This report in the June 1913 issue of The Automobile Journal first decribes the most significant marks of the race. But it also highlights the influence of tires, in particular the American Firestone brand, and the durability of important engine parts such as carbureter.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

The AUTOMOBILE JOURNAL – Vol. XXXV, No. 9, June 10, 1913

GOUX TAKES CHIEF SPEEDWAY HONORS.

Wishart Second with Mercer — Spectacular Finish for Merz and Stutz in Third Place—

Race Much Slower Than Last Year — Splendid Driving the Feature.

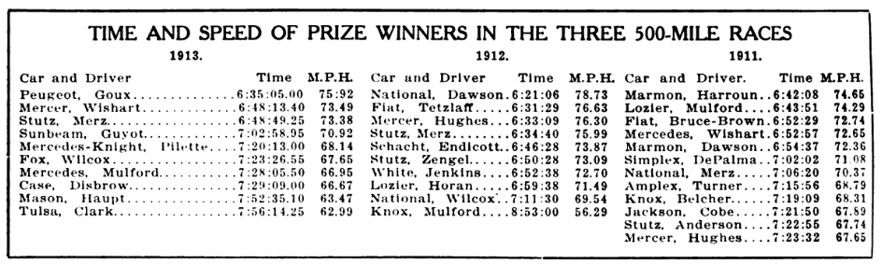

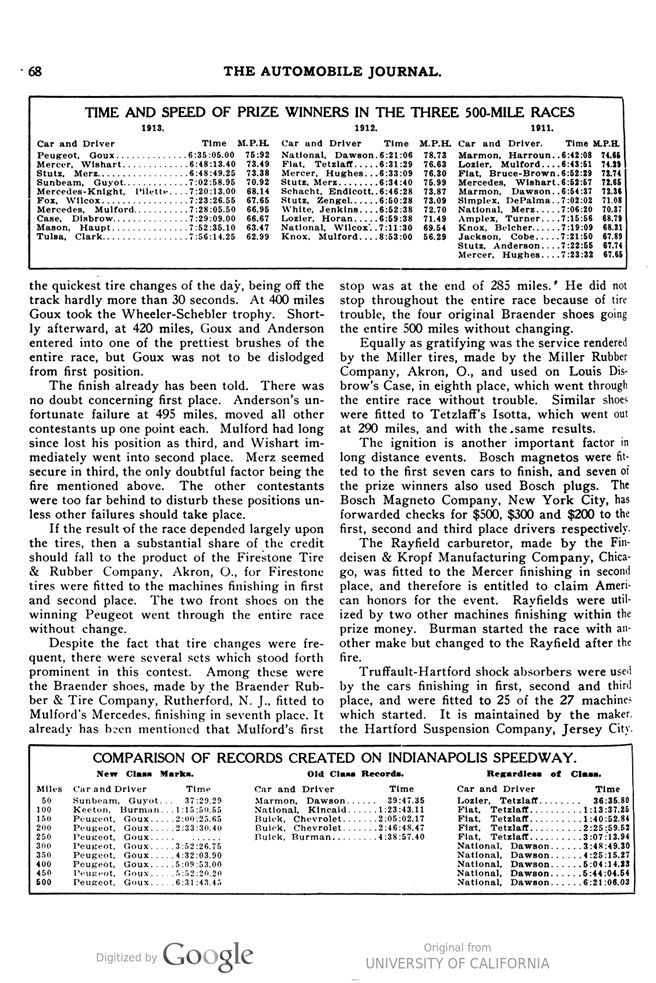

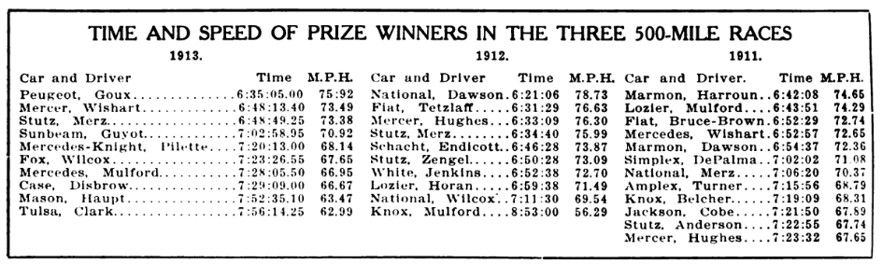

JULES Goux of France, driving a French built Peugeot car, won the third annual international sweepstakes race on the Indianapolis speedway Memorial Day, his speed being 75.92 miles an hour, as against 78.73 for Joseph Daw- son in a National last year and 74.65 for Ray Harroun in a Marmon in 1911. Spencer E. Wishart, in a Mercer, one of the smaller cars in the race, was second, and Charles Merz, in a Stutz, was third. The full list of prize winners is given in tabular form elsewhere, and this table also shows that the first four cars to finish a year ago travelled at faster speed than the winner in this third event.

The result, insofar as determining the winner was concerned, occasioned very little surprise, since the Peugeot has long been regarded as the fastest machine produced abroad, but it was expected that much greater speed would be made. Goux won last year’s Sarthe Grand Prix in France with a car of this make, covering 402 miles of highway at speed of about 73 miles an hour. While Goux is considered one of the best drivers in Europe, his work has been confined almost entirely to road racing, until recently, when he tried out the so-called Indianapolis machine on the Brooklands track, Weybridge, England, covering 106 miles 307 yards in an hour, and creating a new world’s record. It is only fair to