Text and pictures with courtesy of Hathitrust.org; compiled by motorracinghistory

The Motor World. – Vol. XI, No. 1, September 28, 1905.

The Tale of the First Eliminating Trial

How the Race was Run and Won that Did Not Decide the Make-up of the American Team

Stock Cars Make a Superb Showing – Two Big Favorites Bowled Out Early.

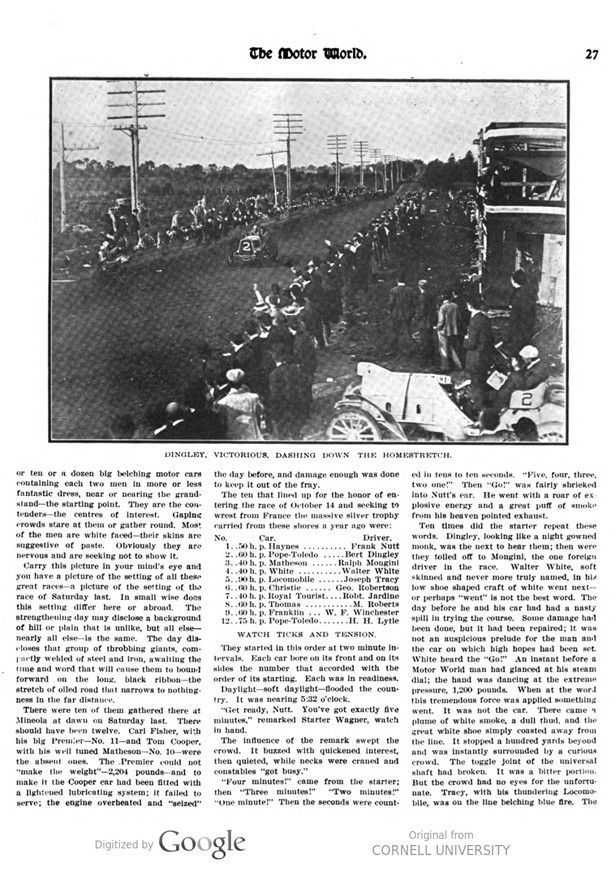

Quite unexpectedly, two trials were necessary to decide the make-up of the team that shall represent America in the race for the Vanderbilt Cup on October 14.

As per programme, the first trial occurred on the Long Island course on Saturday morning last, 23d inst. The second trial took place on Monday night, 25th inst., in the rooms of the Automobile Club of America, in New York City. W. K. Vanderbilt, Jr.. the donor of the cup, was referee of the road trial. He also was present at the meeting of the Vanderbilt Cup commission, which sat in judgment and rendered the verdict in the second trial-a verdict that unloosed hell of contention and denunciation.

In Monday’s trial on the road these men and these cars qualified: 1, Bert F. Ding- ley, 60 horsepower Pope-Toledo; 2, Joseph Tracy, 90 horsepower Locomobile; 3, Robert Jardine, 40 horsepower Royal; 4, Frank Nutt, 50 horsepower Haynes; 5, Mortimer Roberts, 60 horsepower Thomas.

In the clubroom trial on Monday the qualification of Dingley and Tracy passed unchallenged, but for Jardine, Nutt and Roberts there were substituted H. H. Lytle, 75 horsepower Pope-Toledo; Walter C. White, 40 horsepower White, and Walter Christie, 120 horsepower Christie, each of whom in the road trial suffered an accident that prevented him from completing the full distance of 113.2 miles, made up of four circuits of 28.3 miles. Despite the storm that is blowing there is small reason to believe that the result of the second trial will be altered.

