In 1919, an apparently new magazine appeared, Automotive Industries, which was in fact the successor of The Automobile.

This article of the 5 June 1919 issue, following the main one, describes significant technical features of the participating cars.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRIES (THE AUTOMOBILE) – Vol. XL, No. 23, June 5, 1919

Mechanical Notes from the Race

One of the best reasons for racing is that it enables us to determine the weakestlinks in the chain of car components and by this knowledge to profit in the design and construction of vehicles intended for passenger or commercial purposes. The mortality among racing cars is always so high under the severe stresses which they are compelled to stand that the conclusion of a race brings to light a total list of minor and major troubles which often indicate to the designer what it is permissible to do in ordinary construction.

Furthermore, from a theoretical standpoint there is much to be learned in regard to what can be done in the handling of gases at high velocity and what is the limit in allowable piston speeds. Little or no problems of carburetion are, as a rule, apparent, but there is always much to learn in manifold design and, particularly, weak spots in the cooling system are brought to light by the failure of spark plugs and often through the tendency to overheat, as indicated by excessive steaming, etc.

The major number of stops at the pits was directly due to tire failure. This would be expected, as the race was run under a burning sun on a track which was already superheated by two days of exceedingly hot weather which preceded the start of the classic. Sixty-seven tire changes were made. Of this number thirty-one, or nearly 50 per cent, were right rears, which is the usual percentage for the Indianapolis track. Fifteen were left rears, twelve left fronts, and nine right fronts. It would be wrong to assume from these figures that tire performance has not improved. In the first place, probably 30 per cent of the tires were changed before it became necessary, because the cars were drawn up to the pits for other purposes, affording the opportunity to make the replacement. Secondly, the conditions as far as heat and direct sunlight were concerned were never equaled at an Indianapolis race. During practically the entire period the track was in the direct glare of the sun, with no sheltering clouds in sight.

Three cars changed tires six times, these being De Palma’s Packard, the Hudson Special driven by Haibe, and the Ballot driven by Guyot. Three cars changed five times; two changed four times; three changed three times and the remainder changed at least once. No car went for the entire distance without a change.

The winner made only one stop, at which time he took on a complete set of tires as well as oil, gas and water, and he also tightened his shock absorbers. Disregarding this stop, it was the steady running program of Wilcox which won. De Palma and Louis Chevrolet, who proved in the early part of the race that they were the most dangerous contenders as far as actual speed was concerned, had to make stops for failure in vital parts. De Palma had to make adjustments on his valve drive mechanism during his first stop, and on his second stop had to replace an entire front right wheel bearing assembly. This took such a long time that it put him out of the running so far as first place was concerned. While the car was on the track, however, its steady, fast running made it the pace maker, and had it not been for these two mechanical mishaps, De Palma probably would have been the winner. At the 100-mile and 200-mile marks he was in the lead, having broken the speedway record for these distances.

The failure of the Frontenacs showed that they were too lightly built to withstand the stresses imposed by the Indianapolis track. In fact, dangerous weakness was apparent on the rear axle drums. Before the race, on the brake test, the drum on Louis Chevrolet’s car cracked under the strain imposed by bringing the car to a stop. This break became apparent immediately after the brake was applied. It was on the left rear drum carrier. The right rear drum on the same car broke during the race.

The front axle was also too light, at least the steering knuckle spindle. This became crystallized, due to the continuous bouncing over the rough track, and when the car was on the turn entering the home stretch it broke off, throwing the wheel over the fence, and it was only by the most skillful driving that Chevrolet was able to bring the Frontenac to a halt before his pit on three wheels.

Twice during the race this three-wheel performance was necessitated by failures of the front and rear axles on these cars. The rear axle failures were evidently due to the fact that the aluminum employed was not strong enough to endure the torsional strains resulting from the tremendous acceleration upon leaving the curves.

The Indianapolis track is banked for 90 m.p.h., which makes it distinctly a drivers‘ track and allows the human element to enter in the management of a car on the turns to a far greater extent than on the 120 m.p.h. New York Speedway. For this reason spark plug troubles are always more apparent on this track, due to the fact that it is necessary to shut off on the turns, allowing the oiling systems a chance to load up before the throttle is again opened. Puffs of smoke are always apparent at the entrances to the back and home stretches, due to the use of the accelerator in gaining speed for the straightaways. It is not surprising that there were twelve stops for spark plugs, during some of which the whole set of plugs was renewed.

The Ballot cars proved a disappointment. While steady, they either did not possess the necessary speed to bring them into prominent position, or else the drivers did not take the same chances on the curves as the others.

The Sunbeams were withdrawn just before the race, and a rumor went around that this was due to the fact that their cylinder displacement was 304 cu. in. and thus beyond the set limit. Investigation has about disproved this, and it is now stated that Resta, in a test drive, found that at 2500 r.p.m. of the engine there was a critical speed at which vibration was so severe that it would have been impossible for the cars to withstand a 500-mile grind. The cars are to be shipped back to England.

