Anticipating the Indianapolis 1915 Sweepstakes, this extended article first discusses the speedway history to date. A view of the track itself is followed by description on some of the participating cars, such as Sunbeams, Delages and Peugeots. The new and upcoming Stutz cars with their 16 overhead valves, overhead camshaft are described extensively, as well as the Stutz Team. Finally, drivers and officials come under the scope of attention.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

The Automobile Journal, Vol. 39, No. 8, May 25, 1915, page 12-24

THE FIFTH INDIANAPOLIS SWEEPSTAKES

Twenty-Five-Contestants Left by Elimination Trials

Smallest Motors in History of Great Classic Will Be Used by Leading American and Foreign Drivers.

WHEN the cars start on their long journeys in the Fifth Annual International Sweep- stakes on Saturday, May 29, the smallest field of contestants that has ever competed at Indianapolis will leap away from the starters‘ stand. The elimination trials have been particularly disastrous to the hopes of many drivers this year. Only 25 cars of the 41 entered survived, and of these, two have since been wrecked and may not be in shape to compete.

An exceptionally large number of new and revolutionary designs had been prepared for the contest, and several of these were found to be impossible to perfect in time even to appear for the trials. That happened to three Mercers, three F. R. P’s., three Bergdolls, a Du Chesneau and Ralph Mulford’s special car.

These cars represented radical attempts to make up by high engine speed the difference in cylinder size required by this year’s regulations, which have reduced the piston displacement of the cars by 150 cubic inches. The Mercers had 16 valves and were designed to turn over 3500 revolutions per minute, and the F. R. P’s. were of a striking Knight engine design, which was said to be capable of 5000 revolutions per minute.

Their absence from the race will not, however, reduce its interest. In Dario Resta, an Italian, bred in England, and driving a French Peugeot, Europe has a representative of the first rank. The best America could pit against him in the Grand Prize and the Vanderbilt Cup events early in the spring could not keep up with him. J. Porporato, an Italian driver of an English Sun- beam, is another European star. It will be his first American appearance.

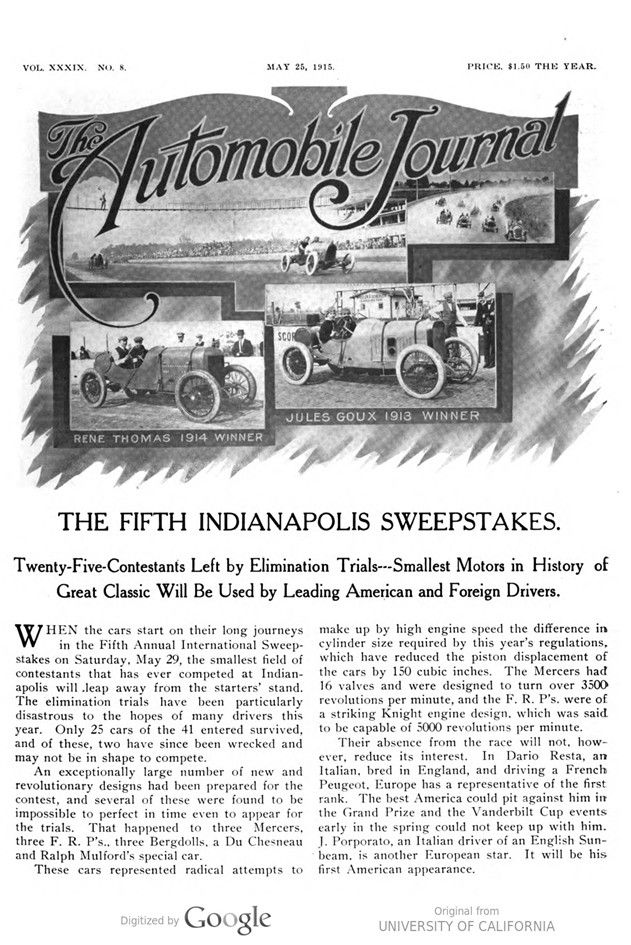

Most of the great American stars are in the race. Cooper, Wilcox and Anderson, the great Stutz combination, all qualified with flying colors. Ralph de Palma, in his Mercedes, made more than 98 miles per hour in the trials. Burman, who won the Oklahoma races, is there with his tried and trusted Peugeot. The three Maxwell drivers, Carlson, Rickenbacher and Tom Orr have qualified. Oldfield, whose Bugatti has been working badly, will drive a Sunbeam.

The small size of the cars adds interest to the race. In this the speedway officials have followed the general tendency of automobile design, which has produced constantly smaller and lighter cars.

No New European Designs.

During the year European engineers have been exclusively devoting themselves to the production of special vehicles for war uses and have not been able to develop anything new in racing cars. The European designs are the same as those of a year ago.

This year American engineers, for the first time, have very seriously devoted them- selves to the designing of racing machines. They started with the long experience of Europe before them. No expense has been spared.

In many of the American cars very expensive special alloys, which yield as much strength as iron and steel with. lighter weight, have been employed. They have been used in pistons, crankshafts, connecting rods and even in frames. Not only are many of these metals expensive in themselves, but they present difficulties in machining and finishing that are not encountered with more ordinary materials.

But light weight has become a matter of utmost importance in designing a car for the big race. Not only do the smaller engines in use make lighter weight an essential, but when the cars are going at rates of speed around 100 miles an hour, it is necessary that they should frequently slow down at the turns. When the turn is passed they must speed up again, and acceleration depends directly upon the weight of the car. While a heavy car might be equally successful in a straight away race, where no slowing up is necessary, smaller weight is essential on a curving track.

One of the many reasons why modern cars, with half the piston displacement of those made. four years ago, can make better speed, is that the greater piston speed of the engines enables them to burn nearly twice as much gas as was burned in the large, slow-moving motors. The power developed depends, other things being equal, on the amount of gas from which it is abstracted.

In 1911, when the first 500-mile race was run, and again in 1912, big-engined and heavy cars with piston displacements of 600 cubic inches were used. In 1913 and 1914 this was reduced to 450 inches, and this year it is 300 inches-engines just half the size of those used in 1911 and 1912.

The First Year’s Race.

The first year the 500-mile race was run the prizes offered by the Speedway company amounted to only $25,000. But that was sufficient to draw out a big field of very prominent entries. The international character of the event was not strong, however. For, while there were cars of three nations entered, two Benz and one Mercedes from Germany, two Fiats from Italy and 38 American cars, all of the drivers were American.

Ray Harroun won the first race, in his Marmon, in 6:42:08, averaging 74.65 miles per hour. D. Bruce-Brown, who was second, in a Lozier, averaged 74.29 miles per hour. Ralph Mulford, in a Fiat, covered the run at an average of 72.73 miles, and Spencer Wishart, in a Mercedes, at 72.65 miles. Twelve cars finished the race, and 13 more were still running when time was called. Harroun’s prizes amounted in all to $14,250. This is the smallest amount that any winner has ever taken in the big event.

