In the May 25 issue of Motor Age, several motor racing related articles were published just before the start of the Indianapolis 500-mile race. In this one, the American race drivers were mentioned, stating that the all American Crop of racing drivers was one to reckon with.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Motor Age, Vol. XIX, No. 21, May 25, 1911

The Making of the Race Driver – The American Crop

By C. G. Sinsabaugh

IT REQUIRED the publication of the entry list for the 500-mile race which takes place at Indianapolis next Tuesday to make the motoring public realize that the present crop of American racing drivers is of high-class caliber and that in the climb to the top of the ladder, which is symbolical of fame in the sporting sense, America has outstripped Europe, its teacher. An unbiased study of the world’s racing situation cannot help but convince everyone that the Yankee drivers, taking them as a whole, far outclass their brethren on the other side of the ocean. They possess the daring which is so essential to success in this profession; they can claim mechanical knowledge of the highest caliber; and they drive cars of American manufacture that possess stamina and speed equal, if not superior, to the foreign product. That this combination is a winning one is shown by the record table of the world, for no longer do the foreign drivers wear all the laurel wreaths as they used to do in the earlier days of the sport.

America owns all the world’s straightaway records, including the blue ribbon, Burman’s mile in :25.4, which is equal to 141 miles an hour; America owns all the dirt track marks of value.

And when it comes to speed honors, it can claim more than an equal division of the spoils. About all that stands to the credit of the foreigners are the exceptional times made at Brooklands, in England, by Hemery and Edge, and in this instance the track, more than the driver or car, was the important factor. Given a track in this country banked high enough to stand the terrific speed at which Hemery traveled when he smashed the short distance marks, and Burman or some other American pilot undoubtedly could beat them. In the case of Edge’s great 24-hour mark of 1,581 miles 1,310 yards, that does not look so wonderful as it did a couple of years back.

Already in this country 1,491 miles has been made in the journey twice around the clock, a performance which can be compared favorably with Edge’s efforts, for two reasons. The first is that it was made in actual competition, with the winner having to continually weave his way through a field of ten or twelve cars; and, second, because the track on which it was made only was 1 mile in circumference, as compared with the 2¾-mile oval at Brooklands. True, it was a foreign car, a Fiat, that put up this startling performance, but it must not be forgotten that the runner-up was a car of American manufacture, a 30-horsepower Cadillac, which reeled of 1,448 miles and did it without mechanical mishap. If a 30-horsepower car can come within 133 miles of Edge’s record and do it in a race, it stands to reason that a special time trial by a higher powered American car would topple over the mark made by Edge in 1907.

Speed on the Road

Passing on to the road racing department, it is discovered that here the American driver is making heavy inroads. There have been thirty-one road races won at better than mile-a-minute speed in the history of the world’s sport, and of this number twenty of them have been run in this country. Sixteen of the twenty drivers have been American, while fourteen of the winning cars were made in Yankee factories.

America has made this climb to the top by dint of perseverance and an improvement of the motor product which has put the Yankee car on a par with the foreign makes. In the days when the Gordon Bennett cup race was symbolical of the world’s speed championship America cut a sorry figure, indeed. Several times Americans crossed the Atlantic to strive for road racing supremacy with the foreign flock, but each time it proved a sorry quest for international honors. Year after year it was a foreign car and a foreign driver that lifted the cup, and America’s greatest boast so far as honors go in connection with the Bennett cup race was that in 1905 Herb Lytle in a Pope-Toledo actually finished the race, the first time an American ever caught the judges’ eyes at the end of the struggle in the Bennett Cup race.

