In 1919, an apparently new magazine appeared, Automotive Industries, which was in fact the successor of The Automobile.

This is the main article of the 5 June 1919 issue, dealing with the Liberty Sweepstakes.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRIES (THE AUTOMOBILE) – Vol. XL, No. 23, June 5, 1919

Indianapolis Speedway Adopts the 3-Liter Limit for Future Races

Recent Contest Convinced Officials That 300 Cu. In. Cylinder Displacement Cars Had Developed Too Much Speed for Track — 183 Cu. In., New Maximum, Is Same as for French Grand Prix – Europe’s New Cars a Disappointment – Mechanical Notes

INDIANAPOLIS, June 2-Next year’s 500-mile classic, in the speedway here will be confined to cars having a maximum cylinder displacement of 183 cu. in. This was announced, after Saturday’s race, by Carl Fisher, the moving spirit behind the oval. Fisher said that he and his associates had become convinced that the 300 cu. in. cars have developed too much speed for the track, also that the track was too rough for 500 miles at the speed of the larger cars.

Fisher’s idea is that, as the Indianapolis track is maintained for the purpose of developing motor cars, its best service to the industry will be the encouragement of smaller engines and lighter cars. His position is that there are many more cars being made with a smaller displacement than 300 cu. in. than there are above that figure.

The new limitation is the 3-liter limit adopted for the French Grand Prix and is the size to which all of the new European racing models will be built. With the support of the French rule, it is not anticipated that there will be any objection to this decision on the part of the Indianapolis officials. It will probably encourage European competition, but it will not lessen the advantage that will come to American racing and the American industry. It is worthy of note that Boillot’s baby Peugeot is even smaller than the new limit, and this car ran well until it turned over within 20 miles of the finish, when it was in third place.