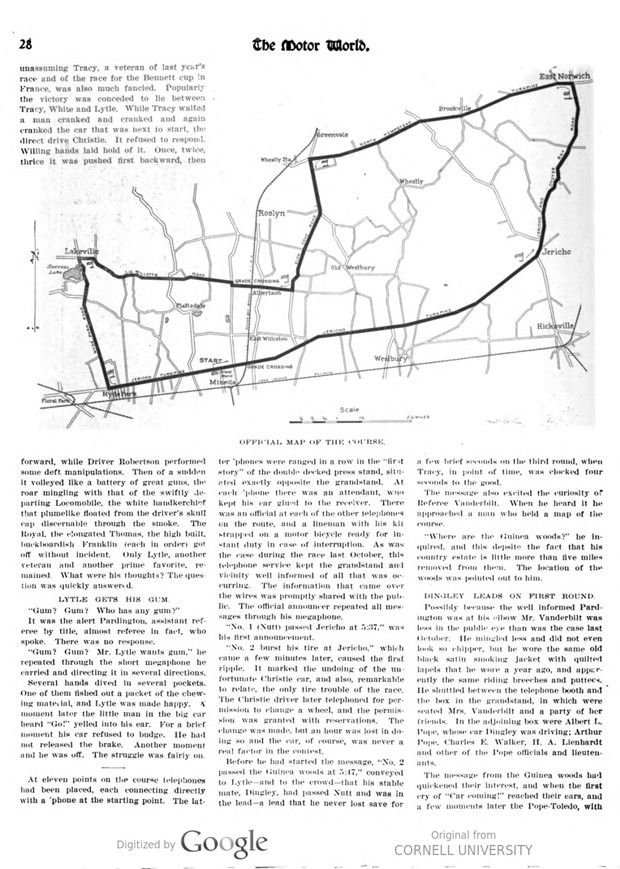

This story has to do only with the first trial – the race over the pipe shaped course laid out in the most picturesque, rolling portion of Nassau County, N. Y., a portion in which houses are few and far between, and in which for the amount of travel to which they are subjected, much of the road is ununderstandably good. Perhaps it is due to the fact that Wealth has not a few estates in the vicinity.

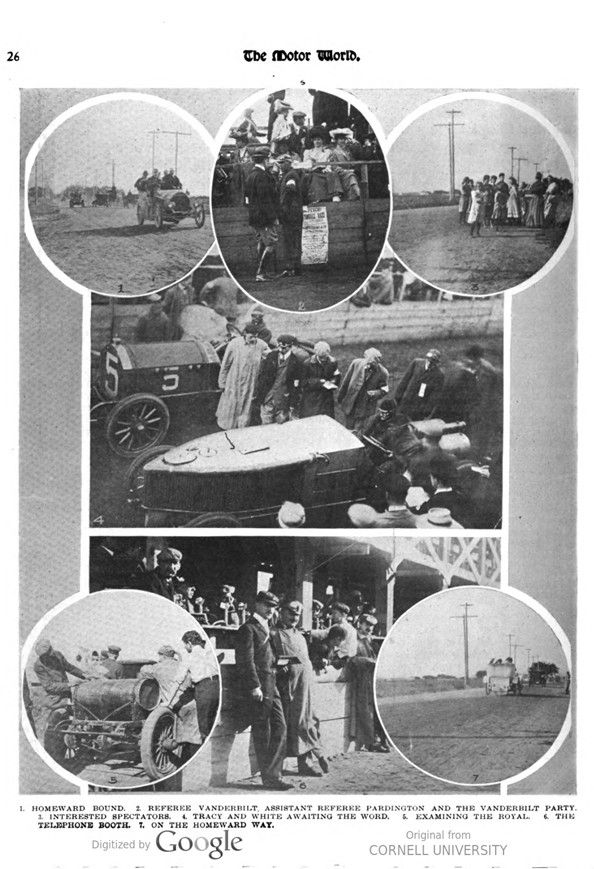

His victory has been heralded in so many places in such big, black type that he’s a queer sort of individual who does not know that very, very early in the morning of September 23 Bert Dingley, driving A. L. Pope’s 60 horsepower Pope-Toledo, „skiddooed“ over that 113.2 miles of Nassau County highway at a clinking pace-2 hours and 50 seconds, equal to 56¼ miles an hour, beating the second man, Joseph Tracy, in Dr. H. E. Thomas’s 90 horsepower Locomobile, by a scant 59 seconds.

In their settings these big road races differ little one from the other. The men, the cars, the incidents, the sidelights only – or chiefly – are different. The night before men in motor cars and men not in motor cars gather in large numbers at the hostelries near to the starting point. Some of the men sleep; some drink themselves to sleep; some sleep not at all. All these races start at about the time the hens are leaving their roosts, and long before the first cock has crowed or the sun has lifted the mantle of night all men, bright eyed and heavy eyed, native and visitor, are astir. Motor cars, their big, bright orbs piercing the gloom, fill the roads, and there are horse drawn wagons and bicycles and Lotor bicycles and men, women and children afoot – all, all trending toward that long, unpainted pine structure denominated a grandstand.

