were held up to the very last minute. The cars were then sent around the course, one at a time, preparatory to the line-up for the start. In front of the big grandstand, they were given the brake and reverse fests. The drivers were instructed to run down the stretch at 40 to 50 miles an hour, and then at a signal from the starter, Charles P. Root, were to apply their brakes in order to determine if they were in proper working order. Every car passed the test without difficulty, although one or two drivers had to make a second trial. Furthermore, every car was made to back up in order to show that they carried reverse gears.

GASOLINE EXAMINED.

As they came down the stretch to the point where they were to line up for the start, the technical committee went among the cars and took samples of gasoline from each one to guard against any possibility of the use of „doped“ gasoline. These samples are filed away in vials, so that they may be analyzed by the technical committee. This examination is mentioned because there seemed to be some belief among those who had watched the Peugeot cars perform that the drivers must have used some kind of dope in their gasoline or some strange kind of fuel in order to obtain the tremendous speeds of which these cars were capable.

THE START.

The cars were lined up four abreast and seven rows deep. As the minute hand reached 10 o’clock „Charley“ Root, the official starter, dropped the flag which started the long race underway. Carl G. Fisher, president of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, set the pace for the first lap in his big white roadster, and at the end of the lap he was going well above 50 miles an hour. The surprise of the second lap, which was the first official circuit, was the appearance of the Peugeot, driven by Goux, in the lead, followed by one of the smallest cars in the race, Evans‘ Mason. On the next lap the little Mason surprised the crowd by leading the Peugeot several lengths as they came down the stretch. The Case, driven by Bill Endicott, dis- appeared from the course about this time. It was reported later that „Bill“ had broken a rear axle drive shaft which completely put him out of the race.

FIRST STOP.

Johnny Jenkins, driving the brilliant red Schacht, next hove in sight with two tires gone, and was the first man to stop at the pits. This occurred at 10:20. He had to replace both tires on the right hand side of the car, which he did in admirable fashion in 1 minute 32 seconds.

MULTI-COLORED CARS.

The field as it swept by, lap after lap, presented a motley array of colors. Almost every combination that could be imagined had been chosen by the drivers. The three Stutz cars were pure white with large, distinctive black figures on the sides of their hoods, on the front of their radiators, and on both the sides and rear of their gasoline tanks. The speedy Keeton, driven by Bob Burman, poked its Renault type hood through the air in a manner which bespoke the wonderful speed which it had. In fact, it was one of the few cars which the public felt was a match for the Peugeots. Besides its Renault type hood, it being the only car in the race so designed, it was also distinctive on account of the brilliant Emerald green body with white figures and white stripes. The Mason cars were undoubtedly the smallest in appearance at the race, as well as the lightest. They were painted a dark brown, and were the only cars carrying this color. The Sunbeam, which ran so unostentatiously throughout the race, resembled a projectile in every way. Its pointed bonnet and long tapering tail gave the idea, and its dark gunboat gray color heightened the illusion. The Henderson was a bright blue and contrasted very sharply in color to the deep blue Peugeots. The Mercedes-Knight and Anel were harlequins in appearance. The Mercedes-Knight was painted orange and white, the body being painted half way up in orange and the rest of the way in white. The Anel was divided just the opposite way, one side of the body being black and the other orange. The Mercedes, driven by Ralph Mulford, was white, but this conflicted with the Stutz in appearance, so Ralph painted the hood and the gasoline tank at the rear a light blue in order to distinguish it. The Isottas were very patriotic in their colors. Their large bodies and running gear were a brillint red, the hoods green and the figures white. The Case team all had light gray, with red trimmings, and the drivers wore gray suits to match the cars, with red racing helmets. The Deltal, Smada, Stearns-Knight and the Shambaugh did not start. race.

STUTZ CARS HAVE TIRE TROUBLE.