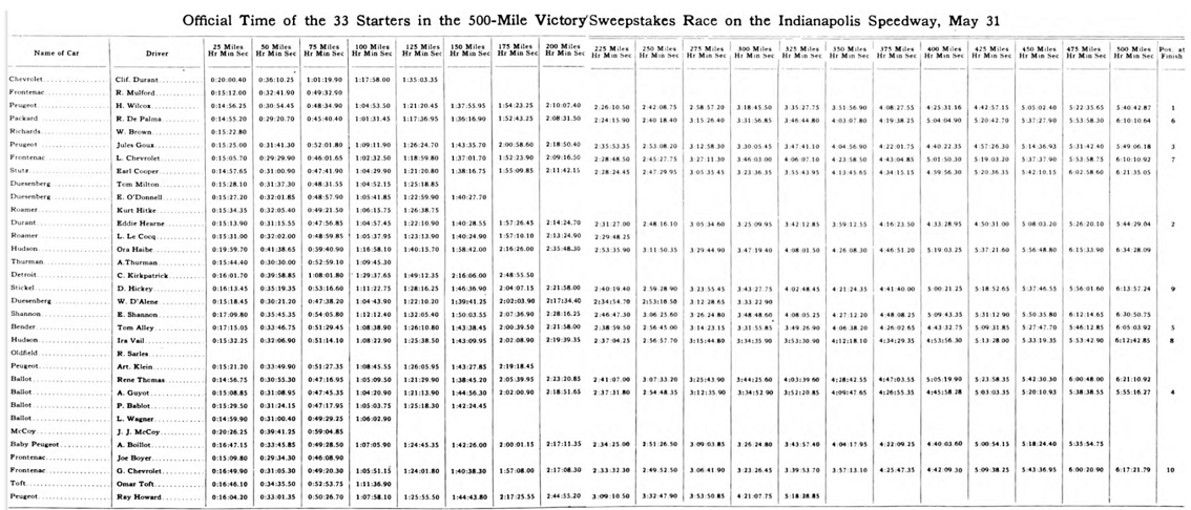

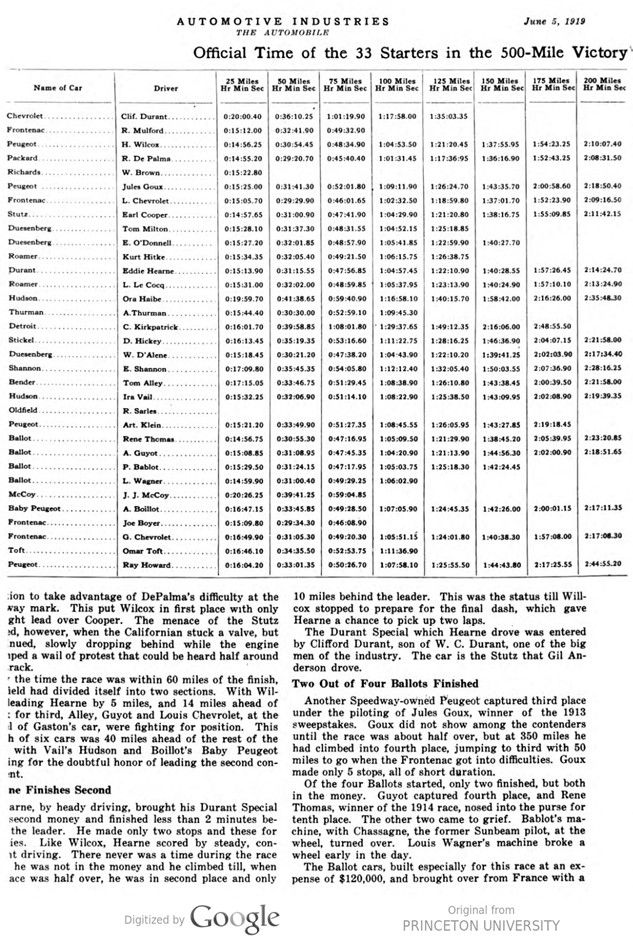

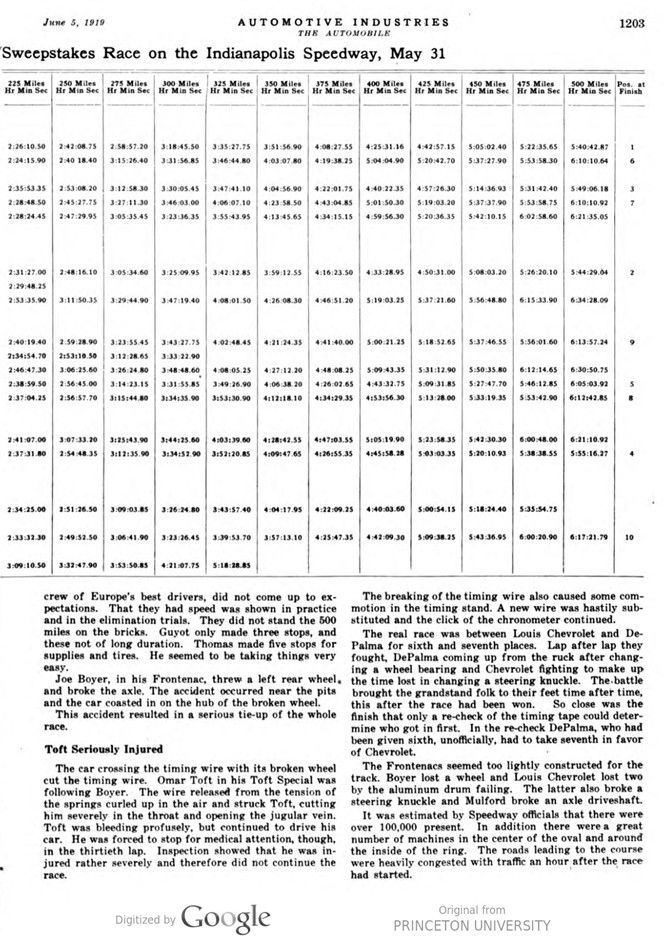

The victory of Howard Wilcox, driving a Speedway-owned Peugeot, was not a victory of speed so much as it was a victory of preparedness, thorough acquaintance with the track, and generalship, combined, as always, with good luck. The Peugeot is the same car with which the late Aitken campaigned so successfully. It has been worked over so much and so many parts of American manufacture incorporated, that it cannot now be called foreign. Wilcox has it in such shape that he went through the race without having to make adjustments. His three short halts at the pits were for tires and supplies. He did not drive exceptionally hard; made no exceptionally fast laps. He won because others, who drove faster while on the track, could not keep going.