state, in this connection, that Goux maintains he was not permitted by his manager to drive his car as fast as he desired, greater speed not being necessary to win the race. And in this comment is found a clue as to the methods used by foreign drivers, Americans being free to exercise their own judgment while at the wheel.

Another element which worked against fast time was the excessive heat. This not only was hard on the tires, tire changes being much more frequent than heretofore, but it had its disastrous effect upon the drivers, several of whom were replaced at intervals by those who had been re- tired from the race and by others who were not scheduled to appear. The fact that the event was limited to cars of not more than 450 cubic inches piston displacement, instead of being a free-for-all as in previous years, probably also was reflected in the final score.

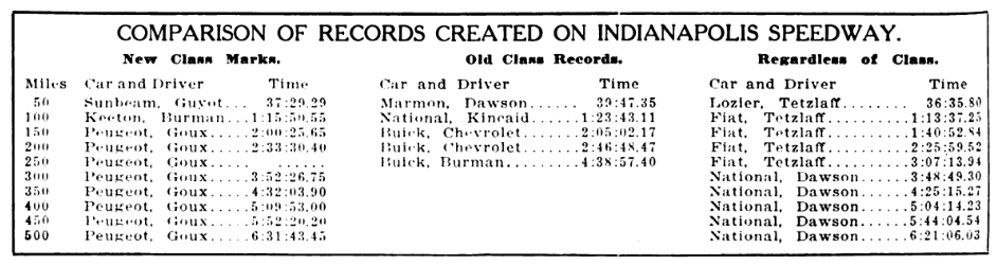

An accompanying table sets forth some of the intermediate times, by which it may be determined that several new class records were established. The free-for-all marks were never endangered, it would appear, and with the exсерtion of that for 50 miles all these were created during the 500-mile event of 1912.

Over 100,000 persons saw the race, according to the statement of the management, and seldom, if ever, has it been possible to witness a better exhibition of generalship in a high speed event. Only one serious accident took place. According to eye witnesses, the Mason, driven by Tower was approaching the west end of the bleachers at a fair rate of speed when one of the front wheels was seen to give way. The car rushed toward the retaining wall and then backed down across the course until it struck the soft earth at the side of the track, where it turned completely over. Tower and his mechanician, Lee Gunning, were thrown out, the former receiving a broken leg and the latter internal injuries. Examination of the machine immediately after the accident failed to disclose the cause.

