Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Motor Age, Vol. XXXVII, No. 24, June 10, 1920, page 11 – 13

Small Engines Cut Pit Stops in Half

Indianapolis Race Proves Efficiency of 183 Cu. In. Piston Displacement Engine, Which Is Only Slightly Larger Than the Ford Power Plant and Develops Over 100 Hp.

BY ROY E. BERG

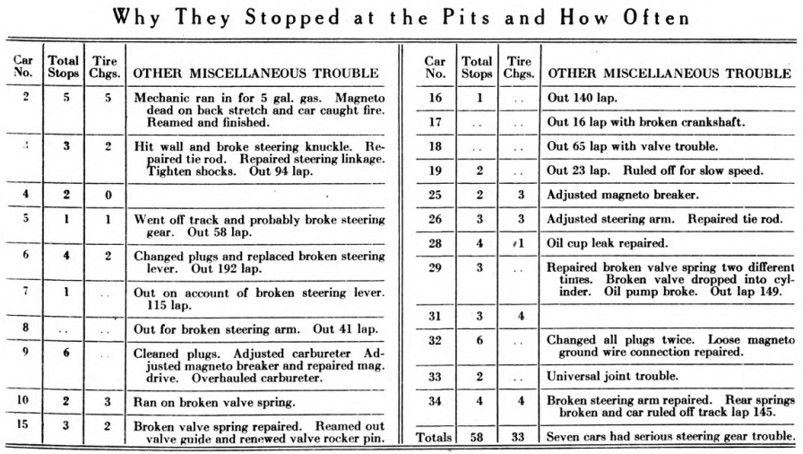

THE most important lesson that the Indianapolis race taught, is that the light cars with their small engines, though really slower in maximum speed than the large cars of last year, were faster as far as averages go, because of their consistency. In last year’s race there were sixteen cars that qualified at better than 95 m.p.h. In this year’s race only five qualified at 95 m.p.h. or better. In last year’s race seven drivers qualified at better than 100 m.p.h. In this year’s race not one driver qualified at better than 100 m.p.h. Notwithstanding this, last year’s average of 87.95 m.p.h. was bettered this year to 88.55 m.p.h. The reason for the higher average speed is seen in the consistent performance of the smaller cars. Last year the cars made 106 stops at the pits for gasoline, oil, water, tires and mechanical repairs. This year only fifty-eight stops were made for various reasons. Tire trouble was greatly reduced, for during the whole race only thirty-three tires were changed. Last year this figure was more than doubled for sixty-six stops were made for tires alone, and it is probable that during many of these stops more than one tire was changed. It is also worthy of note that the winning car in this year’s race did not change a tire during the whole 500 miles. The winning car, in fact, made but two stops, and these were for gasoline and oil. Better ignition, was employed on the winning car and no trouble was encountered from this source.

The first stop at the pits was made by Ralph DePalma, the famous Jinx artist. A right rear tire blew and this was changed in twelve seconds, which constitutes a record on the Indianapolis track. This bit of trouble was experienced during DePalma’s first lap, which made it disconcerting to say the least. Outside of the stops for tire changes, the next greatest offending member was the steering gear mechanism. Many of the cars suffered from this trouble. Five of the cars entered by the Wm. Small Co., the four Monroes and the three Frontenacs, suffered steering gear trouble. The Meteor, and the Ballot driven by Chassagne, also suffered steering gear trouble. Spark plugs were offenders to a slight degree, but not to the extent that the ignition apparatus was. Especially noticeable were a few cases of ignition trouble; the magnetos not performing as they should have. It is probably true that the extreme high speeds of this year’s small engines was the chief contributing factor for the magneto trouble. Valve trouble and other miscellaneous items contributed to the total, and made necessary the fifty-eight pit stops.

