Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

MOTOR AGE Vol. XXVII, No. 22 Chicago, June 3, 1915 $3.00 Per Year

Mechanical Lessons Taught in Record-Breaking Contest

300-Inch Motors Show Speed and Stamina in American Debut

By Darwin S. Hatch

INDIANAPOLIS, IND., May 31. – That engine sizes can be reduced materially without causing loss in speed or stamina was demonstrated most forcibly today when four cars averaging a third less in cylinder volume than those of a year ago finished the 500-mile grind on the brick oval at a speed better than that of the winner of the 1914 event. The reduction of the allowable piston displacement from 450 inches as it was last year, to the 300-cubic inch limit of today’s race, brought out a half-dozen brand new cars designed for the increased efficiency made necessary by the lower limit of size and also forced improvement in several older ones which were already un- der the limit of cylinder volume.

The two most notable of the latter are de Palma’s Mercedes and Resta’s Peugeot, both of which showed surprising improvement in performance as compared with that in Europe last season. Nearly all the American cars under 300 inches were new productions, built expressly for this race, and their showing is remarkable when it is taken into consideration that today’s event is the debut for the most of them.

Showing of New Cars Surprising

It was to be expected that more or less trouble of a mechanical nature would be experienced during the race in view of the newness of the designs and the fact that the cars were untried in the actual warfare of speed, the preliminary skirmishes of practice not having been sufficiently strenuous really to try their mettle. Those who forecast an extraordinary amount of trouble from this source, however, were proven bad prophets, for the total number of stops at the pit for supplies and tires and mechanical adjustments and repairs this year does not equal that of the 1914 race. True, there were more starters last year than there were today, but the reduction in starters this year is not in proportion to the lessening of pit work.

It is not only by amazing speed and whirlwind driving that cars and their pilots gain coveted prizes; it is at the pits that a great race is won or lost; it was as much due to the stamina and comparative freedom from mechanical difficulties and tire troubles of the cars which permitted them to keep on running mile after mile without the loss of precious minutes at the supply pits.

It is worthy of note that the first five cars to receive the checkered flag at the finish today made the distance of 500 miles without ever having hood straps unbuckled, and of the ten to come in the prize money there were six cars upon which the hood was never lifted. In this roll of honor were de Palma’s Mercedes, Resta’s Peugeot, Anderson’s and Cooper’s twin Stutzes, and O’Donnell’s and Alley’s twin Duesenbergs. Alley also has the distinction of being the only driver to finish in the money on his original set of tires, although the Emden also completed the 500 miles on the tires with which it started, but not within the prize money.

By the twenty-four starters there were 102 stops, an average of four stops per car. By the eleven finishers there were forty-five stops, likewise an average of four.

The 500-mile race at Indianapolis has proved another triumph for the overhead-valve motor. This is not only because the two foreign cars which finished first and second had engines of the valve-in-the-head type, but because the excellent team performance of the three Stutz cars is direct evidence of the power of their motors. The performance of the Stutz team is probably the finest ever accomplished by a manufacturer making his debut with a totally new type of engine. It is a better performance than any British team has yet put up with an overhead-valve racing car and it has been excelled only by the showing of the Mercedes team in the French grand prix last year.

