The 1902 Paris-Vienna Race was extremely extensive reported in ths article of the US magazine „Motor Age“. Yet being in their second volume year, this report of that early motor racing event „over the pond“ seems to have been closely linked to the British magazine „The Autocar“. But it shows, how meticulous and secure this magazine followed European motor racing, as well as technical developments in these early days of motor racing.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

MOTOR AGE Vol. II, No. 3 – Chicago, July 17, 1902

THE RACE FROM PARIS TO VIENNA

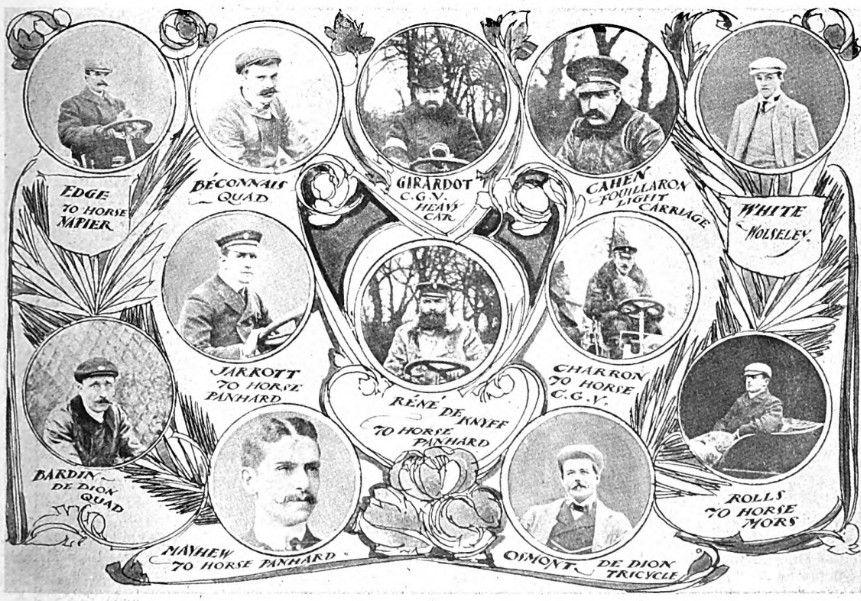

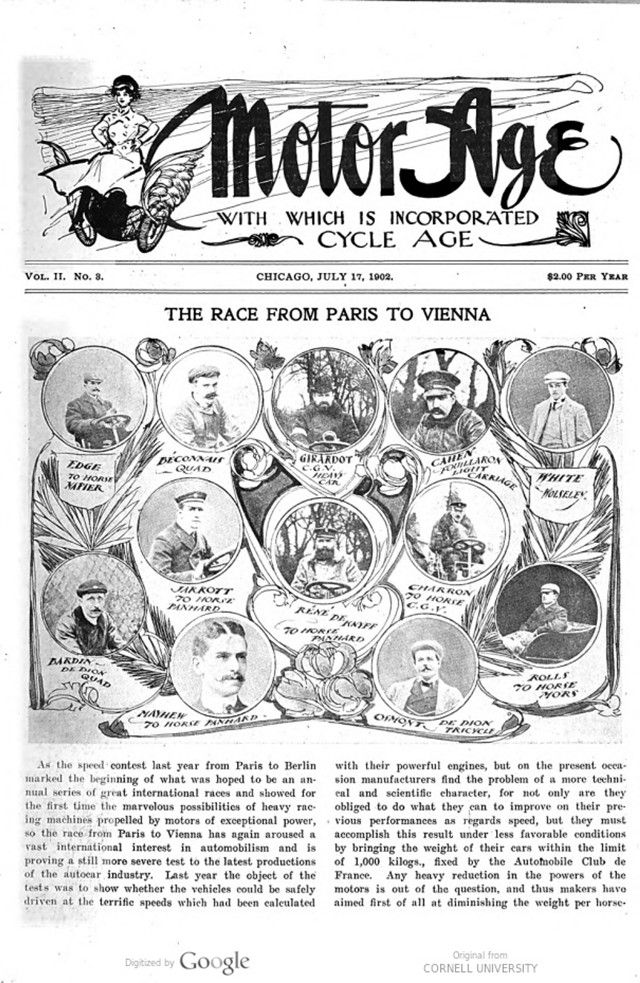

EDGE TO HORSE NAPIER – BÉCONNAIS QUAD – GIRARDOT C.GV. HEAVY CAR – CAHEN FOUILLARON LIGHT CARRIAGE – WHITE WOLSELEY – JARROTT 70 HORSE PANHARD – RENE DE KNYFF TO HORSE PANHARD – CHARRON 70 HORSE C.G.V. – BARDIN DE DION QUAD – MAYHEW 70 HORSE PANHARD – OSMONT DE DION TRICYCLE – ROLLS TO HORSE MORS

As the speed contest last year from Paris to Berlin marked the beginning of what was hoped to be an annual series of great international races and showed for the first time the marvelous possibilities of heavy racing machines propelled by motors of exceptional power, so the race from Paris to Vienna has again aroused a vast international interest in automobilism and is proving a still more severe test to the latest productions of the autocar industry. Last year the object of the tests was to show whether the vehicles could be safely driven at the terrific speeds which had been calculated with their powerful engines, but on the present occasion, manufacturers find the problem of a more technical and scientific character, for not only are they obliged to do what they can to improve on their previous performances as regards speed, but they must accomplish this result under less favorable conditions by bringing the weight of their cars within the limit of 1,000 kilogs., fixed by the Automobile Club de France. Any heavy reduction in the powers of the motors is out of the question, and thus makers have aimed first of all at diminishing the weight per horsepower, with the result that the majority of manufacturers are fitting more powerful engines than last year without increasing the weight. In fact, in many cases the engines, while being more powerful than last year, are appreciably lighter.