It was the same story on our own soil in those days in connection with the Vanderbilt cup race. Foreign cars won in the earlier days of the cup struggle, and the names of Heath, Wagner and Hemery, which are inscribed on the big mug, tell of the futile struggles of the Yankee pilots. It was not until 1908, when George Robertson in a Locomobile trimmed the foreigners in this classic, that the tide turned in America’s favor. Harry Grant with the Alco followed it up with victories in 1909 and 1910, while another clincher was at Savannah last fall, when David Bruce-Brown won the American grand prix. In this instance it was a victory of an American driver instead of a Yankee car over the pick of the foreigners, for among Brown’s victims were the stars of the European racing world, Nazzaro, Wagner and Hemery, undoubtedly the greatest drivers Europe ever produced. This victory of the young millionaire placed America on an even footing with the foreigners, and from now on it is going to be a battle among the best pilots of the two continents for the world’s honors.

Within the past year or so American drivers have given more consideration to the science of the game of racing. They realize that a successful driver is born, not made, and that therefore America should have a better chance than Europe, for on this side of the Atlantic racing is at its zenith, while across the water the interest has lagged considerably within the last few years. Whether this will continue or not is problematical. France has dipped into the sport again, and its light-car race, which is scheduled for the latter part of June, has attracted an astonishing entry list, which promises something for the revival of the sport there, while the entry of three American cars, two Nationals and a Marquette-Buick, into the French grand prix, which is to be run July 9, may have considerable bearing on the situation as promising an invasion of Europe by American manufacturers, which may cause foreign makers to race in order to stall off the enemy.

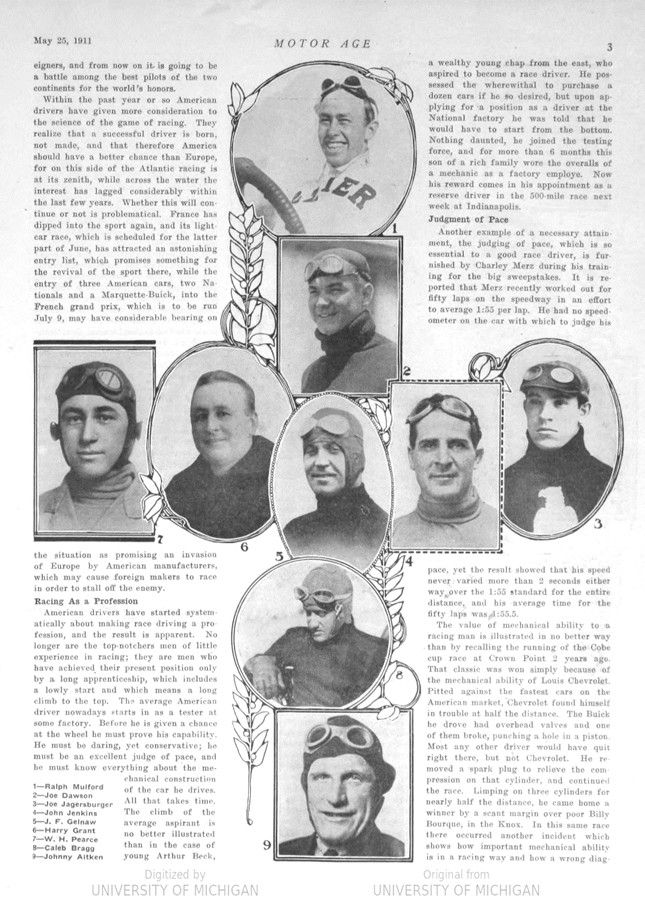

Racing As a Profession

American drivers have started systematically about making race driving a profession, and the result is apparent. No longer are the top-notchers men of little experience in racing; they are men who have achieved their present position only by a long apprenticeship, which includes a lowly start and which means a long climb to the top. The average American driver nowadays starts in as a tester at some factory. Before he is given a chance at the wheel he must prove his capability. He must be daring, yet conservative; he must be an excellent judge of pace, and he must know everything about the mechanical construction of the car he drives. All that takes time. The climb of the average aspirant is no better illustrated than in the case of young Arthur Beck, a wealthy young chap from the east, who aspired to become a race driver. He possessed the where withal to purchase a dozen cars if he so desired, but upon applying for a position as a driver at the National factory he was told that he would have to start from the bottom. Nothing daunted, he joined the testing force, and for more than 6 months this son of a rich family wore the overalls of a mechanic as a factory employe. Now his reward comes in his appointment as a reserve driver in the 500-mile race next week at Indianapolis.