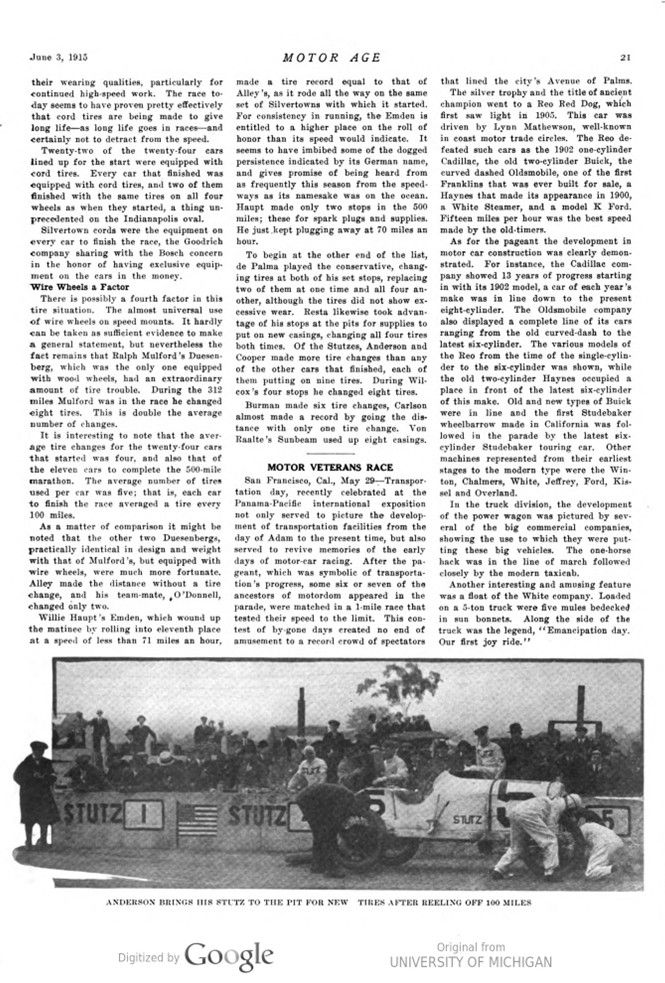

Most remarkable of all perhaps is that Wilcox’s car, with a broken valve spring, contrived to run for hours without losing a great deal of speed and to finish in so good a place. The Stutz showing can only be regarded as the greatest possible encouragement to American manufacturers; it is even more so than would have been a Stutz win with only one car of the team left in the running. The enormous importance of team performances from the viewpoint of showing the quality of design and construction is seldom realized, but actually a good team finish may be regarded as proof of a new car, while a win for a new type may have a deal of dependence upon luck. To all three of the Stutz cars throughout the race, only two mechanical mishaps occurred, one being the breaking of a valve spring, already mentioned, and the other the loosening of an exhaust pipe on the same car. No work whatever was done to either of the three cars save the necessary changing of tires and refilling with gasoline.

Stutz Showing Most Creditable

From the Stutz motors there is probably little to be learned fundamentally. They are merely up-to-date designs carried out with good material and the best of workmanship. It is a splendid testimony to what an American manufacturer can do when he is prepared to give much time and money to developing racing cars.

Seeing that this is the first time the sixteen-valve racing motor has been really tried out in this country as a team design, the degree of success attained is remarkable.

The Winners

The two winning cars, Resta’s Peugeot and de Palma’s Mercedes, have met before and the last occasion in France showed that there was little to choose between them. In the Indianapolis race, if Resta had not had trouble with his steering gear, there is no doubt he could have made a little better time and the race would perhaps have been won at just over, instead of just under, 90 miles an hour. About 200 miles from the finish, Resta found a great deal of slack in the steering, making it difficult to negotiate the turns as fast as they can be taken normally. Examination showed the trouble to be in the worm gear itself and at the finish there was about 4 inches free movement on the rim of the wheel.

Both de Palma and Resta ran right through without ever lifting the hood and both had only two stops at the pits, taking on tires and gasoline. De Palma took some oil, but Resta did not even do this. It seems that de Palma was extremely lucky to be able to finish a winner, as a connecting-rod broke and punched two holes through the crankcase two laps from the finish. Only good fortune prevented a repetition of his unlucky experience of 2 years ago.

Thus it looks as though both first and second man had reason to thank good fortune for their positions, since Resta could not have continued very much longer with the steering gear in so loose a condition. Resta was driving with caution on this account.

As a commentary upon the performance of these two cars the most striking thing is that they both seem better than they were a year ago. Usually a year-old car is not up to its original form. The reason is that just as much care has been taken in preparing these cars as would be given to making new ones; also it is thought that the Packard carbureter of the Mercedes is much better suited to American gasoline than the foreign carbureters found on most imported racing cars.

