Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Motor Age, Vol. XXV (225), No. 19, May 7, 1914

History-Making Racing Cars, Part I

What They Did and How They Did It

By. Darwin S. Hatch

EDITOR’S NOTE – Herewith is presented the first of a series of two articles which should prove most interesting to followers of racing. It deals entirely with the speed creations which have done so much to bring motoring into popular favor as a major sport, presenting facts about the old timers which will be new to the present generation, and in the case of the racing cars of recent years, recalling the facts that have made them famous. The present article necessarily deals with the veterans, the 999’s, the Winton Bullets, the Whistling Billys, the Peerless Green Dragons and the Stanleys of other days, to which credit is due as pioneers in a sport that now ranks with the highest. In the issue of May 14 we will learn about the more modern creations. Doubtless, readers will recall other cars that may not be mentioned in this series, but Motor Age has endeavored to tear from the pages of history facts about racing cars that really did something.

Sing now, O muse! of days of old

When cars were slow but men as bold

As men who leer at Fate to-day

And jeer at pitfalls in the way:

Of heroes crowned by speed.

Battered and bent, these greybeards of speed are cheered no more. They have given way before the grease-spattered creations of a new generation of builders. The crowds that once paid them vociferous homage now recount the achievements of de Palma’s Mercedes, sponsored by Tragedy and Triumph at its christening; the Blitzen Benz, in which Bob Burman earned the title of speed king; the 300-horsepower Fiat that carried Duray over the sands of Ostend at a rate of 142.9 miles per hour; the twelve-cylinder Sunbeam, holder of the world’s 1-hour record; the dependable Stutz at whose wheel Earl Cooper was crowned national champion; and the Jay- Eye-See, monster fire-spitter of the hippodrome circuit.

Many of the mechanical patriarchs that roared a menacing challenge at Brighton Beach and Daytona-Ormond and in the classic Gordon Bennetts of a decade or more ago, lie silent, forgotten, unhonored on junk heaps. Others, like the around-the-world Thomas, are prized as relics. Some, despite their age and years of faithful service, still respond to the foot of a new master when he steps upon the throttle.

Of the men who courted Fame at the steering wheels of these antiques, only a few retain their allegiance to the racing car. In the races held at the dawn of the new century, it was the rule rather than the exception that the designer and builder of the car was its driver and many of the makes of cars that are household words to-day made their first bid for popularity with their creators guiding them on uncertain and tortuous journeys. Henry Ford, Alexander Winton, Windsor T. White, Percy Owen, Edgar Apperson and F. E. Stanley, hailed as dare-devils in the early days of the sport, now control plants that grind out a profitable grist of motor cars annually. Other drivers of the glorious yesterdays are now active in the motor car industry or its allied interests – Carl Fisher with his speedway and Prest-o-lite connections; Webb Jay with his accessories; Charles B. Shanks with the Class Journal Co.

Long a Popular Idol

Of all the drivers who became famous when racing in America was in its infancy, only one retains his prestige, only one continues to be a popular idol of the speed fans. That driver is Barney Oldfield – good-natured, cigar-chewing Barney Oldfield, the game’s Peter Pan – whose checkered career is so interwoven with the history of the early speed cars in this country that a story of his experiences must include the triumphs of most of the older racing machines.

Oldfield’s first experience, his entrance to motor car racing, was in 1902 with the original Ford 999. Before that time, he was a bicycle rider and in the spring of 1902 Tom Cooper, an old-time bicycle champion racer, loaned him a motorcycle tandem. With this he was very successful in Salt Lake City and gained his first gasoline engine experience there. While he was in Salt Lake City, Cooper had formed some sort of a combination with Henry Ford, who had been dabbling at motor cars for 5 years previously. Cooper wrote Oldfield that he was building two racing cars of enormous power and on their completion expected to tour the country and give exhibition races.

Toward the end of the season when the cars were nearing completion, Oldfield went to Detroit as a mechanic and helper for Cooper and Ford. One car was painted red and the other yellow. The red one had Ford’s name on the seat and the other one had Cooper’s. The red one was finished first and taken out to the old Grosse Pointe 1-mile track for its first trial. The trial was a flat failure for the engine was „as hot as mother’s cook stove,“ according to Oldfield, and it looked like Cooper and Ford had wasted not only a lot of money but a great deal of time and energy as well.

Ford finally got disgusted with the machines and turned the red one over to a piano tuner in Detroit. Ford wanted to wash his hands of the whole affair and agreed to sell Cooper the two cars for the actual cash he had put in. In addition, Cooper was to assume all outstanding indebtedness and was to pay for the machinery in the shop, which consisted of a drill press, lathe and emery wheel. Hence, Cooper practically was forced to buy Ford out before the latter would produce the red car and help finish up the yellow one. When they were finished up in a crude way both Cooper and Oldfield were confident that they would run, so that when Carl Fisher and Earl Kiser, later driver of the Winton Bullet, promoted a race meet in Dayton, Ohio, the two cars appeared there and it was at this time that the yellow car got its name of 999.

Ford 999 Makes Debut

The two cars did not run any better at Dayton than they had at Grosse Pointe and they were shipped to Toledo, Ohio, where Cooper and Oldfield, together with „Spider“ Huff, set to work to fix them up so that they could be entered in the race meet to be held at Grosse Pointe track, October 1902, and in which Alexander Winton, Charles B. Shanks, Windsor T. White, Harry Harkness, and several others, who then were prominent in the sport, were to participate.

