This race report of Motor Age lightens not only the race, but it also points out the drivers and cars that were remarkable in the race.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

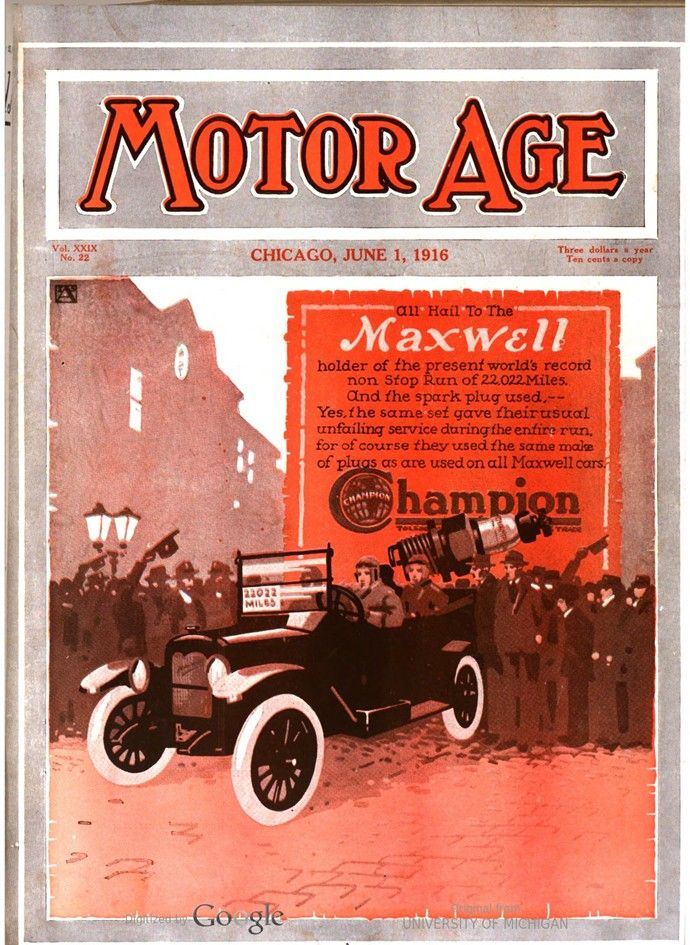

MOTOR AGE Vol. XXIX, No. 22 Chicago, June 1, 1916

Resta’s Peugeot First in Hoosier Classic

D’Alene in Duesenberg Second – Italian Not Pushed

By Wallace B. Blood

INDIANAPOLIS Motor Speedway, May 30 – Consistent plugging with practically no keen competition to face won first place and $12,000 for Dario Resta in his battle-worn Peugeot in the fifth annual Memorial Day classic on the Indianapolis speedway today. His time for the 300 miles of 3 hours, 34 minutes, 15.71 seconds, at an average speed of 84.05 miles an hour did not approach the speed set in last year’s race, but there was no de Palma to set his nerves on edge. The rest of the field did not have enough speed even to trail him. He won an endurance drive, not a speed contest.

Mechanical troubles held an upper hand in eliminating half of the would-be winners, with tire change delays a minor consideration. The triumphant son of Italy opened his pocket for first money for the fourth time in American a long-distance race – he won the Vanderbilt cup, the grand prize, and the Chicago speedway event in 1915 – after 300 miles of routine driving, rolling lap after lap with the consistency of a barn-bound truck horse. He stopped at the pits but once, that in the seventieth lap, when he changed the right rear tire and replenished the gasoline supply.

Resta was never headed after he took the lead from Aitken in the forty-fifth mile. At the start, Rickenbacher, in the Maxwell, pulled away from the rest of the bunch, but his spurt was short lived, as a connecting rod poked its way through the white speeder’s crankcase in the twentieth lap. From the time of Rickenbacher’s retirement until the sixtieth lap had been turned, Resta’s trailer was a see-saw between Louis Chevrolet in the new and untried Frontenac, D’Alene in his year-old Duesenberg and Johnie Aitken at the wheel of another Peugeot. Ralph Mulford carried his Peugeot into second place at 200 miles but was passed in the next ten laps by D’Alene, who held a narrow edge on this position until the finish.

