This one is a summary on the performances of the participating cars and an overview of mechanical issues during the 1911 Indianapolis Sweepstakes.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Motor Age, Vol. XIX, No. 22, June 1, 1911

Resume of Performances of Cars at Indianapolis – Analysis of the Mechanical Mishaps During Race

SO far as the public was concerned, that is, that public that goes to a race to see cars perform, the honors weren’t all to the fastest cars. The medium-powered machines came in for a big share of the honor by their very consistent running. The performance of these cars was a revelation to everybody. No one expected that they would stand up so well; fortunately they surprised their friends as well as enemies. Before the start of the race wagers were being made that ten cars would drop out in the first 100 miles and that when the race was half over more than half of the cars would be out. This was far from the case, because when the race was 100 miles gone only one car was eliminated and that was Greiner in No. 44 Amplex, the two-cycle machine which was wrecked by throwing its demountable rim. With this exception all of the other cars were running well, there was little if any heating, and all of the stops that were made for changing tires.

Weeding Out the Cars

The greatest elimination of cars came from 100 miles to 300. The first serious trouble that showed itself was due apparently to crystallization of parts. Steering knuckles, crankshafts and connecting rods were giving way. The grandstand spectators had three examples of steering knuckles or tierods breaking on the home stretch. The first was Fiat car No. 18, driven at the time by Parker. The knuckle gave way just at the start of the homestretch. Parker guided the car for a distance, then it tore into the grass at the ouside of the track and continued its perilous trip to the overhead bridge before it finally was stopped. It was pushed down the track to the repair pit, a new part put in and taken on the course again with Hearne at the wheel. It finished the rасе. Those who watched the preliminary practice had discussed the matter of crystallization of steering parts and it was stated that many of the steering parts in this car were used in previous races. It added one more bit of evidence to the fact that parts subjected to great and incessant vibration in a racing car should be changed before subsequent races.

Steering Parts Crystallized

The Case cars suffered from crystallized steering parts. Strang, driving No. 1, had a tierod let go coming down the home stretch. The car dashed into the dirt at the inside of the track, but Strang piloted it free from the fence until it was stopped not 30 yards from the end of the grandstand repair pits. No. 8 Case had a steering part crystallize coming down the home stretch. The car swerved from side to side but finally was stopped in the middle of the course just at the lower end of the grandstand and opposite the repair pits. The mechanician jumped out to assist in pushing it to the pits when the mixup that eliminated two other cars happened. The No. 7 Westcott driven by Knight was coming down behind the Case and to avoid striking the Case mechanic it was necessary to turn left and go between the Case car and the pit. In doing this a sudden application of the emergency brake brought a skid, so that in passing the Case the Westcott struck the Apper- son standing at its pit and upset it, putting it out. The Westcott also was eliminated. The Case car withdrew.

Blowouts Play a Part

Accidents were responsible for two other cars being put out of the running, blown out front tires being largely responsible for the trouble. No. 34 Lozier, driven by Tetzlaff, was coming down the homestretch holding the inside. He had blowout front and had pulled to the inside of the course so as to come into the pit. Disbrow, driving No. 5 Pope special, was following him and he, too, had just had a blowout and was also going to cut to the inside. Tetzlaff pulled in in front of him, the Pope special spring horn caught the Lozier and turned it around on the track and then the Lozier turned over in the dirt on the side. Both cars were out. This made five cars eliminated by accidents.

Crankshafts Break

But the crystallization of parts already referred to reached further than steering parts. It attacked crankshafts and other parts. Aitken driving No. 4 National, a special racing machine, broke a connecting rod and was eliminated. Arthur Chevrolet piloting No. 16 Buick Special broke a crankshaft. Later in the race Caleb Bragg, driving No. 39 Fiat, was eliminated with a broken piston. Charles Basle, driving No. 17 Buick special, withdrew because of a cracked crankcase.

There were two eliminations due to lack of lubricating oil. The first of these was Grant in No. 19 Alco. He burned out a bearing at 125 miles and was out. The other case of lack of lubrication was Dawson, driving No. 31 Marmon. His case was pathetic. He had finished the second last lap, only one more circuit of the course remained. He stopped to put in oil. The motor was hot, due to lack of water because of a punctured radiator. The oil, however, came too late and he was not able to complete the circuit and so went his chances of earning $2,000 which would have been his for running in fourth place.