Early in the race the Stutz cars gave evidence of the fact that they were hard on tires; in fact, Anderson’s Stutz, which held second place until it went out of commission almost at the end of the race, was the first of the team to make for the pits, at which time a right rear tire was changed. The team made a fairly quick change then, but not one of the record changes which made their pit most interesting later in the Willie Haupt, driving the little Mason, No. 35, which reached tenth place at the finish, was the third man to stop at the pits. He made a fairly rapid change of his right rear tire, taking one minute and six seconds to do it. Merz’s Stutz came in immediately afterward to take a right rear tire, losing a minute and a half in doing it, as the car fell off the jack and had to be jacked up again. This upset the position of the leaders considerably. Goux was the next to stop at the pit and he also took a right rear. Up to this time every man who had come into the pits had had to replace a right rear tire, it being too early for mechanical trouble to have started. This was within the first twenty minutes of running.

DE PALMA CHANGES TIRES.

De Palma, who was running well up in his Mercer, pulled up to the pits with both right tires, front and rear, gone. He leaped out of the machine, grabbed a little three-cornered dagger which he carried for the purpose, and stabbed the right front tire, which had lost its tread, but had not become deflated as yet. This was necessary in order to remove the Michelin rim, with which the car was equipped. It is impossible to remove a Michelin racing rim with the tire inflated. Three minutes were consumed in making the change. The rear tire in this case as had been run for a con- siderable distance deflated and the fabric was almost aflame, so hot was the tire; in fact, the men who helped change it had to use bars to pry the rim off because they could not place their hands upon it. This contributed a great deal to the loss of time. Later in the race the Mercer team became a sharp contender with the Stutz for excellent pit work.

At 10:27 the Mason, driven by Jack Tower, pulled up for a right rear and a left front tire. The engine was missing and examination proved that two spark plugs in No. 2 and No. 3 cylinders were gone. They were replaced, three minutes being consumed in doing the work. The Nyberg, driven by Harry Endicott, appeared at the pits and he lost five minutes repairing his brake equalizer, the brake operating mechanism, and tightening up his shock absorbers. He then continued to appear intermittently at the pits, working at his brakes, until he finally seemed to overcome the trouble which he had experienced with their non-operation. He then had some difficulty with his transmission which eventually put him out of the running.

ANEL SHOD IN 52 SECONDS.

One of the most rapid tire changes in the early part of the race was made by the Anel crew, with Liesaw driving, when a wheel was shod in 52 seconds. The crew were using Michelin rims. The Henderson, driven by Billy Knipper, made its appearance at the pits at 10:40. The engine was missing badly, which was apparently corrected by carburetor adjustment, and „Billy“ got away again after losing three minutes. At 10:40 De Palma’s Mercer rolled into the pits with the main bearings burned out, this eliminating him from the race for good. At almost the same time Caleb Bragg at the wheel of the No. 19 Mercer pulled up at the pits with his magneto shaft broken. Caleb and Ralph were driving identical cars, both big Mercers. As Ralph’s car was out of business the boys at the pit hurried over to it, took out the magneto shaft and put it on Bragg’s car. The change was made in about forty minutes, which is very creditable, and No. 19 was again under way, De Palma having relieved Bragg at the wheel.

GOUX MAKES STOPS.

The Peugeot then came in for the second tire, a right rear one, at 10:48, and made the change in one minute and fifteen seconds. At 10:52 „Ed“ Madden relieved Harry Endicott on the Nyberg, and shortly afterward was out of running on account of his transmission gear shaft sticking. It seemed almost as though Goux had scarcely left the pits before he was back again, this time requiring a left rear tire. While the tire was being changed he took on about five gallons of castor oil, the Peugeots using castor oil throughout the race for lubrication.

Shortly afterward Tower’s Mason took on another spark plug. At 10:57 Zucarrelli, driving the second Peugeot, pulled up at his pit, threw the hood back, looked at his motor, shook his head and climbed into the pit. Listening to the motor as it was, driven away to the garages proved only too plainly that the main bearings of the engine had been burned out.

SLIPPING CLUTCHES THE MASON’S TROUBLE.

The Mason team seemed to be unfortunate in the selection of their clutches or in the protection of them, at least. The motors were extremely powerful but the clutches were inadequately protected against lubricating oil, and before the first hour of the race was over every one of them was slipping. It was a case of unpreparedness more than anything else.

HAUPT’S REMEDY.

