Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

MoToR, Vol. 24, July 1915

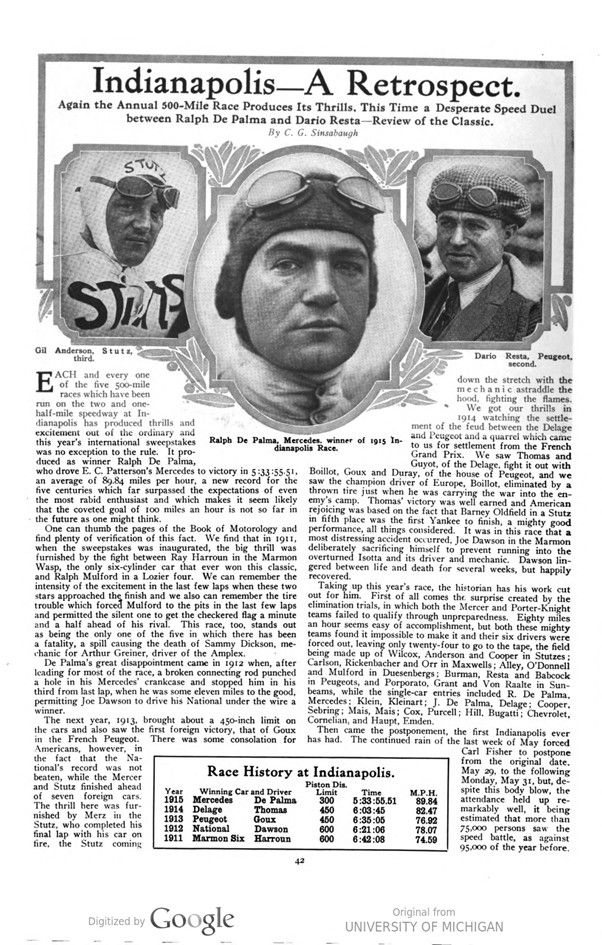

Indianapolis A Retrospect.

Again the Annual 500-Mile Race Produces Its Thrills, This Time a Desperate Speed Duel between Ralph De Palma and Dario Resta-Review of the Classic.

By C. G. Sinsabaugh

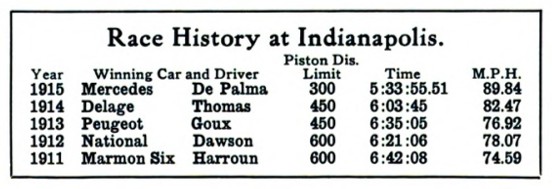

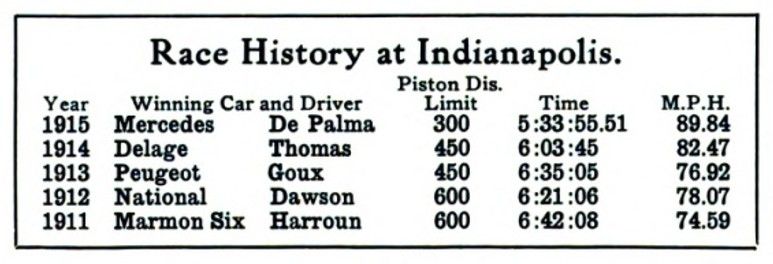

EACH and every one of the five 500-mile races which have been run on the two and one-half-mile speedway at Indianapolis has produced thrills and excitement out of the ordinary and this year’s international sweepstakes was no exception to the rule. It produced as winner Ralph De Palma, who drove E. C. Patterson’s Mercedes to victory in 5:33:55.51, an average of 89.84 miles per hour, a new record for the five centuries which far surpassed the expectations of even the most rabid enthusiast and which makes it seem likely that the coveted goal of 100 miles an hour is not so far in the future as one might think.