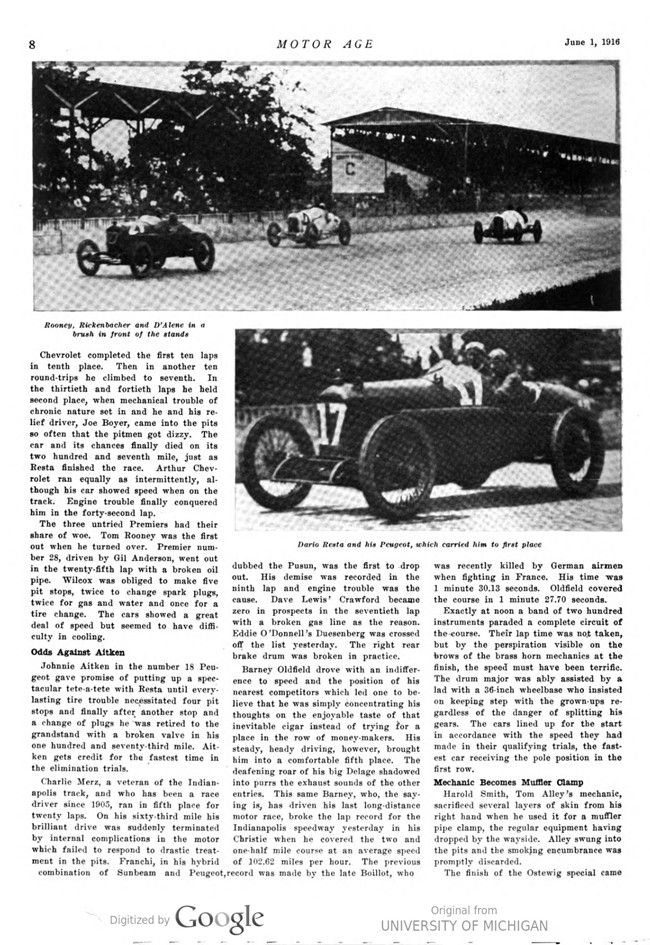

D’Alene’s Driving a Surprise

Wilbur D’Alene’s drive into second position was a surprise and a revelation. He is one of the youngsters of the racing business, and drove a car which had been worn and torn in many previous combats. He won his position in exactly the same way as did Resta, by relentless consistency. Like the winner, he stopped at the pits but once. He was docked 1 minute and 35 seconds for a right rear tire change and new supply of gas and oil.

After an exciting brush with D’Alene, which was one of the real features of the race, Ralph Mulford was outspeeded and dropped back into third position, which he held until the finish. Mulford also made but one pit stop, when he changed his right rear and took on oil and gas.

The fact that the first three cars got the checkered flag within 4 minutes of each other, made the element of chance a strong factor in the last five or ten laps. Had Resta been obliged to stop during this period, the honors probably would have gone to D’Alene or Mulford. The former’s time was 3 hours, 36 minutes, 15.28 seconds, at an average of 83.25 miles an hour, and Mulford was flagged a minute and 41 seconds later with an average figure of 82.65 miles an hour.

The race was a battle between the old and the new and at the finish there was not a question as to which was the superior. The first five finishers, Resta in the Peugeot, D’Alene in the Duesenberg, Mulford in the Peugeot, Christiaens in the Sunbeam, and Oldfield in the roaring Delage, were all had seasoned mounts which had withstood the tests of previous trying grills and had had their faults remedied. The Premiers, which were as green as the hue of their bodies, and the Frontenacs, which fresh out of the paint shop, had the speed without the stamina and the result was that their spurts were punctured by innumerable pit stops for mechanical troubles. Spark plugs were changed by the score. A total of fourteen costly stops were made for this evil alone. The Frontenacs showed an insatiable appetite for the pop-producers, the two which were entered being obliged to pull into the pits seven times for this ailment.

