Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Motor Age, Vol. VI, No. 10, September 8, 1904

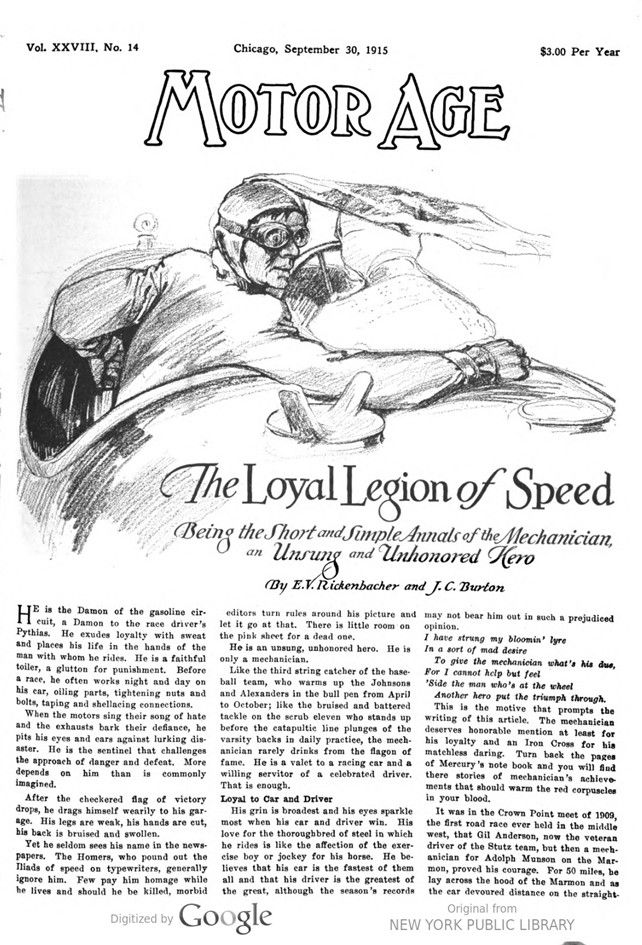

The Loyal Legion of Speed

Being the Short and Simple Annals of the Mechanician, Unsung and Unhonored Hero

By E.V. Rickenbacher and J.C. Burton

HE is the Damon of the gasoline circuit, a Damon to the race driver’s Pythias. He exudes loyalty with sweat and places his life in the hands of the man with whom he rides. He is a faithful toiler, a glutton for punishment. Before a race, he often works night and day on his car, oiling parts, tightening nuts and bolts, taping and shellacing connections.

When the motors sing their song of hate and the exhausts bark their defiance, he pits his eyes and ears against lurking disaster. He is the sentinel that challenges the approach of danger and defeat. More depends him than is commonly imagined.

After the checkered flag of victory drops, he drags himself wearily to his garage. His legs are weak, his hands are cut, his back is bruised and swollen.

Yet he seldom sees his name in the newspapers. The Homers, who pound out the Iliads of speed on typewriters, generally ignore him. Few pay him homage while he lives and should he be killed, morbid editors turn rules around his picture and let it go at that. There is little room on the pink sheet for a dead one.

He is an unsung, unhonored hero. He is only a mechanician.

Like the third string catcher of the baseball team, who warms up the Johnsons and Alexanders in the bull pen from April to October; like the bruised and battered tackle on the scrub eleven who stands up before the catapultic line plunges of the varsity backs in daily practice, the mechanician rarely drinks from the flagon of fame. He is a valet to a racing car and a willing servitor of a celebrated driver.

That is enough.

Loyal to Car and Driver

His grin is broadest, and his eyes sparkle most when his car and driver win. His love for the thoroughbred of steel in which he rides is like the affection of the exercise boy or jockey for his horse. He believes that his car is the fastest of them all and that his driver is the greatest of the great, although the season’s records may not bear him out in such a prejudiced opinion.

I have strung my bloomin‘ lyre

In a sort of mad desire

To give the mechanician what’s his due,

For I cannot help but feel

‚Side the man who’s at the wheel

Another hero put the triumph through.

