An exciting story, how this 1906 Vanderbilt Cup Race and everything around it, took place. Although this story in all covers nine (9) pages, it is just as if You yourself would be a participant of this event; even of the night before! This really shows, that the Vanderbilt Cup Race itself and the spectators, was the event. This one is a very long read indeed, covering many, many pages of this issue, so that the risk of losing it may well be eminent. But just give it a try, read it and aftert that, you’ll wake up out of an era more than hundered years ago. But you were there on the spot!

Text and pictures with courtesy of Hathitrust.org hathitrust.org; compiled by motorracinghistory

MoToR, Vol. VI, November 1906

PAST RACES FOR THE VANDERBILT CUP.

HOW HEATH WON IN 1904, HEMERY IN 1905.

THE STORY OF AMERICA’S INTERNATIONAL ROAD RACE.

WHILE Europe, for several years, had been racing for motor-car cups and trophies, with the Bennett Trophy in the fore, America was without a Motoring Derby of its own. Track racing was our limit, with the single exception of the Ormond-Daytona Beach straightaway, a course which was adapted merely to comparatively short distances and high speed, and which was too nearly ideal to be compared with the rough-and-readiness of the average course.

Finally, the hiatus became so obvious to American motorcar sportsmen and manufacturers that when William Kissam Vanderbilt, Jr., conceived the idea of a trophy and a road race which would focus the attention of all motordom, they eagerly fell in with the idea and the „Race for the Vanderbilt Cup“ became an established institution. France, Germany, England, Italy, and Austria were the only countries, outside America, where motoring had assumed definite proportions, and the donor of the cup evidently calculated that such a trophy, in such a fertile field for commercial enterprise as America, would induce all these nations eventually to „make the try.“

In general, the conditions of the deed of gift of the Vanderbilt Cup may be summed up as follows: No more than five cars may compete from any one country; the cars which represent a country must be built in that country; the cars of any country which wins the trophy two years successively is entitled to retain the trophy and have the race contested for on its own soil under the auspices of the recognized national club, such as the Automobile Club of France, the Kaiserlicher Automobile Club of Germany, the Automobile Club of Great Britain and Ireland, etc.

A great many difficulties had to be overcome in the arrangement of not only the details of the race, but the selection of the course. At the time just prior to the first Vanderbilt Cup Race there was considerable motorphobia in the rural districts where it would be necessary that such a race be run. A course near the metropolis was really essential and the only available territory – one which favored spectacular speed and would be near a great center of population – was Long Island. The great difficulty there was that while the antipathy of the rural population to the motor-car was pretty general in all country districts, the inhabitants of Long Island were in a very acute stage of the disease. Considerable skill and diplomacy therefore had to be exercised in overcoming these unfortunate symptoms. The cure was speedily performed when the merchants and hotel proprietors in the region of the proposed course wisely determined that vast numbers of motor-car enthusiasts who would leave behind them also vast quantities of dollars. The commercial instinct therefore prevailed.

The course selected ran along the Jericho Turnpike from the neighborhood of Westbury, where the grandstand and start was, to Jericho corner, where it turned to the right, passing through Hicksville to a very ugly turn at Plainedge, where it again turned to the right, passing through Hempstead to Queens corner, and another turn to the right into the Jericho Turnpike, and to the start at Westbury. The distance of the course was approximately thirty miles, which necessitated the cars making ten circuits in order to complete the necessary three hundred miles.

The first Vanderbilt Cup Race was on October 8th, 1904. The cars finished as follows (George Heath driving a Panhard, fought a nip and tuck race with Albert Clement, Jr., in a Clement):

First – George Heath, 90 H.P. Panhard.

Second – Albert Clement, Jr., 90 H.P. Clement.

Third – Herbert Lyttle, 24 H.P. Pope-Toledo.

These cars were the only two that were permitted by the officials to finish the race, inasmuch as, after Heath and Clement had crossed the line, the crowds overran the course, effectually blocking all further racing.