Next in the line of bank account builders came Rickenbacher, in the Maxwell, which Henderson nursed for the first fifty-three laps. The honors for the position should be divided equally between the two drivers. Henderson drove a remarkably consistent race without a pit stop until his more experienced teammate changed seats with him. Rickenbacher pushed the car much harder than had Henderson and the pressure was too much for the fleet white Maxwell. Three stops at the pits spread gloom over the fans who had bet on Rickenbacher to win, two for tire changes and a valuable 5 minutes and 20 seconds spent on repairing a broken oil line. The Maxwell averaged 78.35 miles an hour.

Crawford’s Slow But Sturdy

Billy Chandler’s creations, the Crawfords, slow in speed but thoroughly sturdy, took eighth and ninth, Johnson and Chandler the respective drivers. The former averaged 74.45 and the latter 74.05 miles an hour.

An $800 check for tenth place was the reward for Haebe’s steady piloting in the Ostewig special. He averaged 73.30 miles an hour. Although it was not, from a monetary consideration, as heartbreaking a defeat as de Palma sustained in 1912 when he lost the lead and position in the 500-mile classic by failure of his car in the last lap, the final circuit of Tom Alley, in his Ogren, brought a throb of sympathy from the 80,000 spectators. Running in eighth place in his two-hundred and ninety-seventh mile the diminutive builder-driver limped to the tape on one cylinder and smiled at starter Marmon and the green flag he waved. That one cylinder bore him around his last lap, but not until he had been passed by the yellow Crawfords and the stubby Ostewig of Haebe’s. The first official announcement gave Alley tenth place, but a checking of the time records after the race crowded him just out of the money.

Lecain Is Seriously Hurt

Two upsets, both from the same cause, brought serious and possible fatal injuries upon Jack Lecain, who was driving as relief in De Vigne’s Delage, and hurt Tom Rooney, who climbed the top rail in the south turn in his green Premier. Rooney’s jinx caught up with him in his forty-eighth lap. He misjudged his speed while running high on the south turn, skidded in the path of oil and bumped the outer rail with such force that his mechanic, Thane Houser, was thrown over the wall and onto the dirt level beyond. Rooney was caught under the wheel and stayed with the car as it rolled over down the bricks to the inner fence. His right shoulder was dislocated, his right leg broken and he sustained painful bruises.

Like his teammate Carl Limberg, who was killed in the recent Sheepshead Bay race, Jack Lecain, the Bostonian, skidded when high up on a turn and bumped the outer guard rail. The easterner hit the oil path on the north turn at too high a rate of speed, whirled a revolution and hit the fence, then rebounded onto the track and turned over. His mechanician escaped with minor bruises, but the driver was pinned under the wreck. His skull was scraped and the scalp cut, one leg was fractured in several places and his spine seriously injured. For a time his life was despaired of, but latest reports give him a chance for recovery.

After a blue Monday of rain and its accompanying slop and puddles, the day of memory burst forth in cloudless glory. Enough breeze crossed the course throughout the morning to dry thoroughly the track and harden up the saturated infield and parking spaces. A crowd estimated at 82,000 people was in the inclosure at the time for the start. It started coming in as soon as the gates were open and the stands were well sprinkled with spectators for the morning try-outs.

Mulford, who was permitted by the judges to postpone his try-out until Monday because of his antipathy for Sunday driving, and who was soaked out from a chance on Monday by the rain, put his car through the paces this morning.

Boyer Qualifies Frontenac

The Frontenac scheduled to be driven by Gaston Chevrolet was brought onto the course at a late hour and after several attempts the brother of Louis, the veteran, failed to round the circuit in the required time. Forthwith Joe Boyer, Detroit millionaire and Frontenac financier, took the wheel and in one lap put the red aluminum creation in the race. By a special dispensation of the officials, Louis Chevrolet, whose own Frontenac was put in the sheds in the morning with an irreparably cracked cylinder, was per- mitted to drive his brother’s car and, considering the slow speed made in the preliminaries, the showing of the car in the race was commendable.