This is the motive that prompts the writing of this article. The mechanician deserves honorable mention at least for his loyalty and an Iron Cross for his matchless daring. Turn back the pages of Mercury’s note book and you will find there stories of mechanician’s achievements that should warm the red corpuscles in your blood.

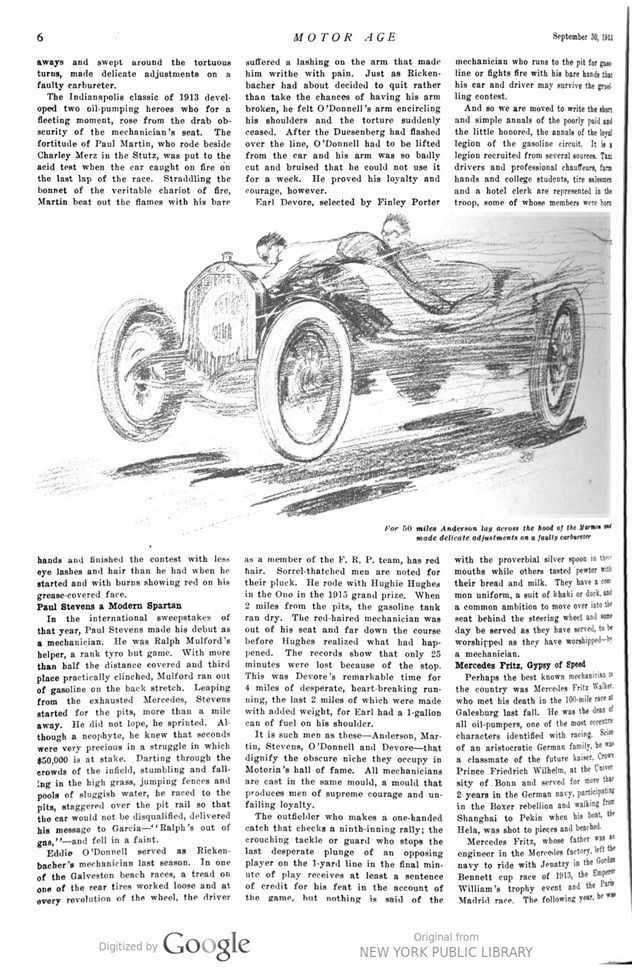

It was in the Crown Point meet of 1909, the first road race ever held in the middle west, that Gil Anderson, now the veteran driver of the Stutz team, but then a mechanician for Adolph Munson on the Marmon, proved his courage. For 50 miles, he lay across the hood of the Marmon and as the car devoured distance on the straightaways and swept around the tortuous turns, made delicate adjustments on a faulty carbureter.

The Indianapolis classic of 1913 developed two oil-pumping heroes who for a fleeting moment, rose from the drab obscurity of the mechanician’s seat. The fortitude of Paul Martin, who rode beside Charley Merz in the Stutz, was put to the acid test when the car caught on fire on the last lap of the race. Straddling the bonnet of the veritable chariot of fire, Martin beat out the flames with his bare hands and finished the contest with less eye lashes and hair than he had when he started and with burns showing red on his grease-covered face.

Paul Stevens a Modern Spartan

In the international sweepstakes of that year, Paul Stevens made his debut as a mechanician. He was Ralph Mulford’s helper, a rank tyro but game. With more than half the distance covered and third place practically clinched, Mulford ran out of gasoline on the back stretch. Leaping from the exhausted Mercedes, Stevens started for the pits, more than a mile away. He did not lope, he sprinted. Although a neophyte, he knew that seconds were very precious in a struggle in which $50,000 is at stake. Darting through the crowds of the infield, stumbling and falling in the high grass, jumping fences and pools of sluggish water, he raced to the pits, staggered over the pit rail so that the car would not be disqualified, delivered his message to Garcia-Ralph’s out of gas,“ and fell in a faint.