One can thumb the pages of the Book of Motorology and find plenty of verification of this fact. We find that in 1911, when the sweepstakes was inaugurated, the big thrill was furnished by the fight between Ray Harroun in the Marmon Wasp, the only six-cylinder car that ever won this classic, and Ralph Mulford in a Lozier four. We can remember the intensity of the excitement in the last few laps when these two stars approached the finish, and we also can remember the tire trouble which forced Mulford to the pits in the last few laps and permitted the silent one to get the checkered flag a minute and a half ahead of his rival. This race, too, stands out as being the only one of the five in which there has been a fatality, a spill causing the death of Sammy Dickson, mechanic for Arthur Greiner, driver of the Amplex.

De Palma’s great disappointment came in 1912 when, after leading for most of the race, a broken connecting rod punched a hole in his Mercedes‘ crankcase and stopped him in his third from last lap, when he was some eleven miles to the good, permitting Joe Dawson to drive his National under the wire a winner.

The next year, 1913, brought about a 450-inch limit on the cars and also saw the first foreign victory, that of Goux in the French Peugeot. There was some consolation for Americans, however, in the fact that the National’s record was not beaten, while the Mercer and Stutz finished ahead of seven foreign cars. The thrill here was furnished by Merz in the Stutz, who completed his final lap with his car on fire, the Stutz coming down the stretch with the mechanic astraddle the hood, fighting the flames. We got our thrills in 1914 watching the settlement of the feud between the Delage and Peugeot and a quarrel which came to us for settlement from the French Grand Prix. We saw Thomas and Guyot, of the Delage, fight it out with Boillot, Goux and Duray, of the house of Peugeot, and we saw the champion driver of Europe, Boillot, eliminated by a thrown tire just when he was carrying the war into the enemy’s camp. Thomas‘ victory was well earned, and American rejoicing was based on the fact that Barney Oldfield in a Stutz in fifth place was the first Yankee to finish, a mighty good performance, all things considered. It was in this race that a most distressing accident occurred, Joe Dawson in the Marmon deliberately sacrificing himself to prevent running into the overturned Isotta and its driver and mechanic. Dawson lingered between life and death for several weeks, but happily recovered.

Taking up this year’s race, the historian has his work cut out for him. First of all comes the surprise created by the elimination trials, in which both the Mercer and Porter-Knight teams failed to qualify through unpreparedness. Eighty miles an hour seems easy of accomplishment, but both these mighty teams found it impossible to make it and their six drivers were forced out, leaving only twenty-four to go to the tape, the field being made up of Wilcox, Anderson and Cooper in Stutzes; Carlson, Rickenbacher and Orr in Maxwells; Alley, O’Donnell and Mulford in Duesenbergs; Burman, Resta and Babcock in Peugeots, and Porporato, Grant and Von Raalte in Sun- beams, while the single-car entries included R. De Palma, Mercedes; Klein, Kleinart; J. De Palma, Delage; Cooper, Sebring; Mais, Mais; Cox, Purcell; Hill, Bugatti; Chevrolet, Cornelian, and Haupt, Emden.

Then came the postponement, the first Indianapolis ever has had. The continued rain of the last week of May forced Carl Fisher to postpone from the original date. May 29, to the following Monday, May 31, but despite this body blow, the attendance held up remarkably well, it being estimated that more than 75,000 persons saw the speed battle, as against 95,000 of the year before.

But inasmuch as the general admission had been increased from $1 to $2, it is figured that financially the race produced as much revenue as in 1914.

The 75,000 were well repaid for the wait, however, for they saw a race the equal of which cannot be found in the Book of Motorology. They saw two of the leading drivers in the world, Ralph De Palma and Dario Resta, fight it out to the bitter end. They saw De Palma outgeneral his great rival and, by his driving skill, bring home the big end of the purse. They saw Anderson in the Stutz, the first American to finish, stick grimly to his task and land, a brilliant third. They also saw another Stutz, driven by Cooper, drop into fourth and Wilcox in the third Stutz land seventh; they saw O’Donnell in a Duesenberg get fifth; Burman in a Peugeot sixth; Alley in a Duesenberg eighth; the Carlson-Hughes Maxwell ninth, and Von Raalte in a Sunbeam tenth, while Haupt in the Emden was permitted to finish eleventh.