Judgment of Pace

Another example of a necessary attainment, the judging of pace, which is so essential to a good race driver, is furnished by Charley Merz during his training for the big sweepstakes. It is reported that Merz recently worked out for fifty laps on the speedway in an effort to average 1:55 per lap. He had no speedometer on the car with which to judge his pace, yet the result showed that his speed never varied more than 2 seconds either way over the 1:55 standard for the entire distance, and his average time for the fifty laps was 1:55.5.

The value of mechanical ability to a racing man is illustrated in no better way than by recalling the running of the Cobe cup race at Crown Point 2 years ago. That classic was won simply because of the mechanical ability of Louis Chevrolet. Pitted against the fastest cars on the American market, Chevrolet found himself in trouble at half the distance. The Buick he drove had overhead valves and one of them broke, punching a hole in a piston. Most any other driver would have quit right there, but not Chevrolet. He removed a spark plug to relieve the compression on that cylinder, and continued the race. Limping on three cylinders for nearly half the distance, he came home a winner by a scant margin over poor Billy Bourque, in the Knox. In this same race there occurred another incident which shows how important mechanical ability is in a racing way and how a wrong diagnosis may bring about defeat. One of the contestants had gained an apparently safe lead and looked to have the race cinched, when ignition trouble developed. The driver thought it was the magneto, and although he was told by a pit attendant that it was something else he persisted in changing the magneto. In doing this he lost his big lead and never was a factor in the battle after that. If he had heeded the tip the trouble could have been cured in a minute or so. That this wrong diagnosis hurt the sport to a certain extent is proven, because the defeat brought about the retirement from the racing game of a concern that had been one of the strongest supporters motor racing ever had in this country.