Eddie O’Donnell served as Rickenbacher’s mechanician last season. In one of the Galveston beach races, a tread on one of the rear tires worked loose and at every revolution of the wheel, the driver suffered a lashing on the arm that made him writhe with pain. Just as Rickenbacher had about decided to quit rather than take the chances of having his arm broken, he felt O’Donnell’s arm encircling his shoulders and the torture suddenly ceased. After the Duesenberg had flashed over the line, O’Donnell had to be lifted from the car and his arm was so badly cut and bruised that he could not use it for a week. He proved his loyalty and courage, however.

Earl Devore, selected by Finley Porter as a member of the F. R. P. team, has red hair. Sorrel-thatched men are noted for their pluck. He rode with Hughie Hughes in the Ono in the 1915 grand prize. When 2 miles from the pits, the gasoline tank ran dry. The red-haired mechanician was out of his seat and far down the course before Hughes realized what had happened. The records show that only 25 minutes were lost because of the stop. This was Devore’s remarkable time for 4 miles of desperate, heart-breaking running, the last 2 miles of which were made with added weight, for Earl had a 1-gallon can of fuel on his shoulder.

It is such men as these – Anderson, Martin, Stevens, O’Donnell and Devore – that dignify the obscure niche they occupy in Motoria’s hall of fame. All mechanicians are cast in the same mould, a mould that produces men of supreme courage and unfailing loyalty.

The outfielder who makes a one-handed catch that checks a ninth-inning rally; the crouching tackle or guard who stops the last desperate plunge of an opposing player on the 1-yard line in the final minute of play receives at least a sentence of credit for his feat in the account of the game, but nothing is said of the mechanician who runs to the pit for gasoline or fights fire with his bare hands that his car and driver may survive the gruel ling contest.

And so we are moved to write the short and simple annals of the poorly paid and the little honored, the annals of the loyal legion of the gasoline circuit. It is a legion recruited from several sources. Taxi drivers and professional chauffeurs, farm hands and college students, tire salesmen and a hotel clerk are represented in the troop, some of whose members were born with the proverbial silver spoon in the mouths while others tasted pewter with their bread and milk. They have a common uniform, a suit of khaki or duck, and a common ambition to move over into the seat behind the steering wheel and someday be served as they have served, to be worshipped as they have worshipped – by a mechanician.

Mercedes Fritz, Gypsy of Speed

Perhaps the best-known mechanician in the country was Mercedes Fritz Walker. who met his death in the 100-mile race at Galesburg last fall. He was the dean of all oil-pumpers, one of the most eccentric characters identified with racing. Scion of an aristocratic German family, he was a classmate of the future kaiser, Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, at the University of Bonn and served for more than 2 years in the German navy, participating in the Boxer rebellion and walking from Shanghai to Pekin when his boat, the Hela, was shot to pieces and beached.

Mercedes Fritz, whose father was an engineer in the Mercedes factory, left the navy to ride with Jenatzy in the Gordon Bennett cup race of 1913, the Emperor William’s trophy event and the Paris Madrid race. The following year, he was selected to escort Foxhall Keene’s Mercedes across the Atlantic and pumped oil for the New York millionaire in the Vanderbilt cup races of 1904 and 1905.

A born mechanic and respected for his loyalty, the services of Mercedes Fritz were in great demand. He assisted in building Tracy’s Locomobile for the 1906 Vanderbilt, rode with Victor Hemery in the 1908 grand prize and pumped oil for Barney Oldfield, Erwin Bergdoll, Ralph Mulford, Eddie Rickenbacher and Billy Knipper before a fatal accident cut short his gypsy career.

Goetz Expert on Sundaes

From mixing ice cream sodas in his father’s drug store to riding with Ray Harroun in the yellow Marmon is the vocational switch made in 1909 by Harry Goetz, generally regarded as the master mechanician of them all and until the retirement of the Maxwell from racing in July, lord high valet of the black cars driven by Eddie Rickenbacher, Billy Maxwell and Tom Orr. He served his apprenticeship under an export tutor and learned his lessons well. As a consequence, he has few equals in diagnosing trouble in an emergency. He scents faults either before they develop, or it is too late to remedy them. He is careful and conscientious and perfects each part of his car as if victory depended on each separate unit. He is cool in every crisis, never losing his head. Combined with these virtues, he has the ideal build for a mechanic, being small and quick and weighing not more than 120 pounds.