Twice during the race one of the machines was discovered to be in flames. At 137.5 miles, Burman’s Keeton, which had been showing some of the best speed of the day up to that time, caught fire. He put out the blaze with sand and returned to the pits, losing much valuable time. Later, soon after returning to the track, he was driving beside the Sunbeam, when that car lost a tire. A piece of this casing struck the Keeton’s gasoline tank and thereafter it became necessary to stop the leak with chewing gum, etc., at frequent intervals. Burman and Hugh Hughes, who spelled him at times, managed to keep the car on the track and at the finish it was still running, the only one of the 27 starters which was running and failed to get a prize. Despite these two pieces of hard luck the Keeton gave every evidence of being a splendid machine, and the crowd shared in the disappointment which followed its initial appearance in racing.

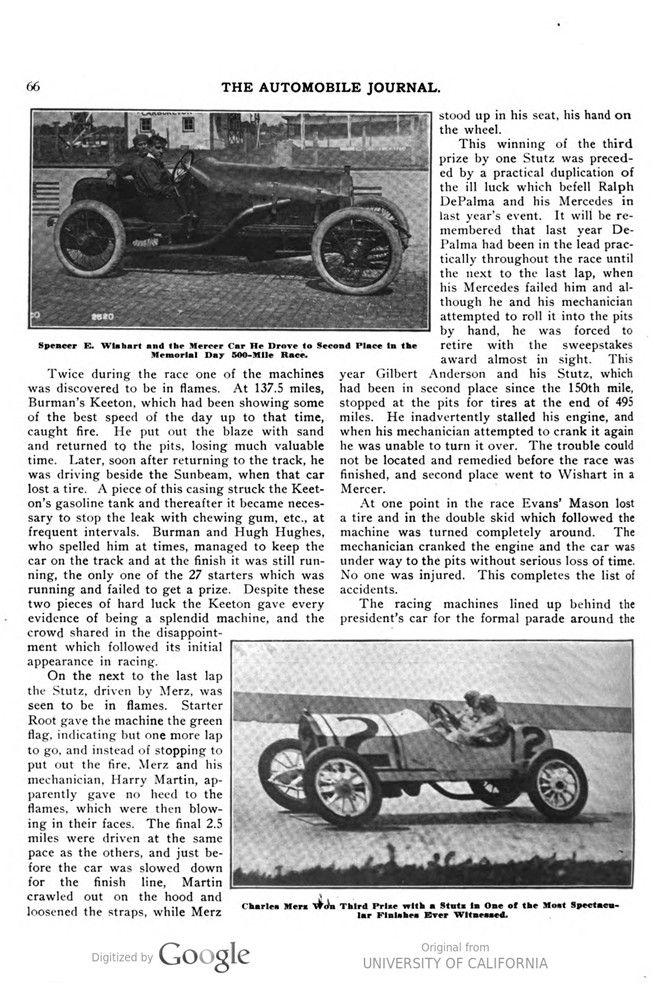

On the next to the last lap the Stutz, driven by Merz, was seen to be in flames. Starter Root gave the machine the green flag, indicating but one more lap to go, and instead of stopping to put out the fire, Merz and his mechanician, Harry Martin, apparently gave no heed to the flames, which were then blowing in their faces. The final 2.5 miles were driven at the same pace as the others, and just before the car was slowed down for the finish line, Martin crawled out on the hood and loosened the straps, while Merz stood up in his seat, his hand on the wheel.