Chevrolet completed the first ten laps in tenth place. Then in another ten roundtrips he climbed to seventh. In the thirtieth and fortieth laps he held second place, when mechanical trouble of chronic nature set in and he and his relief driver, Joe Boyer, came into the pits so often that the pitmen got dizzy. The car and its chances finally died on its two hundred and seventh mile, just as Resta finished the race. Arthur Chevrolet ran equally as intermittently, although his ear showed speed when on the track. Engine trouble finally conquered him in the forty-second lap.

The three untried Premiers had their share of woe. Tom Rooney was the first out when he turned over. Premier number 28, driven by Gil Anderson, went out in the twenty-fifth lap with a broken oil pipe. Wilcox was obliged to make five pit stops, twice to change spark plugs, twice for gas and water and once for a tire change. The cars showed a great deal of speed but seemed to have difficulty in cooling.

Odds Against Aitken

Johnnie Aitken in the number 18 Peugeot gave promise of putting up a spectacular tete-a-tete with Resta until every lasting tire trouble necessitated four pit stops and finally after another stop and a change of plugs, he was retired to the grandstand with a broken valve in his one hundred and seventy-third mile. Aitken gets credit for the fastest time in the elimination trials.

Charlie Merz, a veteran of the Indianapolis track, and who has been a race driver since 1905, ran in fifth place for twenty laps. On his sixty-third mile his brilliant drive was suddenly terminated by internal complications in the motor which failed to respond to drastic treatment in the pits. Franchi, in his hybrid combination of Sunbeam and Peugeot, dubbed the Peusun, was the first to drop out. His demise was recorded in the ninth lap and engine trouble was cause. Dave Lewis‘ Crawford became zero in prospects in the seventieth lap with a broken gas line as the reason. Eddie O’Donnell’s Duesenberg was crossed off the list yesterday. The right rear brake drum was broken in practice.

Barney Oldfield drove with an indifference to speed and the position of his nearest competitors which led one to believe that he was simply concentrating his thoughts on the enjoyable taste of that inevitable cigar instead of trying for a place in the row of money-makers. His steady, heady driving, however, brought him into a comfortable fifth place. The deafening roar of his big Delage shadowed into purrs the exhaust sounds of the other entries. This same Barney, who, the saying is, has driven his last long-distance motor race, broke the lap record for the Indianapolis speedway yesterday in his Christie when he covered the two and one-half mile course at an average speed of 102.62 miles per hour. The previous record was made by the late Boillot, who was recently killed by German airmen when fighting in France. His time was 1 minute 30.13 seconds. Oldfield covered the course in 1 minute 27.70 seconds.

Exactly at noon a band of two hundred instruments paraded a complete circuit of the course. Their lap time was not taken, but by the perspiration visible on the brows of the brass horn mechanics at the finish, the speed must have been terrific. The drum major was ably assisted by a lad with a 36-inch wheelbase who insisted on keeping step with the grown-ups regardless of the danger of splitting his gears. The cars lined up for the start in accordance with the speed they had made in their qualifying trials, the fastest car receiving the pole position in the first row.

Mechanic Becomes Muffler Clamp

Harold Smith, Tom Alley’s mechanic, sacrificed several layers of skin from his right hand when he used it for a muffler pipe clamp, the regular equipment having dropped by the wayside. Alley swung into the pits and the smoking encumbrance was promptly discarded.

The finish of the Ostewig special came very near being literally its finish. When Haebe was greeted with the checkered flag his enthusiasm overran his good judgment, and he waved both hands over his head. The car without the accustomed guidance wandered over the track in front of the grandstand like a lost sheep before the winner of tenth place took the panic out of it.