DePalma was credited with a case of bad judgment for letting his fuel run out on the track when his mechanic came running in for 5 gal. of gasoline. Ralph had calculated that he could successfully complete the 500 miles on one tank of gasoline, which he did. The cause of the trouble which he had was due to one of the two magnetos. Ballot car which Ralph drove was equipped with two magnetos, one for each set of four cylinders. Ralph found that his engine was spitting back through the carbureter of the rear set of cylinders, which led him to believe that his gasoline was just about out. Finally the engine kicked back energetically and the carbureter caught fire. After resuming the race the engine again caught fire. So that he might finish and not have the engine burn up De Palma removed the plugs from the rear four cylinders and finished the remaining few laps of the race on the other four.

The second lap of the race, the Richards car driven by Bolling arrived at the pits with a silent engine. Upon examination it was found that a ground wire from the magneto was loose. All the plugs were changed, though, before the trouble was found and this caused quite a delay for this car’s average for the first twenty-five miles was only 39.1 m.p.h. The next stop was made by the Revere, which came in for a rear right tire. The change was made in 16 seconds. In the seventh lap of the race, Roscoe Sarles in the Monroe came in for a left front tire.

The Gregoire, driven by Porporato up to this time had been driving very slowly. The engine, to all appearances, was functioning properly, but the car had no speed. It was evident that the gear ratio was too low, and this factor contributed largely to the discouragement of Jack Scales, who was to pilot the other Gregoire. These cars came with only the one gear ratio for the rear axle and it was not possible to get other gears made in time. The Gregoire, which did appear on the track, seemed to be improperly shocked, for on the turns the car behaved very strangely. This was the reason why Porporato was flagged in for consultation concerning the antics of the car. The snake-wriggling fashion that the car had made it very dangerous for other cars to pass it.

At the seventeenth lap, Andre Boillot was seen walking in. His Peugeot car experienced engine trouble and it is thought that the crankshaft broke, at least this is what the mechanic said when questioned. The Peugeot cars entered by Jules Goux and driven by Goux, Howdy Wilcox and Boillot are not to be confused with the Peugeot driven by Ray Howard. Goux’s cars were entirely new creations, with several new wrinkles incorporated in their construction which apparently needed further development before attempted in any car to be tried on Indianapolis track. These cars had three camshafts, and five valves per cylinder. Two of the valves were exhaust and the other three intake. At low speeds, the third camshaft did not operate the auxiliary intake valve, but at high speed, when greater power is needed, the driver shifted a small hand lever, which threw the third valve into operation. With all due respect to the intentions of the designer we do not feel that the construction was the best. The principle was ideal, but the application did not prove practical. These three cars lasted only a short while.

Car number nine, the Peugeot driven by Ray Howard, came in on its twenty-third lap with an occasional explosion sounding from its exhaust. Much diffculty was experienced in fixing this car so it would run at all. At first it was thought the spark plugs were causing the trouble, and the first three were replaced, with no noticeable improvement in operation. Next the carbureter was readjusted, the jets examined and finally the magneto was subjected to scrutiny. The ignition was retimed, and in all a good many things were done and the car was finally started after a long delay. It was finally discovered that one of the small jets from the carbureter had been sucked up into the manifold. So long was this delay that the average speed up to the seventy-five-mile mark was only 22.5 m.p.h. This car experienced considerable trouble during the tuning up periods. Two complete engines were on hand at the garage. The car was tried out very nearly every day for two weeks before the race. Different magnetos were tried. New carbureters and various sized jets were experimented with to no good effect. When finally the day of the race dawned this car, which was one of the first to put in an appearance at the track, was not ready. At a later stop, a whole new camshaft was placed in position, but this did not seem to improve conditions very much.

At the forty-first lap Art Klein retired with a broken steering knuckle lever. This was the beginning of the steering gear trouble. Klein’s Frontenac overturned when the steering lever let go and wrecked the car beyond repair for that day.