Willie Haupt, driver of No. 35 Mason, deserves a great deal of credit for the way he got around his clutch trouble. Haupt got a number of thin pieces of steel about 2 inches long and 12 inch wide. He beat the ends of these down in order to give them a wedge shape so he could drive them underneath the clutch leather. This lifted the leather and allowed him to get his clutch a great deal tighter. After driving in about five of these he did prevent his clutch slipping, but he also prevented himself from disengaging it. He was equal to the occasion, however, and from that time on whenever the car came to the pits he stopped his motor, threw out the gears and coasted in. After the tire change was made he jacked up the rear wheels, threw his gears in mesh and started up the motor. The rear wheel would spin around, but due to the action of the differential the car would not be driven. His mechanician then got out and pushed the car off the jack and as the rear wheel was rapidly spinning the car would get off every time very nicely. This operation would be repeated each time whenever he had to start after making a tire change, the clutch not slipping, but being ineffectual as a disengaging member.

PITS BUSY PLACES.

About a quarter past II the Henderson arrived at the pits with both rear tires off and the engine missing badly. The tires were replaced and the carburetor adjusted, which seemed to correct matters somewhat. Four minutes were consumed in doing this. At 11:30 the Isotta with Trucco up pulled up at the pits and took on gasoline, oil and water. At the same time the driver was relieved by Dave Lewis, his mechanician, and Gilhooly took Lewis‘ place as mechanician on the car. The Gray Fox made its first stop at 11:30, when a right rear tire was changed very quickly. About 11:40 No. 19 Mercer, which was running very well, pulled up at the pits for water. Examination of the motor proved that the heating was due to the water pump being inoperative. A coupling on the water pump shaft had worked loose after shearing the pin which fastened it onto the shaft. This was fixed up in about ten minutes. An hour and fifty minutes after the start of the race Burman in the Keeton drew up at the pits for the first time. He was running beautifully. An examination of each of the tires showed that they did not need replacement. He took oil and gasoline only. The tires were Silvertown cord and these when new have three projections which encircle the tread of the tire. These are about 1/8 inch high. All four of his tires still retained the markings of this 1/8-inch projection although they were worn down considerably. A bushing had worked out of the right front steering knuckle and Burman lost several minutes obtaining another and putting it in place.

MERCEDES-KNIGHT MAKES FIRST STOP.

The Mercedes-Knight, No. 23, the smallest motored car in the race, pulled up at the pits at 11:56. The tires looked as though they were in perfect condition, but no chances were taken by the team manager and he changed three tires. At the same time Pillette took on gasoline and oil.

BURMAN ON FIRE.

About noon Burman disappeared from the bunch which was encircling the track. Report came across the field that he had caught fire the backstretch. This, however, was extinguished by throwing sand over the motor, and a little later he drove up to his pit. The Keeton motor was covered with an inch or more of sand, and was in a condition which made one think it would never run again. Burman, however, was undaunted, and proceeded to clean it up. He had to take off his inlet manifold, and he also changed carburetors, replacing the one which he had with a Rayfield. At the same time Burman was so overcome from having to fight the fire that he was relieved by Hughie Hughes, who so successfully drove the Mercer in the race last year. At the same time the invincible Frenchman, Goux, pulled up at the pits and took his fourth tire, which was a right rear one.

Evans‘ Mason came down the stretch with the left tire wrapped around the brake drum. The entire shoe had come off of the rim and locked itself on the inside of the wheel and around the axle. The most ludicrous thing, however, was the piece of casing which was trailing behind the car. A piece of tire a foot and a half long was trailing 15 feet behind the car on the end of a single string of fabric. About 12:15 the non-appearance of the Mason No. 6 caused some comment, and the report soon came that Jack Tower had turned over and had broken his leg; also that his mechanician had several ribs broken.

SHORT HALTS AT THE PITS.

At 12:22 Charley Merz, driving Stutz No. 2, pulled up at the pit for a right rear tire. He took on gasoline and oil at the same time in order to economize time. At 12:35 Louis Disbrow, driving the successful Case entrant, No. 31, stopped to take on gasoline, oil and water and changed a right rear tire. At the same time Kilpatrick relieved Disbrow as driver. At 12:45 the Gray Fox No. 12 pulled up at the pits to take on oil and gasoline. This was taken on in the remarkably short time of one minute and twenty-five seconds. This, however, was immediately beaten by the Isotta crew when Harry Grant pulled up at the pits for oil and gasoline and took on a goodly supply of both in fifty-five seconds.

