Here, a critical article is written on the question of front-wheel drive. Is it really necessary? What are the positive effects and how do these apear in comparison to existing rear-wheel drives? From a standpoint of driving all-day passenger cars in contrats to racing cars. But also in view of designing a car. It may well apear, that independant front-springing of a car may influence it’s behaviour much more than front-drive.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

MoToR, Vol. L (50), September 1928

Front Wheel Drive O.K. or N.G.?

An Analysis of a Much Discussed Form of Automotive Design

By Harold F. Blanchard – Technical Editor of MoToR – (From S. A. E. Journal)

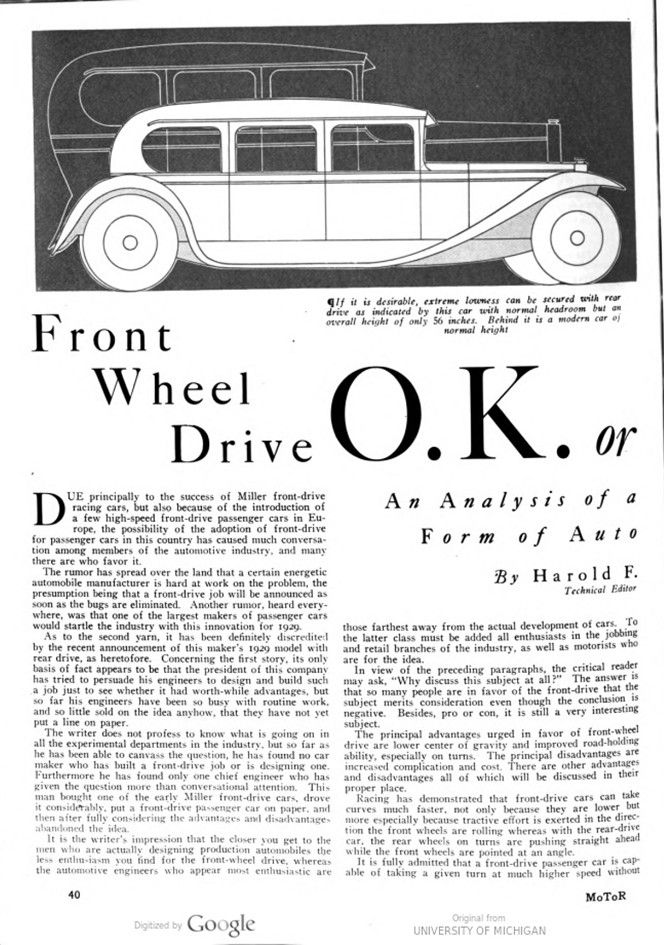

DUE principally to the success of Miller front-drive racing cars, but also because of the introduction of a few high-speed front-drive passenger cars in Europe, the possibility of the adoption of front-drive for passenger cars in this country has caused much conversation among members of the automotive industry, and many there are who favor it.

The rumor has spread over the land that a certain energetic automobile manufacturer is hard at work on the problem, the presumption being that a front-drive job will be announced as soon as the bugs are eliminated. Another rumor, heard everywhere, was that one of the largest makers of passenger cars would startle the industry with this innovation for 1929.

As to the second yarn, it has been definitely discredited by the recent announcement of this maker’s 1929 model with rear drive, as heretofore. Concerning the first story, its only basis of fact appears to be that the president of this company has tried to persuade his engineers to design and build such a job just to see whether it had worth-while advantages, but so far his engineers have been so busy with routine work, and so little sold on the idea anyhow, that they have not yet put a line on paper.

The writer does not profess to know what is going on in all the experimental departments in the industry, but so far as he has been able to canvass the question, he has found no car maker who has built a front-drive job or is designing one. Furthermore, he has found only one chief engineer who has given the question more than conversational attention. This man bought one of the early Miller front-drive cars, drove it considerably, put a front-drive passenger car on paper, and then after fully considering the advantages and disadvantages abandoned the idea.

It is the writer’s impression that the closer you get to the men who are actually designing production automobiles the less enthusiasm you find for the front-wheel drive, whereas the automotive engineers who appear most enthusiastic are those farthest away from the actual development of cars. To the latter class must be added all enthusiasts in the jobbing and retail branches of the industry, as well as motorists who are for the idea.

In view of the preceding paragraphs, the critical reader may ask, “Why discuss this subject at all?“ The answer is that so many people are in favor of the front-drive that the subject merits consideration even though the conclusion is negative. Besides, pro or con, it is still a very interesting subject.

The principal advantages urged in favor of front-wheel drive are lower center of gravity and improved road-holding ability, especially on turns. The principal disadvantages are increased complication and cost. There are other advantages and disadvantages all of which will be discussed in their proper place.