In 1912, only 27 cars were entered. Nine finished and only one other was running when the race was called. Although 12 prizes had been offered by the Speedway management that year, it was possible to award only 10 of them on the showing of the cars. Germany was represented by a Mercedes, and Italy by a Fiat, but again the international character of the event was negligible. The prize money offered totalled $50,000.

Joseph Dawson won the race, driving a National 500 miles in 6:21:06, and averaging 78.73 miles per hour, which established at that time a world’s record for the distance and for most of the intermediate distances. Including the value of special trophies he won, Dawson’s share of the money amounted to $35,000. He was followed over the line by Teddy Tetzlaff, in a Fiat, with an average speed of 76.60. Hugh Hughes was third, in a Mercer, averaging 76.30, and Merz, in a Stutz, finished fourth, with an average speed of 76 miles per hour.

In 1913, 35 cars were entered, and 27 of them started. This time the international character of the event was much more marked, though American cars greatly predominated. There were five nations represented: Germany, by a Mercedes; Italy, by three Isottas; England, a Sunbeam, and France with two Peugeots. The remainder were American cars. France finished in first place, America, in second and third; England, fourth; Germany, fifth; America, sixth; Germany, seventh, and American cars took the remainder of the prizes.

Goux Takes the Big Prizes.

Jules Goux, the French Peugeot entrant, who took the 1913 race, finished the course in 6:35:05. This average time was 75.92 miles per hour. This was considerably less than the time of the year before, due no doubt to the reduction in engine size from 600 cubic inches piston displacement to 450 inches. His share of the prize money was about $35,000, substantially the same as Dawson’s in the year before.

Goux was followed across the tape by Spencer Wishart, in a Mercer, whose speed was 73.49 miles; Charles Mertz, Stutz, speed 73.38, and Albert Guyot, Sunbeam, 70.92 miles per hour.

In 1914 there were 48 cars entered. That number was reduced to 31 by the elimination trials. This time six countries were represented: America, with the majority of the cars, France, by three Peugeots and two Delages; Germany, by two Mercedes and one Bugatti; Italy, by an Isotta, and England, by a Sunbeam.

Rene Thomas, in a Delage, won the race in 6:03:45.99, and at an average speed of 82.47 miles per hour. This established a new world’s record for 500 miles and for all distances greater than 300 miles. The prize granted by the Speed- way amounted to $21,750, and a sufficient number of trophies were taken by the winner to make it $35,000 in all.

The European cars had it very much their own way. Thomas was followed by Duray, in a Peugeot, at a speed of 80.99 miles per hour; Guyot, in a Delage, speed 80.20 miles per hour, and Goux, in a Peugeot, speed 79.49 miles per hour. The first American to finish was Oldfield, in a Stutz, who came fifth with an average speed of 78.15 miles per hour, a rate almost equal to the speed of the winner the year before.

As will be seen by a glance at the accompanying table, every car in the race this year, except the Sunbeam six, is a four-cylinder. From the standpoint of design it is noticeable also that the overwhelming majority of the cars, both European and American, are equipped with wire wheels. Overhead valves also are the rule.

The three Maxwells, designed by Ray Harroun, winner of the 1911 500-mile race, and now chief engineer of the Maxwell Motor Company, are four-cylinder cars, with a bore of 334 inches and stroke of 634 inches and a piston displacement of 298 inches. The cars each weigh complete, 2200 pounds. They are equipped with Master carburetors, use Bosch double ignition, Rajah plugs, and are lubricated with castor oil. Houck wire wheels carry 32 by 4½-inch tires. They have left side drive and centre control.

The three Peugeots are similar to those that competed in last year’s race. Resta’s car is the one driven by George Boillot in the last Grand Prix of France. The cylinder dimensions are 92 mm. by 169 mm., and the piston displacement is 274 inches. In France it is known as a 4½ litre car. The other two Peugeots are what are known as three litre cars. The cylinder dimensions are 78 mm. by 156 mm., making a piston displacement of 183 cubic inches. These are similar cars to that driven by Duray in the Indianapolis race last year.

On the front of the motor is a short cross shaft driving a combined oil and air pump at one-third engine speed. Ordinarily this pump aspires pure air, and, through a pressure regulator, maintains a certain pressure on the lubricant tank set with the frame under the driver’s seat. This pressure drives the oil through a single feed pipe to the dash distributor, thence through five leads to the crank chamber, to the overhead cam- shafts and to the pump and magneto shafts in front. There is no provision for oiling the cylinder walls, except by the oil working out of the main bearings and kept in suspension within the motor. As soon as the oil returns to the base chamber it is drawn up and returned to the tank.

Another feature is the provision for taking up wear on the brakes while the car is travelling at high speed. Steel cables attached to the brake levers are brought through the frame and hooked on to short sliding sleeves on a tubular cross member. These sleeves are connected to a horizontal screw with left and right hand threads by means of which they can be brought closer together, thus shortening the length of the cable. The screw is just under the floor boards and can be reached by lifting a trap.

The Sunbeam driven by Grant is the only six- cylinder in the race. It has a cylinder displacement of 278 inches and is equipped with Silvertown cord tires and a Bosch magneto.

Sunbeams Have Glorious Past.

The Sunbeam fours, to be driven by Oldfield and Porporato, are similar in design to the racing cars by which a 12-hour record was established at the Brookland’s track in England of 89.95 miles per hour. Owing to the very short wheelbase, the transmission system has been redesigned and has only two forward speeds. It is carried on the same sub-frame as the engine and the whole arrangement is suspended at three points from the main frame. Two carburetors are used to assure ample gas supply.

As compared with the standard Sunbeam chassis, modifications in the oiling system have been adopted. The bulk of the oil, instead of being carried in the base chamber, is in a tank at the rear of the chassis, from which it is led to a pump in the base chamber by means of a large pipe. This pump forces the lubricant to all bearings, after which it returns to the base, when it is forced back into the tank by a secondary pump. This prevents the oil from being subjected too long to the heat in the crankcase.

Although none of the cars entered in the race has a weight of more than 2450 pounds, the little Cornelian, which Louis Chevrolet will drive, is the most sensationally light car. It weighs less than 1000 pounds. That is less than five times the weight of its driver.

This extreme light weight is attained by some new ideas in design. The car has no frame, and the weight between the axles is carried on a bridge formed by the shell of the sheet steel body. A remarkable streamline body is produced without angles or corners, and the construction is said to be amply strong.

The seat, both bottom and back, is suspended entirely free from the sides of the car on two long. half-elliptic springs, which produces very remarkable riding qualities. The motor is a four-cylinder, cooled by thermo-syphon system. The valves are in the head and the cylinders are 2 7/8-inch bore by four-inch stroke. Piston displacement is 103 inches. This is only a little more than a third of the size set as the limit. The car has constant level circulating splash system of lubrication. There are two main crankshaft bearings and the crankshaft itself is of exception- ally large size.

The transmission is a sliding gear type, with two speeds forward and reverse. All transmission bearings are of the ball type. The clutch is a leather faced cone. Atwater-Kent ignition system and Holley carburetor are used. The axles are of the flexible type, that in the rear being similar in construction to the one used for many years on the French De Dion Bouton. Trans- verse semi-elliptic springs are used in front, and at the rear there is a platform of three transverse semi-elliptic springs.