There they stop; there they scatter-cars are parked, many men and a few women seat themselves in the stand; more of them range themselves on either side of the road. Men with broad ribbons on their left arms dart hither and thither or loll in waiting idleness. They are the officials. Native yokels with a fluttering ribbon pinned on their coats stride up and down. They are the special constables, full of their brief authority. There are other natives – they bear a red or a yellow flag, or both. They are the signalmen – the men who give the signs of safety or of danger, to which few give heed. Like the constables, the race is placing an honest dollar in their pockets that otherwise would not be there.

The first faint streaks of dawn find eight or ten or a dozen big belching motor cars containing each two men in more or less fantastic dress, near or nearing the grandstand – the starting point. They are the contenders – the centres of interest. Gaping crowds stare at them or gather round. Most of the men are white faced-their skins are suggestive of paste. Obviously they are nervous and are seeking not to show it. The Carry this picture in your mind’s eye and you have a picture of the setting of all these great races-a picture of the setting of the race of Saturday last. In small wise does this setting differ here or abroad. strengthening day may disclose a background of hill or plain that is unlike, but all else – nearly all else – is the same. The day dis- closes that group of throbbing giants, compactly welded of steel and iron, awaiting the time and word that will cause them to bound forward on the long, black ribbon – the stretch of oiled road that narrows to nothingness in the far distance.

There were ten of them gathered there at Mineola at dawn on Saturday last. There should have been twelve. Carl Fisher, with his big Premier – No. 11 – and Tom Cooper, with his well tuned Matheson – No. 10 – were the absent ones. The Premier could not „make the weight“ – 2,204 pounds and to make it the Cooper car had been fitted with a lightened lubricating system; it failed to serve; the engine overheated and „seized“ the day before, and damage enough was done to keep it out of the fray.

The ten that lined up for the honor of entering the race of October 14 and seeking to wrest from France the massive silver trophy carried from these shores a year ago were:

No. Car. Driver.

1. 50 h.p. Haynes Frank Nutt

2. 60 h.p. Pope-Toledo Bert Dingley

3. 40 h.p. Matheson Ralph Mongini

4. 40 h.p. White Walter White

5. 90 h.p. Locomobile Joseph Tracy

6. 60 h.p. Christie Geo. Robertson

7. 40 h.p. Royal Tourist Robt. Jardine

8. 60 h.p. Thomas M. Roberts

9. 60 h.p. Franklin W. F. Winchester

12. 75 h.p. Pope-Toledo H. H. Lytle

WATCH TICKS AND TENSION.

They started in this order at two minute intervals. Each car bore on its front and on its sides the number that accorded with the order of its starting. Each was in readiness. Daylight-soft daylight-flooded the country. It was nearing 5:32 o’clock.

„Get ready, Nutt. You’ve got exactly five minutes,“ remarked Starter Wagner, watch in hand.

The influence of the remark swept the crowd. It buzzed with quickened interest, then quieted, while necks were craned and constables „got busy.“

„Four minutes!“ came from the starter; then „Three minutes!“ „Two minutes!“ „One minute!“ Then the seconds were counted in tens to ten seconds. „Five, four, three, two one!“ Then „Go!“ was fairly shrieked into Nutt’s ear. He went with a roar of explosive energy and a great puff of smoke from his heaven pointed exhaust.

Ten times did the starter repeat these words. Dingley, looking like a night gowned monk, was the next to hear them; then were they tolled off to Mongini, the one foreign driver in the race. Walter White, soft skinned and never more truly named, in his low shoe shaped craft of white went next – or perhaps „went“ is not the best word. The day before he and his car had had a nasty spill in trying the course. Some damage had been done, but it had been repaired; it was not an auspicious prelude for the man and the car on which high hopes had been set. White heard the „Go!“ An instant before a Motor World man had glanced at his steam dial; the hand was dancing at the extreme pressure, 1,200 pounds. When at the word this tremendous force was applied something went. It was not the car. There came a plume of white smoke, a dull thud, and the great white shoe simply coasted away from the line. It stopped a hundred yards beyond and was instantly surrounded by a curious crowd. The toggle joint of the universal shaft had broken. It was a bitter portion. But the crowd had no eyes for the unfortunate. Tracy, with his thundering Locomobile, was on the line belching blue fire. The unassuming Tracy, a veteran of last year’s race and of the race for the Bennett cup in France, was also much fancied. Popularly the victory was conceded to lie between Tracy, White and Lytle. While Tracy waited a man cranked and cranked and again cranked the car that was next to start, the direct drive Christie. It refused to respond. Willing hands laid hold of it. Once, twice, thrice it was pushed first backward, then forward, while Driver Robertson performed some deft. manipulations. Then of a sudden it volleyed like a battery of great guns, the roar mingling with that of the swiftly de- parting Locomobile, the white handkerchief that plumelike floated from the driver’s skull cap discernable through the smoke. The Royal, the elongated Thomas, the high built, buckboardish Franklin (each in order) got off without incident. Only Lytle, another veteran and another prime favorite, remained. What were his thoughts? The question was quickly answered.