The first four all beat the previous 500-mile record, held by Thomas in a Delage, despite the fact that the motors this year were much smaller, the limit being 300 inches as against 450 last year and the year before. The averages of the ten finishers were: R. De Palma, 89.84; Resta, 88.91; Anderson, 87.60; Cooper, 87.11; O’Donnell, 81.47; Burman, 80.36; Wilcox, 80.14; Alley, 79.97; Carlson-Hughes, 78.96; Von Raalte, 75.79.

The story of the race itself shows Anderson the early leader. At the first century post Resta was in front, but at the end of 200 miles De Palma led Resta by forty seconds. Then came the duel between the two for the remainder of the journey. Resta’s was the faster car and he would gain on De Palma on the straights, but on the bends the Mercedes pilot’s driving counted and he would pick up the slack. At 400 miles De Palma apparently had Resta beaten, barring the unforeseen, although the margin of time between the two was slight. A skid by Resta which slammed the Peugeot into the retaining wall so damaged the steering gear that after that the Vanderbilt cup holder was extra cautious. Later on, De Palma had his scare, when, at three laps from home, history repeated itself. As in 1912, a broken connecting rod punched a hole in the Mercedes‘ crankcase, but luckily for De Palma he was able to keep a-going and finish – not having to quit as he did in 1912, when victory seemed his.

In the 500 miles, De Palma stopped twice at the pits. the first time at the sixty-third lap, when he changed two right wheels, and again at 300 miles, when as a precautionary measure he changed all four tires and took on supplies.

The tire story of the race makes an interesting chapter. because the tires were largely responsible for the broken records. Twenty-two of the twenty-four starters used Silvertown cords, and the first ten to finish were Goodrich-shed, while the Emden, the eleventh car, was similarly equipped. Haupt did not have to change a single tire, while Alley in the Duesenberg also went the 500 miles on his original set of Silvertowns. It also is interesting to note that every car in the race carried Bosch magnetos.

Taking up the equipment of the cars that finished, we find that all used Silvertown cord tires and Bosch magnetos; all had Hartford shock absorbers, except De Palma, who used Mercedes; all had Motometers except Von Raalte, while the carbureters were as follows: De Palma, Packard; Resta and Von Raalte, Zenith; Anderson, Wilcox and Cooper, Stromberg; O’Donnell, Schebler; Burman, Carlson, Alley Haupt, Master; De Palma and Alley used Monogram oil; Resta, Anderson, Cooper, O’Donnell, Burman, Wilcox, Carlson and Haupt, Oilzum-castor, and Von Raalte, Wakefield- castor. De Palma, Resta, O’Donnell, Alley, Von Raalte and Haupt used Rudge-Whitworth wire wheels, while Houks were fitted to the cars driven by Anderson, Cooper, Wilcox and Carlson. All had Bosch spark plugs except Resta, who used K. L. G., and Carlson, who used Rajahs.

The review of the 1915 race would not be complete without reference to the brilliant performances of the three Stutz cars, which established a record never before made in the classic by getting the entire team into the prize money, two of the cars beating the previous mark for the distance, and Anderson and Cooper being beaten only after a hard battle. As in 1914, Stutz was the first American car to finish.

In making this showing Stutz is only living up to his past reputation, for in looking back over the five races, one finds that Stutz has finished in the money in every one of them. In 1911 he started a single car, driven by Anderson, who finished eleventh. The next year Merz in the Stuts was third, and the next year he was fourth and Zengel, his team-mate, was sixth. Last year Oldfield, the first American finisher, was fifth. No other maker can boast of this Indianapolis record for consistency. Those devotees of the valve-in-the-head type of motor who always have maintained that this form of construction reduces weight, is more economical of fuel, has a snappier action (due probably to increased compression), and, above all, delivers more power for the same cylinder dimensions, have received no uncertain confirmation of their contentions in the result of the race.