The cars were finished after many hours of night and day work and after trying them out one morning at 3 a.m. and finding that they actually ran, they were shipped to Detroit on the boat arriving there about 2 o’clock in the morning of the race. Cooper went to bed, but Huff and Oldfield borrowed a horse that was used for pulling a lunch wagon, and just before daylight towed the 999 out of the residence portion of the city where the engine could be started without waking up the central police station.

Up to this time Oldfield never had driven a car in spite of all the work he had been doing on them, never had ridden in a motor car but twice. On arrival at the track, Oldfield began to practice, and over the strenuous objections of Henry Ford the car was entered in a 5-mile event against Winton in his machine, Shanks in the Winton Pup, and a steamer called the Geneva. Oldfield won his first race, driving the 5-miles in 5 minutes, 28 seconds.

Oldfield and 999 Shine Together

With this auspicious beginning, Oldfield and the Ford 999 began their career together, and records fell in rapid succession. In December of that year this combination broke the world’s record for both 1 mile and 5 miles over 1-mile dirt tracks and in June, 1903, they appeared at Indianapolis at a race meet promoted by Carl Fisher, doing a mile in less than 1 minute. Hence Indianapolis, in addition to having the finest speedway in America, has the distinction of having had the first mile under the minute on a 1-mile dirt track. On the following fourth of July Oldfield and the Ford went 10 miles in less than 10 minutes.

Mechanically, the old Ford 999 was a freak even in that day, when there were no standard designs or arrangements of parts. The motor was a four-cylinder engine cast in block, one of the earliest block-cast motors. The cylinder bore was 7 inches in diameter and the stroke was 7 inches. The inlet valves were automatic; there was no crankcase, the crankshaft revolving in the open; there was no transmission, except for an expanding friction clutch; it had no worm steering gear, or steering wheel. The steering gear was connected up direct to a vertical steering column which was turned by means of handle bars.

The machine had no differentials and had 34 by 4½ inch wire wheels. The radiator was in front of the car, was made of large horizontal tubes and originally was about the biggest thing on the car, as it extended from within 3 or 4 inches off the ground to somewhat above the engine. The exhaust valves were operated by an overhead camshaft driven by a bevel gear and vertical shaft and all gearing and mechanism was open. Later the high radiator was displaced by a more compact one.

This original 999 ended an eventful career at Milwaukee when it went through the fence and killed its driver, Frank Day. The car was completely wrecked and the remnants were shipped back to the Ford factory at Detroit and junked. The mate to the 999 now is in California and is owned by Dana Burke at Santa Monica. It has been remodeled to such an extent that it resembles the original 999 very slightly. Tom Cooper had set up a number of records with this car. He formerly was a bicycle racing champion and was killed in 1906 while driving through Central Park, New York.

There was one predecessor of the Ford 999. It was driven by Henry Ford who signalized his first appearance as a racing driver by being beaten by Alexander Winton in the Winton Bullet at Grosse Pointe. He was hailed in Motor Age of October 17, 1901, as the new Detroit phenomenon.“ The car was credited with 40 horsepower and Ford said he had made a ½ mile in 26 seconds in a preliminary trial.

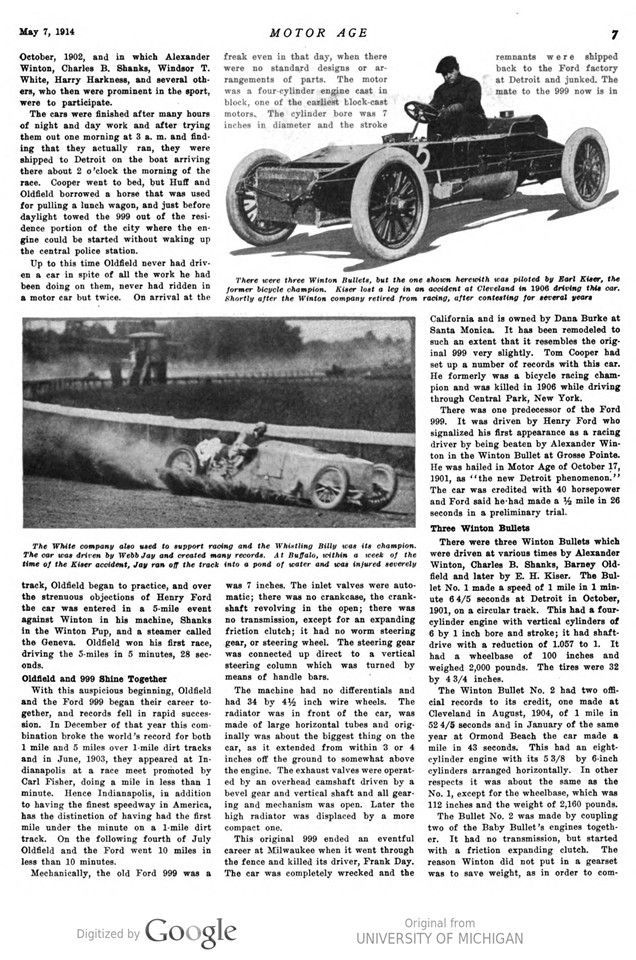

Three Winton Bullets

There were three Winton Bullets which were driven at various times by Alexander Winton, Charles B. Shanks, Barney Oldfield and later by E. H. Kiser. The Bullet No. 1 made a speed of 1 mile in 1 minute 64/5 seconds at Detroit in October, 1901, on a circular track. This had a four-cylinder engine with vertical cylinders of 6 by 1 inch bore and stroke; it had shaft-drive with a reduction of 1.057 to 1. It had a wheelbase of 100 inches and weighed 2,000 pounds. The tires were 32 by 4 3/4 inches.