This is a small list of breakdowns out of a field of forty cars and speaks volumes for the present American motor car. It is not a distant memory to the times when motor troubles and a score of other ones kept the grandstand pits filled, but such was not the case today. It should not be assumed from this that there were not any mechanical troubles outside of these. Several of the cars had minor troubles. Basle had a steering gear get tight on his Buick and it had to be loosened. There were many cases of slight troubles that cost some of the cars 2, 3, 4 or 5 minutes.

Starting the Field

One of the important details of the race was the starting of the cars, forty of which got away in good shape. The width of the track was such that perhaps a dozen could be lined up across it and so there would have to be three or four successive rows. To avoid this the cars were arranged in rows of five each, there being eight rows, one behind the other, with the cars in each as follows:

Pacemaker 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 23 24 25 26 27 28 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 89 41 42 44 45 46

Carl G. Fisher acted as pacemaker and led the cars once around the circuit at a speed of 40 miles per hour. The left-hand car in each line acted as pacemaker for the line and by this means a space of 60 or 100 feet was maintained between the lines. At the end of the first lap Fisher withdrew and the race was on. This method gave the cars in the first line a big advantage over many of those in the back lines and when No. 46 crossed the line, No. 4, which was in the front line, was 1 mile in the lead. The start did not make any difference in the result because the big fight was between cars No. 28, 32 and 33, which, as it happened, were all in the same line and so started on even terms. This method of starting got away from the smoke nuisance which invariably takes place when a lot of cars are started at once.

Undoubtedly what saved many of the cars was the shock-absorber protection taken. Harroun on his Marmon Wasp used two sets of shock absorbers, that is, eight in all. With these the car held the track beautifully and there was not any of the pounding of the front wheels that was noticeable on several other cars. also is a fact that the majority of those cars which did a great deal of pounding had steering gear troubles. The race could not otherwise but teach a few makers the necessity of reducing vibration to a minimum. It is just as important to reduce vibration as it is to have good tires.

Drivers Were Prepared

Compared with many former track and road races it was interesting to note the freedom from gasoline leakages, spark plugs, etc. The long period of training on the speedway had brought out many of the weaknesses, so that it is problematical if ever before did cars enter a race better prepared. It could scarcely have been better, excepting in a few cases, as already mentioned. Not only were the cars well prepared but the drivers had studied the track and knew what parts were smoothest and wore the tires least. The smooth qualities were nearly the undoing of many about the middle of the race, before the management started putting sand on the course. It was so slippery that the drivers could not open the throttle wide on the back stretch; if they did the rear wheels wanted to get in front of the forward ones. After the sand was applied slipping was over and the speed average increased.

Naturally because of the bonuses offered by the carbureter concerns, there was considerable interest displayed in the equipment on the cars that finished in the money. The extras in this line run into a considerable sum. The Rayfield carbureter purse totaled $3,000, of which $2,000 was to go to the winner provided he used the product of the Findeisen & Kropf Mfg. Co.; $500 to second; $300 to third; $200 to fourth. Wheeler & Schebler hung up $2,500, which was to be given to the winner if he had on a Schebler carbureter. The Columbia Lubricants Co. offered $1,000, divided $500, $250, $150 and $100 if Monogram oil was used by first, second, third and fourth. The Remy magneto purse amounted to $1,000; the Red Head spark plug fund to $400, divided $250, $100 and $50; the Dorian rim purse, $250, $150 and $50, and the Splitdorf magneto purse, $3,100, split $1,500, $750, $500, $250 and $100.

As reported, Harroun’s Marmon was fitted with Firestone tires, Remy magneto and Schebler carbureter, so he realized a small fortune, when it is remembered he cashed $10,000 for being first. Mulford carried a Rayfield carbureter and Bosch magneto. Bruce-Brown had on a carbureter made by the Fiat people and used a Bosch magneto. Wishart used a Mercedes carbureter and a Bosch magneto. De Palma drove with a Simplex carbureter and Bosch magneto. Merz in the National had on a Schebler and a Remy, while Turner in the Amplex pinned his faith to a Schebler and Bosch. Cobe in the Jackson had the Schebler-Splitdorf combination, while Belcher in the Knox used a Rayfield carbureter and a Bosch magneto. Hughes in the Mercer, last one in the prize list, had on a Schebler carbureter and a Bosch magneto.