Lyttle, in the little Pope-Toledo, was not the only car that was still in the running when the race was called off. Schmidt in the Packard Gray Wolf, Campbell driving the Stevens Mercedes, Frank Croker in the S. & M. Simplex, and Luttgen in the Wormser Mercedes were still going, loath to quit. The most remarkable performance of the day was that of Lyttle in the 24 H.P. stock Pope-Toledo. Of course, it was impossible for his car to have won the race, owing to sufficient horsepower, but the consistency of its running spoke well for the car.

The stimulus which this first Vanderbilt Cup Race gave to American motordom, even though the cup was won by France, more than repaid for the enormous cost of completing and carrying out the whole scheme. There was some desultory talk at the time, on account of the unfortunate accident to Arents, of „never running another motor-car race in this country,“ but common sense prevailed, and the conviction spread that an absolute amateur, in the sense of one who is inexperienced, should be forbidden to drive in such a contest.

In 1905 there was another contest. It was greater than the initial one. The number of spectators were ten-fold – so great indeed that all hotels and private houses in the neighborhood of the course were taken up for accommodations for people who wanted to „be down there overnight.“

The number of entrants from America made it necessary that an Elimination Trial should be run. Ten American cars were entered for the Vanderbilt Cup Race, and the elimination contest was run on September 23rd, 1905, over a distance of 113 miles, and a course slightly different from the Vanderbilt Cup course of the year previous. The course started this time at Mineola on the Jericho Turnpike to Jericho, where it turned to the left (the year previous the course turned to the right) and went very nearly straightaway to East Norwich, where a left turn was made through Brookville, Greenville to Bull’s Head Corner. The „Back Road“ was then followed south to a point about a mile east of Albertson Station, where a right turn took the contestants to the dangerous S turn, where Foxhall Keene came to grief. At Lakeville a sharp left turn brought the cars into the Lakeville Road running to Jericho Turnpike and thence to the starting point.

The results of the Elimination Trials were as follows:

First-50 H.P. Pope-Toledo. Driven by Dingley.

Second-90 H.P. Locomobile. Driven by Tracy.

Third-38 H.P. Royal Tourist. Driven by Jardine.

Fourth-50 H.P. Haynes. Driven by Frank Nutt.

Fifth-60 H.P. Thomas. Driven by Roberts.