Racing has demonstrated that front-drive cars can take curves much faster, not only because they are lower but more especially because tractive effort is exerted in the direction the front wheels are rolling whereas with the rear-drive car, the rear wheels on turns are pushing straight ahead while the front wheels are pointed at an angle.

It is fully admitted that a front-drive passenger car is capable of taking a given turn at much higher speed without skidding than a rear-drive car of otherwise similar specifications. But what of it? It is the writer’s experience that the modern, well-balanced, well-sprung, reasonably low passenger car can, without skidding, take most turns faster than is safe in view of the fact that hedges, fences and other obstructions prevent seeing the whole turn.

Almost any 1928 automobile can round most hard-surfaced state road bends at 40 to 50 miles per hour without skidding, and in most cases, this is faster than is safe from a visibility standpoint. Would it be any advantage to negotiate these bends at 70 miles per hour? If the answer is „yes,“ then front-drive may be worthwhile.

So far as straightaway driving is concerned it is doubtful whether there is enough advantage in front-drive to make it popular. It is true that if a front-drive job begins to skid it may be pulled out of it by opening the throttle. If skidding is a problem, then front-drive may be worthwhile. For general use it is doubtful whether most car owners could see any advantage in front-drive or distinguish front from rear-drive when behind the wheel.

So far as operation of passenger cars on dry roads is concerned, skidding is mainly caused by severe braking, a quick turn or both, usually to avoid an accident. This appears to be no time to step on it to pull out of a skid. Therefore, if the anti-skid feature can’t be used for the usual skid, this particular front-drive advantage is negligible.

Rule No. 1 in driving a front-drive race car at high speed is not to close the throttle abruptly for fear the front end will change places with the rear end, and Rule 2 is to step on it when the car begins to skid. To take the foot off the throttle abruptly is to court disaster, and it is commonly believed that pulling the foot from the throttle was the cause of at least two bad spills noted race drivers have had this past twelve months in front-drive cars.

The writer does not know whether there would be similar danger in lifting the foot on a front-drive passenger car traveling at the relatively moderate speed of 70 miles per hour. Probably not on dry roads but it does appear that there would be danger in closing the throttle abruptly when running fast on a wet or otherwise slippery road.

That front-drive by itself has little merit for passenger cars is the view of no less an authority than M. de Lavaud, a French engineer, himself a designer of front-drive passenger cars. He says:

“One usually dilates upon the remarkable steadiness and roadability of cars fitted with front-drive. One should note that front-drive is, in principle, associated with independently sprung front wheels. It is precisely that independence and not the fact that the drive is from the front, which produces those unquestionable advantages which have been verified. My opinion is that, apart from a few practical and secondary advantages, the front-wheel drive does not, in itself, produce any real technical benefit.” (The italics are MoToR’s.)

Mr. de Lavaud states the case fairly, in contrast to many front-drive enthusiasts who use the term front-drive as symbol for a certain type of car which has a number of radical features of which front-drive is only one. It isn’t good logic to compare a rear-drive car with conventional springs and axles and normal clearance with a front-drive car without axles and with perhaps six inches clearance. Incidentally the superior riding quality claimed for front-drive machines seems to be entirely due to the independent springing.

Why front-drive and independent springing are so frequently seen on the same car, or why they should be associated in principle is not clear although perhaps the two in combination permit a simpler layout–this point cannot be settled by an is examination of the meagre drawings available.