It is a fact that the Mercedes throttles down much better now than with the old instrument and there is little or no popping in the intake pipe when cutting out for a turn. De Palma says the car is 4 seconds faster per lap with the new carbureter. This is the first important race for a long time that has been won by a car with a carbureter containing an air valve.

Turning to the adventures of the other Peugeots, of which the small one in Bab- cock’s hands went out of business on the far side of the track, after 290 miles, with a cracked cylinder. Babcock had made one stop only for a rear tire and up to his retirement seemed to be going well. Bur- man had a curious experience; a sudden noise of most alarming but intermittent character; Burman said he thought the whole engine was about to break up and that the sounds were most likely due to some fault in the lubrication. He suffered two mechanical troubles, causing stops.

Perils of Peugeots

After running nearly 3 hours the gear case cover came loose and he stopped to get fixed, but this was far from serious, as the job was done in 30 seconds while the pit attendants changed some tires. After 4 hours running he had to stop again to change spark plugs and finally the copper pipe which takes oil to the camshaft broke and had to be bound up with a length of rubber hose. This happened at 4½ hours from the start. Here failure of the pipe is traceable to workmanship; probably, it had not been annealed lately and copper pipes on racing cars, which are subject to severe shocks, soon become brittle. In fact, a pipe, which is quite soft at the start of a 500-mile race, can, and often does, become as brittle as glass by the end of the race.

Other Foreigners Underpowered

The other foreigners were the Bugatti and the Sunbeams and, of these, only the two English-owned cars were new enough to hope for a win. The Bugatti was obviously underpowered for a race of this caliber and the same is true of Grant’s car, which was a fine machine when it was new. Porporato, who looked like standing well up amongst the. leaders, suffered the misfortune to freeze a piston after running 425 miles. This probably was due to a broken piston ring, but it will need internal investigation to make sure.

He also suffered a stop to fix his straps for holding down the hood after running 1½ hours and another for the same reason 3 hours later. These cost 3 minutes 45 seconds together, which is equivalent to enough to make a two-place difference in the position on the scoring board. Porporato’s partner, Von Raalte – or Graham – lost his hood altogether after running 300 miles and was stopped in order that the referee should instruct him to pick it up and replace it, which cost a lot of time. Previously he had a 3-minute stop to change spark plugs. His most serious trouble was very peculiar, however. The platform which carries the magneto on these Sunbeams apparently is bolted securely to the side of the crankcase but is a separate piece. After running 415 miles, this worked loose and caused a stop of 16 minutes. The ignition apparatus worked loose again an hour later, taking 19 minutes to fix on this occasion. Altogether, Von Raalte lost nearly an hour at the pits, the magneto trouble being the most serious. It is a remarkable fact that the Sunbeams in European races for the last 2 years have suffered stops for curious little details like this and it is certainly not due to unpreparedness. It seems much more like bad luck.

Duesenberg Motors Show

Duesenberg motors made a showing in the race. These cars as a team of five or a team of three did well and it is to be noted that their numerous troubles were mostly unconnected with the motor. Klein had an almost unique mishap in that his gasoline and oil became mixed by the failure of the partition dividing them. This made it impossible to lubricate the motor in the way intended, namely, by pumping small charges into the crankcase. Instead, oil and gasoline were poured into both tanks indiscriminately -a ala two-cycle practice – and the crankcase filled to overflow with oil. The result was that the motor smoked so excessively that the car became a menace to the others, and was ruled out on this account after running over 5 hours. Klein had some trouble with a pump gland that leaked persistently and caused increasingly frequent stops for water right up to the time of retirement.

The Sebring had persistent spark plug trouble, losing no less than 42 minutes on this score alone, while it had another stop to fix the accelerator pedal. On his 387th mile, Cooper skidded into the safety wall, which has been erected on the inside of the curve and smashed a wheel.