Record of the Drivers

Just how much Cyrus Patschke will get for assisting the Marmon to victory is not known, but certain it is he should not be forgotten when the division of the spoils takes place. Patschke contributed largely to Harroun’s success. When he relieved the little fellow the Marmon was chasing Bruce-Brown and when he was ready to step out the Marmon had a good lead. Harroun perhaps was wise in taking the rest he did, for he has not the robust constitution some of his rivals have. Indeed, it hardly is likely he could have continued much farther.

On the other hand, Mulford and Bruce-Brown apparently were in prime condition, neither man having suffered from the long grind. Both of them had gone the entire distance and evidently could have kept on for some time. Wishart showed the strain of the long drive and at the end was nervous and inclined to be morose. He, too, went the full route, as did happy-go-lucky de Palma.

Although it was within the province of Referee Pardington to order drivers relieved, he did not find it necessary to exercise this right. In fact few of the drivers show any effects of the long race.

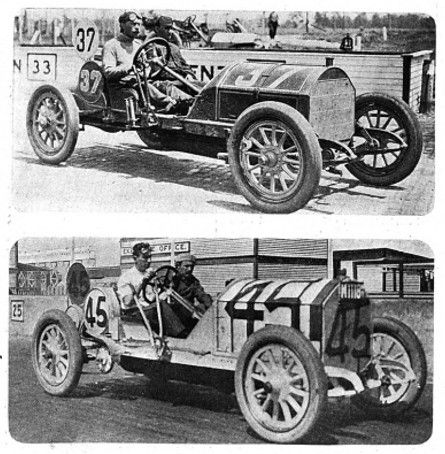

Photo captions.