It is, however, in the frames and propelling machinery that makers have been cutting away material, and a cursory examination of the vehicles would seem to show that they have narrowly skirted the bounds of imprudence; but when it is seen how much care has been taken in the construction of each piece, and how nothing has been left to hazard in the selecting and working of the best possible material, there seems to be every reason for believing that manufacturers have got the maximum of power and strength for the weight allotted to them. We have shown how this has been done in the Charron, Girardot et Voigt cars, and how in the Panhards the power of the motor has been greatly increased without appreciably adding to the weight, while it is actually lighter than the Paris-Berlin engines. In several types of new racing vehicles the secondary or „false“ chassis has been suppressed, and the motor and gear box are bolted directly on to the main frame. In the Mors cars there is some mystery about the powers of the new motors, which are rated at 45 horsepower, though, of course, developing much more, and the firm is said to have made no attempt to construct more powerful engines, since it has preferred to secure a better utilization of propelling effort.

In the Gordon Bennett cup car, driven by Fournier, however, the engine is much more powerful, and we should think that it is one of the biggest engines yet fitted to a French autocar. The four cylinders are enormous and look more like developing between 70 and 80 horsepower than the 45 or 50 horsepower at which it is rated. For such an engine the underframe appears extremely light. The change speed gear is entirely different from that on the old Mors cars. For the first three speeds the primary shaft carries the usual train of sliding wheels, and both the primary and secondary shaft gear on bevel wheels on each side of the differential. At the low speeds the end bevel on the primary shaft runs free, and when the sliding train is pushed right forward a clutch keys this loose pinion and the drive is direct. A feature of these cars is the system of pneumatic suspension, consisting of a series of cylinders and pistons interposing between the axles and the frame. The cylinder is fixed to the frame above the spring and the piston rod at the junction of the spring with the axle, and as the pistons are airtight, they serve the purpose of pneumatic buffers to prevent the wheels from jumping on the road, at the same time they save the springs and considerably reduce any liability to breakage.

The race to Vienna is not only a test for speed, but more especially for endurance, as it appears that the road over a third of the distance is far from being as good as the course to Berlin last year. From Paris to Belfort, a distance of 253 miles, the cars will be able to travel at full speed, and it is quite possible that we may look for some phenomenal performances on this section. Between Belfort and Bregenz the distance is 194 miles, and the competitors will have to travel through Switzerland as tourists. The decision not to race over this section seems to have disappointed the Swiss, who had been looking forward to an opportunity of seeing the cars travel at high speeds; but the authorities express themselves satisfied with the determination of the automobile club to neutralize this part of the course, for though they would not have run the risk of being accused of hostility to the automobile by prohibiting the race, they nevertheless recognize that some of the roads are not suitable for racing speeds. Between Bregenz and Salzburg – 209½ miles – the troubles begin. Until a few days ago there was a question of neutralizing a part of the course, and especially the passage of the Arlberg, which was blocked with snow; but it is now stated that the pass has been cleared, and though extreme care will be needed in driving the cars, there is now no longer any question of neutralizing this section. Those competitors who have been over the course are far from being enamored of the road to Salzburg, which is not only narrow and often in bad condition, but the gradients here and there are very dangerous, some of them being said to be as much as one in five, while the drains and ridges crossing the road are innumerable and will keep competitors perpetually on the lookout. To make matters worse, the heavy rains made the going terrible for those who have been prospecting the route, but it is to be hoped that this difficulty at least will be overcome with the change in the weather, though it is clear that we cannot look for fast speeds on the way to Salzburg, and if the vehicles come through unscathed it will be a question of good luck and careful driving. From Salzburg to Vienna the going is satisfactory, and competitors will be able to once again fully test the speed capabilities of their vehicles upon this section of the route.