The next three or four stops were made for gasoline and oil, but the next stop for mechanical trouble was made by the Meteor, and steering gear trouble was the cause. The car came into the pits with the mechanic holding the steering knuckle on one side with his hand, and on the other side with his handkerchief. When the steering lever let go the tie rod suffered, with the result that both of these members were replaced. This was the fifty-fourth lap for this car. After this, steering gear trouble occurred regularly. While it is true that Chassagne in the Ballot suffered steering gear trouble also, this trouble was not the fault of the gear. On the back turn Chassagne was placed in the predicament where he had to run into the wall or take to the grass. He chose the latter alternative and his tie rod suffered.

Examination of the steering lever on car number seven, the Frontenac, driven by Benny Hill, showed that a progressive fracture had occurred in the steel. The breakages of steering mechanism were of an unexpected nature. The grade of steel used in these parts was not at all suitable to the purpose. Steel used in steering gear levers should bend but should not crack off brittle, and this is what most of the cars experienced. Accidents of this type prove very dangerous, and it seems that had more metal been provided to take the strains, the cars would have made even a better showing than they did. Weight saving by reduction of metal at places where stresses mount to maximum is poor policy.

The Duesenberg number twenty-nine, driven by Eddie O’Donnel, came in for a new set of plugs, and after a general inspection, started off without one of the plugs. The plug was hastily replaced and then started off. The Revere, piloted by Henderson and later by Tom Alley, was the victim of much valve trouble. Alley had the rocker-arms off, and the valve guides out. He reamed out several guides, did a little general rebuilding, but the car still persistently missed. Tommy Milton in the Duesenberg ran for a considerable time on a broken valve spring.

On the whole the cars made a very creditable showing. Last year we made a plea for the smaller engine. With the coming of the reduced sized power plant we have found out that performance has actually been bettered. Engines of 183 cu. in. piston displacement, which is only slightly larger than the Ford engine, can be made to develop over 100 hp. Applying some of these principles to our stock car engines we should soon have power plants of greater enduring qualities, capable of exerting a tremendously large effort with a minimum of fuel consumption. The question of economy must soon be of paramount importance and the small-sized engine will greatly aid in the ultimate solution of the problem.

Photo captions.

Pag 11:

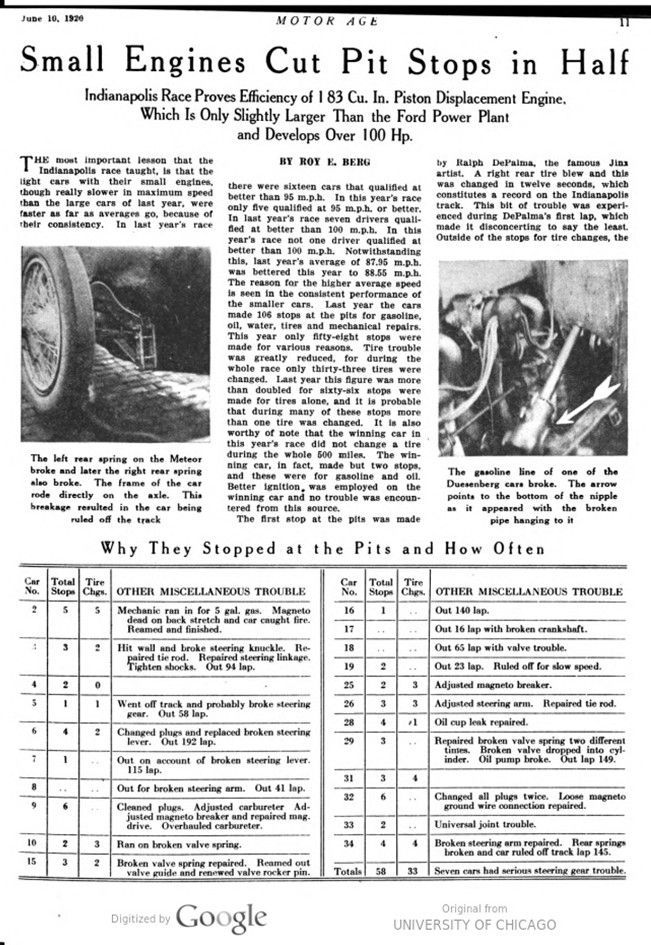

The left rear spring on the Meteor broke and later the right rear spring also broke. The frame of the car rode directly on the axle. This breakage resulted in the car being ruled off the track

The gasoline line of one of the Duesenberg cars broke. The arrow points to the bottom of the nipple as it appeared with the broken pipe hanging to it.