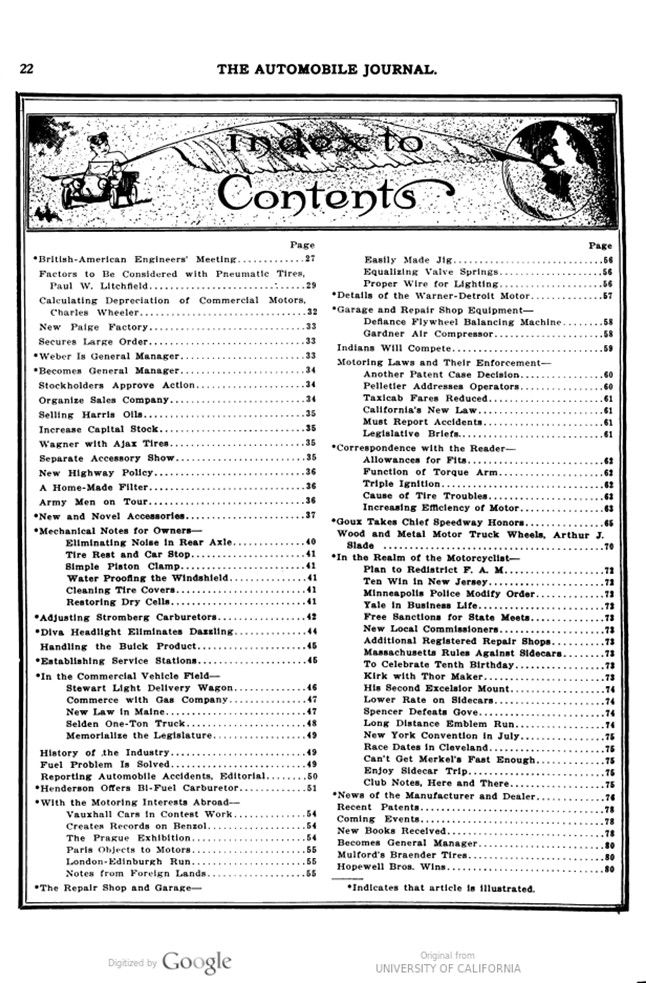

This winning of the third prize by one Stutz was preceded by a practical duplication of the ill luck which befell Ralph DePalma and his Mercedes in last year’s event. It will be remembered that last year De-Palma had been in the lead practically throughout the race until the next to the last lap, when his Mercedes failed him and although he and his mechanician attempted to roll it into the pits by hand, he was forced to retire with the sweepstakes award almost in sight. This year Gilbert Anderson and his Stutz, which had been in second place since the 150th mile, stopped at the pits for tires at the end of 495 miles. He inadvertently stalled his engine, and when his mechanician attempted to crank it again he was unable to turn it over. The trouble could not be located and remedied before the race was finished, and second place went to Wishart in a Mercer.

At one point in the race Evans‘ Mason lost a tire and in the double skid which followed the machine was turned completely around. The mechanician cranked the engine and the car was under way to the pits without serious loss of time. No one was injured. This completes the list of accidents.

The racing machines lined up behind the president’s car for the formal parade around the track and were sent away with a flying start. Evans was the first to complete the initial round of the course, with Goux close behind him and Herr’s Stutz in third place. The second time around Goux was leading Evans, and Clark and the Tulsa had replaced Herr. Evans regained his lead on the third lap, but failed to show up when Goux appeared for the fourth time. Haupt’s Mason took second place at this point.

During Evans‘ temporary retirement Goux came very near lapping him, but the Mason was back on the track just in time. Goux lapped Disbrow and Clark on the seventh round. On the eighth the Schacht made the first stop for tires, and thereafter there was plenty of work for the men in the pits. Goux made his first stop for tires at the end of 25 miles, and Burman took the lead, followed by DePalma’s Mercer, Nikrent’s Case and Haupt’s Mason, in that order.

DePalma’s ill luck appeared to be with him as he was the first to be retired permanently on the 17th lap. Harry Endicott followed him closely. Jenkins and Zucarrelli both were out at the conclusion of 50 miles. At this point Guyot’s Sunbeam was in the lead, his time for the distance being 37:29.29, a new class record.

Burman again took the lead at the end of 60 miles. At 75 he was still leading with Goux and Guyot fighting for second place, and Haupt not far behind the three. At 87.5 miles Nikrent had worked into second place, with Burman leading him by only 30 seconds. At 100 miles it was Burman, Goux and Anderson, with new class record of 1:15:50.55 to Burman’s credit.

Grant was out at 85 miles and his teammate, Trucco, followed him at 90. Later, Grant was in the race for a short time, taking the wheel of the Henderson from Knipper for some little distance. William Endicott went out at 120 miles, when Burman was leading, with Goux, Anderson and Merz behind him. Goux went into first place when Burman’s car took fire but lost his position to Anderson when forced to stop at 140 miles. At 150 miles it was Goux, Anderson, Guyot, Merz and Wishart, with the others making up the field.