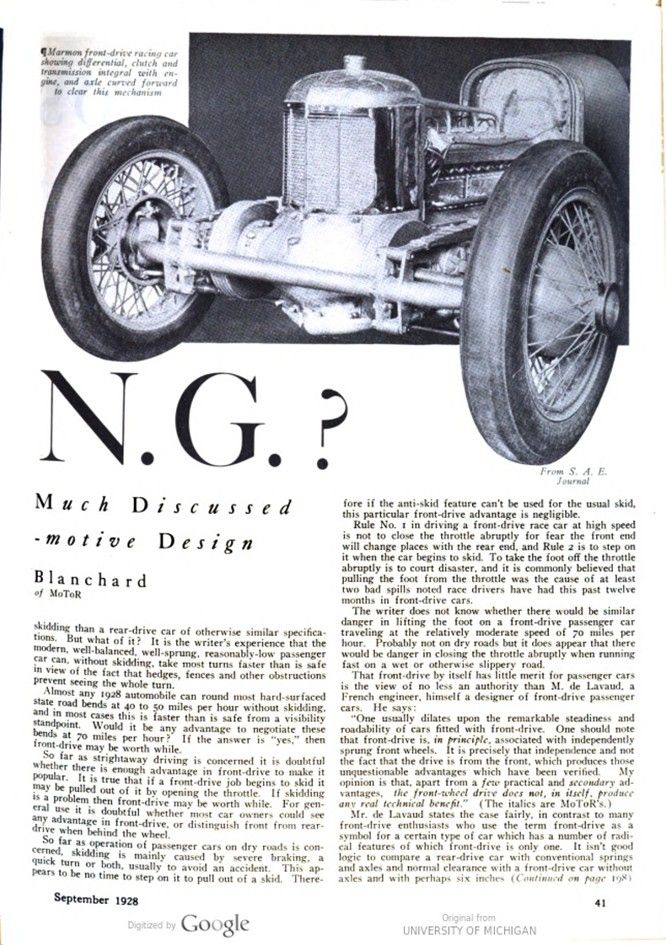

For the benefit of those who are not familiar with front-drive and independent springing this is a good place to explain that in front-drive passenger cars the clutch and transmission are placed ahead of the engine and rigidly attached to a differential, to make a single unit supported on the frame. The axle drive shaft running to each wheel is normally fitted with two universals, the outer one being at the axis of the kingpin. The front wheels may be attached to a bow-shaped axle such as used on Miller and Marmon cars, as shown on page 41, or the axle may be eliminated and the springs mounted on the wheels, Figs. 1, 2 and 3.

With front-drive, the rear axle may be an I-beam with conventional springs, or the rear wheels may also be independently sprung. Fig. 4.

However, the fact should not be overlooked that the same independent springing just described for front-drive cars may also be used for rear-drive cars, in which case the differential housing is mounted on the frame and the drive shaft to each rear wheel is fitted with universals.

The argument as to front-drive versus rear-drive appears to boil down to how low the car of the future must be in order to satisfy the public, and this in turn is mainly a matter of appearance. From the standpoint of safety cars are already low enough. They are also sufficiently low to be beautiful. It is questionable whether lower cars would be fundamentally more attractive. Nevertheless, if the public insists, they must be provided.

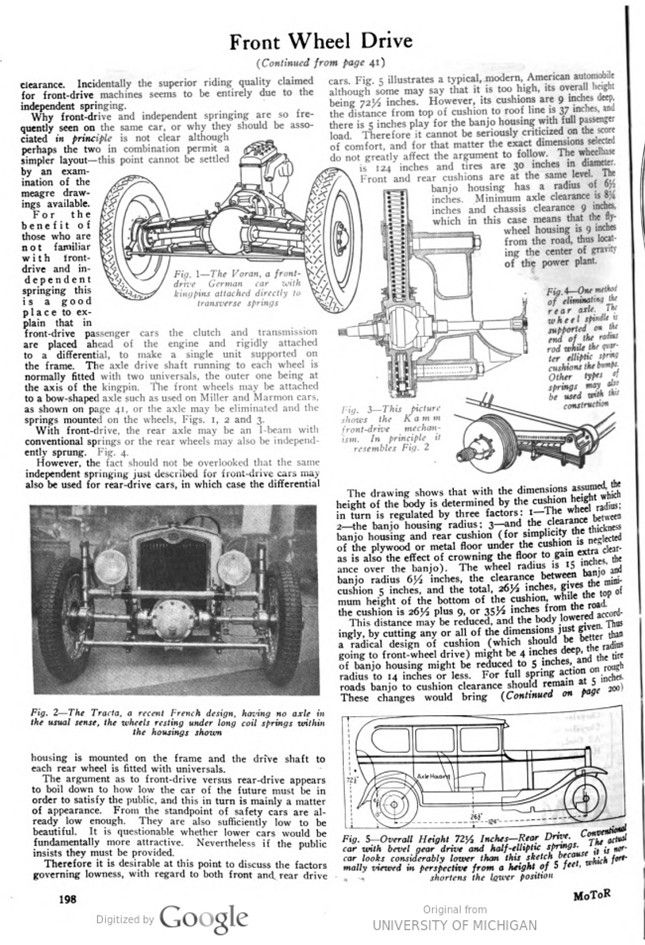

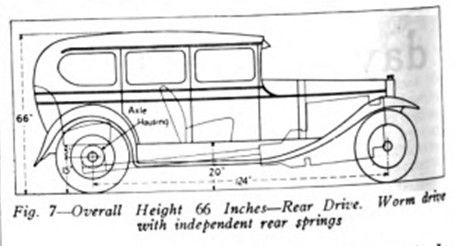

Therefore it is desirable at this point to discuss the factors governing lowness, with regard to both front and rear drive cars. Fig. 5 illustrates a typical, modern, American automobile although some may say that it is too high, its overall height being 72½ inches. However, its cushions are 9 inches deep, the distance from top of cushion to roof line is 37 inches, and there is 5 inches play for the banjo housing with full passenger load. Therefore, it cannot be seriously criticized on the score of comfort, and for that matter the exact dimensions selected do not greatly affect the argument to follow. The wheelbase 124 inches and tires are 30 inches in diameter. Front and rear cushions are at the same level. The banjo housing has a radius of 6½ inches. Minimum axle clearance is 8¼ inches and chassis clearance 9 inches, which in this case means that the flywheel housing is 9 inches from the road, thus locating the center of gravity of the power plant.