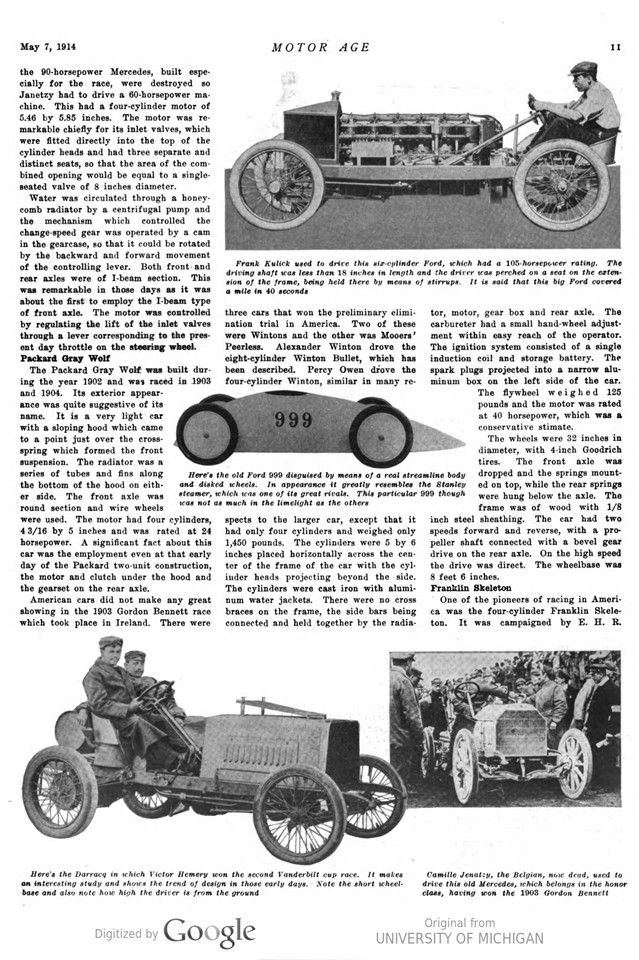

The Winton Bullet No. 2 had two official records to its credit, one made at Cleveland in August, 1904, of 1 mile in 52 4/5 seconds and in January of the same year at Ormond Beach the car made a mile in 43 seconds. This had an eight-cylinder engine with its 5 3/8 by 6-inch cylinders arranged horizontally. In other respects, it was about the same as the No. 1, except for the wheelbase, which was 112 inches and the weight of 2,160 pounds.

The Bullet No. 2 was made by coupling two of the Baby Bullet’s engines together. It had no transmission but started with a friction expanding clutch. The reason Winton did not put in a gearset was to save weight, as in order to compete in the Gordon Bennett in Europe in 1903 it had to weigh less than 2,204 pounds. This car was very fast for those days and under Oldfield’s handling, when Winton retired after the Gordon Bennett race, the former broke all the records he previously had made with the 999. The 1-mile world’s champion- ship of 43 seconds at Ormond-Daytona mentioned above, was captured by Oldfield, defeating such men as W. K. Vanderbilt Jr. and Sam. B. Stevens, both of them in high-powered Mercedes cars, which cost them something like $19,000 each, it is said.

The No. 3 Bullet did not have the speed of its predecessor, although it had an official reported speed of 1 mile in 59 seconds taken at Cleveland on a circular track in September 1903. It had four cylinders set horizontally, 5 3/8 inches by 6. Its wheelbase was 100 inches and its weight 1,850. This car was strictly up-to-date for those times, having a two- speed gearset, differential, and a steering worm. Later it was the Baby Bullet.

Peerless Green Dragon

Another car which won fame in the early days of the century owned its existence to Oldfield. This was the Peerless Green Dragon. In 1904, Oldfield went with the Peerless company and Louis P. Mooers built him a car which was christened the Green Dragon. It had great success during 1904 and 1905 until it met its Water- loo at St. Louis, when it went through the fence and was completely wrecked. It was a four-cylinder car, 6 by 6 inches in size with the cylinders cast separately and of the T-head type.

After this car was wrecked, Mooers built another car, which Oldfield also called the Green Dragon, and which was the first underslung frame built in America, if not in the world. The engine was cast in one block, 53/4 by 53/4 inches. The valves were in the head, there was no gearset, but it had a sliding clutch and a pointed vertical tube radiator whose appearance suggested its name. Oldfield drove this car for 4 years and the combination broke many world’s records.

In its day, the Stanley steamer, affectionally known as „The Bug,“ was regarded as the fastest thing on wheels. It was sent to the Ormond Beach meet in January 1906, where Marriott drove it, putting the world’s mile straightaway record at 28 1/5 seconds. It was credited with 50 horsepower and the steam was superheated by the Stanley system to a temperature of 700 degrees.