LYTLE GETS HIS GUM.

„Gum? Gum? Who has any gum?“ It was the alert Pardington, assistant ref- eree by title, almost referee in fact, who spoke. There was no response.

„Gum? Gum? Mr. Lytle wants gum,“ he repeated through the short megaphone he carried and directing it in several directions.

Several hands dived in several pockets. One of them fished out a packet of the chewing material, and Lytle was made happy. A moment later the little man in the big car heard „Go!“ yelled into his ear. For a brief moment his car refused to budge. He had not released the brake. Another moment and he was off. The struggle was fairly on.

——————

At eleven points on the course telephones had been placed, each connecting directly with a ‚phone at the starting point. The latter ‚phones were ranged in a row in the „first story“ of the double decked press stand, situated exactly opposite the grandstand. At each ‚phone there was an attendant, who kept his car glued to the receiver. There was an official at each of the other telephones on the route, and a lineman with his kit strapped on a motor bicycle ready for instant duty in case of interruption. As was the case during the race last October, this telephone service kept the grandstand and vicinity well informed of all that was occurring. The information that came over the wires was promptly shared with the public. The official announcer repeated all messages through his megaphone.

„No. 1 (Nutt) passed Jericho at 5:37,“ was his first announcement.

„No. 2 burst his tire at Jericho,“ which came a few minutes later, caused the first ripple. It marked the undoing of the un. fortunate Christie car, and also, remarkable to relate, the only tire trouble of the race. The Christie driver later telephoned for permission to change a wheel, and the permission was granted with reservations. The change was made, but an hour was lost in doing so and the car, of course, was never a real factor in the contest.

Before he had started the message, „No. 2 passed the Guinea woods at 5:47,“ conveyed to Lytle – and to the crowd – that his stable mate, Dingley, had passed Nutt and was in the lead – a lead that he never lost save for a few brief seconds on the third round, when Tracy, in point of time, was clocked four seconds to the good.

The message also excited the curiosity of Referee Vanderbilt. When he heard it he approached a man who held a map of the course.

„Where are the Guinea woods?“ he inquired, and this despite the fact that his country estate is little more than five miles removed from them. The location of the woods was pointed out to him.

DINGLEY LEADS ON FIRST ROUND.

Possibly because the well informed Pardington was at his elbow Mr. Vanderbilt was less in the public eye than was the case last October. He mingled less and did not even look so chipper, but he wore the same old black satin smoking jacket with quilted lapels that he wore a year ago, and apparently the same riding breeches and puttees. He shuttled between the telephone booth and the box in the grandstand, in which were seated Mrs. Vanderbilt and a party of her friends. In the adjoining box were Albert L. Pope, whose car Dingley was driving; Arthur Pope, Charles E. Walker, H. A. Lienhardt and other of the Pope officials and lieutenants.

The message from the Guinea woods had quickened their interest, and when the first cry of „Car coming!“ reached their ears, and a few moments later the Pope-Toledo, with the big number „2“ painted on its radiator, could be plainly discerned, the smile that followed lit up the surrounding boxes. When Dingley dashed past there was a hearty hurrah. When the megaphone announced 25:58 – away inside a mile a minute – as the time A. L. Pope was so inexpressibly happy that he shouted:

„How is that for California?“

Dingley, be it understood, is a Californian.

Men who held stop watches glanced at their pieces again and again, and shook their heads as the announced time dawned on them. Several made their way to the officials, but it was quite a while before the correction was announced. There had been a mistake made of two minutes. The correct time was 27:58-and, notwithstanding, better than sixty miles an hour.

EXPANDING SMILE ON POPE FACES.