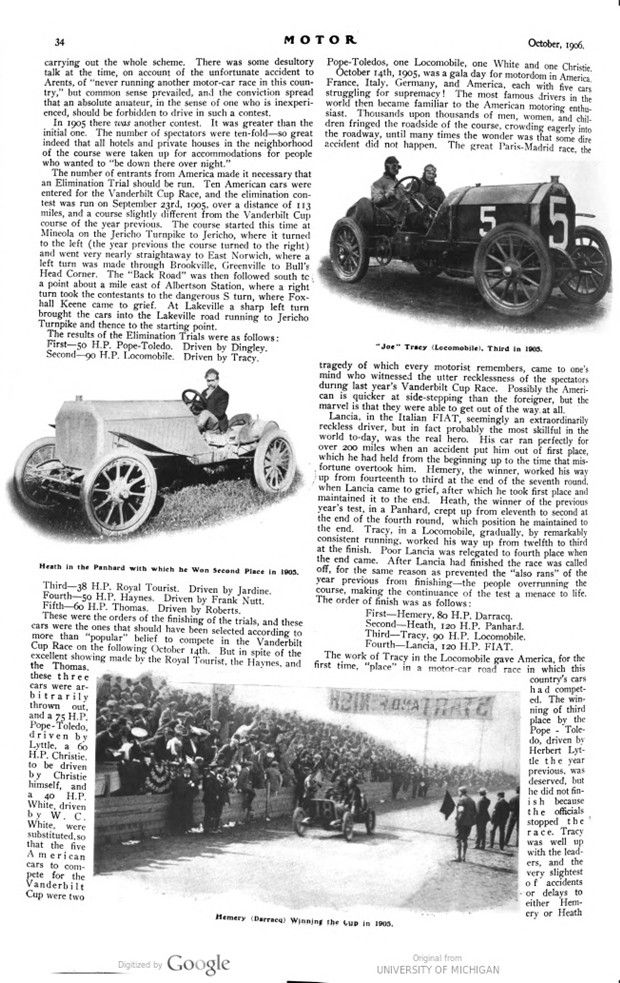

These were the orders of the finishing of the trials, and these cars were the ones that should have been selected according to more than „popular“ belief to compete in the Vanderbilt Cup Race on the following October 14th. But in spite of the excellent showing made by the Royal Tourist, the Haynes, and the Thomas, these three cars were arbitrarily thrown out, and a 75 H.P. Pope-Toledo, driven by Lyttle, a 60 H.P. Christie, to be driven by Christie himself, and a 40 H.P. White, driven by W. C. White, were substituted, so that the five American cars to compete for the Vanderbilt Cup were two Pope-Toledo’s, one Locomobile, one White and one Christie.

October 14th, 1905 was a gala day for motordom in America, France, Italy, Germany, and America, each with five cars struggling for supremacy! The most famous drivers in the world then became familiar to the American motoring enthusiast. Thousands upon thousands of men, women, and children fringed the roadside of the course, crowding eagerly into the roadway, until many times the wonder was that some dire accident did not happen. The great Paris-Madrid race, the tragedy of which every motorist remembers, came to one’s mind who witnessed the utter recklessness of the spectators during last year’s Vanderbilt Cup Race. Possibly the American is quicker at side-stepping than the foreigner, but the marvel is that they were able to get out of the way at all.

Lancia, in the Italian FIAT, seemingly an extraordinarily reckless driver, but in fact probably the most skillful in the world to-day, was the real hero. His car ran perfectly for over 200 miles when an accident put him out of first place, which he had held from the beginning up to the time that misfortune overtook him. Hemery, the winner, worked his way up from fourteenth to third at the end of the seventh round. when Lancia came to grief, after which he took first place and maintained it to the end. Heath, the winner of the previous year’s test, in a Panhard, crept up from eleventh to second at the end of the fourth round, which position he maintained to the end. Tracy, in a Locomobile, gradually, by remarkably consistent running, worked his way up from twelfth to third at the finish. Poor Lancia was relegated to fourth place when the end came. After Lancia had finished the race was called off, for the same reason as prevented the „also rans“ of the year previous from finishing-the people overrunning the course, making the continuance of the test a menace to life.

The order of finish was as follows:

First-Hemery, 80 H.P. Darracq.

Second-Heath, 120 H.P. Panhard.

Third-Tracy, 90 H.P. Locomobile.

Fourth-Lancia, 120 H.P. FIAT.

The work of Tracy in the Locomobile gave America, for the first time, „place“ in a motor-car road race in which this country’s cars had competed. The winning of third place by the Pope Toledo, driven by Herbert Lyttle the year previous, was deserved, but he did not finish because the officials stopped the race. Tracy was well up with the leaders, and the very slightest of accidents or delays to either Hemery or Heath would have given Tracy the race. But a few minutes difference in time was clocked between him and the first and second cars.

The contest of 1905 averaged over ten miles an hour faster than the contest of 1904, when Heath in a Panhard maintained an average of 52.25 miles per hour, while Hemery, in the Darracq, last year, maintained an average of 62.18 miles per hour. The probability is that, in addition to the greater ability of the 1905 cars to maintain a higher average, last year’s course was considered to be „faster“ than that of the year previous.

Lancia made the best time for a single round; his time for the fourth round was 23.18, which time was approached by none of the other contestants. Hemery’s fastest round was the fifth, 24.49. A remarkable feature of Tracy’s running was that the slowest round was only 32.53, and his fastest was 27.53.