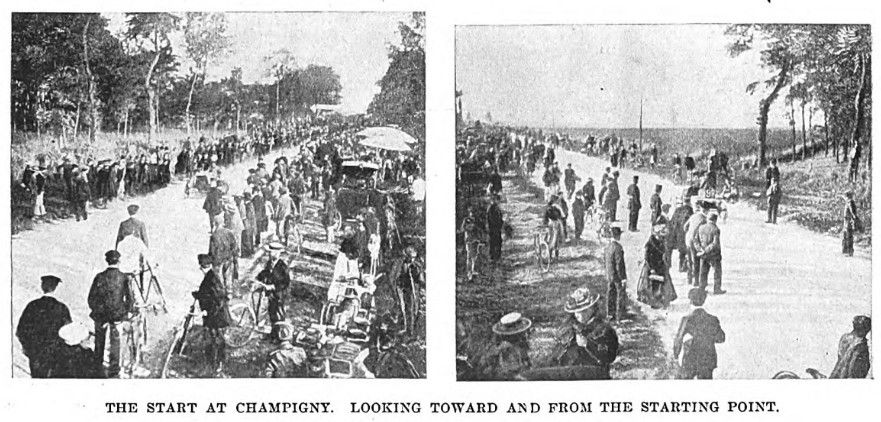

A special train which had been organized to follow the race carried more than its usual complement of passengers. The morning opened remarkably fine and gave every promise of a hot and clear day. It was broad daylight when we left Champigny by the long hill leading to the plateau which had been the scene of several similar gatherings, and it was from here that the start took place for the races to Amsterdam and Berlin. The start was first of all given to the vehicles for the Gordon Bennett cup, which was to be competed for in two stages, from Paris to Belfort and from Bregenz to Innsbruck, making a total distance of 379 miles. Of the three Wolseley cars only one, driven by Mr. Austin, took part in the race, and S. F. Edge therefore competed with his new Napier vehicle. Promptly at 3:30 M. Girardot was sent off with his C., G. V. car, and then followed, at intervals of two minutes, Fournier in a Mors, S. F. Edge and the Chevalier Rene de Knyff. Considerable interest centered in the Mors, which started in a remarkably fine style and got up full speed in a way that did not leave the slightest doubt as to the power of the vehicle. The others were sent off, and the chief machines were as follows:

Cars weighing from 650 to 1,000 kilogs. (12 cwt. 3 qrs. 5 lbs. to 19 cwt. 2 qrs. 20 lbs.) – Seven 70-horsepower Panhards, one 60-horsepower Panhard, five 40- horsepower Panhards, five 60-horsepower Mors, two 40-horsepower Mors, two 50-horsepower Peugeots, five 12- horsepower Gardner-Serpollets, three 40-horsepower Mercedes, one 24-horsepower De Dion, one 40-horsepow- er Napier and one 30-horsepower Wolseley.

Cars weighing from 400 to 650 kilogs. Two 20-horsepower Mors, six 24-horsepower Darracqs, three 18-horsepower Decauvilles, three 18-horsepower Gobron-Brillies, one 24-horsepower Panhard-Levassor, four 20-horsepower Clements, one 16-horsepower. Peugeot and one 16-horsepower Renault.

Cars weighing 450 to 650 kilogs. – Four 18-horsepower Gobron-Brillies, five 18-horsepower Decauvilles, two 16- horsepower Renaults (the one driven by M. Marcel Renault did fastest time for the entire course), four 24-horsepower Panhard-Levassors, three 16-horsepower Delahayes, three 16-horsepower Darracqs, four 24-horse- power Clements and three 20-horsepower Dechamps.

Cars up to 400 kilogs. – Two 10-horsepower Georges Richards, four 8-horsepower Renaults, two 12-horsepower Darracqs and three 8-horsepower Corres. Motor tricycles-Three 7-horsepower De Dions. Motor quadricycles – Two 7-horsepower De Dions. Motor bicycles – Three 3-horsepower Clements, two 2-horsepower Werners and three 3-horsepower Laurin- Klements.

Another short stop was made at Chaumont, where we learned from the control that Fournier had just passed through. Neither De Knyff nor Edge had yet passed, and it had long been understood that Girardot had broken down. Soon after leaving Chaumont the road again ran parallel with the railway, and the dust, which was still hanging in the air, showed that Fournier could not be far ahead. The dust thickened and just as we were anticipating a fine struggle between the Mors and the express, which was now traveling at its maximum rate, Fournier drew up to the side of the road and stopped. He threw up his arms as a signal that something was seriously wrong. It turned out afterward that a shaft had broken and it was said to be the starting shaft, though it is difficult to understand how this could have stopped Fournier so long as his engine was running. When Maurice Farman slowed down to inquire as he passed, later on, Fournier declared that the damage was „irreparable,“ so it was probably one of the gear shafts.

After seeing the first vehicle started the passengers by the special had to return to Nogent le Perreux, and then another interesting element developed itself in a race between the express and the cars. Just as we were leaving Nangis a car flew past along the road running parallel with the railway. It was going at a terrific speed, appreciably faster than the special, which was doing 50 to 55 miles an hour. For some time, the car gradually forged ahead, and then the road curved outward, when the car got smaller in the distance, like a speck with a white tail, and then disappeared altogether. This was probably Fournier. At Nogent-sur-Seine the train again skirted the road for a considerable distance, but there was no sign of the cars, from which it was clear that they were going as fast as the special express. At Troyes there was a short halt, when it was announced that Fournier had passed through first, with De Knyff second and Edge third.