Of the Duesenberg cars, the one driven by Alley suffered no troubles of a mechanical nature beyond a loosened exhaust pipe and finished the race in good shape. O’Donnell stopped only three times, and his mechanical adjustments consisted merely of the replacement of a nut which had jarred off the brake bracket, and a quick adjustment of a shock absorber.

Failure of spark plugs to stand up to the demand upon them was a recurring trouble of Rickenbacher’s sixteen-valve Maxwell and the Sebring. Examination of the plugs, which gave trouble almost as soon as they were put in, suggested that they were suffering from overheating. The most usual sort of failure consisted of a clean break across the insulation just within the steel plug body which naturally would be the hottest part. It is worthy of comment that this consumption of spark plugs was the principal trouble in England and France last year, but it was overcome before the races in most instances. Better cooling arrangements seems the easy answer and that is none too easy. The Maxwell ran well for over a couple of hours without the plug trouble setting in seriously, though there was a short stop 14 hours after the start for a clutch adjustment. After running 3½ hours the car was taken out on account of a broken connecting rod which went through the crankcase.

Maxwell Has Low Pit Record

No. 19, driven by Carlson, had the distinction of being the only car amongst the finishers to stop once only. It was also the only Maxwell that escaped trouble, since Orr’s mount was put out near the end by breaking the bearings in one of the rear wheels. First, the bearings went and this left the wheel dependent upon the withdrawable drive shaft, so the resulting tangle was utterly hopeless. This is a most unusual sort of failure and really reflects no discredit upon the Maxwell engineers. Orr had one short stop to examine plugs but did not change any. Thus, it seems that the two-valve Maxwell had no ignition trouble while the one with four valves per cylinder consumed plugs nearly as fast as they were put in. This is proof positive of the higher mean effective pressure and correspondingly higher temperature obtainable with the four-valve type of motor and it is to be expected that the way out of the difficulty will be found before the latest Maxwell racer appears again upon a speedway.

Of the remaining cars, the only one to finish was the Emden, which ran a slow but steady race and came in last of all, in eleventh place. It had only two stops, one soon after the start to change all four plugs and another at about half distance for water, gas and oil. This car likewise had the distinction of being one of two cars to run the 500 on the original tires.

Among the Also-Rans

Of the absentees, John de Palma had extremely bad luck and the failure which caused him to retire in the forty-second lap could not be blamed upon his accident in practice. After making a good pace till his first and only stop, he found the flywheel running out of truth, owing either to it being loose on the shaft or to the built-up crankshaft having loosened at the flywheel end.

The Purcell stripped the timing gear which drives the water pump, during the thirteenth lap, and the case obviously was hopeless, so this car was the first to give up the contest.

Mais, on the Mais Special, was troubled with a flooding carbureter and stopped for adjustment after covering only three laps. Pulling up again for the same cause after the twenty-fifth lap, he overshot the pit, instead of backing to it, as he should have done, ran around the road behind the pits to return to his proper place. This leaving the course automatically disqualified the car.

After making a number of laps extremely slowly, the Bugatti failed to put in an appearance, having broken down on the backstretch. There is no proof that such is the case, but it seems likely that the lubrication system is at fault or not equal to the power obtainable from modern carbureters.

Early elimination of the little Cornelian was, from a mechanical standpoint, one of the regretted results of the pace set, because of the remarkable speed shown for so small a motor – nearly 75 miles an hour for over 190 miles. The trouble was a broken valve, which fell inside the cylinder and did considerable damage to the motor. It seemed to be under-cooled, as water was taken in three times during the 3 hours that the car ran; the only mechanical work done consisted of a change of spark plugs. Reports of the pit stops show two curiously contradictory things, these being, first, that the fastest cars of foreign manufacture had no plug trouble, three of the fastest American machines were almost equally free from it, but the majority of the contestants were sufferers. It was the Mercedes and Peugeot only that had no spark plug difficulties during the practice for last year’s French grand prix, every other car in that race having ignition trouble. The Sunbeams have never been able to overcome the tendency for the plugs to fail and it is only the slower of the American cars that seem fairly free. Even amongst the slowest, however, there was a good deal of plug changing done.