According to the deed of gift of the Vanderbilt Cup, the race should have been run in France this year. Two years successively France, by a Panhard and a Darracq, respectively, won the Vanderbilt Cup. But the drain of supporting so many road contests in France has been so heavy that the Automobile Club of France decided that hereafter it would support but one race – the Grand Prix. From a commercial point of view, it was wise for France to refuse to take the cup. America is a big market and the splendid customer for French cars – that is way the Vanderbilt Cup Race is run in this country this year. The course is slightly different from that of last year and is as follows: The grandstand is located very nearly directly north of the Westbury Station on the Long Island Railroad. From here the course runs east along the Jericho Turnpike to Jericho, where a left turn is made along the Oyster Bay and Jericho Road to East Norwich. At this point another left turn is made into the road running through Brookville, and Greenvale to Greenvale Station. Here what is known as the Back Road is taken to Old Westbury, where the hairpin turn is located. The course then runs over the old Westbury Road through Roslyn and north to Hempstead Turnpike, which is followed into Manhasset. From here the course leads to Lakeville and then over the new Willouts Road to Searington, and then north and along to Mineola, where the Jericho Turnpike is again met and followed to the grandstand and starting point.

Again, there will be twenty cars represented, five from France, five from Italy, five from Germany, and five from America. It is fully expected that, while last year’s race was a close struggle all the way through between the first four, this year’s will be still more keenly contested, inasmuch as with confidence born of success, the American car and its advocates, declare that the Stars and Stripes will take the cup.

MOTOR – Vol. 6, October 1906. Pages 35 – 37.

GROOMING A CUP CANDIDATE.

WHAT PREPARATION FOR A BIG ROAD RACE REALLY MEANS. THE COST OF RACING-HOW CAR AND DRIVER ARE „TUNED UP“.

MOTOR road racing is a strenuous business. It is not play for children nor does it contain the elements of a pink tea. It is hard work from start to finish and requires labor of brain and muscle and tact and skill from the time when the construction of a racer is begun to the close of the race. For the association or club which promotes it, for the competitors and their manifold assistants, for the newspaper men who report it, for the photographers who picture it, for the railroad and ferry employees who get the public to the course, and even for the public itself, it means hardship, self-denial and aggressiveness. But so royal is the sport, so interesting the preliminary and actual work and so great the returns for all concerned, that cup hunters never waver in their enthusiasm.

The American Elimination Trials just completed on the Nassau County Circuit presented certain features in their preparation and execution which went to show to a remarkable degree how ornate and thorough is the work of preparing a cup racer for this appointed task. Roughly speaking, the actual contestants used upward of five hundred people to prepare the cars for the race. This does not include, in certain cases, the resources of entire factories used in putting together the great speed machines, but only the people actually employed in the direct work of grooming the steel steeds for their momentous tasks. How such an estimate is arrived at may be found in the following figures: The tire company which furnished the tires for all the contestants employed on the course fifty-two mechanics, not including the foremen and traveling representative who participated in the work of installing the tire stations. The E. R. Thomas Motor Company, which had three cars in the trials, used more than fifty people on the track. The Locomobile Company of America sent aides to the number of fifteen for Joseph Tracy, who drove the Locomobile, and the other contestants furnished help in proportion. In addition, the entire forces of the local New York agencies for practically all the cars concerned were called upon to render help, either before or during the race, and a considerable number of managers and drivers were also called upon to assist.

To estimate the actual expenses of building and placing cars and providing drivers in the contest is a task which is simply an impossibility. But it is safe to say that the total expenses for each car which started averaged at least $20,000. In some cases, the expenses per car were much heavier than this, but these were offset by the comparatively economical methods of some of the contestants who took chances on the number of their assistants, and in some cases suffered thereby. To get away from the actual contest expenses for less than $15,000 was a notable exception to the rule.

It must be borne in mind that this does not take in account the money spent for advertising or spent by heads of concerns in visits to the course, or stops upon it, nor the tremendous expense connected with the race, including the erection of stations, the oiling and wiring of the track, the expenses of timing, judging and reporting the race, and manifold other details of cost. All in all, even the American Elimination Trials moved several millions of dollars from hand to hand, and it is safe to say that the same expenditure will be made necessary in connection with the Vanderbilt Race proper.