Page 8 – 11

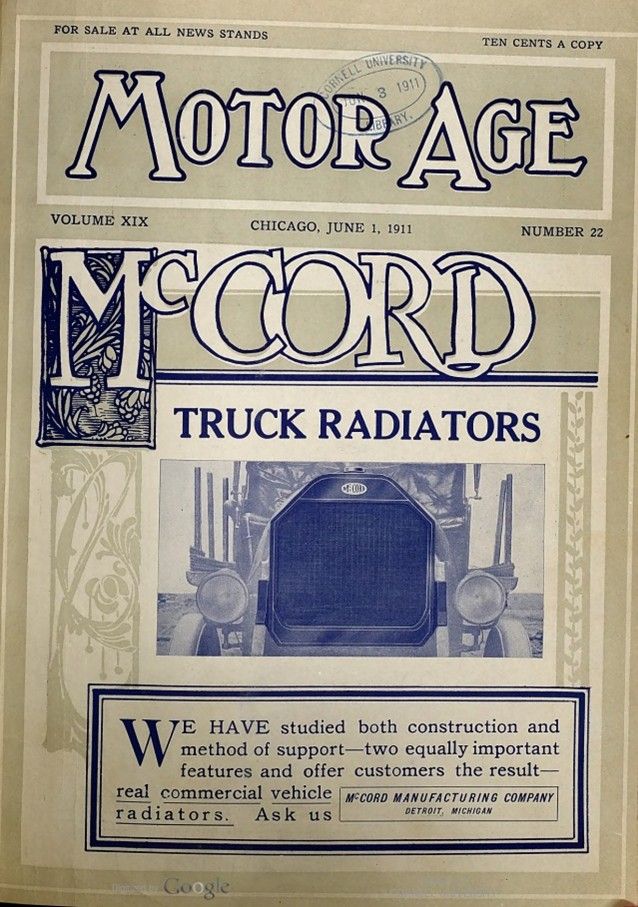

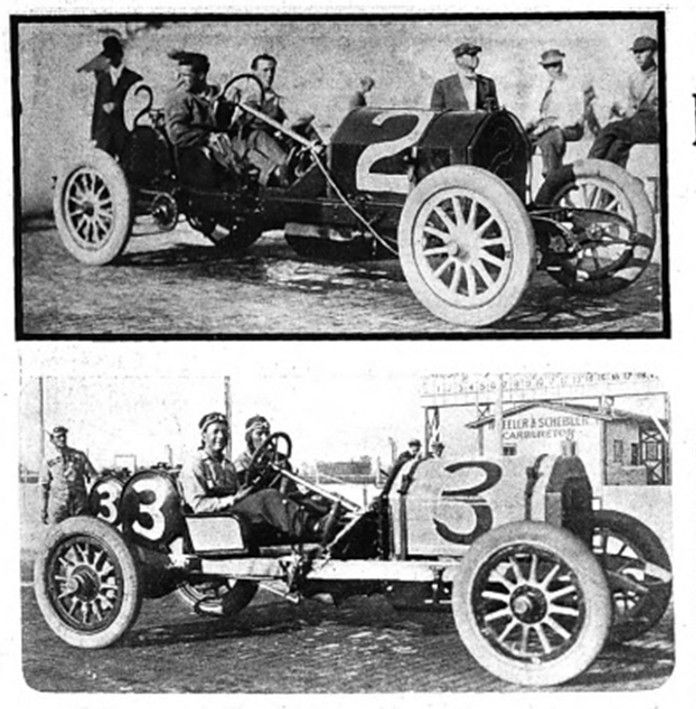

RALPH DE PALMA IN SIMPLEX – H. ENDICOTT IN INTER-STATE

TURNER IN AMPLEX – HUGHES IN 36 MERCER

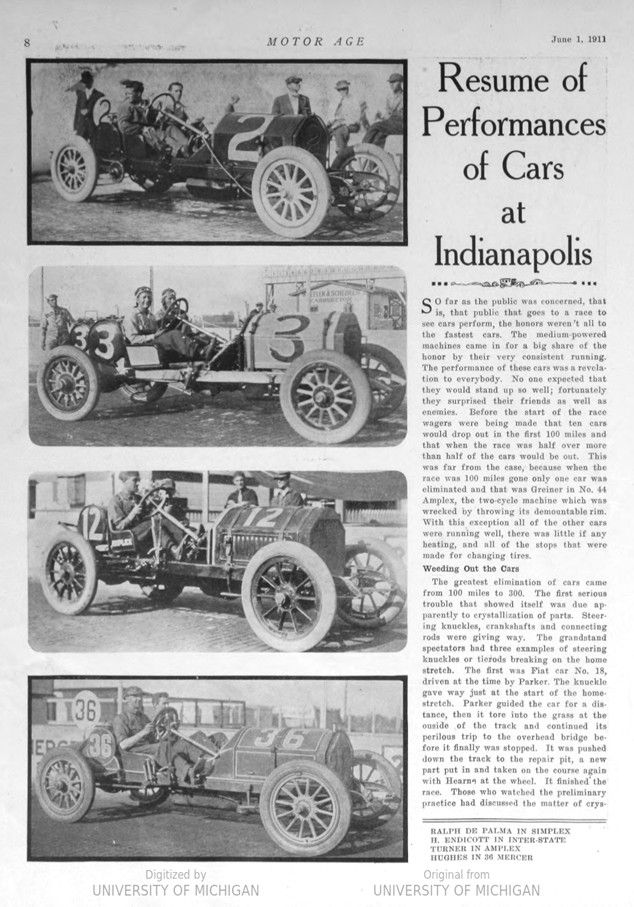

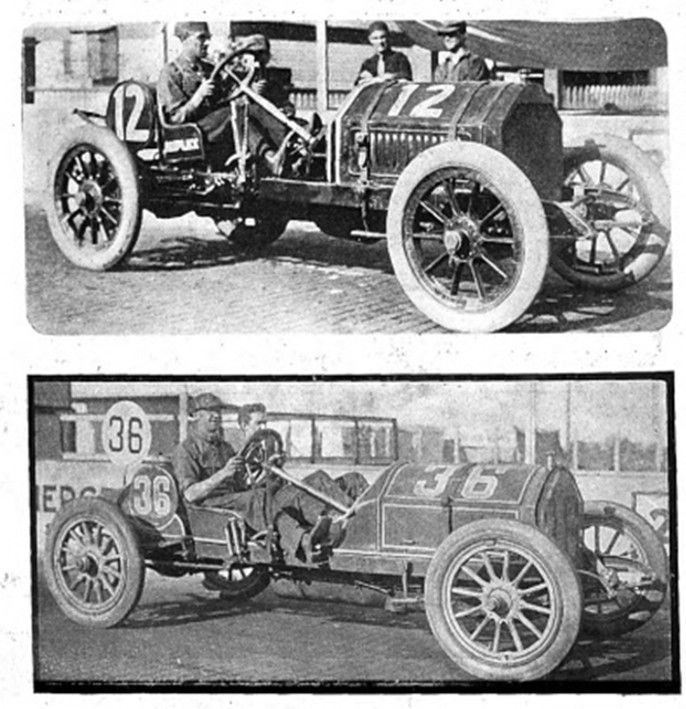

FRAYER IN FIRESTONE-COLUMBUS – BIGELOW IN 37 MERCER