Out of the twenty-four actual starters fifteen motors were fitted with overhead valves, including the foreign veterans of the track which finished in first and second places, but whose performances were undoubtedly overshadowed by the excellent team work which resulted in the three Stutz entries, fitted with an absolutely new type of valve-in-the-head engine, occupying the third, fourth and seventh positions at finish a performance which certainly stands as a record on American tracks, and also excels anything accomplished abroad, with the possible exception of the Mercedes‘ work at last year’s Grand Prix.

Another interesting point in connection with this year’s race is that now all the big cups are held by two men – Ralph De Palma and Resta. Because of his leading at 200, 300 and 400 miles, De Palma has added to his collection the Remy brassard and trophy, the Prestolite trophy and the $10,000 Wheeler & Schebler cup, which already included the Elgin National and the Cobe cup, won in the Elgin road races last fall. Resta who won both the Vanderbilt and the Grand Prize at the San Francisco exposition, picked up the G. & J. shield for leading at the century mark.

Statistics show that 141 cars have started in all of the sweepstakes, representing fifty-four different makes, of which ten come from across the Atlantic. Of this total twenty-five makes are represented with only one start each. As showing the international character of the race, the foreigners which have lined up for this classic include such well-known makes as the Peugeot and Delage of France, the Mercedes, Opel, Benz and Bugatti of Germany, the Sunbeam of England, the Excelsior of Belgium, and the Fiat and Isotta of Italy. A review of these statistics shows that Stutz has started the greatest number of cars-thirteen, of which number eight have finished inside the money. Mercedes bas started seven times and finished four times; Mercer has started eight and finished three, and National six and finished three. Peugeot has had eight starts, getting money with five, while Sunbeam three times with six starts. The following table shows those makes which have started more than once:

Make: Starts: In Money: (*I won’t list names and other corresponding figures; please see jpegs, GrocerJack*)

Those which have started once and have finished in the money include White, Tulsa, Excelsior and Beaver Bullet. Those which have started and have failed to finish in the money have been Inter-State, Velie, McFarlan, Cole, Apperson, Alco, Marquette, Lexington, Opel, Anel, Henderson, Nyberg, King, Braender Bulldog, Gray Fox, Emden, Sebring, Kleinert, Cornelian, Mais and Purcell.

Eighty-three drivers have participated in the five races, of which number only three – Wilcox, Mulford and Anderson – have started in each of them. R. De Palma, Wishart, Tetzlaff and Grant have started four times; Merz, W. Endicott, Knipper, Burman, Disbrow, Bragg, Rickenbacher and Haupt three times, and Bruce-Brown, Dawson, Jenkins, Hearne, Tower, Liesaw, Goux, Guyot, Earl Cooper and Klein, two each. The records are as follows:

Make: Starts: In Money: (*I won’t list names and other corresponding figures; please see jpegs, GrocerJack*)

Those who have started once and have finished in the money include Harroun, Turner, Belcher, Cobe, Hughes, Zengel, Horan, Pilette, Clark, Thomas, Duray, Oldfield, Christiaens, C. Keene, Resta, O’Donnell, Alley and Von Raalte. Those who have started and not cashed are Frayer, Bigelow, H. Endicott, Hall, Beardsley, Fox, Delaney, Marquette, Aitken, Jones, Strang, C. Basle, A. Chevrolet, Ellis, Greiner, Dingley, Matson, Knight, Ormsby, Evans, J. Nikrant, Trucco, Herr, Boillot, Friedrich, Chandler, Gilhooley, Chassagne, Brock, Orr, Porporato, J. Cooper, Babcock, L. Chevrolet, J. De Palma, Mais, Hill and Cox.