The beginning of cup race construction dates back for periods, ranging from three months to a year before the actual date of the race. It is known that in some instances the plans for the racing machines were drawn as long ago as last October, and draftsmen were busy for months working out the details of these plans. Actual construction from the raw material began in all cases at least six months prior to the race. And in the case of the Pope Manufacturing Company, it must have been begun much earlier because it had its car running four months before the date of the trial. All the manufacturers had their cars on wheels and driving at least a month before the date of the trials. This constructive work was undertaken at a time when the manufacturers were very busy with their regular summer output, in many cases weeks be- hind their orders, and hence the services of mechanics and foremen and constructors, and designers, were had at double value. Nor can any workman who participates in the construction of a racing machine be a cheap or low-priced man.

All around, the workmen must be the best the market affords, a pick of the factory in their various lines of endeavor.

Thus, it is that the remarkable results, both as to speed and quality of workmanship were achieved, and these results were more remarkable this year than ever before. The contesting cars in the 1906 Elimination Trials were more distinctly racing machines and overcame more exigencies and drawbacks than ever before. In other words, these machines in the main were more nearly the ideal motor racing car than has ever before been the case.

For periods ranging from two weeks to two months the scene of activity is shifted to the lines of the cup course or the country immediately adjoining it. Some manufacturers preferred the installing of their camps a long time before the date of the race in order to allow their drivers to thoroughly test out the machines on the spot and to study, in all its details and intricacies, the road over which they were to travel; while others pursued the principle of testing their cars at distant points and sending them to the cup course and vicinity at as late a date as possible commensurate with a complete knowledge of the contest by the driver and a thorough study of the car.

Heretofore it has been the custom in preparing for races to rent out-buildings connected with road houses or private estates for cup race camps. This year, however, a tendency was shown to erect special garages and equip these in a manner especially designed for the work to be undertaken. The Locomobile Company built a large shed in the grounds of the Lakeville Hotel for this purpose and fenced off a large-sized plot of ground with high wire fencing, the space inside being used entirely for cup race purposes. The Maxwell-Briscoe Motor Company leased a number of acres on the Jericho Turnpike and erected thereon a temporary garage 40 x 80 feet, as its storeroom and repair shop. Walter Christie, always an enthusiast, and very conscientious in this preliminary work, also erected a wooden garage, well equipped, but of smaller dimensions, on the turnpike joining a crossroad which gave him a superior chance. The Old Motor Works located near Westbury on a road about three-quarters of a mile from the course, and there built a concrete garage, fitted out with considerable machinery and numbers of tools, and provided for Keeler, its driver, and his many assistants, in a remarkable and thorough manner. Others of the contestants used buildings already erected, but the amount of refitting necessary in a number of cases made the cost almost as expensive as if they had built outright.

The place and space secured, it was then a question how much of an equipment would be necessary. In some regards the installations this year have been more elaborate than ever before. Lathes, milling machines, presses, drills, shaving machines, even automatic nut and bolt machines have been set up, and power plants to run them have been installed. Hand tools in endless profusion have been sent from the factories, forges have been erected, compressed air machines have been put in, and in nearly every detail of construction the training camps have been made miniature copies of the factories. After this enormous amount of machinery and details have been installed, there goes with it the necessity of providing able mechanics to operate it. As a result, the quota of factory hands sent to the course this year has been remarkable in its extent and in the technical character of the people employed. The best technical portion of the factories has been put on the work.

But after all this work on the racer has been done, there still remains the actual testing and „tuning up“ of the cars by the drivers and their assistants, and the detailed study of the course in all its turns and curves and grades and windings before a fair chance at successful competition is possible. At this point, if not before, the cup drivers‘ word becomes law. He assumes complete control of the plant, the assistants, and the car. He dictates how much work shall be done and when and where and the hours when he will pursue certain lines of road effort, the help he will have with him on the road, even the hours at which the assistants are to go to bed, when they are to eat, and all other details, in-so-far as he cared to assume them. It is suicidal to cross the driver at any stage of the game. If any word is disputed, he will throw back the responsibility of any defeat upon the man who is responsible for the order. This situation was modified somewhat in cases where some representative of the concern gave orders instead of the driver, but the effect was the same. Without the hand of iron guiding the course of the preparations there could be no chance of success.