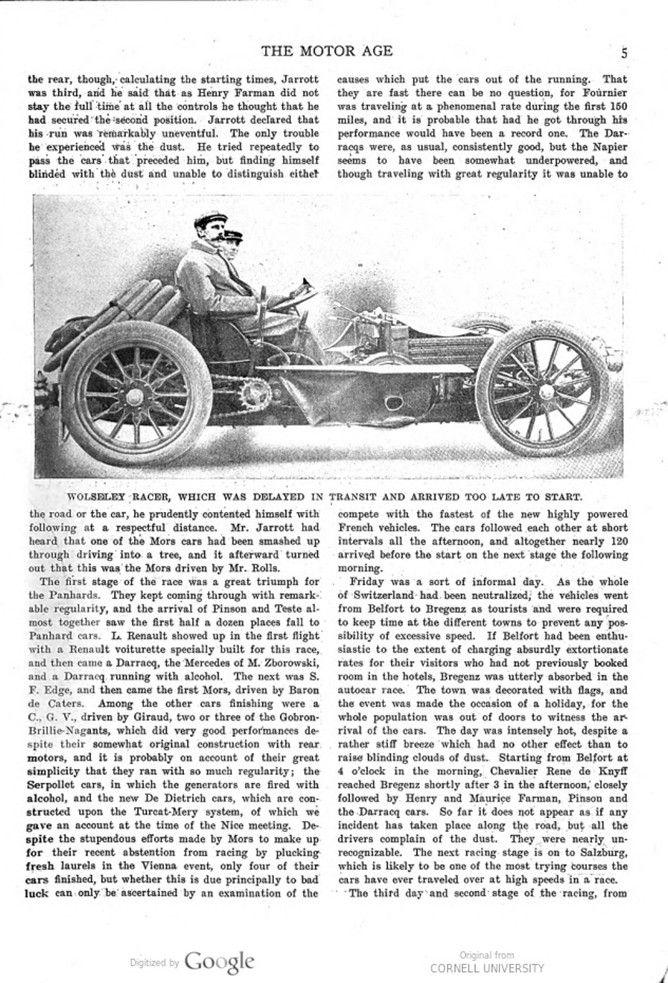

The first stage of the race was a great triumph for the Panhards. They kept coming through with remarkable regularity, and the arrival of Pinson and Teste almost together saw the first half a dozen places fall to Panhard cars. L. Renault showed up in the first flight with a Renault voiturette specially built for this race, and then came a Darracq, the Mercedes of M. Zborowski, and a Darracq running with alcohol. The next was S. F. Edge, and then came the first Mors, driven by Baron de Caters. Among the other cars finishing were a C., G. V., driven by Giraud, two or three of the Gobron-Brillie-Nagants, which did very good performances de- spite their somewhat original construction with rear motors, and it is probably on account of their great simplicity that they ran with so much regularity; the Serpollet cars, in which the generators are fired with alcohol, and the new De Dietrich cars, which are constructed upon the Turcat-Mery system, of which we gave an account at the time of the Nice meeting. Despite the stupendous efforts made by Mors to make up for their recent abstention from racing by plucking fresh laurels in the Vienna event, only four of their cars finished, but whether this is due principally to bad luck can only be ascertained by an examination of the causes which put the cars out of the running. That they are fast there can be no question, for Fournier was traveling at a phenomenal rate during the first 150 miles, and it is probable that had he got through his performance would have been a record one. The Darracqs were, as usual, consistently good, but the Napier seems to have been somewhat underpowered, and though traveling with great regularity it was unable to compete with the fastest of the new highly powered French vehicles. The cars followed each other at short intervals all the afternoon, and altogether nearly 120 arrived before the start on the next stage the following morning.

The arrival took place on the outskirts of Belfort on the top of a slight upgrade, giving a view of a half mile stretch thickly shaded by trees. At about 10:40 a succession of bugle sounds was heard, very faint, in the distance, and then growing louder, and a few minutes afterward a car dropped down the hill in the distance with a cloud of dust and then dashed up the gradient to the control. It was De Knyff with his 50 nominal horsepower Panhard, whose time for the distance of 253.3 miles, including neutralizations, was 7h. 11m. 30s. As M. de Knyff was running with alcohol, for which he had carried out slight modifications to his carbureter and engine, he won the alcohol cup offered by Prince d’Arenberg for the first car arriving at Belfort with this spirit. De Knyff declared that he had not met with the slightest trouble on the road and had not even been obliged to stop for punctured tires. Several other competitors spoke highly of the way in which the tires (Continentals and Michelins) had come out of the ordeal, for they had rarely been put to a more trying test. On finishing they were quite hot. About 20 minutes after the arrival of De Knyff the bugles announced the second car and Henry Farman stopped at the control, followed 9 minutes afterward by his brother Maurice, with C. Jarrott close in the rear, though, calculating the starting times, Jarrott was third, and he said that as Henry Farman did not stay the full time at all the controls he thought that he had secured the second position. Jarrott declared that his run was remarkably uneventful. The only trouble he experienced was the dust. He tried repeatedly to pass the cars that preceded him, but finding himself blinded with the dust and unable to distinguish either the road or the car, he prudently contented himself with following at a respectful distance. Mr. Jarrott had heard that one of the Mors cars had been smashed up through driving into a tree, and it afterward turned out that this was the Mors driven by Mr. Rolls.