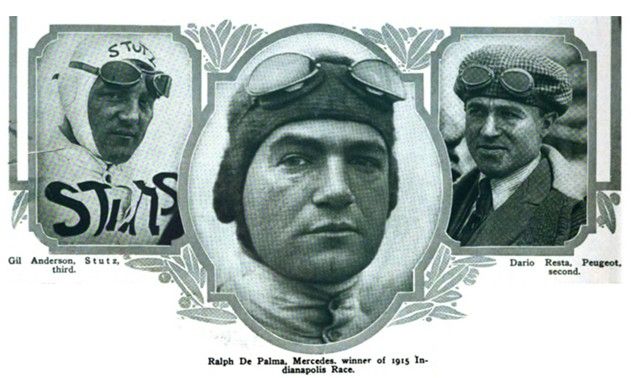

Picture captions.

Page 42.

STUTZ Gil Anderson, Stutz, E third. Ralph De Palma, Mercedes. winner of 1915 Indianapolis Race.

Dario Resta, Peugeot, second.

Page 43.

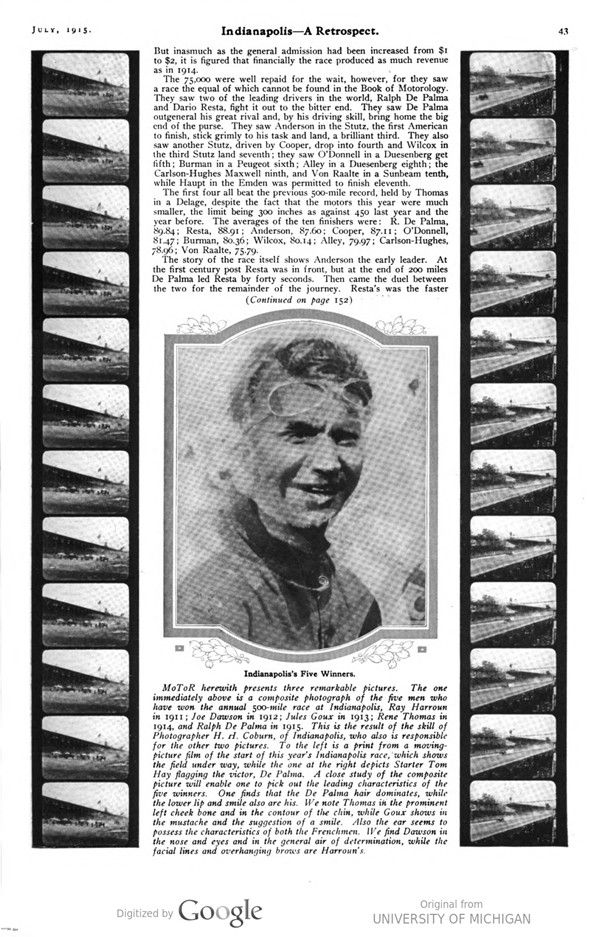

Indianapolis’s Five Winners.

MOTOR herewith presents three remarkable pictures. The one immediately above is a composite photograph of the five men who have won the annual 500-mile race at Indianapolis, Ray Harroun in 1911; Joe Dawson in 1912; Jules Goux in 1913; Rene Thomas in 1914, and Ralph De Palma in 1915. This is the result of the skill of Photographer H. H. Coburn, of Indianapolis, who also is responsible for the other two pictures. To the left is a print from a moving-picture film of the start of this year’s Indianapolis race, which shows the field under way, while the one at the right depicts Starter Tom Hay flagging the victor, De Palma. A close study of the composite picture will enable one to pick out the leading characteristics of the five winners. One finds that the De Palma hair dominates, while the lower lip and smile also are his. We note Thomas in the prominent left cheek bone and in the contour of the chin, while Goux shows in the mustache and the suggestion of a smile. Also the ear seems to possess the characteristics of both the Frenchmen. We find Dawson in the nose and eyes and in the general air of determination, while the 1 facial lines and overhanging brows are Harroun’s.