Ignition Troubles

Since Peugeot and Mercedes have found the secret, there seems no reason why other people should not do so and the probability is that the secret is simply to prevent the plug from getting higher than some certain temperature.

A trick which has not yet been tried would be to use plugs of a much larger size than the standard pattern, say of double the diameter, for this would give wider insulating areas and enable better allowance to be made for expansion. The idea is not new and is the property of a plug maker, but it has not yet been tried out. Of course, there is the other attitude possible, namely, that if Peugeot and Mercedes can make motors to take ordinary plugs, then other people should be able to do likewise. But even if this view is accepted, the other scheme should be worthy of experiment.

Once again, the experience of the 500-mile race shows that it is useless to hope to win a race of this sort unless you are safe to go through without touching a spanner or even lifting the hood. The race of a year or two hence will have no pit work except the changing of tires and perhaps the supply of gasoline. Those who have mechanical troubles, however slight, will retire gracefully at the first warning.

Race Victory for Cord Tires; Two Cars Need No Casings

INDIANAPOLIS, IND., May 31. – When René Thomas stepped out of his blue car to the burning bricks of the speedway after winning the 1914 classic, the Frenchman made the statement that he did not believe the record of 82 miles an hour that he set up would be broken for some time, because tires could not stand a faster pace. Today’s results proved the victor of the 1914 race not so good a prophet as a driver, for his record was beaten by 7 miles per hour by de Palma and there were in all four machines that eclipsed Thomas‘ time of last year. This surprisingly fast pace at which the Mercedes reeled off the 500 miles today can be credited to three different factors.

The first of the factors, and possibly the least vital, is that of the weather conditions. The weather today and for the whole week previous has been ideal for obtaining high average speed in today’s event. The brick track was cool; the almost continuous rain of the last few days has soaked the surface and the cool, slightly moist air has made conditions for motor efficiency as nearly perfect as possible. Likewise, it has been partially responsible for a surprising increase in tire mileage and high speed, because instead of adding heat to the tortured tires bouncing and grinding over the surface, the bricks today have assisted in carrying off the heat.

The tires also were favored this year by the decrease in the piston displacement limit, simply because the smaller motors required that the cars be lighter. Thus there was less weight for the casings to carry and they could be run at lower tire pressure, which meant that blowouts would be less frequent and tire mileage thus increased.

But the one factor that had the greatest effect in rendering the Frenchman’s prediction hasty is the surprising improvement in the tires themselves. Today’s race was a cord tire race and it was a cord tire that was responsible largely for the unexpectedly high speed of the leading contestants.

Cord tires, a comparatively recent introduction to America, generally have been conceded to be somewhat faster during their lifetime than fabric tires, but until today there always had been some misgiving amongst the general public as to their wearing qualities, particularly for continued high-speed work. The race today seems to have proven pretty effectively that cord tires are being made to give long life as long life goes in races-and certainly not to detract from the speed.

Twenty-two of the twenty-four cars lined up for the start were equipped with cord tires. Every car that finished was equipped with cord tires, and two of them finished with the same tires on all four wheels as when they started, a thing unprecedented on the Indianapolis oval.

Silvertown cords were the equipment on every car to finish the race, the Goodrich company sharing with the Bosch concern in the honor of having exclusive equipment on the cars in the money.

Wire Wheels a Factor

There is possibly a fourth factor in this tire situation. The almost universal use of wire wheels on speed mounts. It hardly can be taken as sufficient evidence to make a general statement, but nevertheless the fact remains that Ralph Mulford’s Duesenberg, which was the only one equipped with wood wheels, had an extraordinary amount of tire trouble. During the 312 miles Mulford was in the race he changed eight tires. This is double the average number of changes.

It is interesting to note that the average tire changes for the twenty-four cars that started was four, and also that of the eleven cars to complete the 500-mile marathon. The average number of tires used per car was five; that is, each car to finish the race averaged a tire every 100 miles.