Friday was a sort of informal day. As the whole of Switzerland had been neutralized, the vehicles went from Belfort to Bregenz as tourists and were required to keep time at the different towns to prevent any possibility of excessive speed. If Belfort had been enthusiastic to the extent of charging absurdly extortionate rates for their visitors who had not previously booked room in the hotels, Bregenz was utterly absorbed in the autocar race. The town was decorated with flags, and the event was made the occasion of a holiday, for the whole population was out of doors to witness the arrival of the cars. The day was intensely hot, despite a rather stiff breeze which had no other effect than to raise blinding clouds of dust. Starting from Belfort at 4 o’clock in the morning, Chevalier Rene de Knyff reached Bregenz shortly after 3 in the afternoon, closely followed by Henry and Maurice Farman, Pinson and the Darracq cars. So far it does not appear as if any incident has taken place along the road, but all the drivers complain of the dust. They were nearly unrecognizable. The next racing stage is on to Salzburg, which is likely to be one of the most trying courses the cars have ever traveled over at high speeds in a race.

The third day and second stage of the racing, from Bregenz to Salzburg, 226 miles, included the ascent and descent of the Arlberg, the road being over 5,000 feet above the sea at the summit of the pass. The event of the day was the finish of the Gordon Bennett at Innsbruck, which, deducting the distance of the procession through Switzerland, made the cup contest 379 miles of actual racing. De Kuyff led away on his 70-horsepower Panhard, only to be overhauled by Edge not very far from Innsbruck, the French champion having broken down. Both of them in fact, the same remark applies to all the competitors had a most exciting time in going down the Arlberg, as the roads were in a shocking condition, and the very steep and dangerous descents and sudden twists and bends of the road made driving at speed little less than a nightmare. The fastest time was made by Baron de Forest on his Mercedes – 4h. 39m. 50s. Next came Marcel Renault nearly an hour later, although he did fastest light car time, and the performance of the Baron de Forest, considering the course, was nothing less than remarkable. The third man was Henry Farman on his big Panhard, followed closely by Count Zborowski and Edmond. The fastest in the voiturette class was Guillaume, while Osmont did the best among the motorcycles, though his time was very poor.

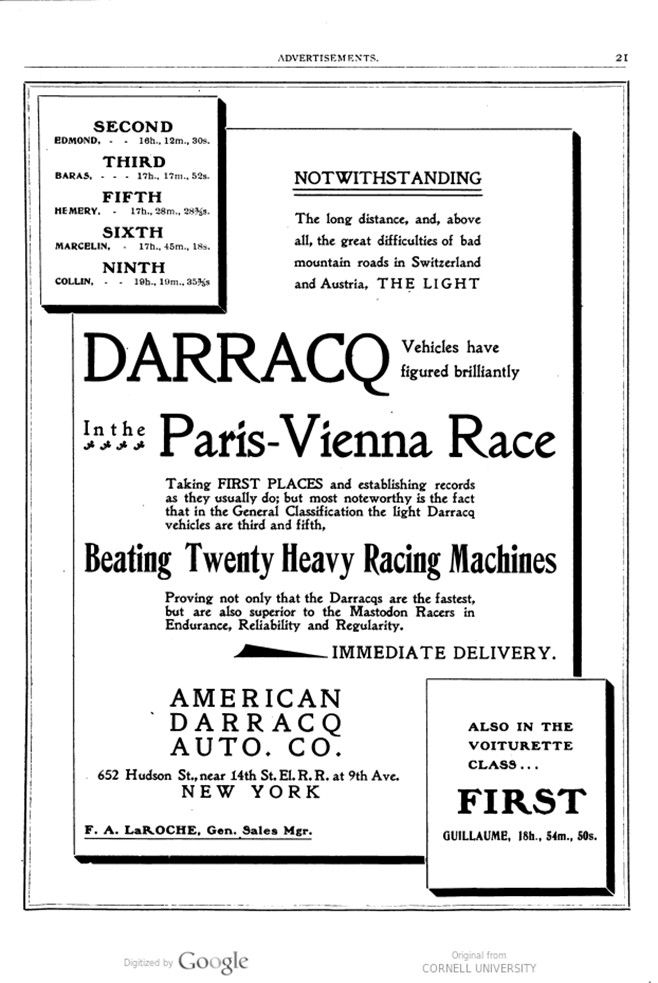

M. Marcel Renault, on his 16-horsepower light car, made the fastest time from Salzburg to Vienna (210 miles). He was followed by Baras, Zborowski, Emery, M. Farman and De Caters. The fastest net time – 5h. 15m. 5s. in the heavy car class was accomplished by Count Zborowski on the Mercedes, and M. Farman on the Panhard was 2m. later. Edge’s time for this section was eighth in the order of merit. In the light car section the Renault brothers were of course the first and second, as their times were fastest of the day irrespective of class, these being 4h. 40m. 7s. and 5h. 11m. 1s. In the voiturette class Guillaume, on a Darracq, finished first in 6h. 18m., while Osmont did best motorcycle time on his tricycle, occupying 7h. 40m. 54s. for the journey, and Bucquet, on a Werner, did fastest motor bicycle time, less than 2m. inside Osmont’s time. After the excitement of the previous day, the last stage was comparatively unexciting. The above times are without the neutralizations, as there was not time to work them out finally. At the last moment we learn by wire that it was officially declared two days after the finish that the fastest time (26h. 10m.) was accredited to M. Marcel Renault on his 16-horsepower light Renault. The second fastest time was Henry Farman’s, on the 70-horsepower Panhard – 26h. 34m. Mr. Farman consequently wins the 650 to 1,000 kilog. section, while M. Renault is the victor of the light car 450 to 650 kilog. section. The third fastest time goes to M. Edmond, who drove a 24-horsepower Darracq in 26h. 46m., and thereby takes second place in the light car section. M. Maurice Farman, on his 70-horsepower Panhard, 26h. 51m., and Count Zborowski, on his Mercedes, 26h. 58m., are fourth and fifth respectively. It would appear Zborowski did the fastest time, as he was penalized 40 minutes for an alleged infringement of one of the rules while passing through Switzerland, but until we have details of the matter it is impossible to say whether he really did the fastest time. or not, though it would appear his actual racing time was the best, as the Swiss section was not a speed trial. Guillaume, on a Darracq, won the voiturette section. The first place among the tricycles goes to Osmont, while Bucquet, on the Werner, took the first place among the motor bicycles, and the second position was also obtained by a machine of the same make, all or nearly all the other bicycles failing to stand the tremendous strain.