Mulford had replaced Merz in fourth position at 200 miles, at which point Goux took the Remy grand brassard and Remy trophy. Mulford’s first stop, and that for gasoline and oil, was made at 285 miles. This was the best showing of any car in the race, and it may be well to add that the machine was the same as that which failed DePalma on the final stretch a year ago.

At 300 miles Goux was the victor of the Prest- O-Lite trophy. Anderson was in second place and Mulford in third. These positions were un- changed at 380 miles, when Merz made one of the quickest tire changes of the day, being off the track hardly more than 30 seconds. At 400 miles Goux took the Wheeler-Schebler trophy. Shortly afterward, at 420 miles, Goux and Anderson entered into one of the prettiest brushes of the entire race, but Goux was not to be dislodged from first position.

The finish already has been told. There was no doubt concerning first place. Anderson’s unfortunate failure at 495 miles, moved all other contestants up one point each. Mulford had long since lost his position as third, and Wishart immediately went into second place. Merz seemed secure in third, the only doubtful factor being the fire mentioned above. The other contestants were too far behind to disturb these positions unless other failures should take place.

If the result of the race depended largely upon the tires, then a substantial share of the credit should fall to the product of the Firestone Tire & Rubber Company, Akron, O., for Firestone tires were fitted to the machines finishing in first and second place. The two front shoes on the winning Peugeot went through the entire race without change.

Despite the fact that tire changes were frequent, there were several sets which stood forth prominent in this contest. Among these were the Braender shoes, made by the Braender Rubber & Tire Company, Rutherford, N. J., fitted to Mulford’s Mercedes, finishing in seventh place. It already has been mentioned that Mulford’s first stop was at the end of 285 miles. He did not stop throughout the entire race because of tire trouble, the four original Braender shoes going the entire 500 miles without changing.

Equally as gratifying was the service rendered by the Miller tires, made by the Miller Rubber Company, Akron, O., and used on Louis Disbrow’s Case, in eighth place, which went through the entire race without trouble. Similar shoes were fitted to Tetzlaff’s Isotta, which went out at 290 miles, and with the same results.

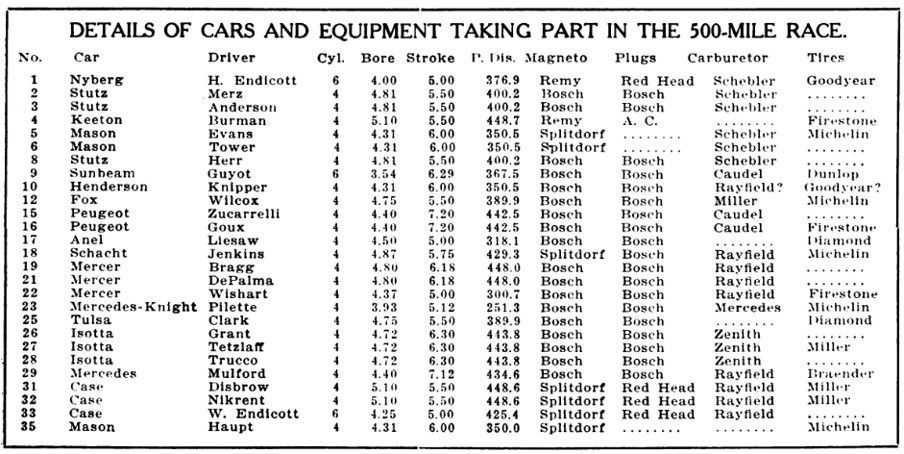

The ignition is another important factor in long distance events. Bosch magnetos were fitted to the first seven cars to finish, and seven of the prize winners also used Bosch plugs. The Bosch Magneto Company, New York City, has forwarded checks for $500, $300 and $200 to the first, second and third place drivers respectively.

The Rayfield carburetor, made by the Findeisen & Kropf Manufacturing Company, Chicago, was fitted to the Mercer finishing in second place, and therefore is entitled to claim American honors for the event. Rayfields were utilized by two other machines finishing within the prize money. Burman started the race with another make but changed to the Rayfield after the fire.