There is no doubt that the rough track greatly bothered the Ballot drivers. These cars may show higher speeds in future events than they did at Indianapolis, as there was a feeling before and during the race that they were being held back.

Engineering opinion is growing that 300 cu. in. is too high a limit for cars for the Indianapolis track: it is felt that the limit should be materially reduced in order that racing may be of the greatest possible benefit to the designer. Under present conditions, the cars are so much faster than the drivers (to use a track expression), particularly on tracks like the Indianapolis, that most of the value of the race is lost.

The Duesenberg 4-cylinder, 16-valve engine of 334-in. bore by 64-in. stroke, was used by O’Donnell (Duesenberg), Hitke (Roamer Special) LeCocq (Roamer Special), Thurman (Thurman Special), and D’Alene (Duesenberg-Shannon Special). These cars showed sufficient speed to put them well up in the race, but owing to the inexperience of their drivers, two of the cars were involved in fatal accidents.

A careful study of the race makes it very apparent that practically all of the cars were much faster than the drivers, which is to say that the cars were capable of developing a speed beyond the limit at which their drivers could safely handle them. This is particularly true in those cases where the drivers had had little or no experience in track racing. The Ballot cars may show up better in races on speedways which are banked for a speed of 120 m.p.h. The drivers on the Ballot cars were also too much exposed to the wind pressure. This should be corrected and the seating arrangement should be so changed that the drivers may occupy a more lax position than was possible in the Indianapolis race, where they were notably tense and not at all at ease.

Car Characteristics

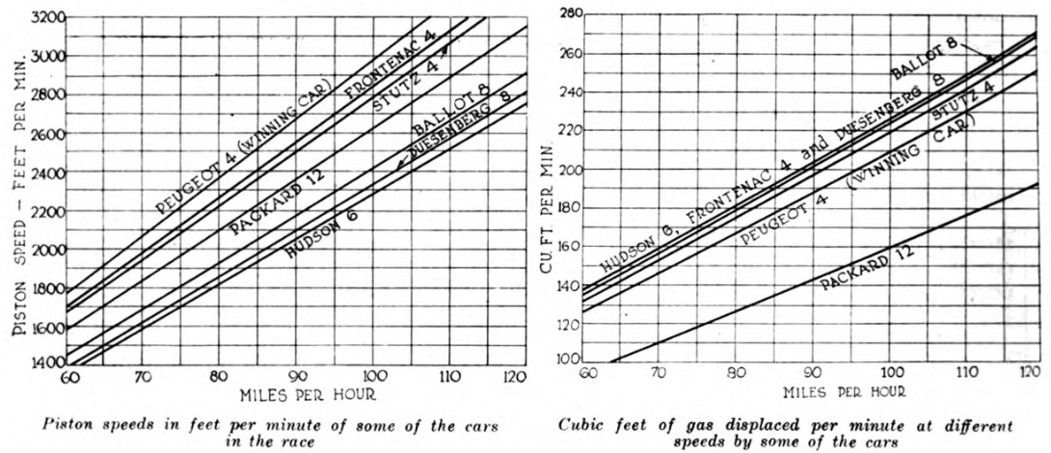

Widely differing characteristics were possessed by the cars entering the race. An analysis shows that the winning Peugeot had the highest piston speed of any of the cars. At 87.9 m.p.h., the average speed maintained by the Peugeot in winning the race, the piston speed was 2620 ft. per min., or about 600 ft. per min. more than that of the Hudson, which had about the lowest piston speed of any of the cars in the race. The accompanying chart gives graphically the piston speeds of the typical cars in the race and it will be noticed that the winning Peugeot was considerably faster as regards piston velocity for a given car speed than the other cars.

Considering gas velocities, in the absence of complete statistics on valve areas, these may be plotted on a basis of cubic inches of gas displaced at definite speeds. It is interesting to note that outside of the twelve-cylinder Packard, the winning Peugeot had a lower displacement per minute at any given speed than the other types. This is in spite of the fact that its piston velocity was the highest and is due to the dimensions of the Peugeots, which have a piston displacement of 287 cu. in., as com- pared with the others, which are close to the 300 mark. The only small displacement car in the race was 150 cu. in., this being the Baby Peugeot with a 2.15 15/16 x 5½ in. engine.

The 12-Cylinder Packard

The Packard 12-cylinder car, which, from its performance on the first 100 miles of the race, was probably as fast as any car on the track, if not the fastest, has only a 4½ in. stroke. Thus, although turning at sufficient speed to give it an intermediate position as far as piston speed is concerned, its position is low on a gas volume basis, and the car probably would show up notably from an economy standpoint were it possible to secure accurate records. Unfortunately, this is not the case, owing to the impossibility of measuring the fuel remaining in the tanks at the conclusion of the race or of measuring the amount put in during the race because of the quantity spilled.