– The Autocar.

—————

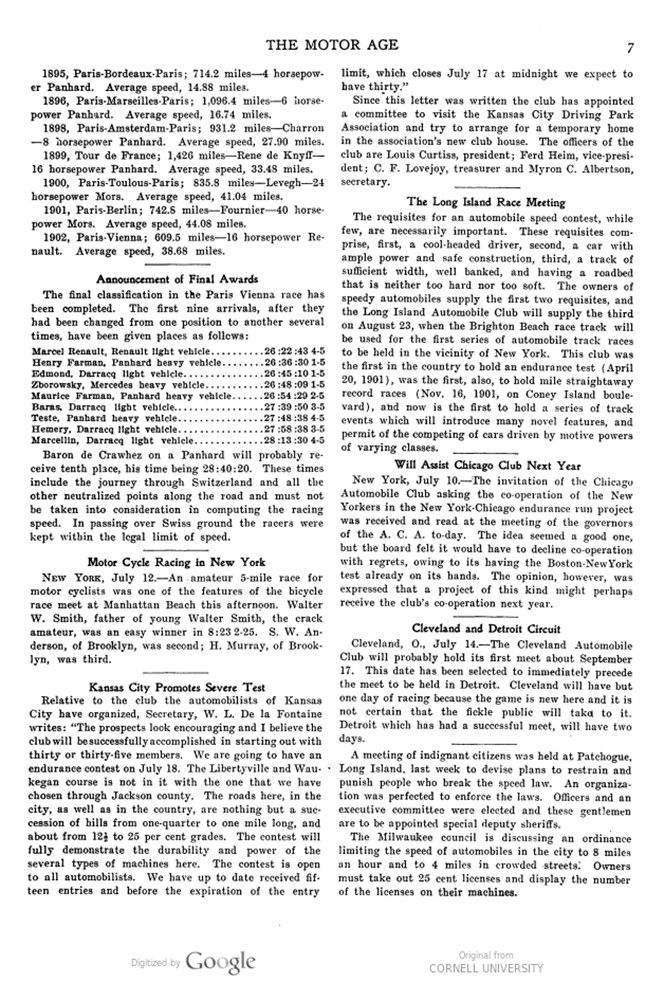

Record of Eight Years‘ Racing

The following table, showing the winners, distances and times of the great European road races since 1895 is interesting as indicating the improvement in vehicles in the interval:

1895, Paris-Bordeaux-Paris; 714.2 miles – 4 horsepower Panhard. Average speed, 14.88 miles.

1896, Paris-Marseilles-Paris; 1,096.4 miles – 6 horsepower Panhard. Average speed, 16.74 miles.

1898, Paris-Amsterdam-Paris; 931.2 miles – Charron – 8 horsepower Panhard. Average speed, 27.90 miles.

1899, Tour de France; 1,426 miles – Rene de Knyff – 16 horsepower Panhard. Average speed, 33.48 miles.

1900, Paris-Toulouse-Paris; 835.8 miles – Levegh – 24 horsepower Mors. Average speed, 41.04 miles.

1901, Paris-Berlin; 742.8 miles – Fournier – 40 horsepower Mors. Average speed, 44.08 miles.

1902, Paris-Vienna; 609.5 miles – 16 horsepower Renault. Average speed, 38.68 miles.

—————

Announcement of Final Awards

The final classification in the Paris Vienna race has been completed. The first nine arrivals, after they had been changed from one position to another several times, have been given places as follows:

Marcel Renault, Renault light vehicle…….. 26:22:43 4-5

Henry Farman, Panhard heavy vehicle…… 26:36:30 1-5

Edmond, Darracq light vehicle………………. 26:45:10 1-5

Maurice Farman, Panhard heavy vehicle.. 26:48:09 1-5

Zborowsky, Mercedes heavy vehicle……… 26:54:29 2-5

Baras, Darracq light vehicle………………….. 27:39:50 3-5

Teste, Panhard heavy vehicle………………. 27:48:38 4-5

Hemery, Darracq light vehicle………………. 27:58:38 3-5

Marcellin, Darracq light vehicle……………… 28:13:30 4-5

Baron de Crawhez on a Panhard will probably receive tenth place, his time being 28:40:20. These times include the journey through Switzerland and all the other neutralized points along the road and must not be taken into consideration in computing the racing speed. In passing over Swiss ground the racers were kept within the legal limit of speed.