Eddie O’Donnell, who served as mechanician for three seasons before he was elevated to the rank of driver at San Francisco this spring, is the Maud Muller of the loyal legion, having raked the hay on his father’s farm near Whitewater, Wis., before he left the cows and chickens and decided that working in the service department of the Mitchell company at Milwaukee “ was the life.“ Mort Roberts was O’Donnell’s patron and a roll of adhesive tape his talisman, Eddie’s foresight in having the tape in his pocket winning the Pabst trophy for the Duesenberg driver and binding the former farm hand to a permanent job as mechanician, for when Roberts had a commanding lead in the race, a gasoline line broke but O’Donnell repaired the connection in less time than it takes to tell about it.

Paul Frantzen, Medical Student

Paul Frantzen, who was hurled over the embankment of the Tacoma track with Billy Carlson and suffered fatal injuries, had a morbid wish satisfied. Like the western gun fighters of the California mining camps, he declared that he wanted to die with his boots on, that he wanted to go out while traveling at high speed in a racing car. The fates gratified that gruesome desire and snuffed out the life of one of the most promising mechanicians in the game.

Cupid was indirectly responsible for Frantzen being a mechanician. His sister was a sweetheart of Billy Carlson’s brother, and it was through the influence of his prospective relative by marriage that the speed-mad boy secured a position on the Maxwell team.

Had he lived, Frantzen someday would have been wealthy, for his father is a rich resident of San Diego, Cal. Frantzen was sent to a medical school, but the higher education did not take. Ile was more interested in motor car chassis than human skeletons and showed greater skill at mending broken springs than fractured bones. He left the clinic to become a professional motorcycle rider and in a race from Los Angeles to Phoenix, plunged over a cliff and was lost in the desert for 18 hours. He was found by Mexicans in a half-crazed condition as a result of a scalp wound and thirst.

The police of Milwaukee forced Louis Fontaine, Ralph de Palma’s mechanician, to take to the gasoline circuit for a livelihood. A chauffeur for Charles Pfeister, a wealthy resident of the city made famous by Schlitz and Sherby Becker, he was arrested so many times for speeding he decided to seek a realm where satisfying a desire for high velocity was not an offense punishable by fine.

Drove Vanderbilt Cup Lozier

Fontaine made his debut as a mechanician in the 1912 Vanderbilt cup race and rode with Nelson in the Lozier that Ralph Mulford piloted to victory in the same classic of the year previous. Nelson made such a poor showing that Fontaine was put at the wheel of the car in the grand prize 2 days later but he broke up before Bragg’s Fiat got the checkered flag. Last year he brought the Lozier to Elgin and failing to annex any of the prize money, came to the conclusion that he was better fitted to pump oil than drive. He formed a partnership with de Palma this spring and rode with the Italian at Indianapolis, Des Moines, Elgin and Minneapolis. Jack Gable, who sees that the motor of the Peugeot is getting enough gas and oil when Bob Burman runs wild, is an expert mechanic and a veteran in the loyal legion of speed. He was a machinist on the payroll of the Cutting Motor Car Co. and left his lathe to ride with Burman when Bob took the French car to the Cutting plant for an overhaul last summer. Gable has sat beside Victor Hemery and Felice Nazzaro and at one time was associated with Erwin Bergdoll, the wealthy Philadelphia driver who had a corps of mechanics working around his garage continually in his time and has furnished many financially embarrassed oil-pumpers with meal tickets.