A feature of the start was the daring performance of C. L. Rouse, mechanic for Johnson, who sprawled himself out over the hood of the Crawford to fasten a hood strap and rode in this position until far around the first turn while the car was turning up a dizzy pace. He was greeted by cheers from the crowd for several laps until the event was forgotten in the excitement of the ensuing speed brushes.

Rickenbacher’s Mystery

Prior to the start of the race Rickenbacher set the crowd guessing by keeping the right front steering knuckle of his Maxwell carefully covered with a khaki coat. Sleuths put on the trail finally discovered that the hidden mystery was blower connected with a hand pump beside the mechanic’s seat designed to cool the troublesome outside tire with a current of air exuded from the blower by the efforts of his undersized mechanic, Harry Goetz. Whether Eddie feared the jeers of the drivers or had a patent application in mind is a question.

The performance of the English Sunbeam, driven by Josef Christiaens, the Belgian, was a disappointment to many. Dopesters figured him out to be a strong contender for first place, and in the race he never even put in a bid. It appeared that he had speed in reserve which he never used.

The contest did not have the thrills of previous years. De Palma’s average of 90.21 miles an hour for 300 miles and 89.84 for the 500 in the 1915 event made today’s speed showing a disappointment. It was lack of competition, not lack of a fast car, that kept Resta’s average low.

——-

Notes of the Race

The Crawfords had the words „Retard Your Spark,“ printed in big black letters on the front of the radiators as a timely hint to the crankers to perform that operation before turning over the motors. It may have saved a broken wrist, who knows?

—-

Last year Resta won $10,000 by taking second place. This year his reward for first place was $12,000, but he worked shorter hours. He received the same amount of money in proportion to the number of miles driven and the relative position in which he placed that he did last year, as the aggregate prize in 1915 was $50,000 for 500 miles against this year’s $30,000 for 300 miles.

—-

Johnnie Aitken scored a cylinder in his Peugeot in practice the day before the race. Heroic efforts were made to repair the dam- age done, but the makeshift job was the eventual cause of Aitken’s undoing. Exactly the same trouble put Louie Chevrolet’s Frontenac in the discard.

—-

The RiChard had the speed to qualify but weighed some odd 1,000 pounds too much to suit the A. A. A. regulations. The judges ruled it out before the race.

—-

The Frontenacs were frequently marooned at the pits. Possibly their color had something to do with it.

—-

Christiaen’s Sunbeam was „in the white.“ The unpainted and lengthy craft from England spat clouds of oil smoke throughout the race, much to the detriment of the riders‘ complexions.

—-

A Norfolk suit, a cane, low-cut shoes and a pair of horn-rimmed glasses accompanied by Carl Fisher, speedway owner, started a morning pedestrian inspection of the course. One of the low-cut shoes became inopportunely entangled with the electrical timing wires across the starting line of the course and the havoc wrought was appalling. The above equipment, with the exception of the Norfolk suit and shoes, abandoned the owner with exasperating efficiency and scattered a rod over the bricks. Fisher escaped from the upset with a few minor bruises.

LECAIN HAS CHANCE TO LIVE

Indianapolis, Ind., May 31 – Special telegram – Jack Lecain, who crushed under his racing car in the 300-mile race yesterday afternoon, has a fighting chance for his life, it was stated at the Methodist hospital at 9 o’clock this morning. The great vitality required of a race driver gives hope for his recovery. Doctors were undecided whether to attempt an operation.

After spending an hour with Jack Lecain, Dr. H. R. Allen said:

„I have the hope for him that comes from the fact that every race driver that ever went into the Speedway Hospital has recovered.“

Lecain’s wife and one child are at his bedside. He has a fractured skull, a broken jaw and is suffering from internal injuries.

That Tom Rooney, whose Premier turned over, also may die was indicated by Dr. Allen. Rooney has a broken thigh and shoulder and is possibly injured internally.

