Text and pictures with courtesy of Hathitrust.org; compiled by motorracinghistory

MOTOR, Supplement A,B,C,D – October 1905 – Page 24-26

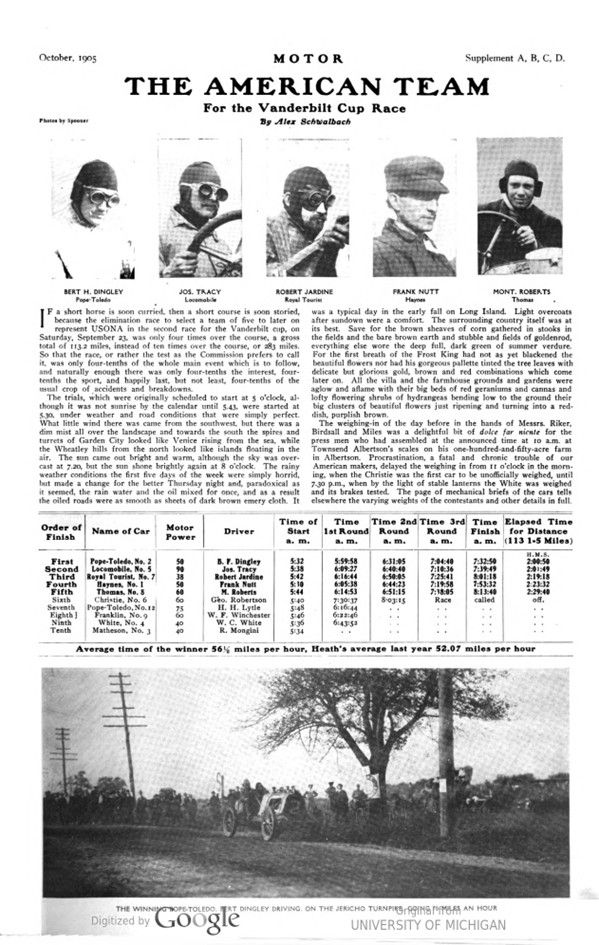

THE AMERICAN TEAM

For the Vanderbilt Cup Race

By Alex Schwalbach (Photos by Spooner)

IF a short horse is soon curried, then a short course is soon storied, because the elimination race to select a team of five to later on represent USONA in the second race for the Vanderbilt cup, on Saturday, September 23, was only four times over the course, a gross total of 113.2 miles, instead of ten times over the course, or 283 miles. So that the race, or rather the test as the Commission prefers to call it, was only four-tenths of the whole main event, which is to follow, and naturally enough there was only four-tenths the interest, four-tenths the sport, and happily last, but not least, four-tenths of the usual crop of accidents and breakdowns.

The trials, which were originally scheduled to start at 5 o’clock, although it was not sunrise by the calendar until 5.43, were started at 5.30, under weather and road conditions that were simply perfect. What little wind there was, came from the southwest, but there was a dim mist all over the landscape and towards the south the spires and turrets of Garden City looked like Venice rising from the sea, while the Wheatley hills from the north looked like islands floating in the air. The sun came out bright and warm, although the sky was overcast at 7.20, but the sun shone brightly again at 8 o’clock. The rainy weather conditions the first five days of the week were simply horrid but made a change for the better Thursday night and, paradoxical as it seemed, the rainwater and the oil mixed for once, and as a result the oiled roads were as smooth as sheets of dark brown emery cloth. It was a typical day in the early fall on Long Island. Light overcoats after sundown were a comfort. The surrounding country itself was at its best. Save for the brown sheaves of corn gathered in stooks in the fields and the bare brown earth and stubble and fields of goldenrod, everything else wore the deep full, dark green of summer verdure. For the first breath of the Frost King had not as yet blackened the beautiful flowers nor had his gorgeous palette tinted the tree leaves with delicate but glorious gold, brown and red combinations which come later on. All the villa and the farmhouse grounds and gardens were aglow and aflame with their big beds of red geraniums and cannas and lofty flowering shrubs of hydrangeas bending low to the ground their big clusters of beautiful flowers just ripening and turning into a reddish, purplish brown.

The weighing-in of the day before in the hands of Messrs. Riker, Birdsall and Miles was a delightful bit of dolce far niente for the press men who had assembled at the announced time at 10 a.m. at Townsend Albertson’s scales on his one-hundred-and-fifty-acre farm in Albertson. Procrastination, a fatal and chronic trouble of our American makers, delayed the weighing in from 11 o’clock in the morning, when the Christie was the first car to be unofficially weighed, until 7.30 p.m., when by the light of stable lanterns, the White was weighed and its brakes tested. The page of mechanical briefs of the cars tells elsewhere the varying weights of the contestants and other details in full.