Fred McCarthy, who sits at the good left hand of Dario Resta when the Peugeot barks a challenge at time, is a man of several trades. His home is in Brooklyn and he formerly worked in the White shops when the cars that bear the albatross nameplate were manufactured in New York. On the removal of the White company to Cleveland, McCarthy purchased a taxicab and took orders from the traffic cops and tips from the sun dodgers that throng the Gay White Way. Nightly pilgrimages up and down Broadway soon grew monotonous, however, and McCarthy accepted a position with the Braender Tire Co., first acting as New York salesman and then being promoted to general road man. While traveling about the country and spreading the gospel of Braender tires at various race meets, he became acquainted with the drivers and when Ralph Mulford took over the Peugeot for a campaign last summer, he persuaded McCarthy to ride with him. Thus, McCarthy became connected with the Peugeot Auto Import Co., which backed Mulford and now is paying the cost of Dario Resta’s triumphant invasion.

Tony Janette a Pioneer

Tony Janette is another mechanician who has honked at Broadway crowds from the seat of a taxicab. Tony hails from sunny Italy and came to this country with Louis Wagner for the 1906 Vanderbilt cup race. Louis returned to that dear France after failing to win the classic but Tony decided to remain in America. He had been told that the streets of New York were paved with gold but the first assay did not verify the promise of the prospectus. He determined to work the common claim, however, and found that the taxicab meter best served him for panning.

Janette soon was regarded as an authority on motor cars of exotic breeding. He made the New York headquarters of the Benz company his club and often was called into consultation by Benz owners whose machines were suffering from mysterious ailments. When Ernie Moross purchased the Blitzen Benz, he secured the expert services of Janette and Tony can boast of having groomed the famous car in which Barney Oldfield and Bob Burman rode to international fame and world’s records for speed on the sands of Daytona-Ormond.

Billy Chandler Taxi Artiste

Billy Chandler, who rode in the Lozier with Mulford when Smiling Ralph took the Vanderbilt cup at Savannah in 1911, also received gratuities from the taxicab patrons of New York before he invested himself in the khaki of Mercurian knighthood. Billy’s stand was at the corner of Forty-second street and Broadway, where George M. Cohan and Willie Collier are reputed to meet occasionally to exchange the gossip and pleasantries of the theatrical profession, and Chandler knew a large constellation of the dramatic stars well enough to call them by their first names.

Chandler drove a Lozier on his beat and became acquainted with Mulford through meeting him at the New York branch of the Lozier company. When Joe Horan was elevated to the rank of driver, Chandler asked Mulford for a job as mechanician and landed it.

Pete Henderson, who made his debut as a driver in the speedway race at Des Moines August 7, left the classic halls of Drake college to pump oil into the motor of a Mason. He is a Canadian by birth and in the off season, receives his mail at the post office at Fernie, B. C. He applied to Eddie Rickenbacher for a job when the Swiss driver was assisting Fred Duesenberg in building the Masons in 1913. Henderson’s light weight was a recommendation, and he had a personality that appealed to Baron Rick, but he was not of age and Duesenberg refused to take him on unless he first secured his father’s consent. Rickenbacher rendered first aid with pen, ink and paper, writing to Henderson pere who acceded to the request and made Rickenbacher his son’s speed guardian. Henderson first rode with George Mason, the most obese driver that ever stepped on the throttle of a racing car, and then pumped oil for Eddie O’Donnell when the latter got a mount.

Jack Henderson, Pete’s oldest brother, is a mechanician because he decided that his mother did not raise her boy to be a soldier. He was subject to military service in British Columbia but did not relish the idea of being a Tommy Atkins so ran away from home in February and joined the Duesenberg team in San Francisco. Tom Alley took a fancy to him and put him to work. At the present time, Jack is riding with Eddie O’Donnell. He showed his gameness in the 500-mile race at the Twin City speedway, holding a loose radius rod on the Duesenberg for the last century of the grueling grind over the wavy concrete track. He was so exhausted at the completion of the contest that he fainted and had to be helped out of the car.