At 12:53 the Sunbeam stopped for the first time. The car had then been running nearly three hours and was making admirable time. The pit work, however, was very slow, and as a result the crew lost four minutes in changing a left front tire and taking on oil and gasoline. Immediately afterward the Case, driven by Kilpatrick, tried to pull in at the pit and failed to stop, running into the southeast turn. Finding he could not stop he opened up the motor and finished the lap. He took due precaution the next time and started to slow down well before he reached the pits. The difficulty appeared to be in his emergency brake lever, the pin which held this in place having sheared off. He lost twenty minutes making this repair, having to get the broken parts of the pin out and replace it. At the last moment he found no taper pins available for that particular repair and so took a punch, driving it into the taper hole and then breaking it off. Apparently it stayed in for the rest of the race, for he experienced little or no difficulty in stopping thereafter.

At 12:08 Goux took on water and changed a right front tire in one minute and twenty-two seconds. This was the fifth change he had made.

QUICK VALVE CHANGING.

The over-head valves on the Gray Fox gave evidence of trouble at 1:25. Wilcox lost seven minutes changing the exhaust valves in No. 2 and No. 3 cylinders, but got away very quickly considering the work that had to be done. At 1:40 Bob Burman, who was again driving the Keeton, pulled up at the pit with a good-sized hole in the bottom of the gasoline tank. He lost eighteen minutes and fifteen seconds trying to repair this. Hughes solved the problem by getting all of the spectators within hearing to chew gum for him and then collected the gum and put it into the hole. This apparently stopped the leak, temporarily, for Hughie made fifty miles before he had to stop again on the same account. At 1:42 Ralph Mulford made his first stop during the race when he took on fuel.

At about the same moment the Sunbeam pulled up at the pit and both rear tires were changed. Guyot took this opportunity to take on oil and gasoline, some eight minutes being consumed in doing this. This was in great contrast with the pit work on No. 19, Mercer, where oil, water and gasoline were put into the Mercer, which De Palma was driving at that time, in less than two minutes. Almost as good work, however, was done at the Peugeot pit, where oil and gasoline were taken on in two minutes and a half. The three cars, Mercedes, Sunbeam and Peugeot, were all in the pits taking on their supply of fuel at about the same moment. This made the work extremely interesting, as there was sharp competition between the crews.

PEUGEOT CHANGES SIXTH TIRE.

At 2:10 Goux again drove up at the pits as his car required another right front tire. The change was made in remarkably good time, 55 2/5 seconds being consumed.

Tetzlaff’s Isotta was pushed up to the pits at about this time, by the relief driver and mechanic, Dave Lewis and Gilhooly. At the meeting of the drivers the night before the race a new ruling had been made in regard to pushing a car. As a driving chain had broken the crew thought it would save time to push the car down to the pits and put on a new chain there, rather than go all the way across the track to get a new chain and bring it back, but to their sorrow they found themselves disqualified when they had a car which was running in beautiful shape.

HUGHES FIXES GASOLINE ΤΑΝΚ.

Hughes ran out of gasoline on the back stretch, due to the leak in the Keeton gasoline tank. He was wise enough not to push his car as he did last year, but took advantage of the momentum it had and coasted around to the pits. In fact, the car rolled into the pits going scarcely two miles an hour, but by so doing he was fortunate in not being disqualified. Hughes immediately got busy and began to repair the hole where the gum had fallen out. This time he made an emergency plug of a couple of rubber washers, one on the outside and one on the inside of the tank, using a machine bolt and a couple of steel washers to clamp the two pieces together. It took him thirty minutes to effect the repair, but when he was through the tank no longer leaked.

Ralph Mulford driving the Mercedes was equally unfortunate in running out of gasoline. He had to get a five-gallon can of gasoline and carry it all the way across the course instead of rolling up to his pit and taking it on there. This very nearly lost Ralph a place in the money.

ANDERSON’S ADMIRABLE PIT WORK.