Photos.

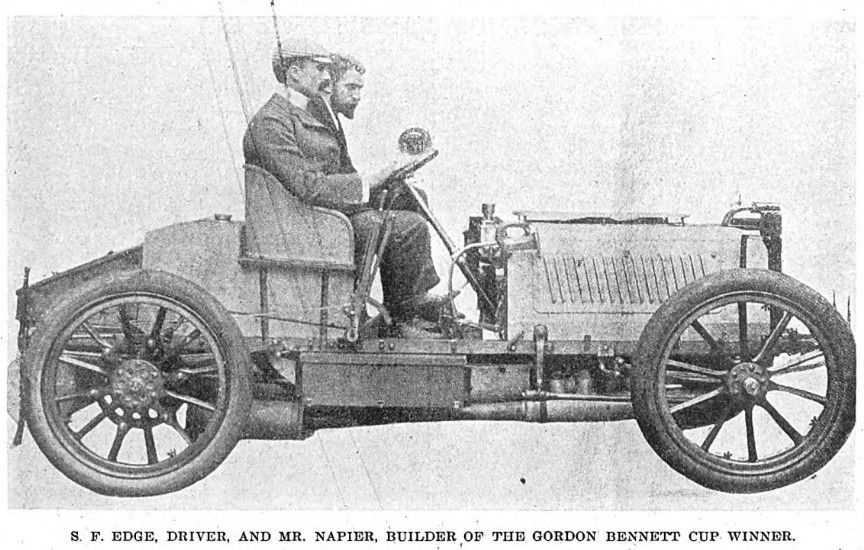

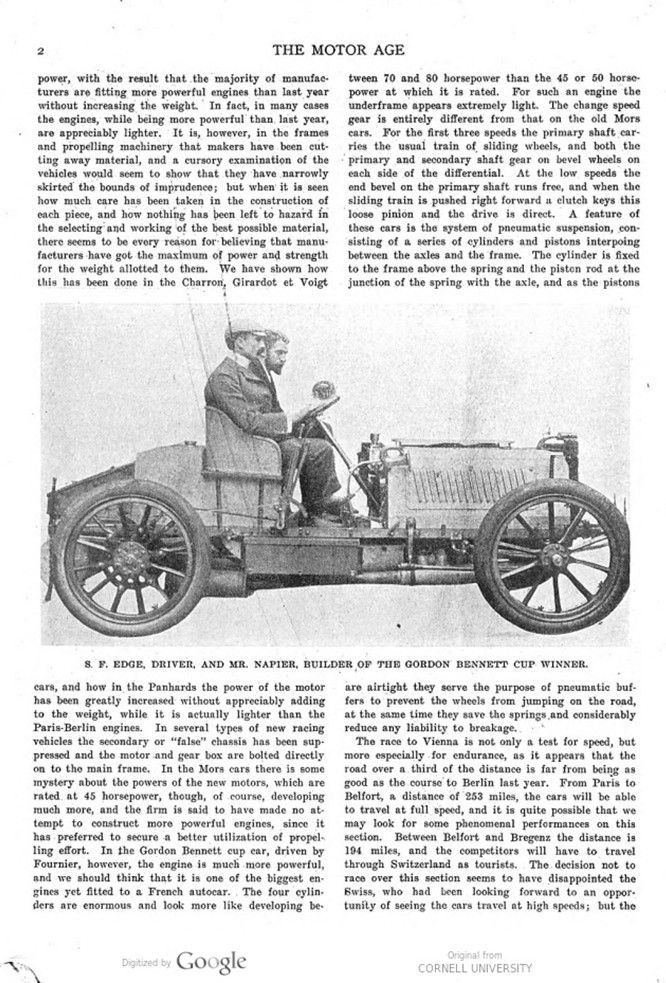

Page 1. S. F. EDGE, DRIVER, AND MR. NAPIER, BUILDER OF THE GORDON BENNETT CUP WINNER.