Stevens a Hotel Clerk

Paul Stevens, who satisfies his desire for high speed by riding with Ralph Mulford, yells „Front!“ at lethargic bell boys when he is off duty and not serving as a mechanician. His father is proprietor of a hotel at Lake Placid in the heart of the Catskill mountains where for 2 or 3 weeks every summer, Mulford emulates Rip Van Winkle and flees from the nagging roar of the racing car that he has taken to spouse. Stevens was behind the clerk’s desk at the hotel when he first met the 1911 Vanderbilt cup winner. He confessed his heart’s ambition to travel at 100 miles an hour, and Mulford gave him an opportunity to achieve it in the Indianapolis classic of 1913.

Fibs and Lands a Job

If Jack Van Hoven, who pumped oil for Rickenbacher at Omaha and Sioux City this year, had not been such a good liar, he probably would not have had the chance to develop into such a good mechanician. Early last spring he falsified himself into a job in the racing car department of the Maxwell company. He told Harry Goetz that there was nothing he didn’t know about carbureters, magnetos, torque rods, cylinders and other parts of a machine. He talked so convincingly that Goetz believed him and took him on.

Van Hoven was guilty of some ludicrous blunders and when given the fourth degree, confessed that he had flirted with the truth in shameless fashion. As a punishment, he was put in the pits to take charge of the tire changes, the hardest and most thankless job on a racing team. The boy was game, however, and soon became a wizard in getting an old wheel off and a new wheel on a car.

After traveling with Ernie Moross‘ barnstorming troupe last season, Van Hoven went to Chicago and secured a position as chauffeur from P. D. Armour III, driving the grandson of the famous packer through Hawaii on a winter tour. This spring he went back on the Maxwell team and was promoted to relief mechanic.

Sioux City is Van Hoven’s home. His mother, a widow, is quite wealthy and he himself owns considerable property. Unlike the majority of mechanicians, he is not fastidious about his dress and about the last thing he will spend money for is clothes. When asked why he did not wear silk shirts, Panama hats, made-to-order suits and hand-sewed shoes, he replied: „Why should I doll up? This racing suit makes the big hit with me.“

Barney Oldfield’s fides Achates, George Hill, is driving on the Pacific coast and Harold Dashbach now is inhaling the aroma of the veteran’s cigars. Hill, who is a product of the Los Angeles‘ garages, worked for the company that sold Oldfield a Mercer and Barney took a fancy to him. Barney also took orders from him, for Hill proved to be a dictatorial person and bossed the boss in a way that was little short of lese majesty. Oldfield admired him for it, however, and ate out of his mechanician’s hand without biting it off.

Before the Vanderbilt cup and grand prize road races were run at San Francisco, Dashbach was driving a tire service car. He helped to prepare Resta’s Peugeot for the two classics and worked in the Peugeot pit. He went to New York with the Peugeot outfit and was to have ridden with Frank Galvin at Indianapolis, but Galvin’s car did not qualify and Dashbach watched the victory of de Palma from the pits. He first pumped oil for Oldfield at Tacoma.

Basso an Expert on Fiats

Domonic Basso, who traveled with the Maxwell team as Teddy Tetzlaff’s helper, is one of the most picturesque members of the loyal legion. He is an Italian who came over to America with the 120-horsepower Fiats driven by Felice Nazzaro, Caleb Bragg and the late David Bruce-Brown in the 1911 grand prize. When E. E. Hewlett, the Los Angeles‘ sportsman, purchased one of the cars for Tetzlaff, Basso was included in the bill of sale. He rode to victory with Teddy in the world’s record Santa Monica race, pumped oil into the motor of the Isotta at Indianapolis in 1913 and took care of the Blitzen Benz for Moross last season. He was thrown from Tetzlaff’s Maxwell in practice for the 1914 dirt track event at Kalamazoo, sustaining a fractured skull, and has not ridden since.

Another mechanician of Italian birth is Roxy Pollatti, George Babcock’s helper. He is a native of Turin and worked under Babcock as a road tester for the Pope-Hartford company. When Harry Grant induced Babcock to take the wheel of the Sunbeam at Corona last year, the latter took faithful Roxy with him. Pollatti then joined the Maxwell team as relief mechanician but when Babcock got a Peugeot mount for Indianapolis, went back to his first boss.