The term „tuning up“ on a cup race is not generally understood by the public. What is meant is that the driver gets the „feel“ of the car. He studies the action of the cylinders and principally the ignition of the car and learns familiarly how to regulate the mixture of the gas, and how to handle the speed levers or pedals, how far to throw in his clutch and numberless other points about his car which are alike in no two racers, not even when built as twins or triplets, and supposed to be identical in every particular. For it must be understood that there is a certain individuality about every motor car, as about every person. No matter what the specifications, each motor has a distinct action and is subject to vagaries as is a human machine. These vagaries must be humored or beaten into submission, and the driver must know in every detail just what action will result from each separate act on his part in the handling of the car.

The next step is to learn the course in all its many details, and following this the action of the car on the course must be studied. The same car cannot be driven in the same way on two different courses, and it is necessary to find out just what the car will do under certain climatic and geographical conditions. Even then there is a tremendous amount of risk and chance about the driving of the car. All theory and experience which comes from driving cars at ordinary tour speed are thrown away in the study of racing. The action on the engine, the action on the tires, the balance of the car, these needs are essentially different when racing is going forward than they are under normal conditions. And the driver must learn what the new conditions are and suit his management of the car to them.

Scarcely any car goes to the racecourse under the conditions which will prevail at the time of the race. Trials will prove that this wiring is wrong or that battery is badly placed, or that this screw is likely to work loose and a new method of fastening it must be devised, or that gasoline or oil tank is badly placed, and will de damaged and rendered useless by the action of the chassis, or the wheels are weak, or the oiling system is not adequate, or the spark plugs are not of the right adjustment or make, or the tires are not properly set or of the right size, or bumpers are necessary, or the seat is too high or too low, or the hand pumps are not handily placed, or the steering wheel is not properly reinforced, or needs wrapping, or a thousand other details are susceptible of change or improvement. Every little part and accessory of the car has to be studied separately by the driver, and such improvements and changes made from time to time as will give it greater flexibility or strength or adaptability. And it is one continuous long study followed by work, unceasing work, to present the car with a fair prospect of success at the starting line on the race day. All this and more is included in the term „tuning up.“ It is a comprehensive term and may be said to indicate all the work in-so-far as the car itself is concerned. And then, perhaps, for one poor lap or a limited number of laps the car may answer to all the work and thought and care which has been put upon it, and break down in some un- heard-, unthought-of spot or manner.

Eternal vigilance is the price of cup racing. A study of the preparation of racers in our great road races goes to show that it is this detailed judgment and labor which make for the improvement of motor-car construction generally.

Study the history of the cup racing car from its advance into the factory as raw material to its appearance at the grandstand at six o’clock on the morning of the trial day and you have the whole secret of why great road races have resulted in the manifold improvement of the motor-car as a pulsating, moving, useful aid to mankind. That road racing has resulted in the constant improvement of cars for everyday use cannot be denied. The whole problem of motor-car construction- the combining of lightness, durability and speed-is involved in the construction of a racer.

Photo captions.

Page 33. 7 – Heath (Panhard), the Winner in 1904. / 12 – Clement (Clement). Who Finished Second in 1904. / 6 – Lyttle (Pope-Toledo). Third, 1904.

Page 34. 11 – Heath in the Panhard with which he Won Second Place in 1905. / 5 – „Joe“ Tracy (Locomobile), Third in 1905. / Hemery (Darracq) Winning the Cup in 1905.

Page 35. Photo by Lazarnick. A Glimpse of the Locomobile Training Quarters.

Page 36. Photo by Lazarnick. The Apperson Headquarters at the Old „s“ Turn.

Practicing on the Course. – Interior of Pope-Toledo Quarters.

Page 37. Photos by Spooner & Wells. „Tuning Up“ on the Course-the Three Frayer-Millers at Jericho Corner.

Interested Natives. – Where the Oldsmobile was “Groomed.“ – Christie’s Quarters.