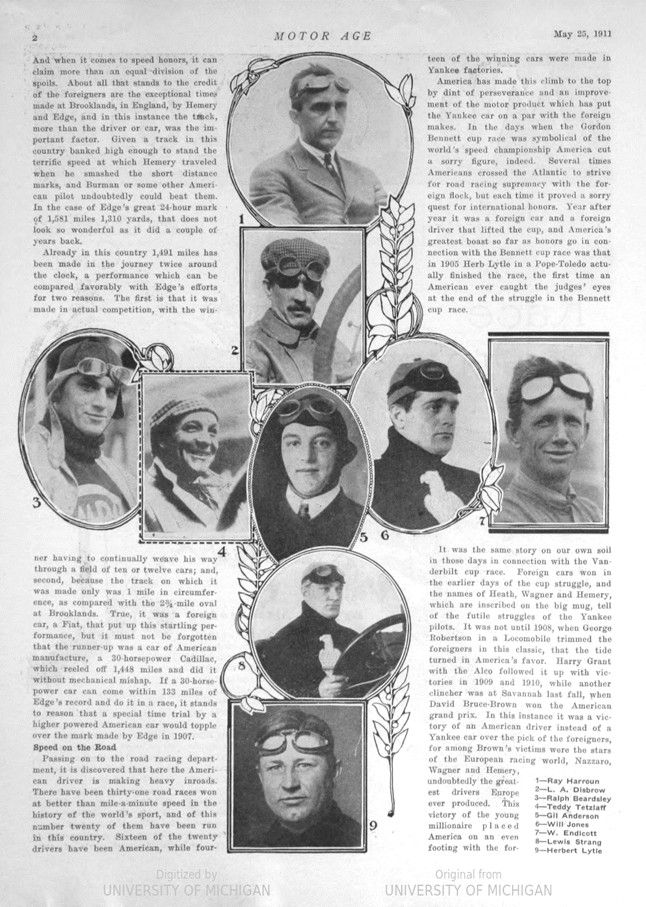

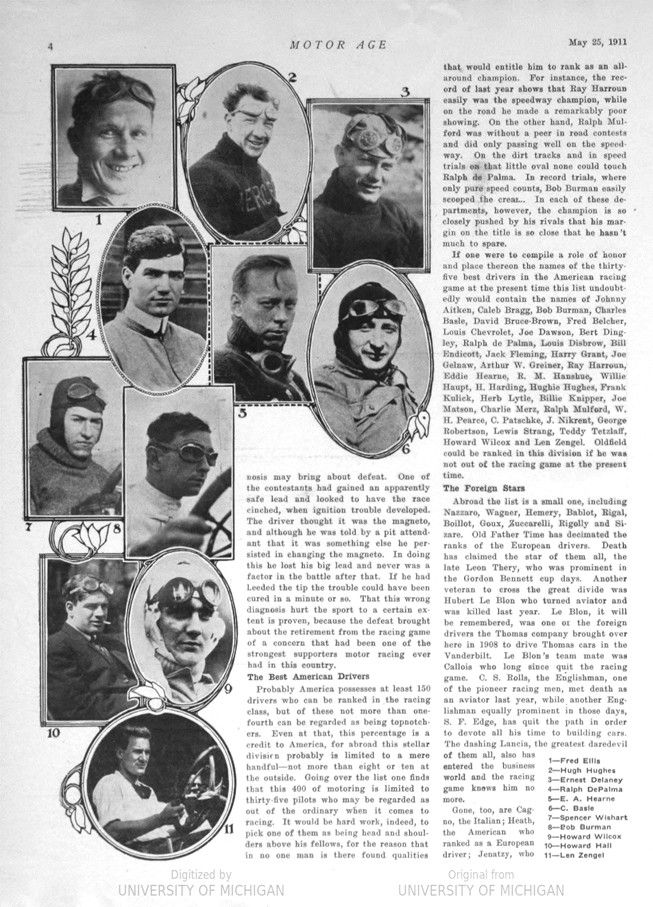

The Best American Drivers

Probably America possesses at least 150 drivers who can be ranked in the racing class, but of these not more than one-fourth can be regarded as being topnotchers. Even at that, this percentage is a credit to America, for abroad this stellar division probably is limited to a mere handful — not more than eight or ten at the outside. Going over the list one finds that this 400 of motoring is limited to thirty-five pilots who may be regarded as out of the ordinary when it comes to racing. It would be hard work, indeed, to pick one of them as being head and shoulders above his fellows, for the reason that in no one man is there found qualities that would entitle him to rank as an all-around champion. For instance, the record of last year shows that Ray Harroun easily was the speedway champion, while on the road he made a remarkably poor showing. On the other hand, Ralph Mulford was without a peer in road contests and did only passing well on the speedway. On the dirt tracks and in speed trials on that little oval none could touch Ralph de Palma. In record trials, where only pure speed counts, Bob Burman easily scooped the cream. In each of these departments, however, the champion is so closely pushed by his rivals that his margin on the title is so close that he hasn’t much to spare.

If one were to compile a role of honor and place thereon the names of the thirty- five best drivers in the American racing game at the present time this list undoubtedly would contain the names of Johnny Aitken, Caleb Bragg, Bob Burman, Charles Basle, David Bruce-Brown, Fred Belcher, Louis Chevrolet, Joe Dawson, Bert Dingley, Ralph de Palma, Louis Disbrow, Bill Endicott, Jack Fleming, Harry Grant, Joe Gelnaw, Arthur W. Greiner, Ray Harroun, Eddie Hearne, R. M. Hanshue, Willie Haupt, H. Harding, Hughie Hughes, Frank Kulick, Herb Lytle, Billie Knipper, Joe Matson, Charlie Merz, Ralph Mulford, W. H. Pearce, C. Patschke, J. Nikrent, George Robertson, Lewis Strang, Teddy Tetzlaff, Howard Wilcox and Len Zengel. Oldfield could be ranked in this division if he was not out of the racing game at the present time.