Big Gasoline Mileage Possible.

The car is said to be able to run from 30 to 35 miles on a gallon of gasoline, and, as Chevrolet’s car has been equipped with an especially large gasoline tank, he expects to be able to run the race without stopping for gasoline or tires. The car was designed by Blood Brothers, Allegan, Mich., who will shortly begin to produce it commercially.

The three Duesenberg cars are not strangers in the big race. One of them took a place last year. They are the product of the Duesenberg Motor Company, St. Paul, a concern which specializes in motors for automobiles and motor boats. The engines have 3 63/64-inch bore and six-inch stroke, resulting in a piston displacement of 299 inches. The cylinders are cast en bloc and are very close coupled, so that a short motor is produced.

The crankcase is of the barrel type, and carries the motor lubricating oil. The crankshaft has only two main bearings. The front bearing is four inches long and the rear 42. The connecting rod bearings also are unusually large and are fitted with laminated shims, which make possible adjustments to 1/1000 of an inch. Pistons. are made of a light alloy steel and are so designed that they are effective in carrying away heat from the head of the cylinder through extensive light ribbing.

The cars are equipped with Rudge-Whitworth wire wheels and Riverside tires, 33 by 42 front and 33 by five rear. Timken bearings are used in all wheels, and New Departure bearings are installed installed in the transmission.

The Emden is a special car, built by three Donaldson brothers of Milford, Ia. The bore is 4½ inches and the stroke 54 inches, yielding a piston displacement of 298 inches. The weight of the car is 2200 pounds. Rudge-Whitworth wire wheels are equipped with 34 by 42 Goodrich Silvertown cord tires. Truffault-Hartford shock absorbers, Bosch double-distributor magneto and Rayfield carburetor are employed. A mineral oil, known as Oilzum, is used as a lubricant.

The Delage That Won Last Year.

John de Palma, brother of Ralph de Palma, succeeded in passing the elimination trials in the Delage car which, with Rene Thomas at the wheel, won the race last year. After qualifying he went for a spin on the track when it was wet and skidded through the new retaining wall at one of the curves. The strength of the impact tore the wall out for about 18 feet and the car turned over five or six times on the dirt. De Palma and his mechanician were not injured, and the damage to the car is not yet known. As there was a week left to get the car in shape for the race it is possible it may start.

Ball bearings are used in this Delage, and to secure rigidity, as well as lightness, an H section girder is carried under each main bearing. The motor is placed directly on the main frame members, while the five-speed gear box has three-point suspension. The clutch is a multiple disc. Two independent magnetos are fitted, and each cylinder has four horizontal valves, operated by vertical push rods and bell cranks. A gear pump, driven off the intake camshaft, delivers oil through a collector, in which are a hand regulated valve and three leads-one to the main bearings, one to the overhead valve gear and one to the dashboard pressure indicator. The function of the pump is limited to supplying lubricant to specially designed cages around each ball bearing.

In addition to the oil in the base chamber there is an auxiliary tank on the dash with a feed to the motor, the flow from which is regulated according to the conditions under which the motor is running. To prevent an excess, in case of inattention, or any other reason, there is an overflow on the side of the chamber, the superfluous oil being lost on the road.

Burman’s Car Special Peugeot.

Burman’s special car is an old Peugeot, in which he has installed a motor of his own design. This motor has 16 valves in the head, operated by an overhead camshaft. The cylinders have 3.6-inch bore by 7.1-inch stroke.

An attempt was made by Burman to enter this car as a Burman special, instead of as a Peugeot. Rival teams felt that if this were permitted the Peugeot would be represented by four cars, while they were held to the three permitted by the regulations. Ray Harroun, the Maxwell chief engineer and racing manager, therefore entered a special Maxwell under the name of Harroun special and announced that while the car was slightly different from the other Maxwells, it had been built in the Maxwell factories and after the race would be known as a Maxwell. This had the effect of having the Harroun special classed as a Maxwell and Burman’s car classed as a Peugeot, which was what Harroun had sought to accomplish.

The Bugatti, which Barney Oldfield was booked to drive, was built especially for racing. by Ettore Bugatti, an Italian, living in Molsheim, Alsace, Germany. Bugatti is said to have been responsible in a consulting capacity for much of the excellent design in French racing cars.

The car was built with a larger piston dis- placement than is permitted in the race. So it was taken to an American factory, where a crankshaft was designed that would permit a shorter piston throw, in an effort to bring it within the regulations. This alteration threw it out of tune and it did not work well in the elimination trials, although Oldfield managed to qualify with a speed of slightly more than 81 miles per hour. He later took a Sunbeam through the eliminations and it will not be known until the day of the race which car he will drive.

If Oldfield, or some other driver, takes the Bugatti into the race it will be the only car entered with chain drive. A dry plate disc clutch and a four-speed gearset are used. The car weighs about 1800 pounds.

The F. R. P. cars, which could not be put in shape in time for the race, contained some very interesting new Knight engine designs. They may be perfected for some of the later speedway races. The valve sleeves are operated by two eccentrics instead of one. An auxiliary exhaust port has been installed close to the lower end of the valve sleeve. The port areas are larger than usual and the sleeve stroke shorter.

With these changes it is said to be possible to run these motors as fast as 5000 revolutions per minute. Horsepower curves show that they develop 122 horsepower at 3950 revolutions per minute. They weigh 1910 pounds.

Mulford failed to get the special car which he had been building at his Brooklyn shops ready in time, and so he qualified in a Duesenberg. His own car had 3 11/16-inch bore by seven-inch stroke. It has an offset crankshaft, and two cam- shafts with only three timing gears. Two in- dependent oiling systems and two independent ignition systems were installed.

New Stutz Has 16 Valves.

Some details of design in the Stutz racing cars will be kept secret until after the race. They are not stock cars, however, being the first strictly racing types produced at the Stutz factory. Their four-cylinder motors, cast en bloc, are 3 3/16 inches by 6.5 inches. They have 103-inch wheelbase. They use Houck wire wheels and Goodrich Silvertown cord tires.

The motors have 16 overhead valves, operated by an overhead camshaft. The valves enter the cylinder at an angle between horizontal and vertical. The crankshaft is carried on three main bearings of the ball type. The motor is oiled by a combination force feed system, which delivers oil independently to the ball bearings of the crankshaft and through the hollow shaft itself to the lower connecting rod bearings. The pistons are very light, and the motor reaches its greatest efficiency at about 2800 revolutions per minute. The weight of the car is 2150 pounds. The rear system is similar in all details to that employed on stock Stutz cars.

Ralph de Palma’s Mercedes, which once won a Grand Prix in France, and has taken two of the fast Elgin road races, is in the best of trim. He made the fastest time of any car in the elimination trials and was only a small fraction under the record for the track. The car has been completely overhauled at the Packard factory and fitted with a streamline body of new design, which is said to reduce wind resistance to the minimum. It has been fitted also with a Packard carburetor. The motor is 35% by six inches, and the car weighs about 2300 pounds. Wheelbase is 110 inches.