As a matter of comparison it might be noted that the other two Duesenbergs, practically identical in design and weight with that of Mulford’s, but equipped with wire wheels, were much more fortunate. Alley made the distance without a tire change, and his team-mate, O’Donnell, changed only two.

Willie Haupt’s Emden, which wound up the matinee by rolling into eleventh place at a speed of less than 71 miles an hour, made a tire record equal to that of Alley’s, as it rode all the way on the same set of Silvertowns with which it started. For consistency in running, the Emden is entitled to a higher place on the roll of honor than its speed would indicate. It seems to have imbibed some of the dogged persistence indicated by its German name, and gives promise of being heard from as frequently this season from the speedways as its namesake was on the ocean. Haupt made only two stops in the 500 miles; these for spark plugs and supplies. He just kept plugging away at 70 miles an hour.

To begin at the other end of the list, de Palma played the conservative, changing tires at both of his set stops, replacing two of them at one time and all four another, although the tires did not show excessive wear. Resta likewise took advantage of his stops at the pits for supplies to put on new casings, changing all four tires both times. Of the Stutzes, Anderson and Cooper made more tire changes than any of the other cars that finished, each of them putting on nine tires. During Wilcox’s four stops he changed eight tires.

Burman made six tire changes, Carlson almost made a record by going the distance with only one tire change. Von Raalte’s Sunbeam used up eight casings.

Photo captions.

Page 17.

AT THE COMPLETION OF 300 MILES, DE PALMA CHANGED ALL FOUR WHEELS ON HIS MERCEDES AND FILLED ALL TANKS IN PREPARATION FOR HIS 100-MILE DASH.

TIRE CHANGE THAT COST RESTA THE LEAD THAT HE NEVER REGAINED.

Page 18.