Why They Stopped at the Pits and How Often

Page 12: Repairing the broken steering lever on the Meteor

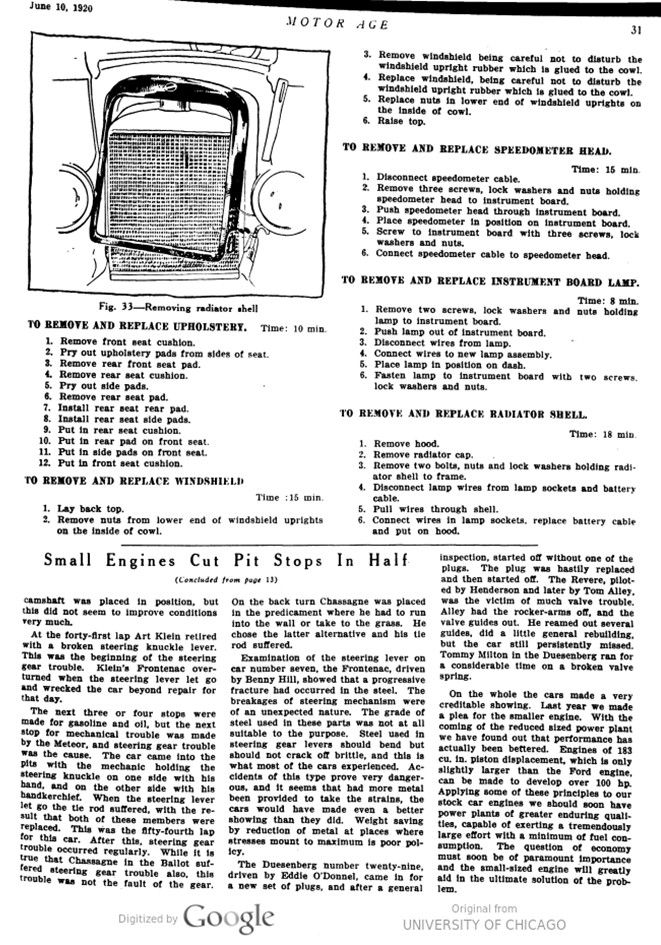

Page 13: Another case of a broken steering lever. This is one of the Joe Boyer’s Monroe with the wheel removed and a new steering lever being put in place