With each succeeding message – save one – and each succeeding appearance of Dingley the Pope smile became more expansive until at last faces became too small properly to contain it. The one shadow fell on it when the message came from East Norwich that Lyttle, on the second lap, was down and out with a broken sub-frame. The first story had it that he had run into a tree; but this proved not to be the case. By the irony of fate the mishap occurred when he was moving not at hurricane speed, but at a crawl of not exceeding three miles an hour. He had slowed for oil, and an error of judgment in the manipulation of his clutch had caused the irreparable damage.

If Lytle caused the Pope staff a pang, before he did so he gave the grandstand its first and indeed its only real thrill. It was on what proved his first and last lap. The monotonous cry, „Car coming!“ was unexpectedly varied by a cry of „Two cars coming!“ And they certainly were coming, the hindermost gaining on the leader at every revolution. They could be seen a mile away. It was a pretty sight, and the crowd fairly throbbed with excitement. As they came nearer it was seen that cherubic Lytle was coming hotfoot after the bearded Jardine. In the twenty-eight miles he had made up the If six minutes that had separated them. Jardine knew that Lytle was so close on his heels he gave no evidence of it. He held the centre of the road. Fifty yards from the grandstand the big Pope-Toledo swung sharply to the left; it cut deeply into the softer going, and the next instant flashed past the Royal, gained the centre of the road and, while the crowd cheered, opened wider the gap with every bound.

The long, red Thomas, with its boyish driver, had passed but a short time, and as it passed it shed fragments of something. E. R. Thomas, of Buffalo, its builder, and H. S. Houpt, its entrant, were there, but if they discerned trouble their faces did not show it-not even when some of the „wise ones“ who had picked up the fragments and called out, „His battery box is broken.“ The car was running well and had made a fast lap, but it made no more of the same kind. The battery box had, indeed, given away, and to even finish the plucky fellows in the car had recourse to carrying the battery in their laps-that is, in the chauffeur’s lap. Matters went from bad to worse. The coil also was injured, and the big car simply limped around the last lap. But two of the six cylinders were working, and instead of the deep base note that betokened full vigor there was but a weak irregular sound as of a giant seeking to stifle its sobs at its own helplessness.

E. H. R. Green, the great big, good-natured Texan, was there, too, to see his big wheeled, high bodied, eight-cylinder Franklin per- form. He saw it once, and then it was seen no more. But that once was enough to show that its speed was not sufficient for such a battle. It was moving well, but it lacked the dash of the others. It cast a shoe, or rather a bolt, on the second round, the bolt penetrated its big stomach – its gasolene tank – and through the big hole its life blood ebbed and then it stopped, not to go again until tied to the tail of a car with a good stomach. For nearly two hours it was lost. The telephone brought no word of it, and after all was over its big owner went scouring the country for trace of it.

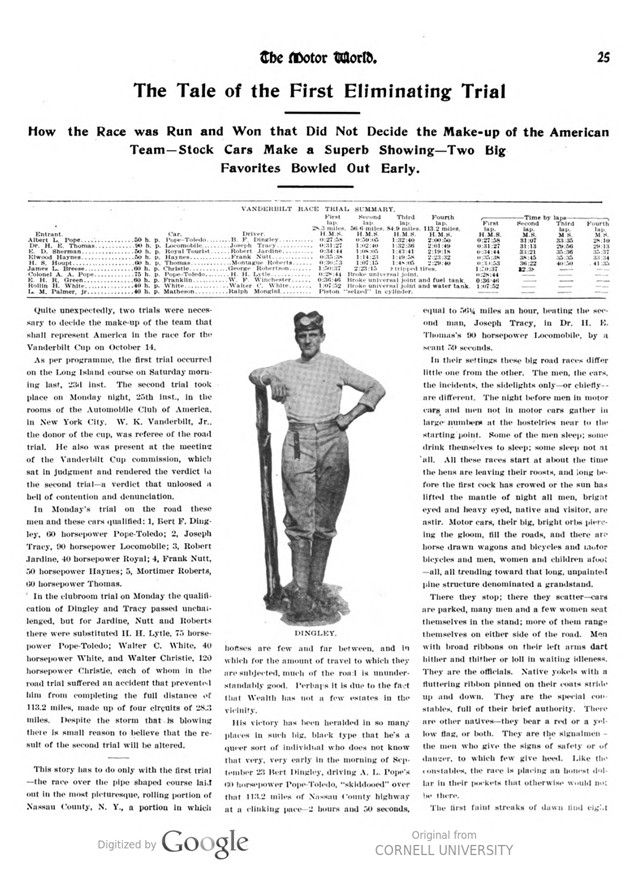

Photo captions, page 25 – 36

The Motor World. 26 + 27.