The Cino-Purcell is a Cincinnati car that has been very successful in the past in competing in hill climbs, but has not previously been entered in the big race. It is heavier than most of the other cars, tipping the scales at 2450 pounds. The Kleinart is a special car designed and built by Arthur Klein, its driver. The Mais is a car about which information is scarce and the same is true of the Sebring, which J. Cooper will drive.

Fifteen of the cars are equipped with Bosch magnetos, including the Maxwell, Stutz, Peugeot, Sunbeam, Mercedes, Duesenberg and Mais entries. Master carburetors are used on three Maxwells, one Sunbeam, one Peugeot and two Duesenbergs. Two of the Stutz cars have Stromberg carburetors. One Peugeot and one Stutz are fitted with Zeniths. Schebler carburetors are used on one Duesenberg and a Sebring. The Mais uses a Rayfield and the Cornelian a Claudel, while Ralph de Palma’s Mercedes is fitted with a Packard carburetor. These figures are not complete and there are doubtless other cars fitted with some of these carburetors and magnetos.

Many Great American Drivers.

An exceptionally complete list of the great American drivers will compete in this year’s race. Many of the men who have been driving racing cars since racing first became an established sport are among the entrants. Bob Burman, and his old team mate of the days when the Buick was a great leader of the racing game, Louis Chevrolet, will both appear in the race. Burman has made racing his steady occupation since he began with a Jackson car at Detroit in 1906. Lately he has been a prominent member of the Peugeot team, but until he took first place in the Oklahoma City races, the last big event before the Indianapolis contest, he had not been especially successful of late.

Chevrolet has been a manufacturer during the past few years, devoting himself to the production of the Chevrolet car. Lured by his memory of the excitement of his racing days, and much attracted by some of the features of design in the sensational little Cornelian, he offered himself as the pilot of that car. He weighs 200 pounds and his car less than 1000. It is unnecessary to say that the combination is one of the most interesting to be seen at the track.

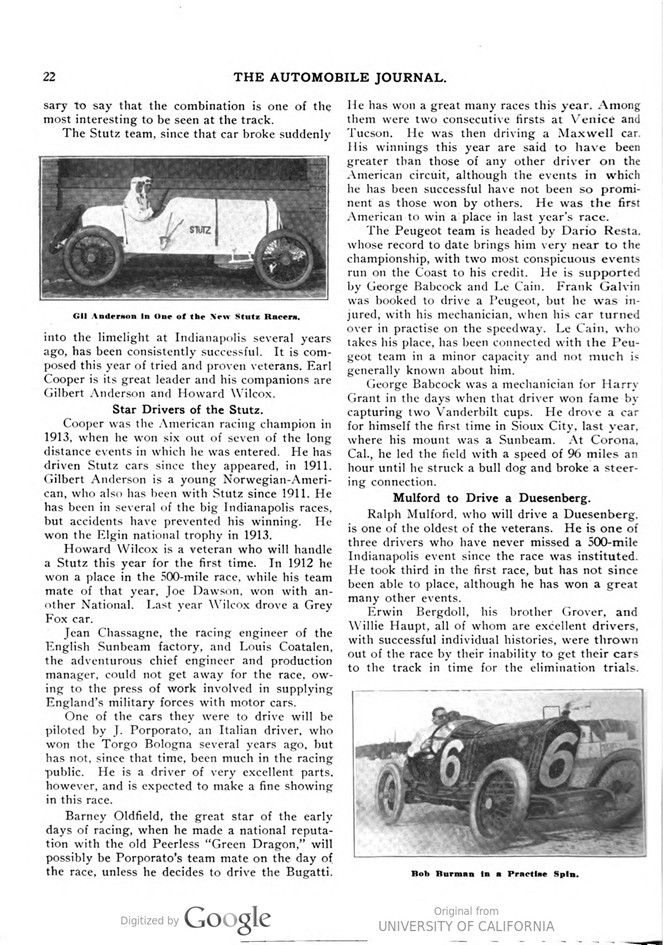

The Stutz team, since that car broke suddenly into the limelight at Indianapolis several years ago, has been consistently successful. It is composed this year of tried and proven veterans. Earl Cooper is its great leader and his companions are Gilbert Anderson and Howard Wilcox.

Star Drivers of the Stutz.

Cooper was the American racing champion in 1913, when he won six out of seven of the long distance events in which he was entered. He has driven Stutz cars since they appeared, in 1911. Gilbert Anderson is a young Norwegian-American, who also has been with Stutz since 1911. He has been in several of the big Indianapolis races, but accidents have prevented his winning. He won the Elgin national trophy in 1913.

Howard Wilcox is a veteran who will handle a Stutz this year for the first time. In 1912 he won a place in the 500-mile race, while his team mate of that year, Joe Dawson, won with another National. Last year Wilcox drove a Grey Fox car.

Jean Chassagne, the racing engineer of the English Sunbeam factory, and Louis Coatalen, the adventurous chief engineer and production manager, could not get away for the race, owing to the press of work involved in supplying England’s military forces with motor cars.

One of the cars they were to drive will be piloted by J. Porporato, an Italian driver, who won the Torgo Bologna several years ago, but has not, since that time, been much in the racing public. He is a driver of very excellent parts, however, and is expected to make a fine showing in this race.

Barney Oldfield, the great star of the early days of racing, when he made a national reputation with the old Peerless „Green Dragon,“ will possibly be Porporato’s team mate on the day of the race, unless he decides to drive the Bugatti. He has won a great many races this year. Among them were two consecutive firsts at Venice and Tucson. He was then driving a Maxwell car. His winnings this year are said to have been greater than those of any other driver on the American circuit, although the events in which he has been successful have not been so prominent as those won by others. He was the first American to win a place in last year’s race.

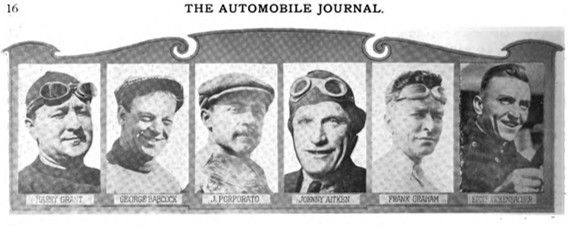

The Peugeot team is headed by Dario Resta, whose record to date brings him very near to the championship, with two most conspicuous events run on the Coast to his credit. He is supported by George Babcock and Le Cain. Frank Galvin was booked to drive a Peugeot, but he was injured, with his mechanician, when his car turned over in practise on the speedway. Le Cain, who takes his place, has been connected with the Peugeot team in a minor capacity and not much is generally known about him.

George Babcock was a mechanician for Harry Grant in the days when that driver won fame by capturing two Vanderbilt cups. He drove a car for himself the first time in Sioux City, last year, where his mount was a Sunbeam. At Corona, Cal., he led the field with a speed of 96 miles an hour until he struck a bull dog and broke a steering connection.

Mulford to Drive a Duesenberg.