The Stutz and Mercer teams gave the finest examples of rapid tire changes to be seen at any race. The No. 3 Stutz was running in second place and every second counted, when about 3 o’clock he had to come in for a tire. The casing was a right rear one, and was thrown as he came down the stretch. It rolled almost the entire length of the grandstand, hoop fashion. Gil Anderson, however, pulled up to his pit and took just thirty seconds to get a new tire. Three or four times afterward he made equally as quick changes, one of them being clocked with a stopwatch in 25 4/5 seconds from the time the wheels stopped rolling until they began to roll again.

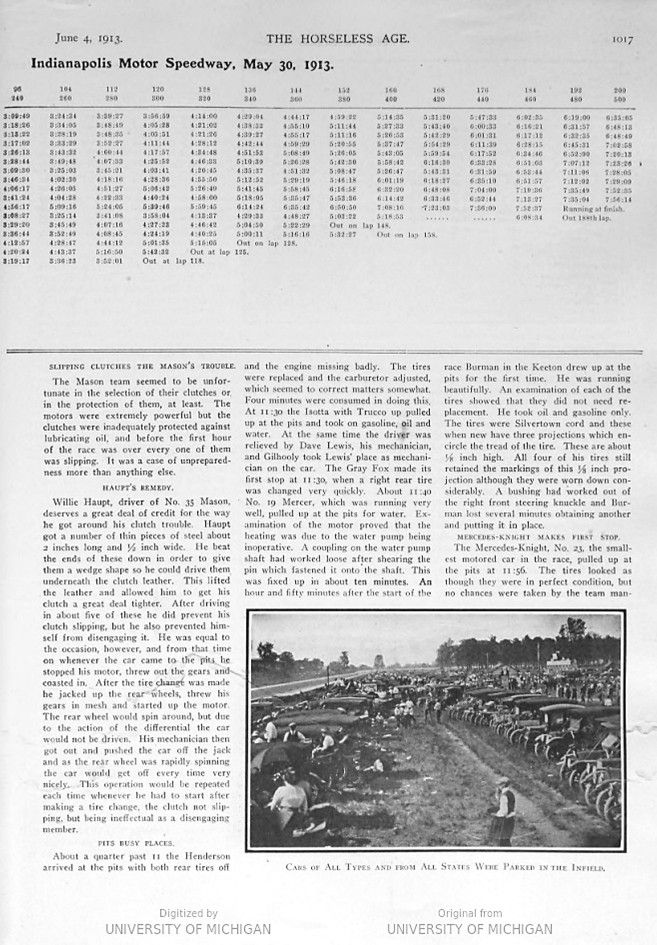

A QUICK REPLENISHMENT BY GOUX.

At 3:22 Goux, driving No. 16 Peugeot, stopped for oil, which he took on in 48 2-5 seconds. This was fast, considering that the oil tank is immediately underneath the mechanician’s seat and is not very accessible. The mechanician never got out of the car, merely pulling himself onto the back of the seat and assisting the men in putting the oil into the tank immediately below. While he was doing this Goux imbibed in a mug of champagne. He got away in a hurry, but tried to make the lap so fast that he lost a rear tire and was back again at the pits. The tire change was made in about two minutes. When Goux pulled in at the pit at 3:48 for another tire the hopes of the Stutz enthusiasts were greatly elevated, for he was beginning to have a surprising amount of tire trouble, while the Stutz was having less and was running very close in second place. Goux ran for about one-half an hour and came in for another left rear tire at 4:14. Anderson’s Stutz pulled up about six minutes later for a right rear tire and five minutes later for another rear tire. This time, however, the motor failed to start, and an examination proved that one of the timing gears had been stripped. This dropped Gil Anderson out of the race after he had run in second place for so many miles and twice had been leader by a few seconds.

STUTZ ON FIRE.