1. HOMEWARD BOUND. – 2. REFEREE VANDERBILT, ASSISTANT REFEREE PARDINGTON AND THE VANDERBILT PARTY. – 3. INTERESTED SPECTATORS. – 4. TRACY AND WHITE AWAITING THE WORD. – 5. EXAMINING THE ROYAL. – 6. THE TELEPHONE BOOTH. – 7. ON THE HOMEWARD WAY. – DINGLEY, VICTORIOUS, DASHING DOWN THE HOMESTRETCH.

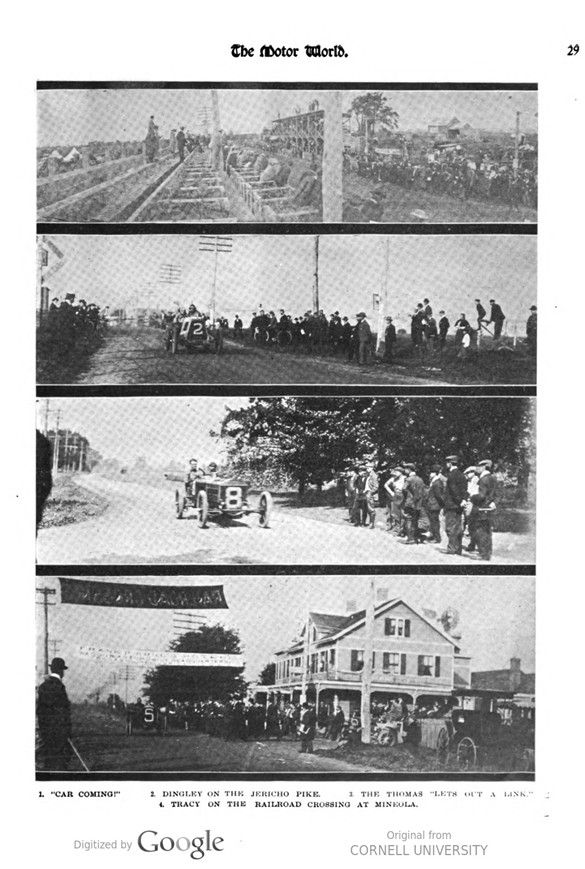

The Motor World. 29

HOTELS HEADQUARTERS. – 1. „CAR COMING!“ – 2. DINGLEY ON THE JERICHO PIKE. – 3. THE THOMAS „LETS OUT A LINK. – 4. TRACY ON THE RAILROAD CROSSING AT MINEOLA.

The Motor World. 33

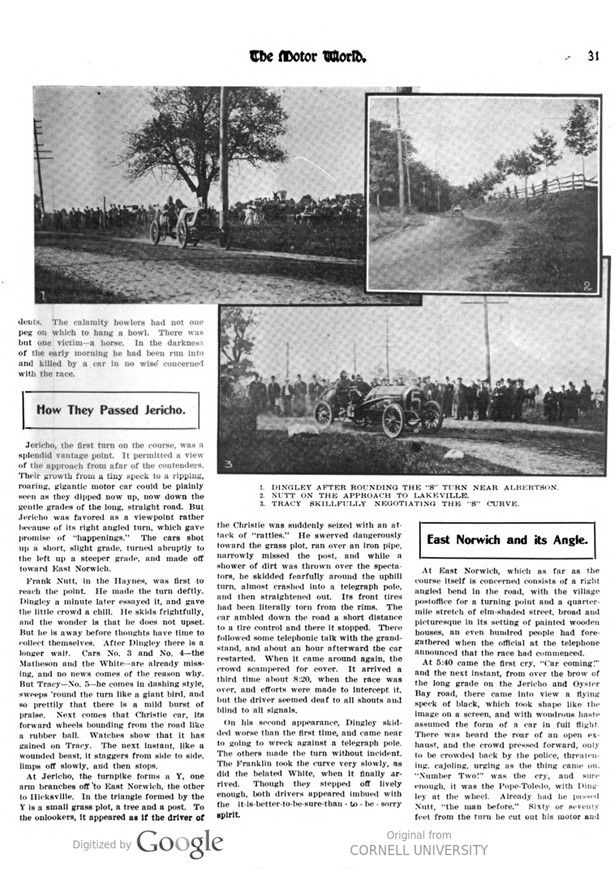

1. DINGLEY AFTER ROUNDING THE „S“ TURN NEAR ALBERTSON. – 2. NUTT ON THE APPROACH TO LAKEVILLE. – 3. TRACY SKILLFULLY NEGOTIATING THE „S“ CURVE

The Motor World. 32

NOT NIGHT GOWNED MONKS, BUT LYTLE AND HIS CHAUFFEUR.