Ralph Mulford, who will drive a Duesenberg. is one of the oldest of the veterans. He is one of three drivers who have never missed a 500-mile Indianapolis event since the race was instituted. He took third in the first race, but has not since been able to place, although he has won a great many other events.

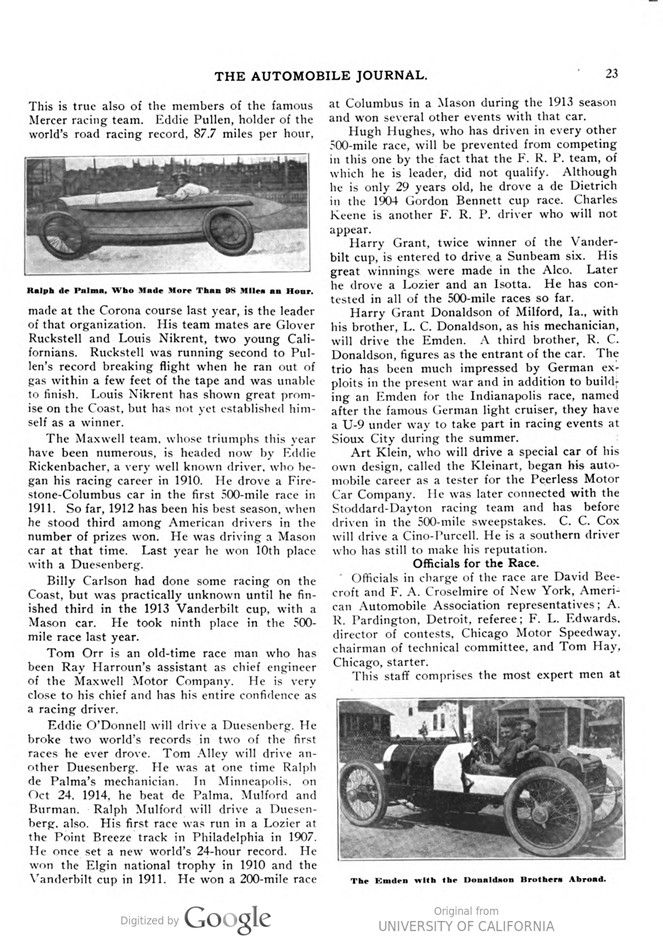

Erwin Bergdoll, his brother Grover, and Willie Haupt, all of whom are excellent drivers, with successful individual histories, were thrown out of the race by their inability to get their cars to the track in time for the elimination trials. This is true also of the members of the famous Mercer racing team. Eddie Pullen, holder of the world’s road racing record, 87.7 miles per hour, made at the Corona course last year, is the leader of that organization. His team mates are Glover Ruckstell and Louis Nikrent, two young Cali- fornians. Ruckstell was running second to Pullen’s record breaking flight when he ran out of gas within a few feet of the tape and was unable to finish. Louis Nikrent has shown great promise on the Coast, but has not yet established himself as a winner.

The Maxwell team, whose triumphs this year have been numerous, is headed now by Eddie Rickenbacher, a very well known driver, who began his racing career in 1910. He drove a Firestone-Columbus car in the first 500-mile race in 1911. So far, 1912 has been his best season, when he stood third among American drivers in the number of prizes won. He was driving a Mason car at that time. Last year he won 10th place with a Duesenberg.

Billy Carlson had done some racing on the Coast, but was practically unknown until he finished third in the 1913 Vanderbilt cup, with a Mason car. He took ninth place in the 500-mile race last year.

Tom Orr is an old-time race man who has been Ray Harroun’s assistant as chief engineer of the Maxwell Motor Company. He is very close to his chief and has his entire confidence as a racing driver.

Eddie O’Donnell will drive a Duesenberg. He broke two world’s records in two of the first races he ever drove. Tom Alley will drive another Duesenberg. He was at one time Ralph de Palma’s mechanician. In Minneapolis, on Oct 24, 1914, he beat de Palma, Mulford and Burman. Ralph Mulford will drive a Duesenberg. also. His first race was run in a Lozier at the Point Breeze track in Philadelphia in 1907. He once set a new world’s 24-hour record. won the Elgin national trophy in 1910 and the Vanderbilt cup in 1911. He won a 200-mile race at Columbus in a Mason during the 1913 season and won several other events with that car.

Hugh Hughes, who has driven in every other 500-mile race, will be prevented from competing in this one by the fact that the F. R. P. team, of which he is leader, did not qualify. Although he is only 29 years old, he drove a de Dietrich in the 1904 Gordon Bennett cup race. Charles Keene is another F. R. P. driver who will not appear.

Harry Grant, twice winner of the Vanderbilt cup, is entered to drive a Sunbeam six. His great winnings were made in the Alco. Later he drove a Lozier and an Isotta. He has contested in all of the 500-mile races so far.

Harry Grant Donaldson of Milford, Ia., with his brother, L. C. Donaldson, as his mechanician, will drive the Emden. A third brother, R. C. Donaldson, figures as the entrant of the car. The trio has been much impressed by German exploits in the present war and in addition to building an Emden for the Indianapolis race, named after the famous German light cruiser, they have a U-9 under way to take part in racing events at Sioux City during the summer.

Art Klein, who will drive a special car of his own design, called the Kleinart, began his automobile career as a tester for the Peerless Motor Car Company. He was later connected with the Stoddard-Dayton racing team and has before driven in the 500-mile sweepstakes. C. C. Cox will drive a Cino-Purcell. He is a southern driver who has still to make his reputation.

Officials for the Race.

Officials in charge of the race are David Beecroft and F. A. Croselmire of New York, American Automobile Association representatives; A. R. Pardington, Detroit, referee; F. L. Edwards, director of contests, Chicago Motor Speedway, chairman of technical committee, and Tom Hay, Chicago, starter.

This staff comprises the most expert men at their various branches of the work. Beecroft, Pardington and Edwards have officiated at every speedway race since they began to be held at the Indianapolis. Hay and Croselmire have each had one year’s experience. Hay is an old bicycle team mate of Carl G. Fisher, president of the Indianapolis Speedway Company.