The motor was a two-cylinder double-acting engine with cylinders 4½ by 6 inches. It was claimed that with the engine running at 700 r. p. m., it was capale of developing over 100 horsepower. The valve gear was of the Stephenson link style, which is used today on locomotives. The weight of the machine exclusive of supplies was approximately 1,650 pounds and the wheelbase was 100 inches, and the tread only 54 inches. The tires were 3 inches in the front and 3½ in the rear.

It was steered by cross lever instead of a steering wheel. The frame entirely of wood, was hung on four elliptic springs inside of the body. The bottom of the car was perfectly smooth and the hood made of wood with an inverted boat appearance, having a round turtle back body with sharp prow and stern, the only opening being for the driver’s shoulders. This is one of the earliest of the consistent efforts to reduce wind resistance.

Stanley Bug a Favorite

Marriott was the foreman of the repair department at the Stanley factory. A year later Marriott brought to Ormond a new Stanley, which was said to be faster than the first one. In a record drive, however, going at what was estimated to be better than 100 miles an hour, the car overturned and was wrecked, though Marriott escaped serious injury.

At this meet when Marriott made his record there appeared another Ford racing machine. This was a six-cylinder car which practically was all engine. It was driven by Frank Kulick and in its trial for the mile record covered the distance in 40 seconds. It was credited with 105 horse- power and the six cylinders separately cast engine occupied nearly the whole frame between the front and rear axles. The driving shaft was less than 18 inches in length and the driver held a precarious position on a seat on the extension of the frame at the rear of the rear wheels. So uncertain was the driver’s position that stirrups were arranged for his feet to prevent him falling over backwards. The car had a long, pointed radiator, no gearset, and wire wheels.

This 1906 meet at Ormond was the scene also of the breaking of another record. It saw the first time a human being ever covered 2 miles in the space of 60 seconds. The car which accomplished this was the eight-cylinder Darracq and the driver was Victor M. Demogeot. The car originally was to have been driven by Hemery but because of difficulties with the officials overweighing in, Hemery attempted to withdraw all of his cars. But by placing a guard about the big one and getting an eleventh-hour substitute for the deposed Darracq pilot Hemery was outwitted and the car covered the 2 miles in 58 4/5 seconds, winning the 2-mile-a-minute speed crown. Demogeot was not known to be much of a driver as he was only Hemery’s mechanic. It looked like sure defeat to stack him up against Marriott in the Stanley steamer, which was the holder of the mile straightaway record at that time.

Eight-Cylinder Darracq

Details as to the construction of the car are meager. It had an eight-cylinder engine, the cylinders cast in pairs and set in the form of a V with the apex of the V pointing to the ground. It was credited with 200 horsepower, wire wheels were used and the springs were semi-elliptic in the rear as well as in front. As was the case in most of the cars of that day, the driver was perched very high and at what would seem to be an uncomfortable position, especially for high-speed work. „Whistling Billy“ was the name of the White steamer that Webb Jay used to drive in 1905. It created a 1-mile record at Morris park, doing a mile in 48 3/5 seconds, and won the Thomas cup for the Chicago Automobile Club against the big Fiat driven by Chevrolet and Walter Christie’s 120-horsepower double-engined, direct-drive car, both of which were running under the Automobile Club of America’s colors. Owing to the peculiar construction of the track, which eliminated one or two turns, the mile record did not stand.

This was in July, and a month later the racing career of the White company, Whistling Billy and Webb Jay was ended simultaneously when the car went through the fence at Buffalo, August, 23, almost killing Jay. This caused the retirement from racing of one of the greatest drivers of the early days.

Alfred G. Vanderbilt’s special racing car was the greatest gold brick that ever was perpetrated in this line. Vanderbilt had the speed fever following the success on the mile record by his brother, W. K. Vanderbilt, and decided to build a car that would beat everything at the Ormond meet. He employed an Italian engineer, Sartori, and one or two other foreign experts, who promised unlimited speed. He is said to have spent $60,000 or $70,000 on it and it was taken to the Ormond meet for the January trial in 1906 at the time the Stanley and the Darracq made their records. However, it never got to the tape. It was credited with 250 horsepower, although like many of the others of that day it probably was considerably over-rated.

Christie’s Front Drivers

One of the oddest and oldest of racing creations was the Christie, and still is for that matter, one of them now being driven by Oldfield, who created the present 1-mile dirt track record with it at Bakers- field, Cal., last year. The Christie is not- ed for being a front-drive car and was first exploited by its designer, Walter Christie, who declared that it was easier to pull a car than push it. The feature of the car was that the crankshaft of the engine formed the front axle.

Christie built it in three forms, the two latter, a four-cylinder and an eight-cylinder, both of the V-type. The eight-cylinder car first appeared at the 1905 meet at Morris Park. The four-cylinder was the car used mostly. Its real speed is not known but it is declared to be sensational indeed. Christie drove it at the first Indianapolis meet and since then the old car has been campaigned all over the country. It is now owned by Barney Oldfield.

The original car appeared at Ormond beach in 1904, when it scored 1 mile in 1 minute. The engine had 30 horsepower, and the car weighed 1,272 pounds but was rebuilt during the summer of 1904 so that it showed 40 horsepower and weighed 25 pounds less than before. In this car the engine was a four-cylinder vertical, one casting forming the front of the machine and supporting the full weight of the engine on the axle. The steering also was on the front wheels.