The Peugeot, driven by Goux, and the Mercer, driven by Spencer Wishart, both crossed the line in the order named. Stutz No. 2 was about five minutes behind the Mercer and going well. As it was coming down the stretch to receive the green flag from Starter Root, those along the pits could see the flames licking up the radiator and the frame of the car. Little Merz, however, was game and decided to complete his last lap, despite the fire, if it could be done. He and his mechanician were protecting themselves as best they could from the flames which were creeping back through the floor boards. The severity of the fire can be well imagined when one considers the 90-mile breeze which was blowing back through the radiator and driving the flames upon the occupants of the car. He finished, however, in admirable form. All the water connections had been burned away, the radiator was almost melted and the motor was red hot, there not being a drop of water in the radiator or the cylinders. The nerve and pluck of the Indianapolis boys who stuck to this car and put it across the finishing line under these circumstances is exceedingly creditable.

The Mercedes-Knight had run very consistently up to 5:06, when it was seen to come down the course with the motor dead. The driver vainly attempted to stop in time to pull up at his pit. He locked his wheels, and slid the length of the grandstand and into the southeast turn. Here examination soon proved that the motor was not getting any gasoline, and the carburetor was pulled apart, cleaned and put back together again and the motor started. It finished in fifth place. The Sunbeam, which had finished before him, ran so noiselessly and in such a touring-car way that one hardly noticed that it had gone into the pits and finished the race. Both it and the Peugeot were remarkably cool after the long grind which they had had.

REMARKABLE TIRE ECONOMY.

One of the most striking evidences of tire economy which was seen during the day appeared on the Mercedes, driven by Ralph Mulford. This was equipped with Braender tires, made by the Rutherford Tire Co. in New Jersey. Ralph Mulford. had 36×5 in the rear and 36×4 in front. He made the entire distance on the same casings with which he started the race.

Photo captions.

Page 1015. PREPARING THE „LINE-UP“ FOR THE START. – MERZ IN THE WHITE CAPPED STUTZ DROVE A CONSISTENT RACE AND TOOK DOWN THIRD MONEY.