BOB BURMAN IN 45 BENZ – FOX IN 6 POPE-HARTFORD 3

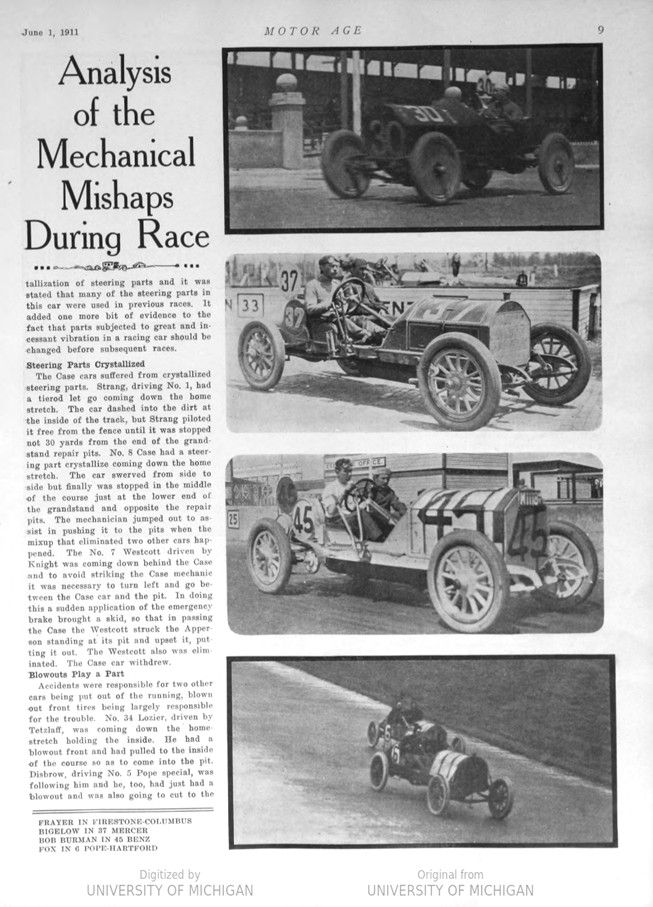

CHARACTERISTIC SCENE AT PITS, WITH MERZ’ AND WILCOX’S NATIONALS STOPPING

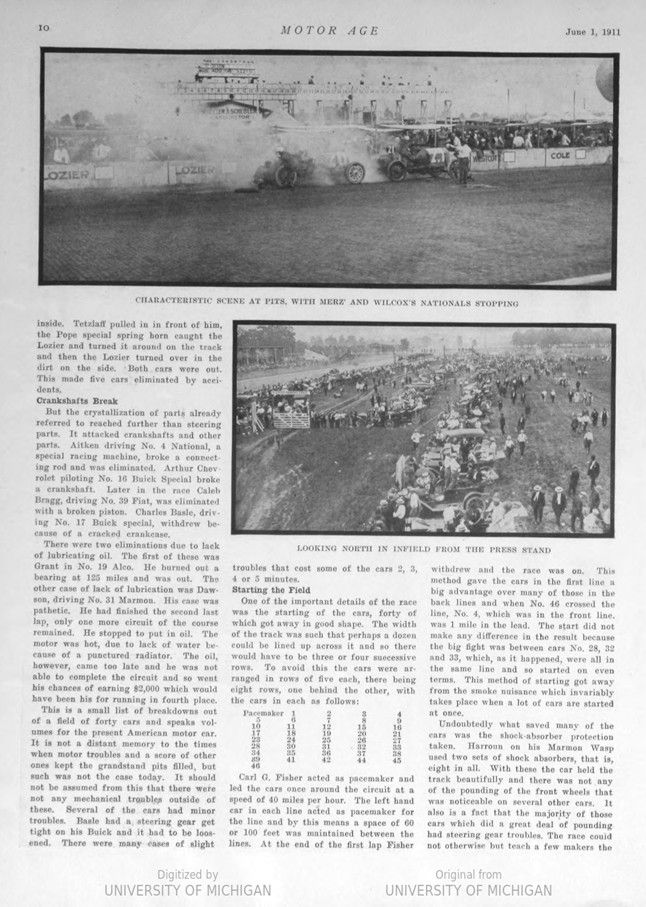

LOOKING NORTH IN INFIELD FROM THE PRESS STAND

SCENE IN HOMESTRETCH, DARK PORTION SHOWING OIL ON THE TRACK

PADDOCK SCENE SHOWING ACCESSORY HEADQUARTERS