The race this year did not make a record for the distance. Wilcox’s time was more than 10 minutes longer than DePalma’s record for the 500 miles in 1915. Saturday’s average speed was 87.12 m.p.h., 2.72 m.p.h. less than the 1915 records.

If DePalma or Gaston Chevrolet, who between them led the field for the first half of the race, could have kept on the track, the record for the distance would have been broken. DePalma led the field for the first 150 miles at an average of better than 92 m.p.h. His stop threw Chevrolet in the lead and the speed dropped to 90 m.p.h. The Italian gained the lead again and pushed the pace up to 91.6 m.p.h., until valves and wheel bearings checked him. His speed of 92.20 at the 100-mile mark is a track record for that distance.

Wilcox led almost the entire last half of the race, taking the pace when the Packard was held at the pits for repairs. The Peugeot, which the winner drove, was well up among the leaders most of the way. It was in third place at 25 miles and second at 50. Then Wilcox fell out of the money for nearly 50 miles, but, climbing steadily, at 125 miles, he was back in third place and crowding DePalma and Gaston Chevrolet. He took second place when the Frontenac hung up at the pits at 200 miles and was in position to take advantage of DePalma’s difficulty at the halfway mark. This put Wilcox in first place with only a slight lead over Cooper. The menace of the Stutz ceased, however, when the Californian stuck a valve, but continued, slowly dropping behind while the engine thumped a wail of protest that could be heard half around the track.

By the time the race was within 60 miles of the finish, the field had divided itself into two sections. With Wilcox leading Hearne by 5 miles, and 14 miles ahead of Goux for third, Alley, Guyot and Louis Chevrolet, at the wheel of Gaston’s car, were fighting for position. This bunch of six cars was 40 miles ahead of the rest of the field, with Vail’s Hudson and Boillot’s Baby Peugeot fighting for the doubtful honor of leading the second contingent.

Hearne Finishes Second

Hearne, by heady driving, brought his Durant Special into second money and finished less than 2 minutes behind the leader. He made only two stops and these for supplies. Like Wilcox, Hearne scored by steady, consistent driving. There never was a time during the race when he was not in the money and he climbed till, when the race was half over, he was in second place and only 10 miles behind the leader. This was the status till Willcox stopped to prepare for the final dash, which gave Hearne a chance to pick up two laps.

The Durant Special which Hearne drove was entered by Clifford Durant, son of W. C. Durant, one of the big men of the industry. The car is the Stutz that Gil Anderson drove.

Two Out of Four Ballots Finished

Another Speedway-owned Peugeot captured third place under the piloting of Jules Goux, winner of the 1913 sweepstakes. Goux did not show among the contenders until the race was about half over, but at 350 miles he had climbed into fourth place, jumping to third with 50 miles to go when the Frontenac got into difficulties. Goux made only 5 stops, all of short duration.

Of the four Ballots started, only two finished, but both in the money. Guyot captured fourth place, and Rene Thomas, winner of the 1914 race, nosed into the purse for tenth place. The other two came to grief. Bablot’s machine, with Chassagne, the former Sunbeam pilot, at the wheel, turned over. Louis Wagner’s machine broke a wheel early in the day.

The Ballot cars, built especially for this race at an expense of $120,000, and brought over from France with a crew of Europe’s best drivers, did not come up to expectations. That they had speed was shown in practice and in the elimination trials. They did not stand the 500 miles on the bricks. Guyot only made three stops, and these not of long duration. Thomas made five stops for supplies and tires. He seemed to be taking things very easy.