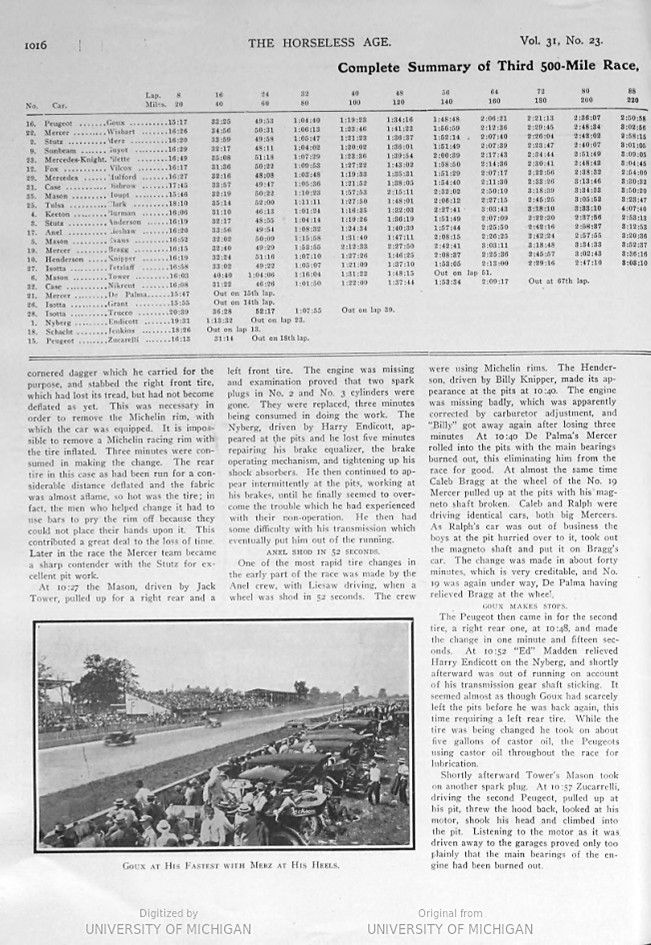

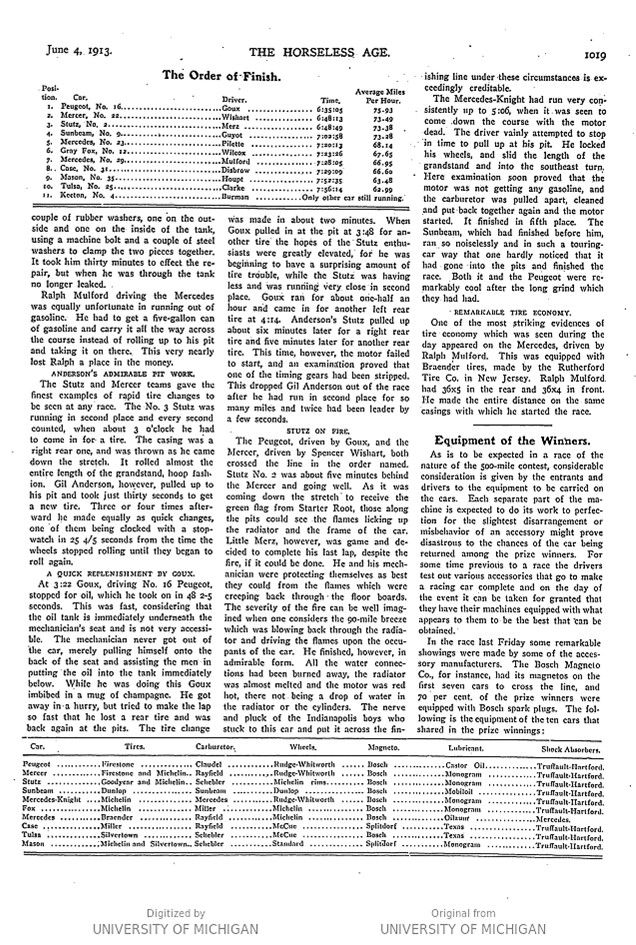

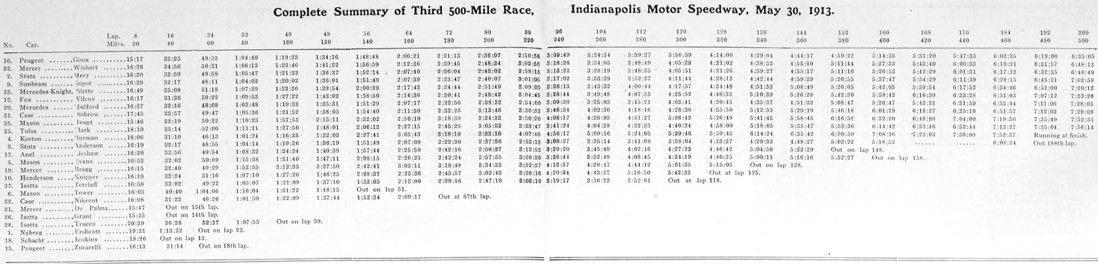

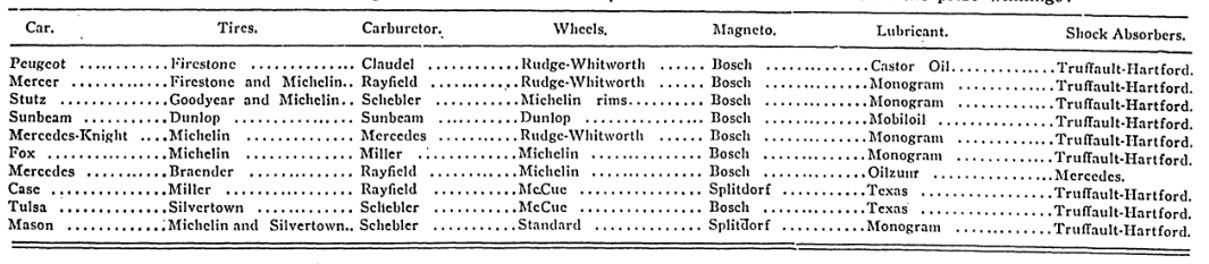

Page 1016 – 1017 Complete Summary of Third 500-Mile Race, Indianapolis Motor Speedway, May 30, 1913.

GOUX AT HIS FASTEST WITH MERZ AT HIS HEELS. – CARS OF ALL TYPES AND FROM ALL STATES WERE PARKED IN THE INFIELD.

Page 1018. THE PRESS STAND WITH THE PREVIOUS 500 MILE WINNING CARS-MARMON NO. 32, NATIONAL No. 8