The Motor World. 33

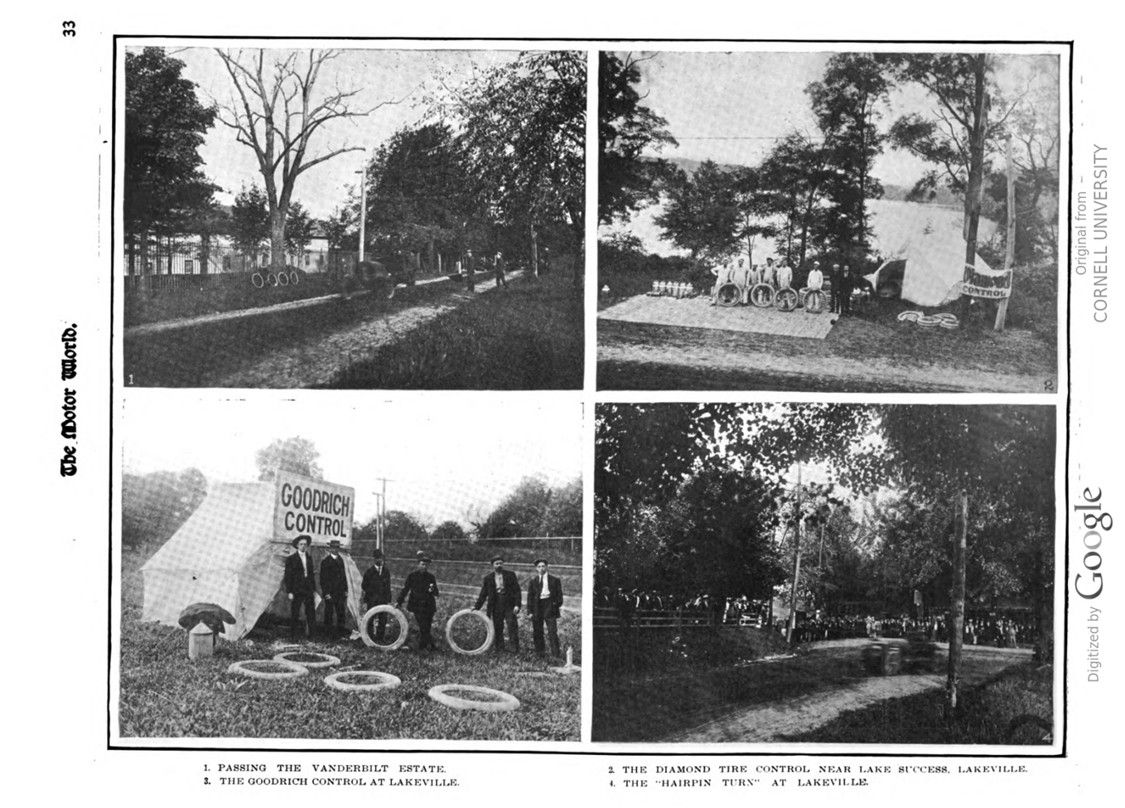

1. PASSING THE VANDERBILT ESTATE. – 2. THE DIAMOND TIRE CONTROL NEAR, LAKE SUCCESS, LAKEVILLE.

3. THE GOODRICH CONTROL AT LAKEVILLE. – 4. THE HAIRPIN TURN AT LAKEVILLE. 20

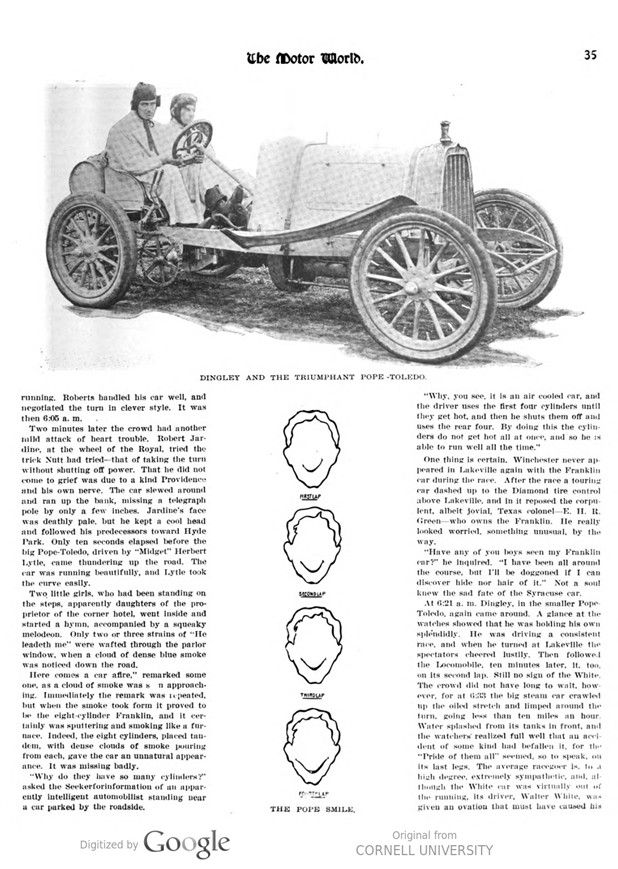

The Motor World. 35