Truffault-Hartford shock absorbers were used by the cars finishing in first, second and third place, and were fitted to 25 of the 27 machines which started. It is maintained by the maker, the Hartford Suspension Company, Jersey City, N. J., that these devices added materially to the comfort and safety of the contestants.

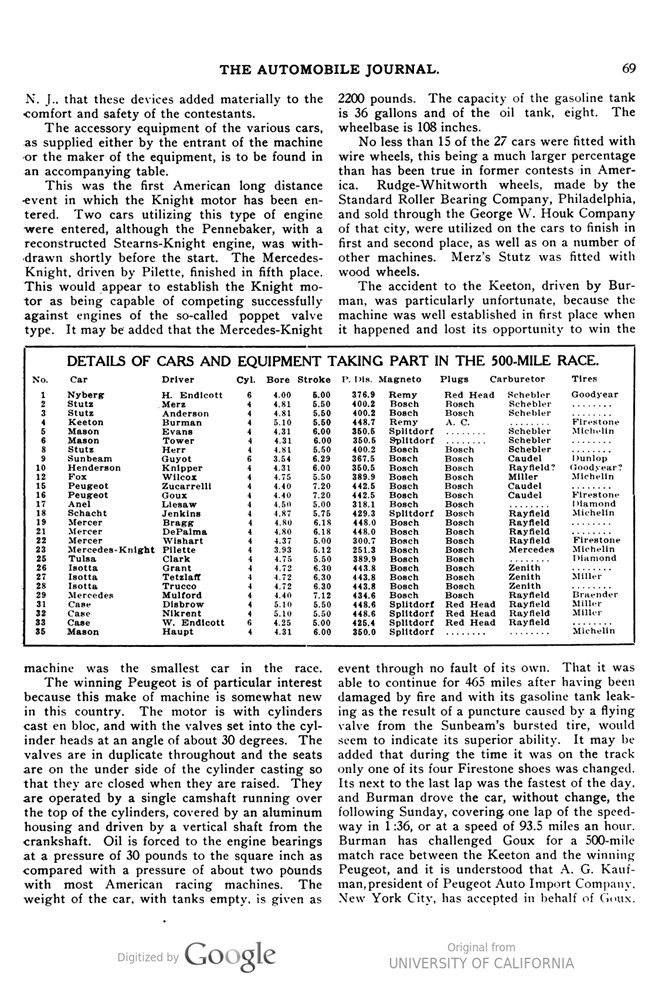

The accessory equipment of the various cars, as supplied either by the entrant of the machine or the maker of the equipment, is to be found in an accompanying table.