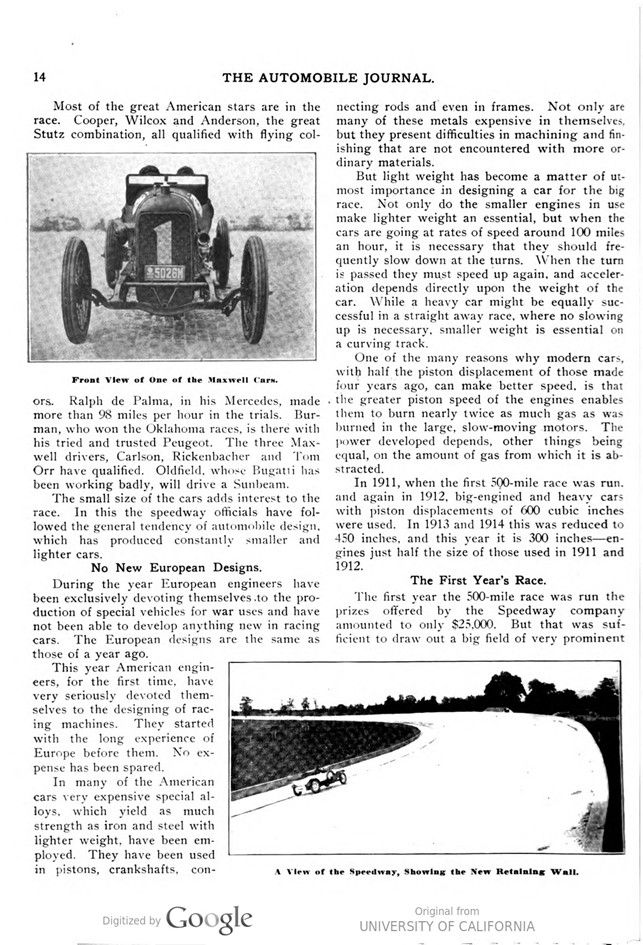

During the year an improvement has been made in the speedway construction, which is expected to prevent many serious accidents. It was given a trial by an accident that occurred during practise recently and saved a driver from serious. injury and perhaps the wrecking of his car.

This is a safety wall all the way, around the course. George Babcock, one of the Peugeot team, had a blow-out during a fast trip over the track and slid over onto what would have been a soft strip of earth if the retaining wall had not been there to stop him. Instead of digging the front end of his car into the earth and turning a somersault, as many racing drivers have done before him, Babcock simply struck the concrete wall, slid along and finally came to a stop. The wall was built at a considerable expense to prevent just such accidents.

The wall gave way when John de Palma’s Delage struck it, but it saved the driver and mechanician from serious injury.

Foto captions.

Page 14. Front View of One of the Maxwell Cars – A View of the Speedway, Showing the New Retaining Wall.

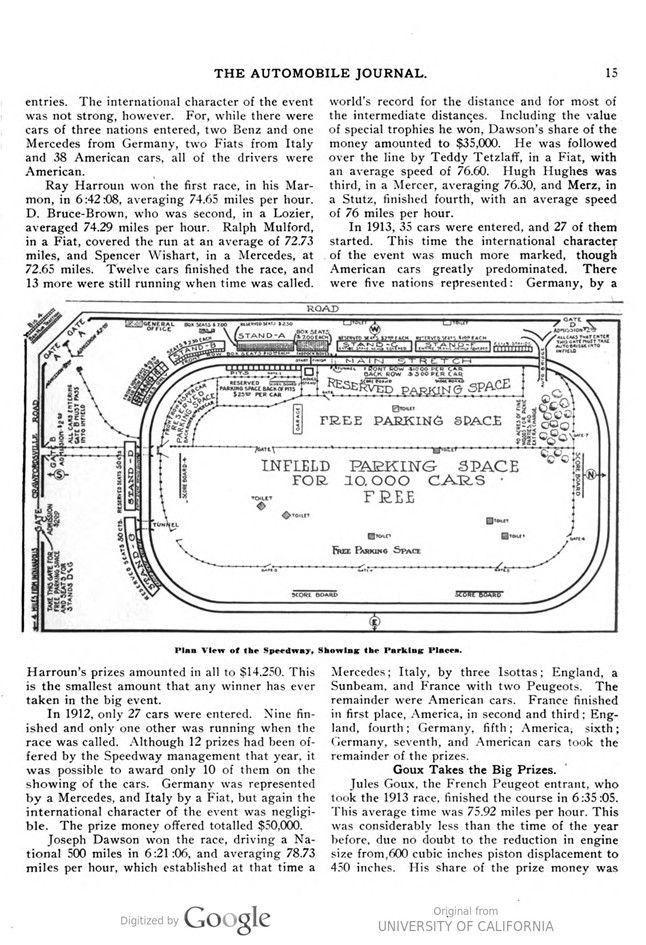

Page 15. Plan View of the Speedway, Showing the Parking Places.

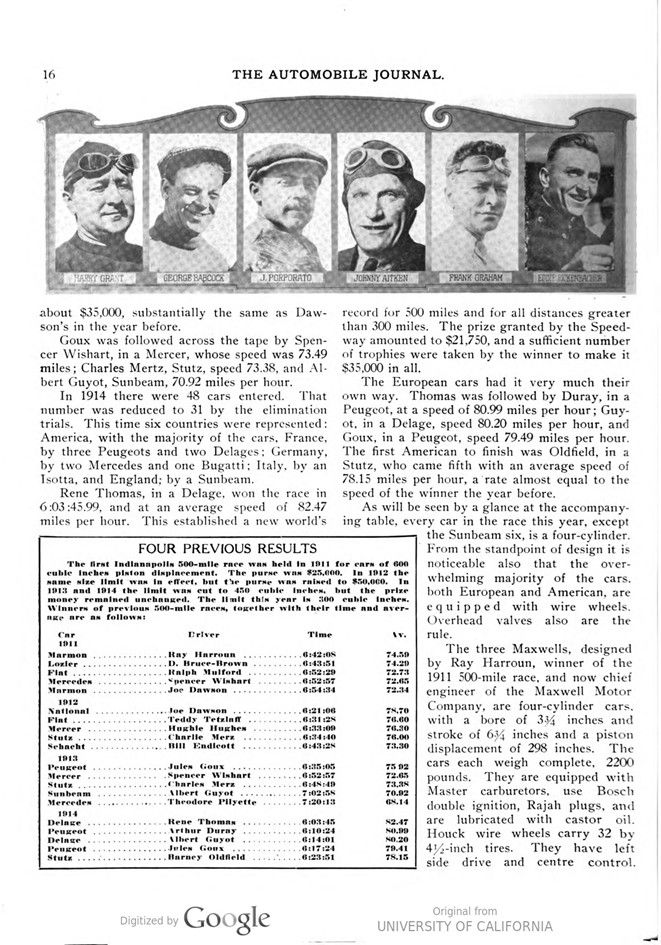

Page 16. HARRY GRANT – GEORGE BABCOCK – J. PORPORATO – JOHNNY AITKEN – FRANK GRAHAM – EDDIE RICKENBACHER

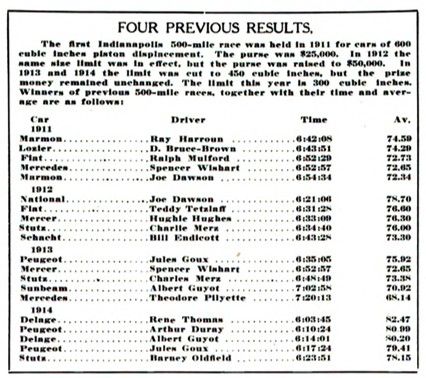

FOUR PREVIOUS RESULTS – The first Indianapolis 500-mile race was held in 1911 for cars of 600 cubic inches piston displacement. The purse was $25,000. In 1912 the same size limit was in effect, but the purse was raised to $50,000. 1913 and 1914 the limit was cut to 450 cubie inches, but the prize money remained unchanged. The limit this year is 300 cubic inches. Winners of previous 500-mile races, together with their time and aver- age are as follows: Car, Diver, Time, Av. (see table).