The air-cooled Premier was notable chiefly from the fact that its pilot was Carl Fisher. The engine was a four-cylinder vertical type, and the car was campaigned in 1903 and 1904 about the time that Cedrino, Oldfield, Chevrolet, Jay and Kiser were running around the dirt tracks. Fisher turned up at Ormond beach with his car but did not make any great showing. One peculiarity of the engine was that it was entirely open, the valve timing gears and the magneto drive and so on were not in. closed by a housing of any sort.

This was one of the first cars in America to have a magneto, which was driven by chain from the front end of the engine. The wheelbase was very short, the engine taking up most of the space between front and rear axles. There were no springs at the rear, but the main frame was hung at the front on a cross spring and the engine bolted directly to it. The gears were shifted by a handle like that of a streetcar controller.

Fisher and the Sorrel

Carl Fisher made his first appearance as a motor speed merchant at Dallas, Texas, in 1901. The chief feature of the meet was a 4-mile relay race in which Fisher on a motorcycle was to go against a different horse at every mile. The first horse brought out was a long-legged sorrel which seemed to be puzzled with the situation and in doubt as to what was expected of him. When the word was given, the sorrel sprang away at a fast gait and had Fisher beaten for a furlong, then he noticed that there were no other horses running and it seemed to occur to him that there probably had been a bad start. He stopped, looked over the field and, in spite of the desperate efforts of his jockey, turned around and returned to the post to look for the other horses.

Two other horses then were started and beat the machine a good distance. The sorrel again was started and got off well, but slowed up at the quarter to see what was the matter. He caught a glimpse of the motor and it finally occurred to him what was expected. The sorrel’s indecision was a lucky circumstance for the motorcyclist for when the horse did get started he made a hot race and was beaten by only three lengths.

The Gordon Bennett cup races have made famous a number of cars and drivers. One of these is the Mors which, driven by Gabriel, made a showing at the 1903 Gordon Bennett and finished third in the Paris-to-Madrid race. The 1903 Gordon Bennett in Ireland was won by the Mercedes with Janetzy driving. On account of the burning of the Daimler factory in Germany shortly before the race, the 90-horsepower Mercedes, built especially for the race, were destroyed so Janetzy had to drive a 60-horsepower machine. This had a four-cylinder motor of 5.46 by 5.85 inches. The motor was remarkable chiefly for its inlet valves, which were fitted directly into the top of the cylinder heads and had three separate and distinct seats, so that the area of the combined opening would be equal to a single-seated valve of 8 inches diameter.

Water was circulated through a honeycomb radiator by a centrifugal pump and the mechanism which controlled the change-speed gear was operated by a cam in the gearcase, so that it could be rotated by the backward and forward movement of the controlling lever. Both front and rear axles were of I-beam section. This was remarkable in those days as it was about the first to employ the I-beam type of front axle. The motor was controlled by regulating the lift of the inlet valves through a lever corresponding to the present day throttle on the steering wheel.

Packard Gray Wolf

The Packard Gray Wolf was built during the year 1902 and was raced in 1903 and 1904. Its exterior appearance was quite suggestive of its name. It is a very light car with a sloping hood which came to a point just over the cross- spring which formed the front suspension. The radiator was a series of tubes and fins along the bottom of the hood on either side. The front axle was round section and wire wheels were used. The motor had four cylinders, 4 3/16 by 5 inches and was rated at 24 horsepower. A significant fact about this car was the employment even at that early day of the Packard two-unit construction, the motor and clutch under the hood and the gearset on the rear axle.

American cars did not make any great showing in the 1903 Gordon Bennett race which took place in Ireland. There were three cars that won the preliminary elimination trial in America. Two of these were Wintons and the other was Mooers‘ Peerless. Alexander Winton drove the eight-cylinder Winton Bullet, which has been described. Percy Owen drove the four-cylinder Winton, similar in many respects to the larger car, except that it had only four cylinders and weighed only 1,450 pounds. The cylinders were 5 by 6 inches placed horizontally across the center of the frame of the car with the cylinder heads projecting beyond the side. The cylinders were cast iron with aluminum water jackets. There were no cross braces on the frame, the side bars being connected and held together by the radiator, motor, gear box and rear axle. The carbureter had a small hand-wheel adjustment within easy reach of the operator. The ignition system consisted of a single induction coil and storage battery. The spark plugs projected into a narrow aluminum box on the left side of the car. The flywheel weighed 125 pounds and the motor was rated at 40 horsepower, which was a conservative estimate.

The wheels were 32 inches in diameter, with 4-inch Goodrich tires. The front axle was dropped and the springs mounted on top, while the rear springs were hung below the axle. The frame was of wood with 1/8 inch steel sheathing. The car had two speeds forward and reverse, with a pro- peller shaft connected with a bevel gear drive on the rear axle. On the high speed the drive was direct. The wheelbase was 8 feet 6 inches.