Heine Ulbrecht’s First Race

Before he became a driver, Heine Ulbrecht was known around the racing camps as an expert mechanician. He not only was in charge of Louis Disbrow’s Zip and Jay-Eye-See but he served as valet to Bill Endicott’s pig. Heine made his debut as a driver in a meet at Denver where there is a half-mile track within a mile track with one home stretch for both courses. He had the biggest allowance in a handicap event in which Disbrow passed all the cars but Ulbrecht’s, and Heine won with yards to spare. At the conclusion of the race, he demanded of Alec Sloan, the team manager: „What did ya let all them touring cars on the track for?“ He had been driving the half-mile course.

Many of the greatest drivers in the game have served their apprenticeship in the school of speed as mechanicians. Eddie Rickenbacher rode with Lee Frayer in the 1906 Vanderbilt cup race. Ralph de Palma started his spectacular career as a humble helper of Al Campbell in practice for the 1907 Briarcliff trophy event. Campbell suffered a broken leg 2 days before the race and the Italian was substituted as pilot of the Allen-Kingston. Eddie Pullen, holder of the world’s road racing record of 87.86 miles per hour, pumped oil for Hughie Hughes. Jean Chassagne, noted the world over for his conquest of time and distance on the Brooklands‘ track, is a former Sunbeam mechanician. Joe Horan and Billy Chandler saw service under Ralph Mulford.

During the racing season, the life of a mechanician is one overhaul after another. Before each contest he must put the car in first-class shape. His driver relies on him to have the machine in the pink of condition-connections taped and shellacked, bolts and nuts cotter-pinned and all parts tight and well oiled.

While the race is in progress, the mechanician must be on the alert every second. He watches all four tires and keeps the driver posted on their condition. He pumps oil in the motor and air in the gas tank. He keeps his eye on overtaking cars. He receives the pit signals and relays them to the man with whom he rides. He assists the driver in taking on gas, oil and water and helps in making tire changes if more than one wheel is changed at a single stop. Should mechanical trouble develop, he must be able to diagnose the cause of the ailment immediately and make repairs, either with the assistance of the driver or single-handed.

Statistics for the past 10 years show that there have been three mechanicians killed for every one driver. Thus, it can be seen that the mechanician’s chances of injury are far greater than those of the man with whom he rides and, on whose judgment, and skill he must rely solely. It is usually the mechanician who is thrown first from a car and the man who is most seriously hurt in a spill. The driver has the steering wheel against which to brace himself in time of accident. The mechanician has nothing. Ile must gamble with injury and death. If the fates so decree, he lives; if not, he dies or is maimed.

In return for the long hours of labor he puts in and the chances he takes, the mechanician receives very small wages. His pay averages about $30 per week and in addition he usually receives 10 per cent of the prize money won. Of course, the more expert and more experienced the mechanician, the better the pay and a system of gradual promotion rules in the ranks of the loyal legion of speed, for as the mechanician proves his worth, he is given a seat on a better car with a better driver.

Like the jockey, the mechanician should be light. The ideal weight is about 120 pounds. Although a pygmy, he must be strong and quick, a man of good habits and able to think fast in an emergency. Above all else, the mechanician must have supreme confidence in his driver and be willing to labor night and day.

Yes, a mechanician leads a gay life, if you say it quick and with reverse English.

Photos captions.

Page 6.

For 50 miles Anderson lay across the hood of the Marmon and made delicate adjustments on a faulty carbureter.

Page 7.

Stevens raced to the pits, staggered over the pit rail, delivered his message to Garcia – „Ralph’s out of gas“ – and fell in a faint.

At Galveston, Eddie O’Donnell prevented Rickenbacher’s arm from being fractured by protecting the driver from a lashing caused by a loose tread on the rear tire.

Page 8.

Frantzen was more interested in motor car chassis than human skeletons and showed greater skill at mending broken springs than fractured bones.

Page 9.

The police of Milwaukee forced Louis Fontaine, Ralph de Palma’s mechanician, to take to the gasoline circuit for a livelihood.