The Foreign Stars

Abroad the list is a small one, including Nazzaro, Wagner, Hemery, Bablot, Rigal, Boillot, Goux, Zuccarelli, Rigolly and Sizare. Old Father Time has decimated the ranks of the European drivers. Death has claimed the star of them all, the late Leon Thery, who was prominent in the Gordon Bennett cup days. Another veteran to cross the great divide was Hubert Le Blon who turned aviator and was killed last year. Le Blon, it will be remembered, was one or the foreign drivers the Thomas company brought over here in 1908 to drive Thomas cars in the Wanderbilt, Le Blon’s team mate was Callois who long since quit the racing game. C. S. Rolls, the Englishman, one of the pioneer racing men, met death as an aviator last year, while, another Englishman equally prominent in those days, S. F. Edge, has quit the path in order to devote all his time to building cars. The dashing Lancia, the greatest daredevil of them all, also has entered the business world and the racing game knows him no more.

Gone, too, are Cageno, the Italian; Heath, the American who ranked as a European driver; Jenatzy, who looked like Mephistopheles; Jarrott, of England, and Hanriot, Fournier and Farmam, the Frenchmen. Jenatzy is not lost altogether, for he once in a while returns to the racing game just to show that he is as clever as of yore, which fact was demonstrated last summer when he put up several remarkable performances in French hill climbs and road trials. Lautenschlager, the German who won the last French grand prix in 1908, only was a flash in the pan. and since that one big victory no one has heard of him on this side of the water. Fiery little Szisz, once one of France’s best, has quit for keeps.

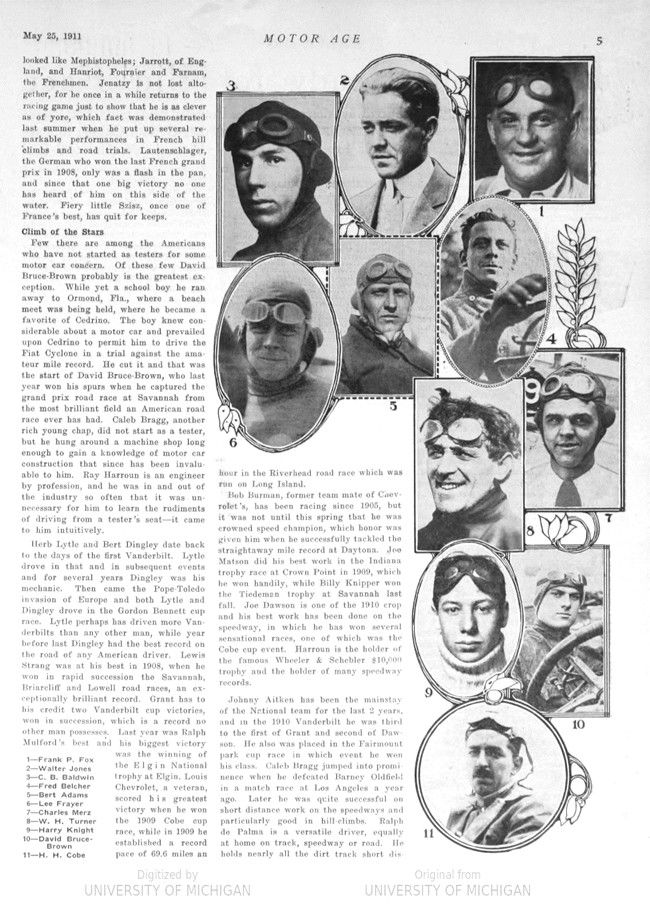

Climb of the Stars

Few there are among the Americans who have not started as testers for some motor car concern. Of these few David Bruce-Brown probably is the greatest exception. While yet a school boy he ran away to Ormond, Fla., where a beach meet was being held, where he became a favorite of Cedrino. The boy knew considerable about a motor car and prevailed upon Cedrino to permit him to drive the Fiat Cyclone in a trial against the ama- teur mile record. He cut it and that was the start of David Bruce-Brown, who last year won his spurs when he captured the grand prix road race at Savannah from the most brilliant field an American road race ever has had. Caleb Bragg, another rich young chap, did not start as a tester, but he hung around a machine shop long enough to gain a knowledge of motor car construction that since has been invaluable to him. Ray Harroun is an engineer by profession, and he was in and out of the industry so often that it was unnecessary for him to learn the rudiments of driving from a tester’s seat — it came to him intuitively.