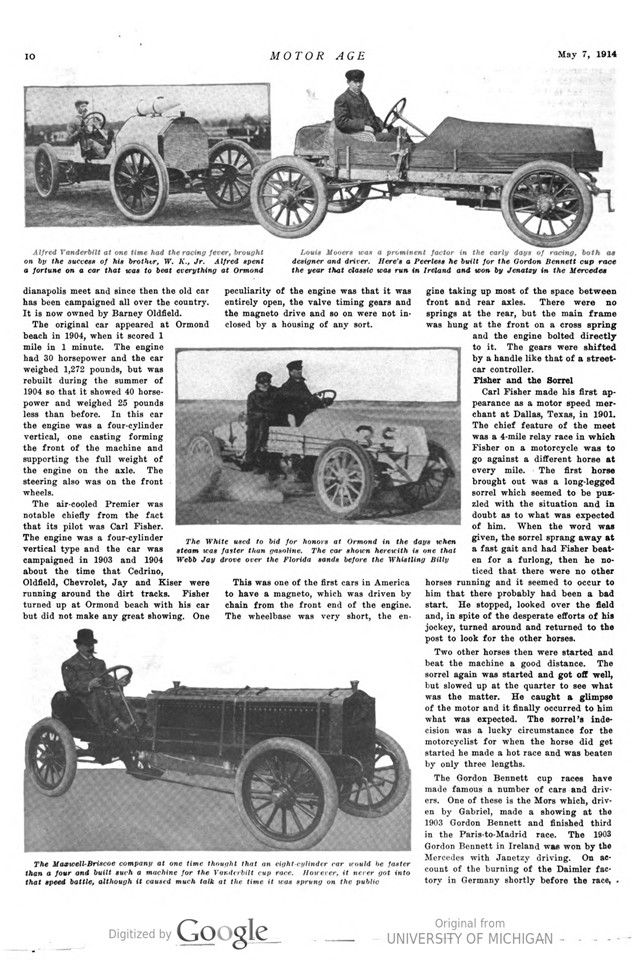

Franklin Skeleton

One of the pioneers of racing in Ameri- ca was the four-cylinder Franklin Skeleton. It was campaigned by E. H. R. Green, who is the son of Hetty Green. He long ago lost his racing enthusiasm, but was one of America’s earliest motor sportsmen. The Franklin had four air-cooled cylinders set vertical and crosswise in the frame and just about the middle of the frame, with the flywheel at the right end of the crankcase. The car was one of the lightest of the racing machines of the old days.

The Peerless which was built by Louis Mooers for the Gordon Bennett race in Ire- land in 1903 and driven by him was somewhat similar to Oldfield’s Green Dragon. It had a four-cylinder vertical motor of 80 horsepower. The cylinders were 6 inches bore and stroke, made of steel 5/16 inch thick with cast iron water jackets and combustion chambers. Two systems of ignition were employed, neither of them magneto. One was a jump-spark placed directly over the inlet valve, and the other a make-and-break igniter. The car had a sliding gearset and a governor in front of the engine. The radiator was one of the features of the car and was made of copper tubes ½ inch in diameter running along the pointed body from the rear axle to the nose. (To be Concluded)

Photo captions.

Page 5.

It’s a far cry from the Ford 999 of 1902 to the English Sunbeam of 1913, but they represent the two extremes. The old 999 was one of our earliest champions, whereas the Sun- beam takes rank as one of the fastest cars of modern days. It holds the 1-hour record of 107 miles 1,672 yards and furthermore it actually has averaged 110.75 miles per hour in a race at Brooklands, surely honors enough to entitle it to claim the world’s speed champion- ship

Page 6.

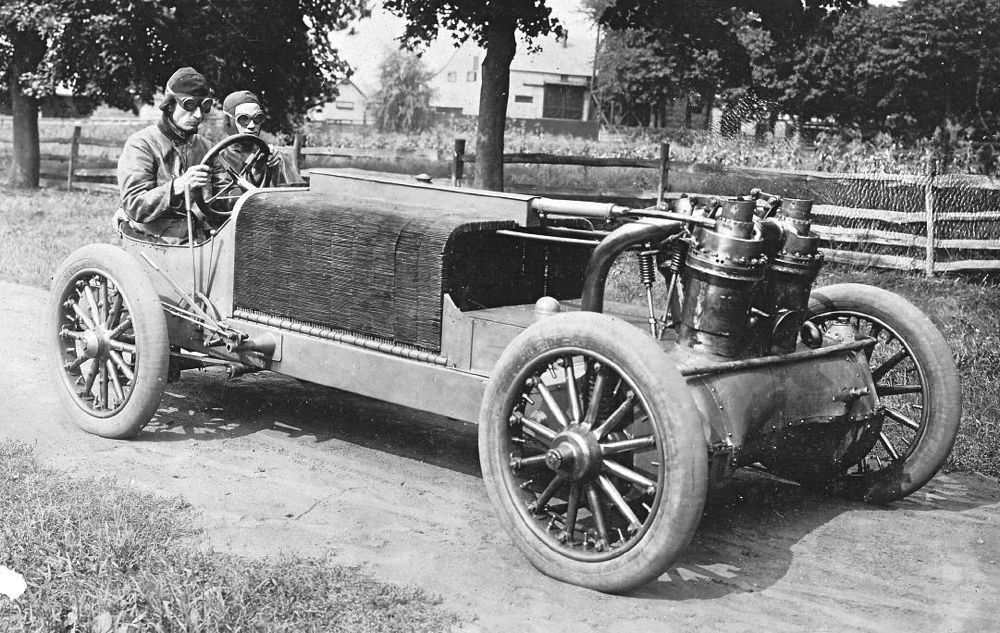

It was in the Peerless Green Dragon that Barney Oldfield established his reputation as a dirt track champion. It was a four-cylinder built by Louis Moers and is said to have had the first underslung frame built in America. There was no gearset, a sliding clutch being used

In the early days at Ormond there was no disputing the speed supremacy of the Stanley steamer, driven by Marriott. It established the world’s straightaway record of 28 1-5 seconds but it met its Waterloo in 1906 when Demogeot in the eight-cylinder Darracq defeated it in the 2-mile-a-minute race.