Photo captions. – June 1, 1916 – MOTOR AGE

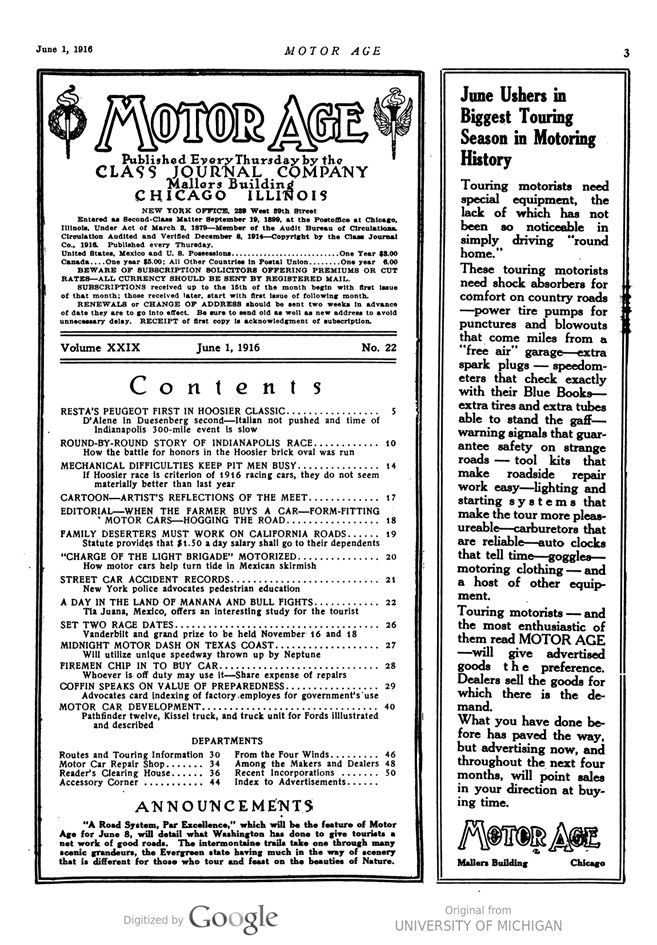

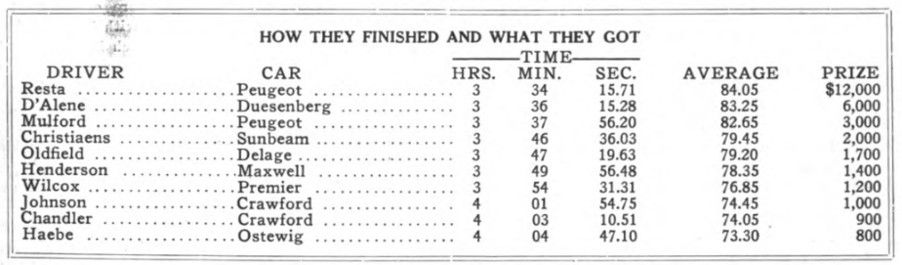

Page 5.HOW THEY FINISHED AND WHAT THEY GOT

Page 6.