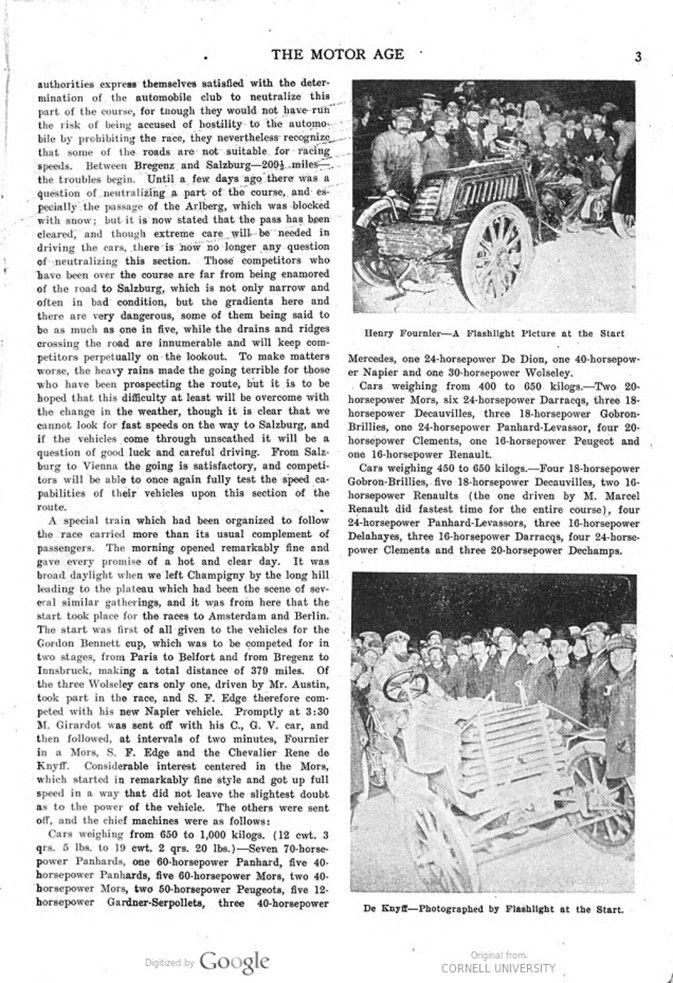

Page 2. Henry Fournier-A Flashlight Picture at the Start – De Knyff , Photographed by Flashlight at the Start.

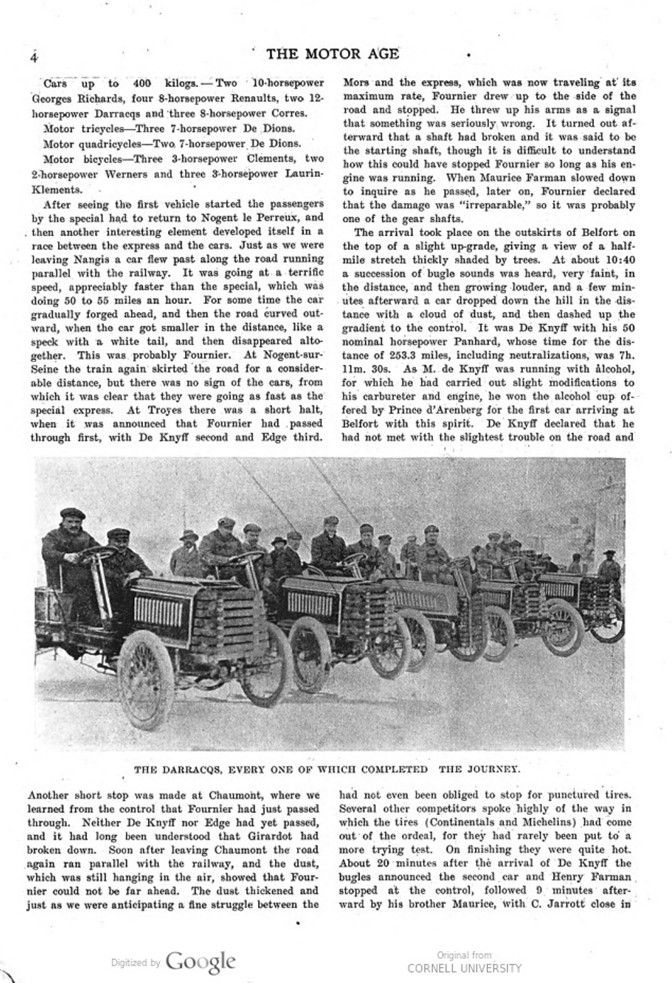

Page 3. THE DARRACQS, EVERY ONE OF WHICH COMPLETED THE JOURNEY.

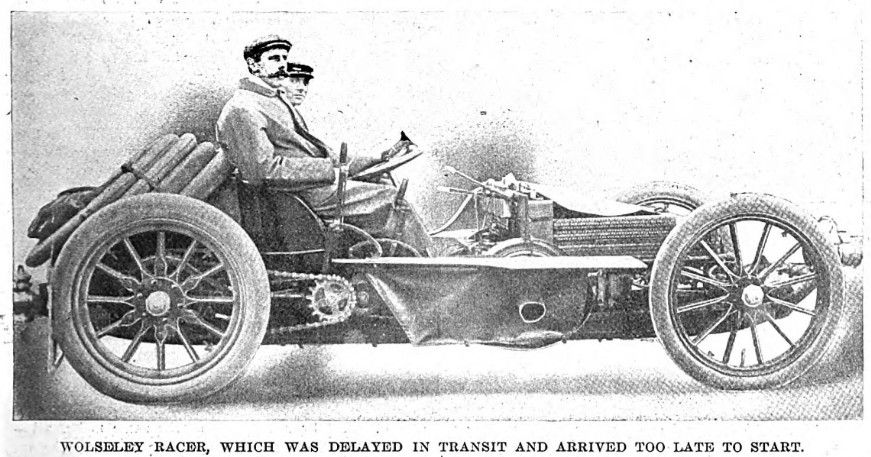

Page 4. WOLSELEY RACER, WHICH WAS DELAYED IN TRANSIT AND ARRIVED TOO LATE TO START.

Page 5. THE START AT CHAMPIGNY. – LOOKING TOWARD AND FROM THE STARTING POINT.