Page 7.

There were three Winton Bullets, but the one shown herewith was piloted by Earl Kiser, the former bicycle champion. Kiser lost a leg in an accident at Cleveland in 1906 driving this car. Shortly after the Winton company retired from racing, after contesting for several years

The White company also used to support racing and the Whistling Billy was its champion. The car was driven by Webb Jay and created many records. At Buffalo, within a week of the time of the Kiser accident, Jay ran off the track into a pond of water and was injured severely

Page 8.

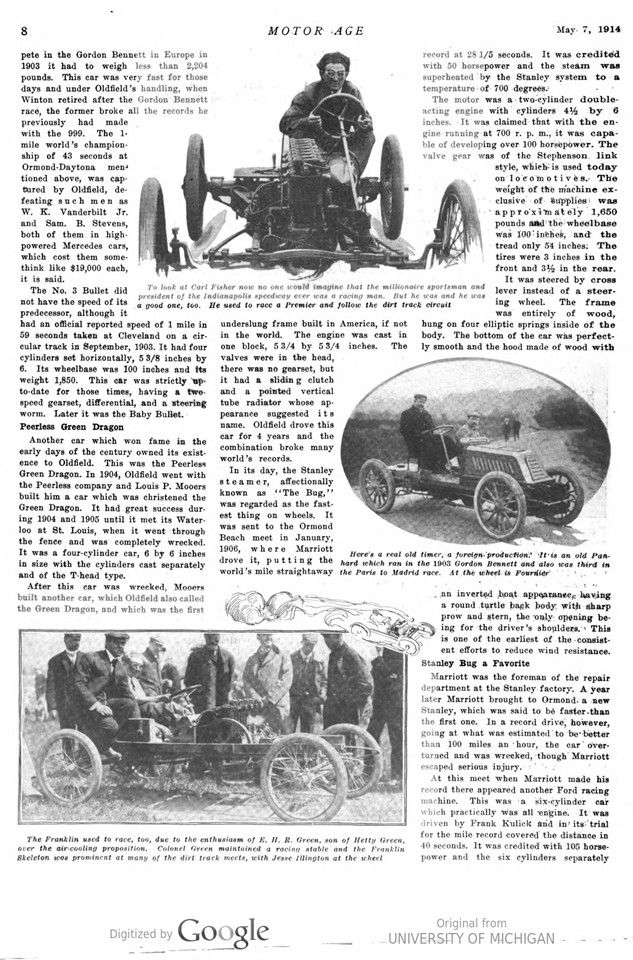

To look at Carl Fisher now no one would imagine that the millionaire sportsman and president of the Indianapolis speedway ever was a racing man. But he was and he was a good one, too. He used to race a Premier and follow the dirt track circuit

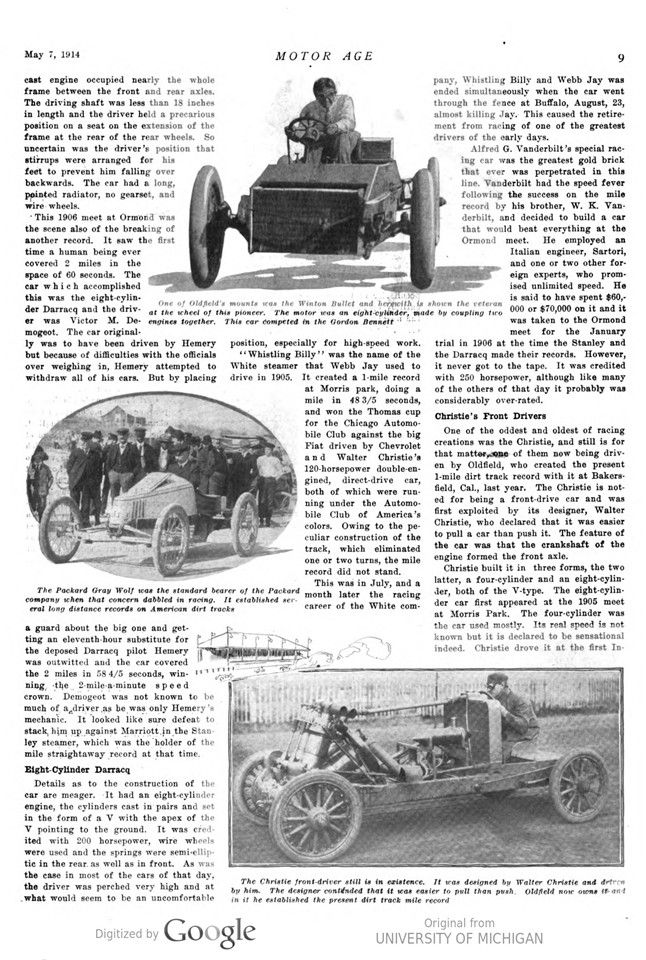

Here’s a real old timer, a foreign production. It is an old Pan- hard which ran in the 1903 Gordon Bennett and also was third in the Paris to Madrid race. At the wheel is Fournier

The Franklin used to race, too, due to the enthusiasm of E. H. R. Green, son of Hetty Green, over the air-cooling proposition. Colonel Green maintained a racing stable and the Franklin Skeleton was prominent at many of the dirt track meets, with Jesse Illington at the wheel

Page 9.