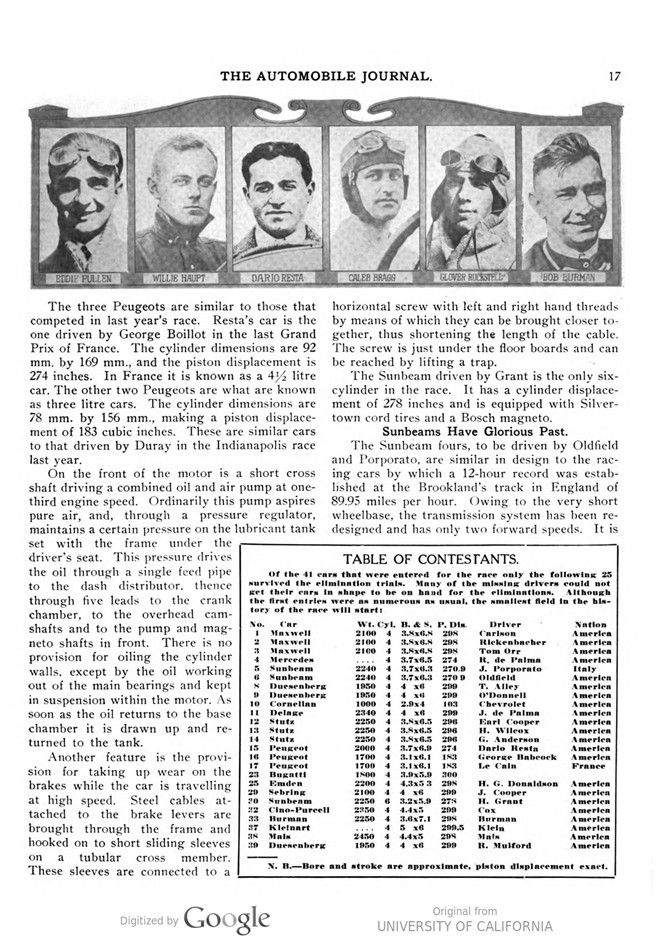

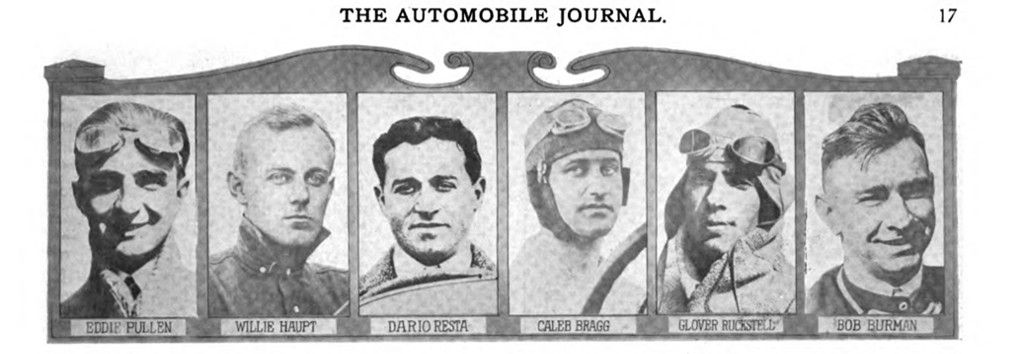

Page 17. EDDIE PULLEN – WILLIE HAUPT – DARIO RESTA – CALEB BRAGG – GLOVER RUCKSTELL – BOB BURMAN

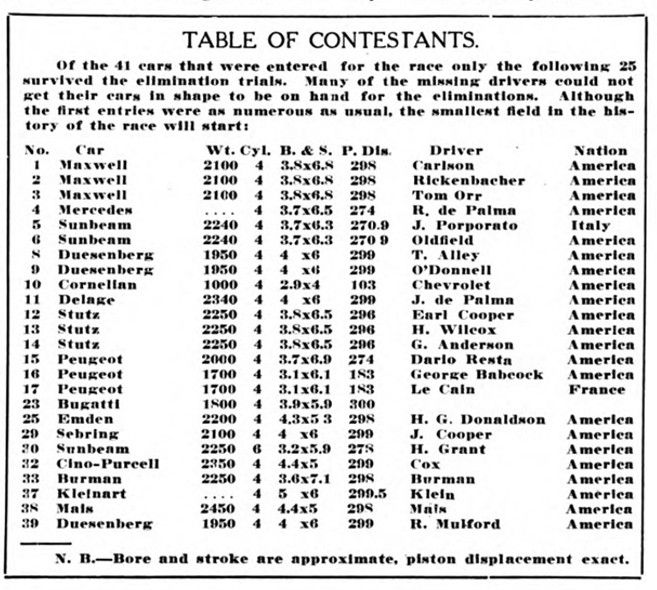

TABLE OF CONTESTANTS. Of the 41 cars that were entered for the race only the following 25 survived the elimination trials. Many of the missing drivers could not get their cars in shape to be on hand for the eliminations. Although the first entries were as numerous as usual, the smallest field in the his- tory of the race will start: (see table).

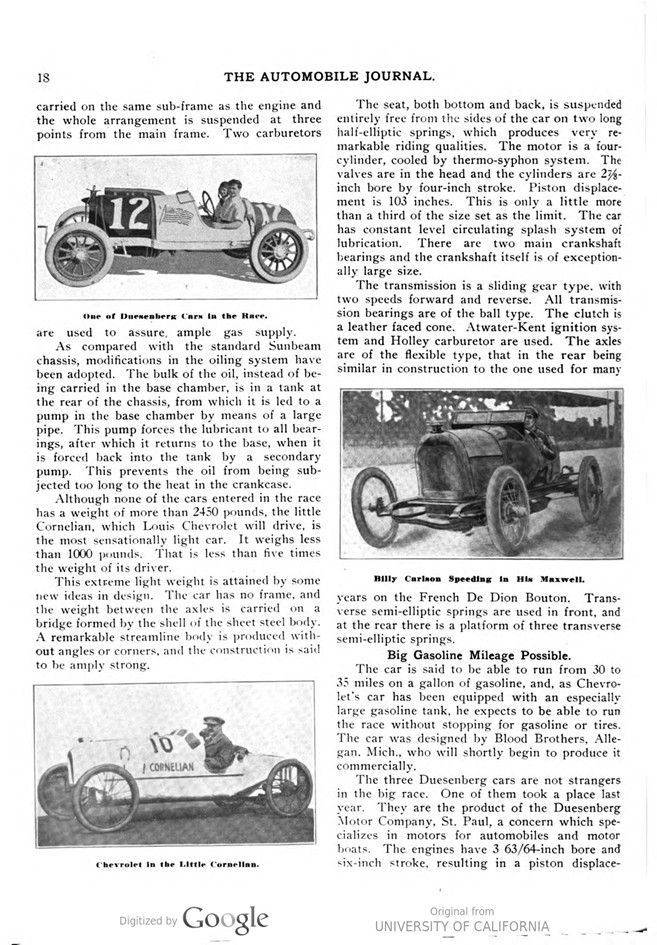

Page 18. One of Duesenberg Cars in the Race. – Chevrolet in the Little Cornelian. -Billy Carlson Speeding in His Maxwell.