Joe Boyer, in his Frontenac, threw a left rear wheel and broke the axle. The accident occurred near the pits and the car coasted in on the hub of the broken wheel. This accident resulted in a serious tie-up of the whole race.

Toft Seriously Injured

The car crossing the timing wire with its broken wheel cut the timing wire. Omar Toft in his Toft Special was following Boyer. The wire released from the tension of the springs curled up in the air and struck Toft, cutting him severely in the throat and opening the jugular vein. Toft was bleeding profusely, but continued to drive his car. He was forced to stop for medical attention, though, in the thirtieth lap. Inspection showed that he was injured rather severely and therefore did not continue the race.

The breaking of the timing wire also caused some commotion in the timing stand. A new wire was hastily substituted and the click of the chronometer continued.

The real race was between Louis Chevrolet and DePalma for sixth and seventh places. Lap after lap they fought, DePalma coming up from the ruck after changing a wheel bearing and Chevrolet fighting to make up the time lost in changing a steering knuckle. The battle brought the grandstand folk to their feet time after time, this after the race had been won. So close was the finish that only a re-check of the timing tape could determine who got in first. In the re-check DePalma, who had been given sixth, unofficially, had to take seventh in favor of Chevrolet.

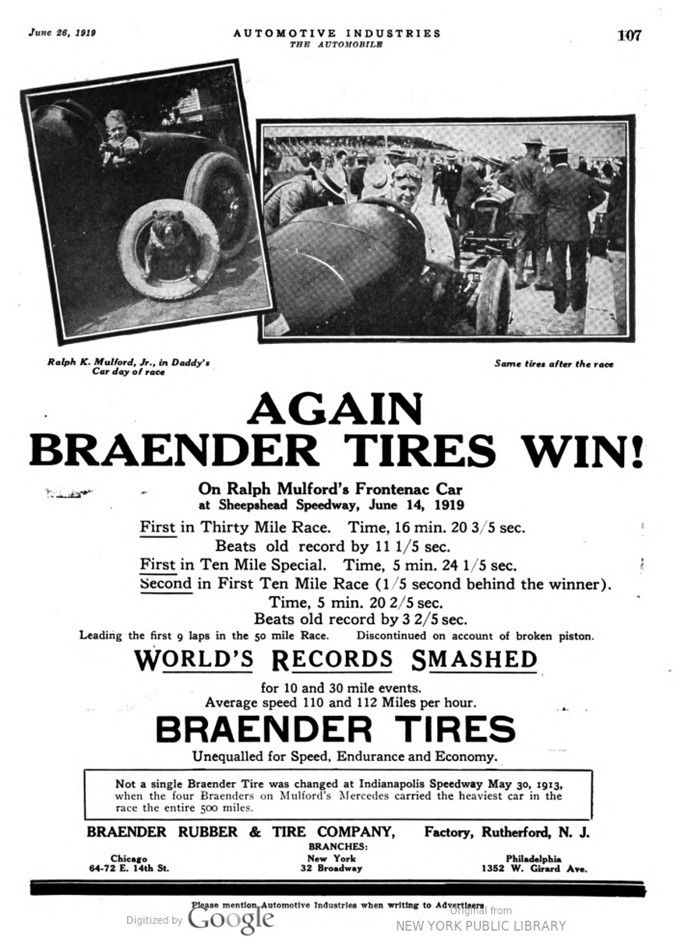

The Frontenacs seemed too lightly constructed for the track. Boyer lost a wheel and Louis Chevrolet lost two by the aluminum drum failing. The latter also broke a steering knuckle and Mulford broke an axle driveshaft.

It was estimated by Speedway officials that there were over 100,000 present. In addition, there were a great number of machines in the center of the oval and around the inside of the ring. The roads leading to the course were heavily congested with traffic an hour after the race had started.