DINGLEY AND THE TRIUMPHANT POPE-TOLEDO. – FIRSTLAP – SECONDLAP – THIRDLAP – FOURTHLAP – THE POPE SMILE.

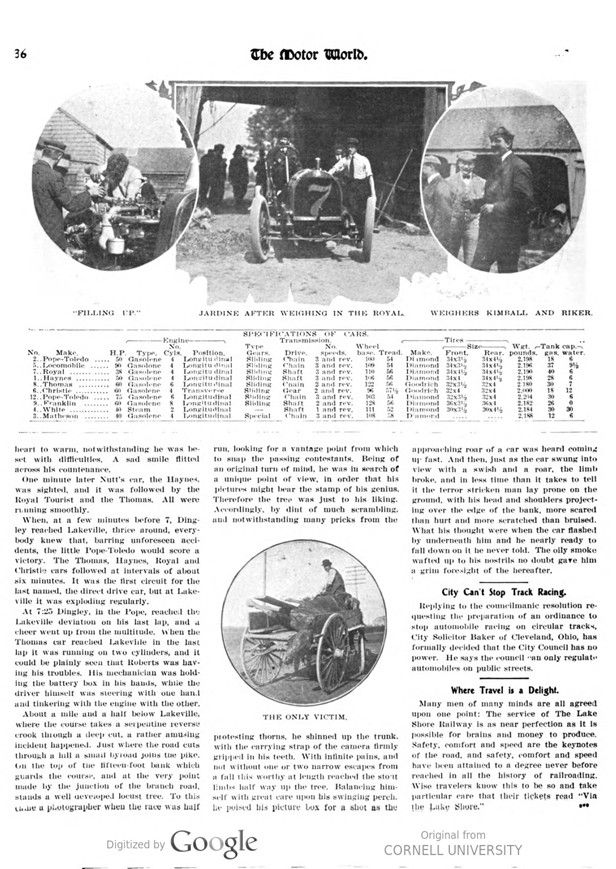

The Motor World. 36

„FILLING UP.“ – JARDINE AFTER WEIGHING IN THE ROYAL – WEIGHERS KIMBALL AND RIKER.

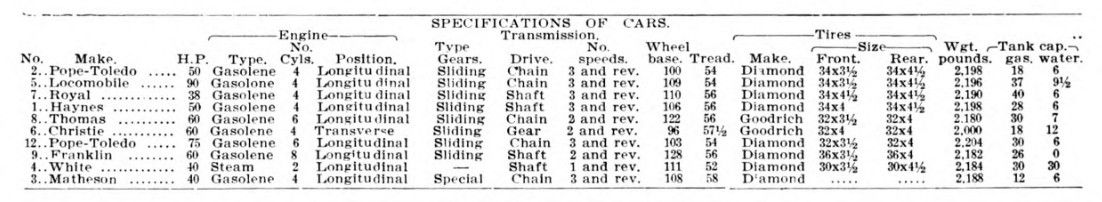

SPECIFICATIONS OF CARS. – THE ONLY VICTIM. (a horse)