New Yorkers have the modern habit of turning night into day, and the night before the race was no exception. Mineola might then be well named Bedlam, and if you throw in teuf-teufs, Jericho and Gabriel’s horns ad lib. you have the whole story. The Long Island Automobile Club camped out in tents with blazing log campfires at the starting point; all their guests met with a cheerful reception both inwardly and outwardly, their liquid demonstration being overwhelming, and every departing visitor was handed a large, white paper box inscribed „Midnight Lunch.” It contained dainty sandwiches, cake, cream cheese and crisp crackers, raw tomatoes, pepper and salt, and for dessert sponge cake and Bartlett pears, all neatly done up in waxed papers and Japanese napkins.

MOTOR’s good and original suggestion to place the starting and finishing points at Mineola was adopted, and as a consequence over five thousand spectators gathered at that point to view the race, over six hundred cars being parked there alongside the course. The view of the course from the double-decked press box and grandstand both ways was magnificent. The contestants, as they appeared in sight from New Hyde Park, dashed down and up the rolling grades of the homestretch like huge swallows skimming the earth, and after they passed the grandstand through the narrow, crowded aisles of people the same performance was repeated in the reverse direction.

The announcer’s details of the race from the various telephone points on the course came so rapidly as to be almost a continuous performance. The start itself was not an exciting one. None of the cars got away to what might be called a good start. In fact, the Christie had to be almost pushed over the tape, owing to inability to crank it off. Lytle had his brake jammed on, and White, in his eagerness to get the pressure of his head of steam, threw open his throttle so wide as to break his toggle joint.

There was a great lack of applause for the cars and drivers at the start, even the press men who led the applause last year being too much occupied with their data to give the drivers the glad hand, but there was more general interest taken in the race throughout, lap by lap, and in the records of the announcers, which shows that we have learned to appreciate road racing, but it might also be possible that the small crowd warmed up better this year because the day itself was warmer than last year.

The warning signals were most excellent. The markers on the course who were always in sight of one another displayed warning flags of red and yellow, reversing the rule, however; for while a red flag meant danger to the public, it meant to the drivers of the cars that the road was clear, and the yellow flag, which meant safety to the public, meant danger to the drivers; besides that all the drivers had printed cards with these facts on their dashboards in front of them, so that they would not get these inverted signals mixed up.

The huge grandstand presented a beggarly array of empty benches, as was anticipated by those in the know, but which will not be so on October 14. Society was not very well represented, and what little there was, was not clad sartorially perfect. It would seem as if the small female portion of society present had used the occasion to dis- play their old duds and appear in gay colors at a daybreak function, when street and walking costumes should have been in order.

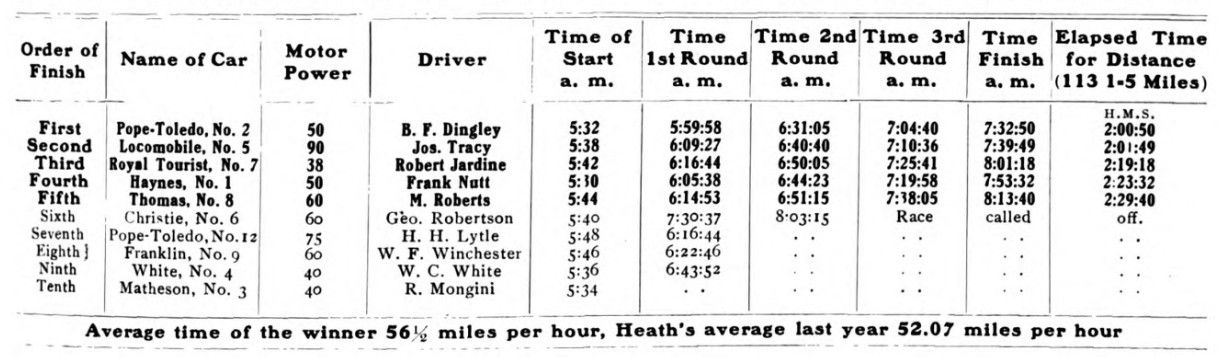

The management of the race was most excellent and the same may be said of the timing with one exception. Dingley’s time for the first lap was announced as being 25 minutes and 58 seconds. A dozen good watches and expert timers in the press box and hundreds at the finish made this time as 27 minutes and 58 seconds. An objection was at once made to the officials, but without avail. The press men decided that they would announce their own time as being correct, but not officially, denouncing the announced time as being a gross and palpable error. The self-constituted authorities on timing, the Chronograph Club of Boston and the Timing Club of New York, should bear in mind that timing, like Cæsar’s wife, should be above suspicion. After the race was over the timers decided in some way that their first announcement, after all, was wrong, and gave out the correct time as announced by the press men. In last year’s race some trouble occurred at the beginning between the press men and the timers about the method of timing and the method of announcing, hence it does seem before the big race itself occurs that the official timers should hie themselves to a bicycle road race and witness the timing and placing of 150 starters who come over the finishing tape in bunches of six, eight and ten, all of which are correctly timed and placed. It seems incredible that anybody of men could make an error of two minutes in announcing the official time of a race. Variations of from one to three-fifths of a second between individual timers might be expected, but the majority of timers should and must agree upon someone time to make the thing accurate and of value.