Herb Lytle and Bert Dingley date back to the days of the first Vanderbilt. Lytle drove in that and in subsequent events and for several years Dingley was his mechanic. Then came the Pope-Toledo invasion of Europe and both Lytle and Dingley drove in the Gordon Bennett cup race. Lytle perhaps has driven more Vanderbilts than any other man, while year before last Dingley had the best record on the road of any American driver. Lewis Strang was at his best in 1908, when he won in rapid succession the Savannah, Briarcliff and Lowell road races, an exceptionally brilliant record, Grant has to his credit two Vanderbilt cup victories, won in succession, which is a record no other man possesses. Last year was Ralph Mulford’s best and his biggest victory was the winning of the Elgin National trophy at Elgin. Louis Chevrolet, a veteran, scored his greatest victory when he won the 1909 Cobe cup race, while in 1909 he established a record pace of 69.6 miles an hour in the Riverhead road race which was run on Long Island.

Bob Burman, former team mate of Chevrolet’s, has been racing since 1905, but it was not until this spring that he was crowned speed champion, which honor was given him when he successfully tackled the straightaway mile record at Daytona. Joe Matson did his best work in the Indiana trophy race at Crown Point in 1909, which he won handily, while Billy Knipper won the Tiedeman trophy at Savannah last fall. Joe Dawson is one of the 1910 crop and his best work has been done on the speedway, in which he has won several sensational races, one of which was the Cobe cup event. Harroun is the holder of the famous Wheeler & Schebler $10,000 trophy and the holder of many speedway records.

Johnny Aitken has been the mainstay of the National team for the last 2 years, and in the 1910 Vanderbilt he was third to the first of Grant, and second of Dawson. He also was placed in the Fairmount park cup race in which event he won his class, Caleb Bragg jumped into prominence when he defeated Barney Oldfield in a match race at Los Angeles a year ago. Later he was quite successful on short distance work on the speedways and particularly good in hill-climbs, Ralph de Palma is a versatile driver, equally at home on track, speedway or road. He holds nearly all the dirt track short distance records, while his name figures quite promiently in the speedway tables.

Eddie Hearne is one of those youngsters who started with a bank roll that jumped . him into the driver’s seat without the necessity of taking the tester’s course. He is the holder of the Indianapolis speedway helmet in which event he scored sensationally by averaging 86.37 miles per hour for 15 miles. Bill Endicott won the Massapequa trophy at the Vanderbilt meet last fall and preceding that he did well in the small-car events at Los Angeles in the spring of 1910. Wilcox promises to be one of the greatest of American drivers, although he only has been in the limelight for the past year. He is one of the crop of Indianapolis stars, which includes Aitken, Dawson and Merz. Gelnaw and Pearce are two Chicagoans who are consistent performers, the former winning the Wheatley Hills cup on Long Island last fall with Pearce being the runner-up. Gelnaw also won the Coca Cola cup at the Atlanta speedway last year.

Three Stars Killed

When the curtain goes up on the opening day of the racing season next Tuesday, it will be discovered that three of the old favorites are missing, all of them victims of the grim reaper. Death has claimed Tom Kincade, Al Livingstone, and Tobin De Hymel. Kincade was killed while training on the Indianapolis speedway last July, while Livingstone, winner of the Illinois cup at Elgin, met death at Atlanta while training for the speedway events there. De Hymel, one of the most promising of the younger generation of drivers, was killed on a dirt track in Texas while driving in a handicap race.