One of Oldfield’s mounts as the Winton Bullet and herewith is shown the veteran at the wheel of this pioneer. The motor was an eight-cylinder, made by coupling two engines together. This car competed in the Gordon Bennett

The Packard Gray Wolf was the standard bearer of the Packard company when that concern dabbled in racing. It established several long distance records on American dirt tracks

The Christie front-driver still is in existence. It was designed by Walter Christie and driven by him. The designer contended that it was easier to pull than push. Oldfield now owns it and in it he established the present dirt track mile record

Page 10.

Alfred Vanderbilt at one time had the racing fever, brought on by the success of his brother, W. K., Jr. Alfred spent a fortune on a car that was to beat everything at Ormond

Louis Mooers was a prominent factor in the early days of racing, both as designer and driver. Here’s a Peerless he built for the Gordon Bennett cup race the year that classic was run in Ireland and won by Jenatzy in the Mercedes

The White used to bid for honors at Ormond in the days when steam was faster than gasoline. The car shown herewith is one that Webb Jay drove over the Florida sands before the Whistling Billy

The Maxwell-Briscoe company at one time thought that an eight-cylinder car would be faster than a four and built such a machine for the Vanderbilt cup race. However, it never got into that speed battle, although it caused much talk at the time it was sprung on the public

Page 11.

Frank Kulick used to drive this six-cylinder Ford, which had a 105-horsepower rating. The driving shaft was less than 18 inches in length and the driver was perched on a seat on the extension of the frame, being held there by means of stirrups. It is said that this big Ford covered a mile in 40 seconds

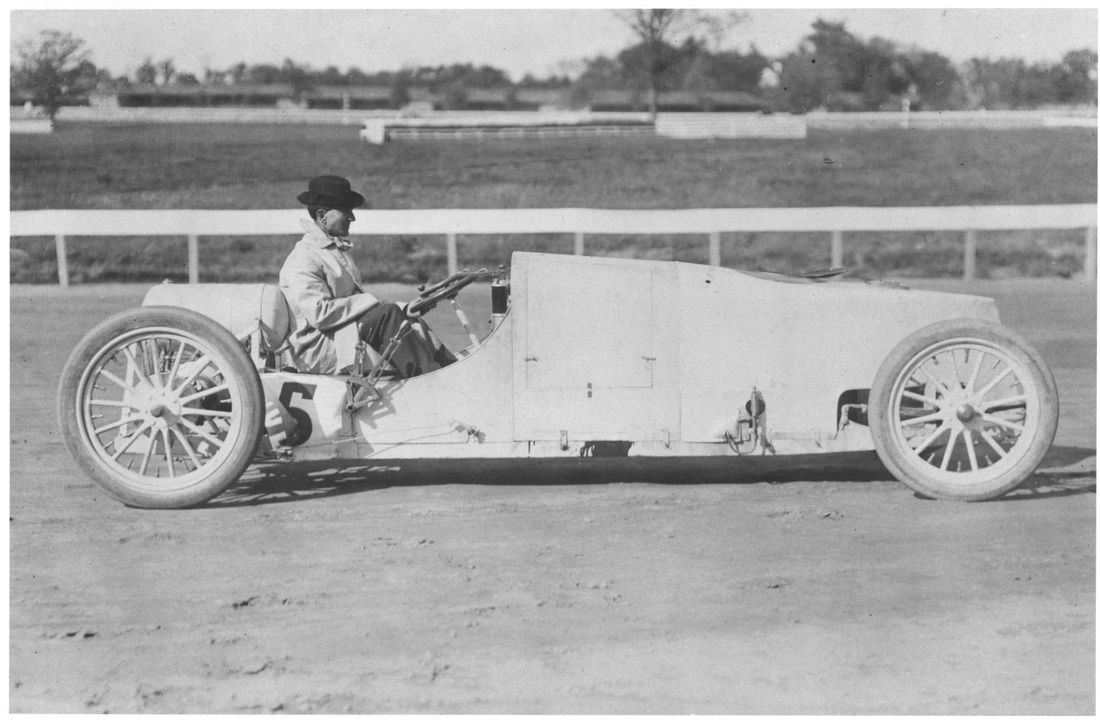

Here’s the old Ford 999 disguised by means of a real streamline body and disked wheels. In appearance it greatly resembles the Stanley steamer, which was one of its great rivals. This particular 999 though was not as much in the limelight as the others

Here’s the Darracq in which Victor Hemery won the second Vanderbilt cup race. It makes an interesting study and shows the trend of design in those early days. Note the short wheelbase and also note how high the driver is from the ground

Camille Jenatzy, the Belgian, now dead, used to drive this old Mercedes, which belongs in the honor base and also note how high the driver is from the ground class, having won the 1903 Gordon Bennett