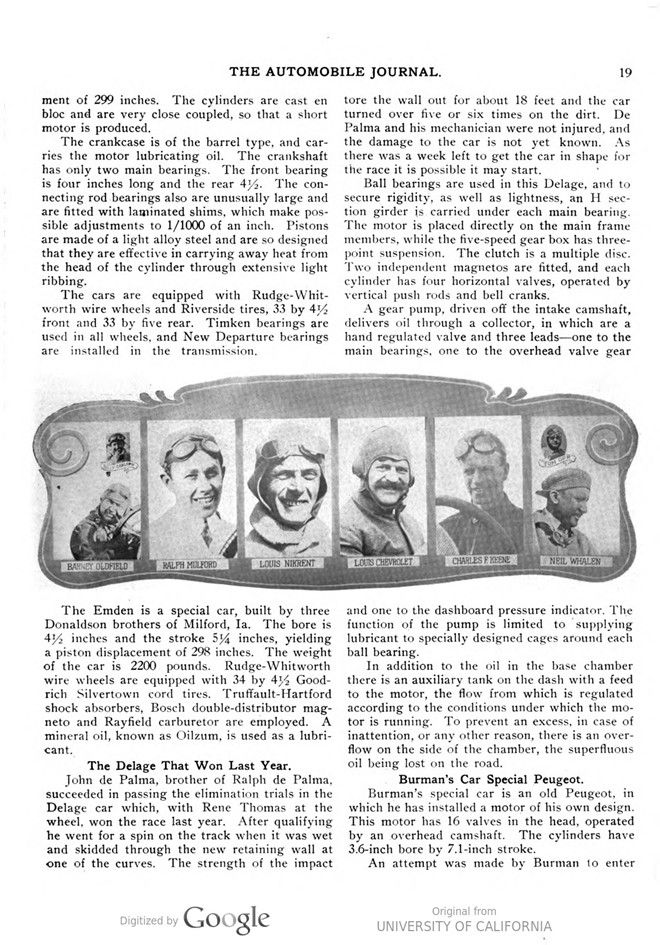

Page 19. BARNEY OLDFIELD – RALPH MULFORD – LOUIS NIKRENT – LOUIS CHEVROLET – CHARLES F KEENE – NEIL WHALEN

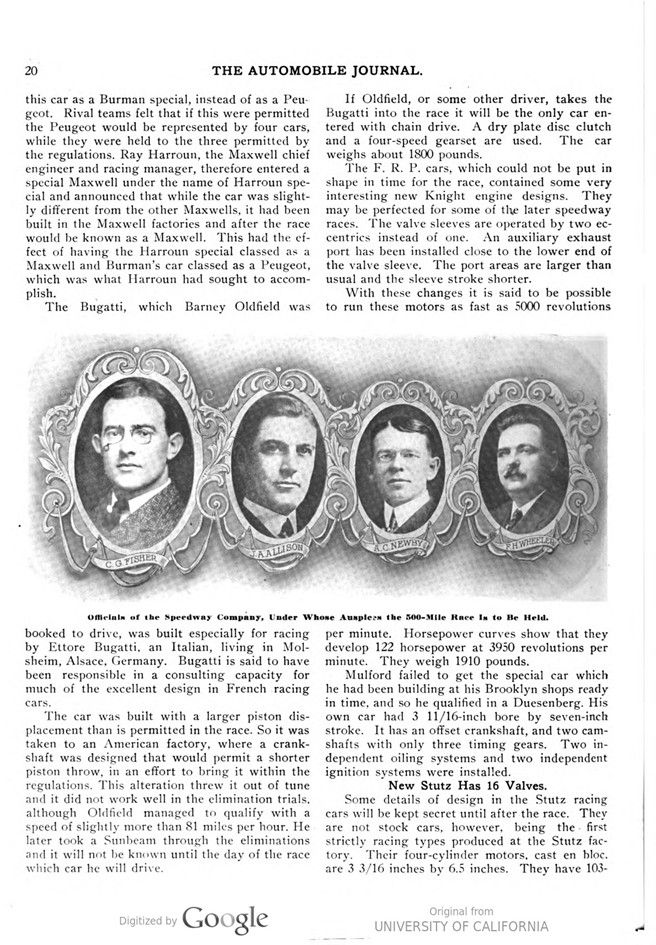

Page 20. C.G. FISHER – A. ALLISON – A.C. NEWBY – F.H. WHEELER.

Officials of the Speedway Company, Under Whose Auspices the 500-Mile Race Is to Be Held.

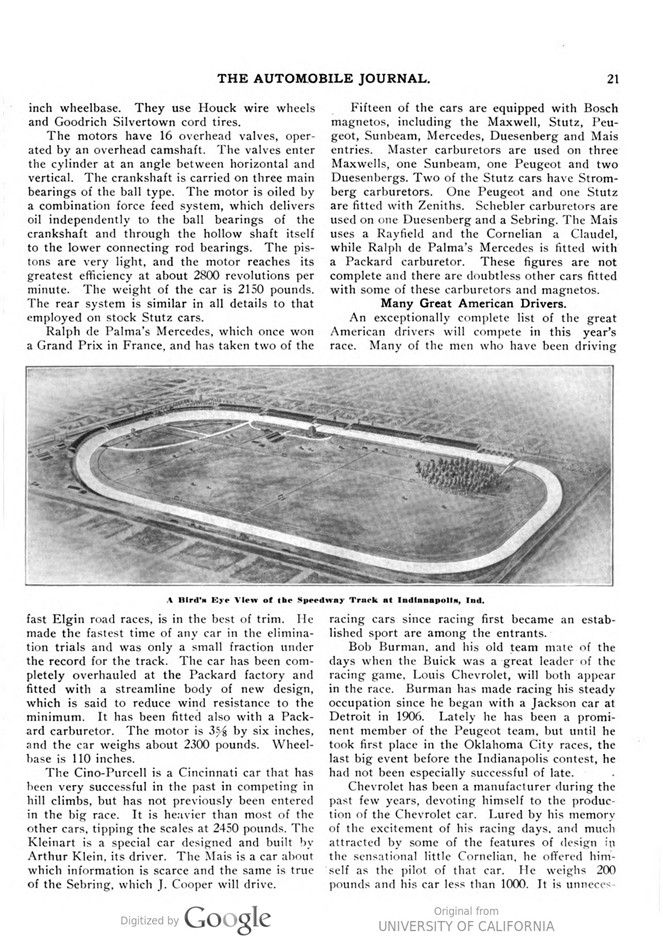

Page 21. A Bird’s Eye View of the Speedway Track at Indianapolis, Ind.

Page 22. STUTZ Gil Anderson in One of the New Stutz Racers. – Bob Burman in a Practise Spin.

Page 23. Ralph de Palma, Who Made More Than 98 Miles an Hour. – The Emden with the Donaldson Brothers Abroad.