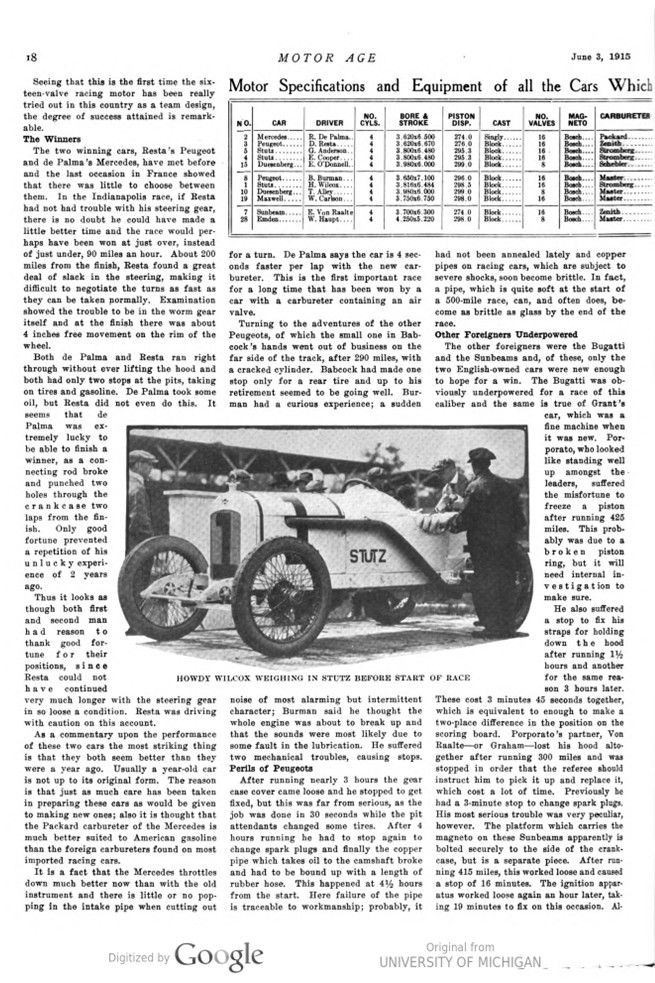

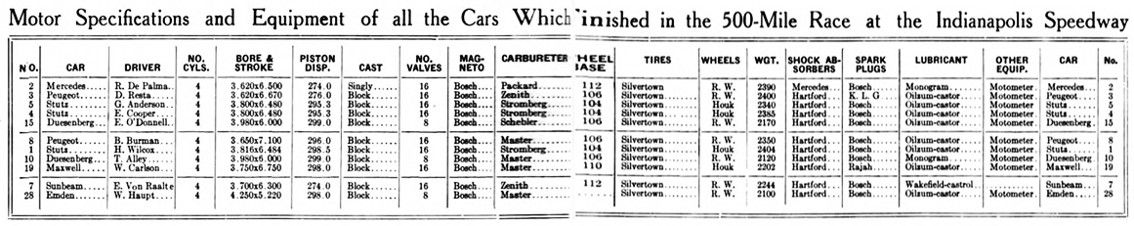

Motor Specifications and Equipment of all the Cars Which Finished in the 500-Mile Race at the Indianapolis Speedway

NO. – CAR – DRIVER – NO. CYLS. – BORE & STROKE – PISTON DISP. – CAST – NO. VALVES – MAGNETO – CARBURETER – WHEELBASE – TIRES – WHEELS – WGT. – SHOCK ABSORBERS – SPARK PLUGS – LUBRICANT – OTHER EQUIP. – CAR NO.

HOWDY WILCOX WEIGHING IN STUTZ BEFORE START OF RACE

Page 19 MOTOR AGE

OFFICIALS ORDER VON RAALTE TO FIND BONNET AND PUT IT ON SUNBEAM

Page 20 MOTOR AGE

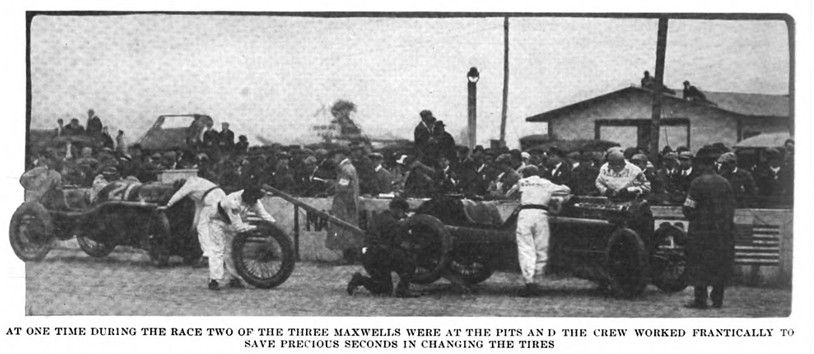

AT ONE TIME DURING THE RACE TWO OF THE THREE MAXWELLS WERE AT THE PITS AND THE CREW WORKED FRANTICALLY TO SAVE PRECIOUS SECONDS IN CHANGING THE TIRES

Page 21.

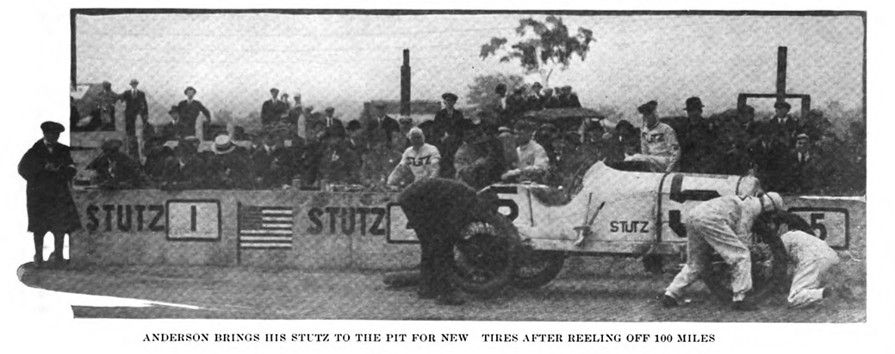

ANDERSON BRINGS HIS STUTZ TO THE PIT FOR NEW TIRES AFTER REELING OFF 100 MILES