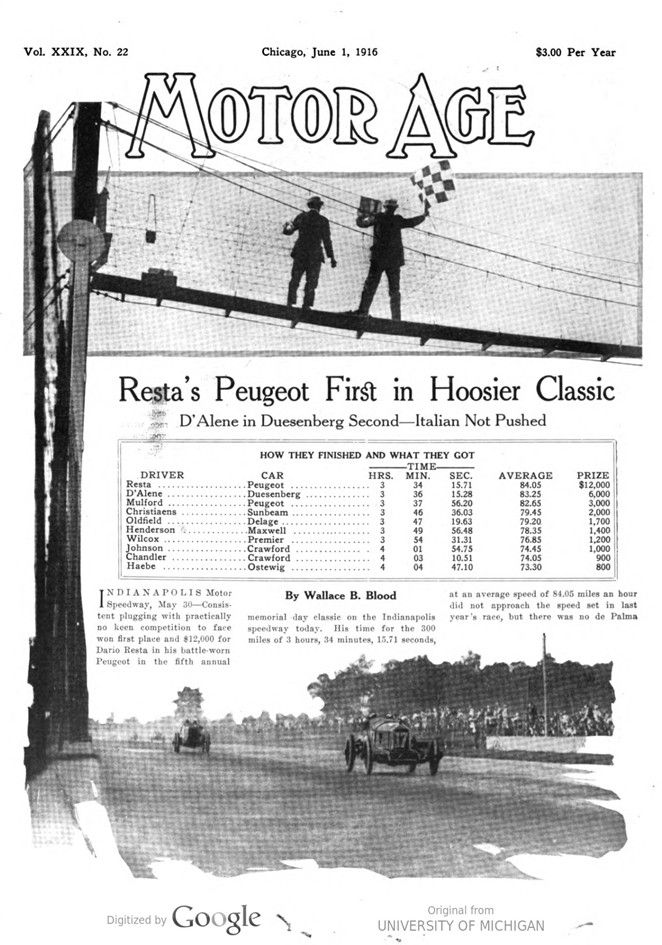

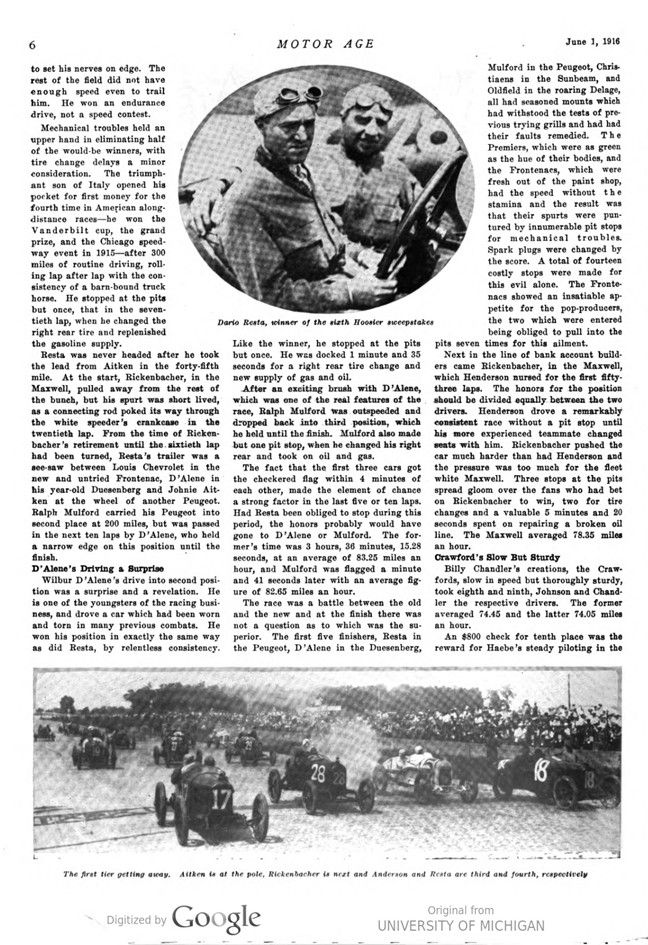

Dario Resta, winner of the sixth Hoosier sweepstakes

The first tier getting away. Aitken is at the pole, Rickenbacher is next, and Anderson and Resta are third and fourth, respectively

Page 7.