From close observations it appears that the 500 miles were run by the winner on 45 gal, of gasoline. This would give an average of approximately 11 miles to the gallon, showing a high thermal efficiency, as would be expected under conditions of practically wide-open throttle at high speed.

The spark plug troubles were due to fouling more than to fusing, as only little of the latter was seen. The fouling trouble is no doubt the result of the oil-loading due to the acceleration on the turns, as previously pointed out. The only car which showed symptoms of plug fusing due to overheating was car 19, Hudson Special. This car had to change plugs four times and took on water six times, showing that it was badly troubled with overheating. On this same car a sticking valve gave a great amount of trouble.

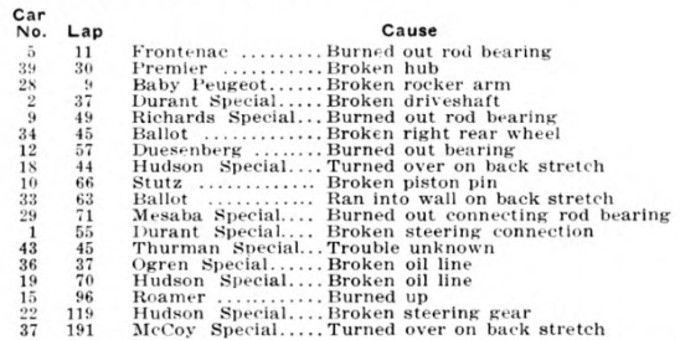

In studying the reasons which eliminated the different cars, the fact becomes apparent that more failures were due to drivers not experienced on the Indianapolis track than to any imperfection in the cars themselves, although such defects showed up in some instances. The list of eliminations is as follows:

(see table with Car No’s, Laps and Failure causes)

While it is almost impossible to tell the cause of accidents such as those which marred Saturday’s race, it is certain that in practically every case the lack of experience was one of the main factors.

Minor Troubles Cause Delays

As in all long-distance races, minor troubles were responsible for a great many delays. For instance, one of the Peugeots had to come into the pit twelve times owing to oiling troubles. This car could not hold its pressure and had to draw up to the pit to have the oil pump manipulated at frequent intervals. Trouble of this kind can, of course, be readily avoided if it is foreseen. The same applies to the Detroit Special, which had leaky water connections.

It is quite apparent that Ralph De Palma and Louis Chevrolet would have been further up in front toward the end and would probably have given each other and the winners a breathless contest for first honors if they had dodged their troubles. In fact, both of these drivers made major repairs on their cars during the race and yet finished well up in the money. Louis Chevrolet had to stop seven times. These cars did not possess sufficiently strong axles to withstand the great acceleration made possible by the powerful engines. A broken steering knuckle on one of the cars, a broken right rear hub on another, and a left rear wheel coming off, and a third, because of failure of the aluminum shell construction in the rear axle, tell the story of the Frontenac in the race. It was only by exceptional driving that the Cheyrolets were able to finish with two of their Frontenac cars.

Photo captions.

Page 1204.June 5, 1919 AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRIES THE AUTOMOBILE.

Piston speeds in feet per minute of some of the cars in the race

PISTON SPEED – FEET MIN. PER MIN. — MILES PER HOUR: PEUGEOT 4 (WINNING CAR) FRONTENAC 4 STUTZ 4 PACKARD 12 BALLOT 8 DUESENBERG 8 HUDSON 6

Cubic feet of gas displaced per minute at different speeds by some of the cars

CU. FT. PER MIN — MILES PER HOUR: HUDSON 6, FRONTENAC 4 and DUESENBERG 8 BALLOT 8. STUTZ 4 PEUGEOT 4 (WINNING CAR) PACKARD 12

Airplane view of the speedway

Page 1205.

As usual, the start was a flying one, J. G. Vincent and Eddie Rickenbacker pacing the pack for a lap and then drawing to one side. This is the end of the paced lap.

Page 1206.

Cars bunched at the southeast turn

Drivers and Specifications of Cars, with Their Equipment (Table)

Page 1207.

Wilcox, the winner receiving congratulations

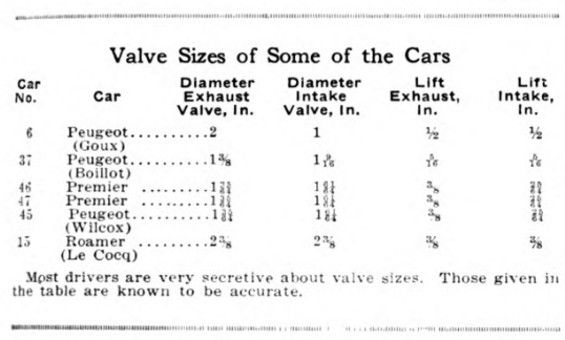

Valve Sizes of Some of the Cars

(Most drivers are very secretive about valve sizes. Those given in the table are known to be accurate.)