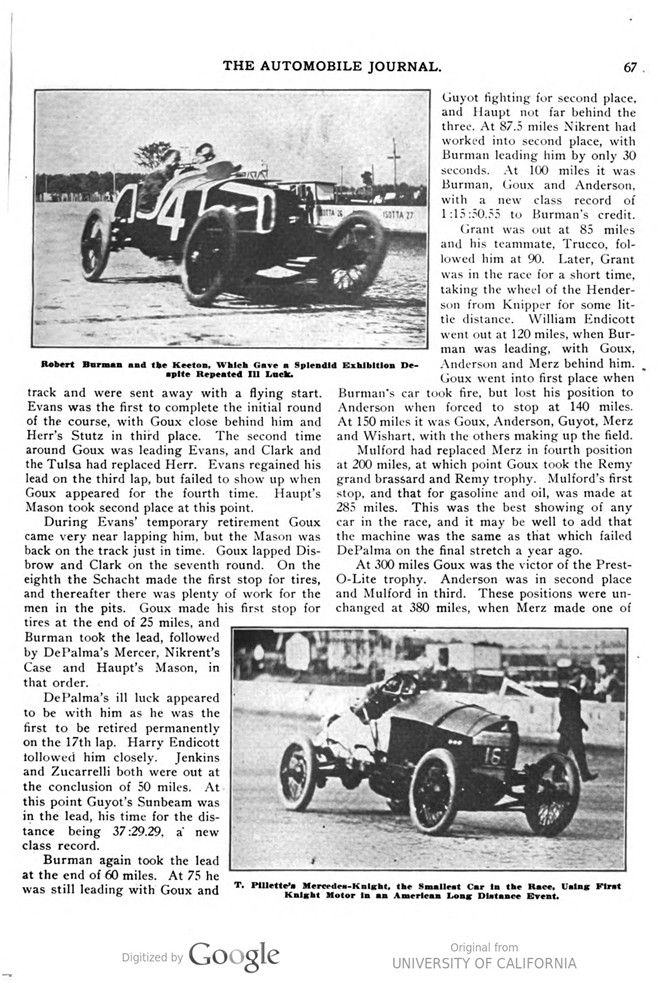

This was the first American long distance event in which the Knight motor has been entered. Two cars utilizing this type of engine were entered, although the Pennebaker, with a reconstructed Stearns-Knight engine, was withdrawn shortly before the start. The Mercedes-Knight, driven by Pilette, finished in fifth place. This would appear to establish the Knight motor as being capable of competing successfully against engines of the so-called poppet valve type. It may be added that the Mercedes-Knight machine was the smallest car in the race. The winning Peugeot is of particular interest because this make of machine is somewhat new in this country. The motor is with cylinders cast en-bloc, and with the valves set into the cylinder heads at an angle of about 30 degrees. The valves are in duplicate throughout and the seats are on the under side of the cylinder casting so that they are closed when they are raised. They are operated by a single camshaft running over the top of the cylinders, covered by an aluminum housing and driven by a vertical shaft from the crankshaft. Oil is forced to the engine bearings at a pressure of 30 pounds to the square inch as compared with a pressure of about two pounds with most American racing machines. The weight of the car, with tanks empty, is given as 2200 pounds. The capacity of the gasoline tank is 36 gallons and of the oil tank, eight. The wheelbase is 108 inches.

No less than 15 of the 27 cars were fitted with wire wheels, this being a much larger percentage than has been true in former contests in America. Rudge-Whitworth wheels, made by the Standard Roller Bearing Company, Philadelphia, and sold through the George W. Houk Company of that city, were utilized on the cars to finish in first and second place, as well as on a number of other machines. Merz’s Stutz was fitted with wood wheels.

The accident to the Keeton, driven by Bur- man, was particularly unfortunate, because the machine was well established in first place when it happened and lost its opportunity to win the event through no fault of its own. That it was able to continue for 465 miles after having been damaged by fire and with its gasoline tank leaking as the result of a puncture caused by a flying valve from the Sunbeam’s bursted tire, would seem to indicate its superior ability. It may be added that during the time it was on the track only one of its four Firestone shoes was changed. Its next to the last lap was the fastest of the day, and Burman drove the car, without change, the following Sunday, covering one lap of the speedway in 1:36, or at a speed of 93.5 miles an hour. Burman has challenged Goux for a 500-mile match race between the Keeton and the winning Peugeot, and it is understood that A. G. Kaufman, president of Peugeot Auto Import Company, New York City, has accepted in behalf of Goux.

Photo captions.

Page 65.

Jules Goux of France and the Peugeot, Winning Combination in the Third Annual International Sweepstakes Event at Indianapolis. – WHEELER & SCHEBLER CARBURETOR

Page 66.

Spencer E. Wishart and the Mercer Car He Drove to Second Place in the Memorial Day 500-Mile Race.

Charles Merz Won Third Prize with a Stutz in One of the Most Spectacular Finishes Ever Witnessed.

Page 67.

Robert Burman and the Keeton, Which Gave a Splendid Exhibition Despite Repeated Ill Luck.

T. Pillette’s Mercedes-Knight, the Smallest Car in the Race, Using First Knight Motor in an American Long Distance Event.

Page 68.

TIME AND SPEED OF PRIZE WINNERS IN THE THREE 500-MILE RACES 1913. 1912. 1911.

COMPARISON OF RECORDS CREATED ON INDIANAPOLIS SPEEDWAY.

New Class Marks. – Old Class Records. – Regardless of Class.

Page 69.

DETAILS OF CARS AND EQUIPMENT TAKING PART IN THE 500-MILE RACE.