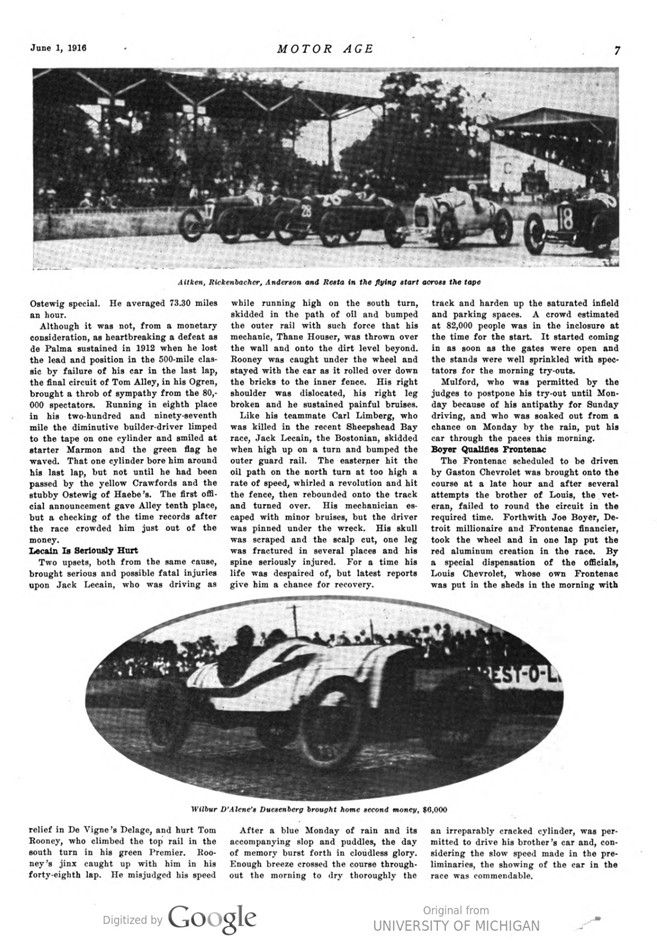

Aitken, Rickenbacher, Anderson and Resta in the flying start across the tape

Wilbur D’Alene’s Duesenberg brought home second money, $6,000

Page 8.

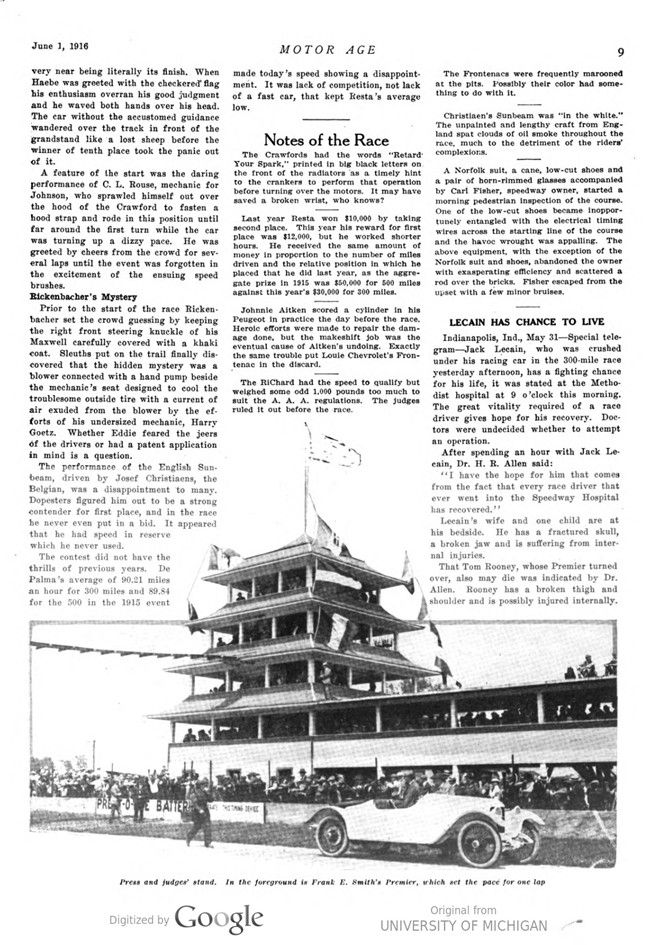

Rooney, Rickenbacher and D’Alene in a brush in front of the stands

Dario Resta and his Peugeot, which carried him to first place

Page 9.

Press and judges‘ stand. In the foreground is Frank E. Smith’s Premier, which set the pace for one lap. – PREST-O-LITE BATTERS RATE THIS TIMING DEVICE