The race itself was remarkable for three things. Firstly, because of the fact that few tire troubles occurred, Christie being the only man who had tire troubles – and his were undoubtedly caused by using tires that were not pumped up hard enough. In fact, he was looking around for a pump before the start. Secondly, because punctures were unknown, whereas in last year’s race over a course that was undoubtedly salted with nails and glass, punctures were frequent, but thirdly and lastly, after all the great feature of the race was the triumph of the three touring cars and the regularity of their times over the course, although the big Locomobile racer shared in this regularity, but then it must be conceded that the Locomobile racer is not a freak, it being a heroic reproduction of the touring car.

The winning Pope-Toledo is classed by its makers as having fifty motor-power, and therefore comes within the scope of a touring car. It is true that the course this year is faster than last year’s, because it is without controls. A control means a slowing up and a stopping to get into the control, and it means a slow start to get out of the control, besides a loss of time before headway is again acquired. A reference to the timetable of laps will show just how regular the cars ran over the course, three of them showing an actual improvement, instead of falling off, as the trial neared the end: 1st. 2nd. 3rd. 4th.

Pope-Toledo 27:58 31:07 33:35 28:10

Locomobile 31:27 31:13 29:56 29:13

Royal Tourist 34:44 33:21 35:36 35:37

Haynes 35:38 38:45 35:35 33:34

Thomas 30:53 36:22 36:50 45:35

The race was officially declared off at 8:14, although at that time Christie was still running on the course and the first five had finished, the others being out of it. Jardine’s upset in the woods on the Guinea road was a lucky one indeed and might have cost him his car’s place on the team. It demonstrates, however, just what a touring car can stand as opposed to a frail contraption such as racing freaks are.

A rose by any other name would smell as sweet; abroad the Richard-Brasier scoops in everything, and possibly the fact that the Pope-Toledo is a car with a hyphenated cognomen may account for part of its victory in the test. The test itself was originally hoodooed by thirteen entries, but that was broken when only ten cars started.

The two most dramatic features of the trial, after all, was the way in which Lytle, on the Pope-Toledo, passed Jardine in front of the grandstand on the first lap, and the anxiety on the last lap after Dingley had finished first, to know whether Tracy, who led him four seconds on the third round, but who started six minutes later, would beat him out on time. Slowly the six minutes were counted off, and it became apparent then, just as Tracy hove in sight from New Hyde Park, that, of course, he could not beat Dingley out, the interest then centering to know how much Dingley had beaten him, which was exactly 59 seconds.

Dingley led in the first round, followed by Tracy, Roberts, Jardine and Nutt. In the second round Dingley led again, the others in the same order; in the third round, however, Tracy was first and Dingley second, the others still in the same order. In the fourth and last round Dingley led, Tracy second, Jardine third, Nutt fourth and Roberts fifth. Tracy and Nutt did the four laps without stopping. Dingley stopped for a moment or two on the third round with some ignition and carbureter trouble. Roberts dropped pieces of the hard rubber off his battery in front of the grandstand, indicating ignition trouble.

In the list of the „also rans“ the Christie, which finished two rounds, was out because of tire troubles; Lytle, on the big Pope-Toledo, broke the cross member off his frame which carried the engine, and White, on the steamer, broke two joints in his universal shaft, besides having water trouble. The big, air-cooled Franklin, of Winchester, cast a bolt out of the universal joining the gasoline tank and caused it to leak; while the Matheson had some lubricating trouble which caused the piston to stick in the cylinder.

Dingley averaged 56.50 miles per hour; Tracy, 55.75; Jardine, 48.76; Nutt, 46.24; Roberts, 45:50. Dingley averaged per mile, 1 minute 4.05 seconds; Tracy, 1, 4.57; Jardine 1, 13.83; Nutt, 1, 16.08; Roberts, 1, 19.33; while both Dingley and Tracy beat Heath’s average speed per hour of last year, which was only 52.07.

Photo captions.

Page 24.

BERT H. DINGLEY Pope-Toledo / JOS. TRACY Locomobile / ROBERT JARDINE Royal Tourist / FRANK NUTT Haynes / MONT. ROBERTS Thomas

THE WINNING POPE-TOLEDO. BERT DINGLEY DRIVING. ON THE JERICHO TURNPIKE. GOING 70 MILES AN HOUR

Page 25.

Page KEY TO ILLUSTRATIONS

A – Jericho Turnpike, Looking from the Press Stand toward Mineola Crossing.

B and C – Royal Tourist Motor, Inlet and Exhaust Sides.

D and E – Thomas Motor, Inlet and Exhaust Sides. F – The Royal Tourist Nearing the Finish on the Last Round. G – The Six-cylinder Thomas Going at Top Speed on the Jericho Turnpike. H – The Six-cylinder Pope-Toledo, Lytle Driving, Just Before the Mishap. I – The Christie, Which Lost a Place Through Tire Trouble. J – The Locomobile (No. 5) and the White Ready to Start. K – The Haynes Car, which Won Fourth Place. L and M – Pope-Toledo, Inlet and Exhaust Sides. N and O – Haynes Motor, Exhaust and Inlet Sides. P – Motor Locomobile at Guinea Woods Turn.