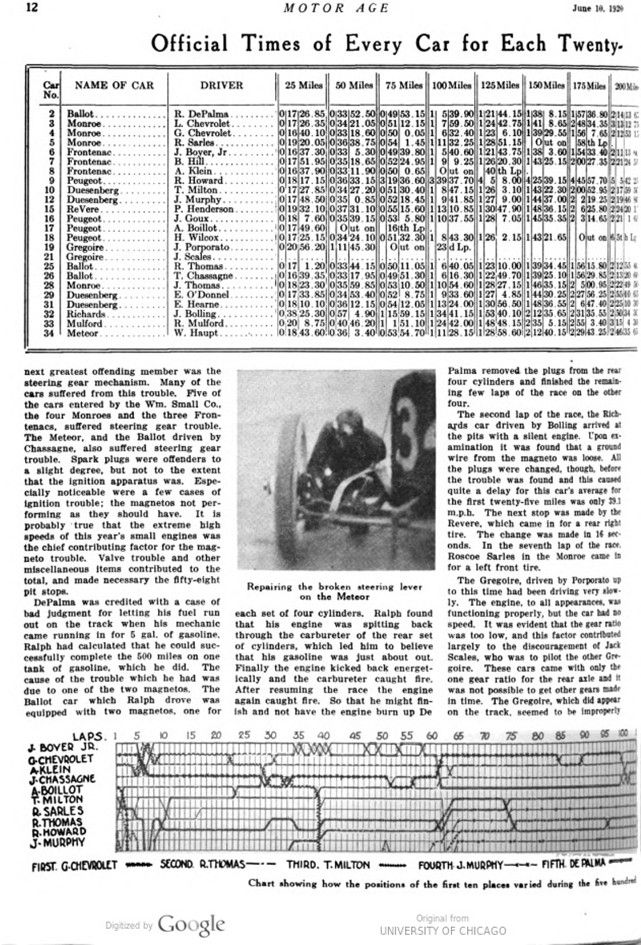

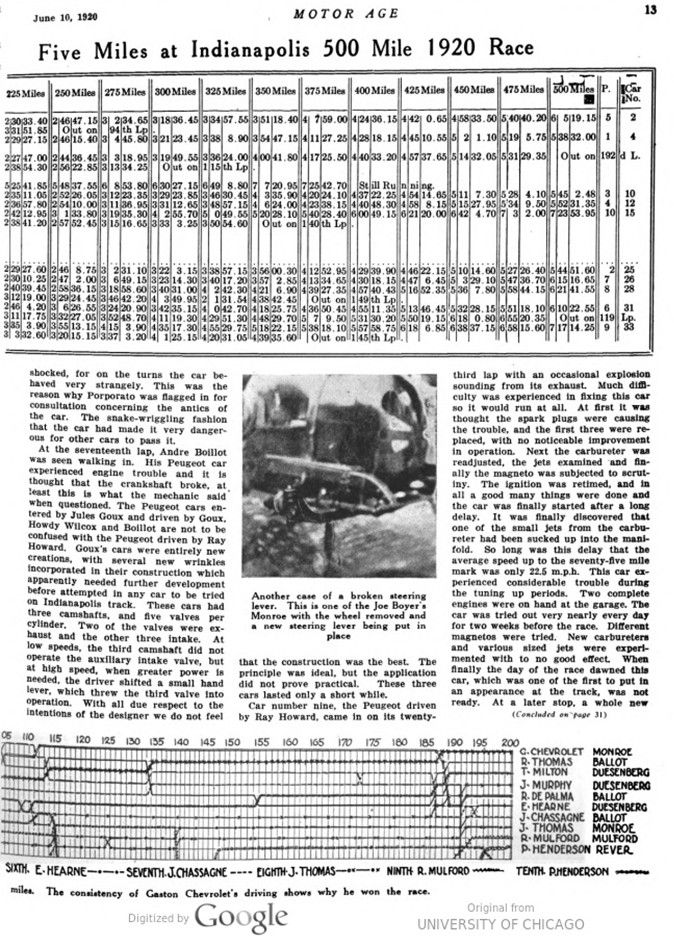

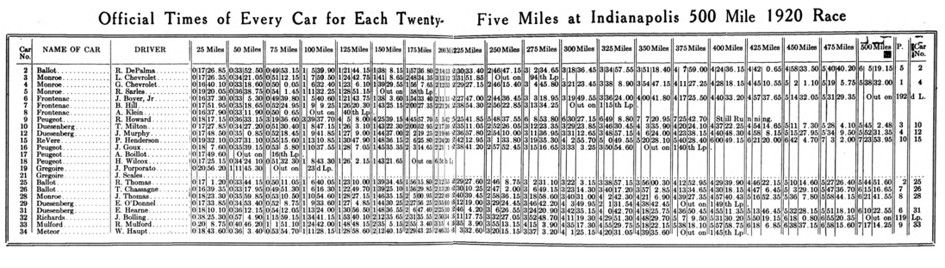

Official Times of Every Car for Each Twenty-Five Miles at Indianapolis 500 Mile 1920 Race

Chart showing how the positions of the first ten places varied during the five hundred