The drawing shows that with the dimensions assumed, the height of the body is determined by the cushion height which in turn is regulated by three factors: 1 – The wheel radius; 2 —t he banjo housing radius: 3 — and the clearance between banjo housing and rear cushion (for simplicity the thickness of the plywood or metal floor under the cushion is neglected as is also the effect of crowning the floor to gain extra clearance over the banjo). The wheel radius is 15 inches, the banjo radius 6½ inches, the clearance between banjo and cushion 5 inches, and the total, 26½ inches, gives the minimum height of the bottom of the cushion, while the top of the cushion is 26½ plus 9, or 35½ inches from the road.

This distance may be reduced, and the body lowered accordingly, by cutting any or all of the dimensions just given. Thus, a radical design of cushion (which should be better than going to front-wheel drive) might be 4 inches deep, the radius of banjo housing might be reduced to 5 inches, and the tire radius to 14 inches or less. For full spring action on rough roads banjo to cushion clearance should remain at 5 inches. These changes would bring the top of the cushion 14 plus 5 plus 4 inches, or 23 inches from the road, making the overall height of automobile 23 plus 37 or 60 inches. It should be noted that these reductions would also cut the height of the cars discussed in the following paragraphs.

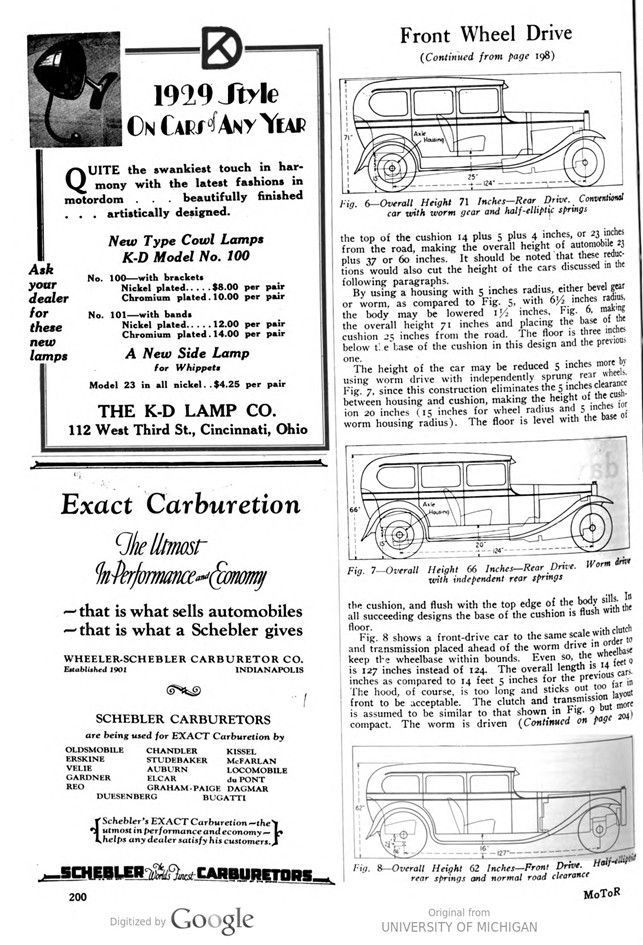

By using a housing with 5 inches radius, either bevel gear or worm, as compared to Fig. 5, with 6½ inches radius, the body may be lowered 1½ inches, Fig. 6, making the overall height 71 inches and placing the base of the cushion 25 inches from the road. The floor is three inches below the base of the cushion in this design and the previous one.

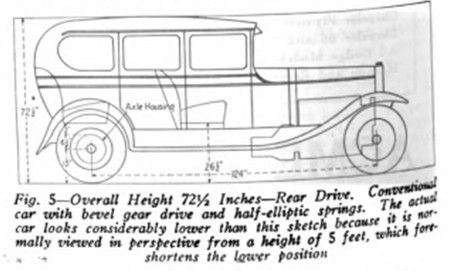

The height of the car may be reduced 5 inches more by using worm drive with independently sprung rear wheels, Fig. 7, since this construction eliminates the 5 inches clearance between housing and cushion, making the height of the cush- ion 20 inches (15 inches for wheel radius and 5 inches for worm housing radius). The floor is level with the base of the cushion, and flush with the top edge of the body sills. In all succeeding designs the base of the cushion is flush with the floor.

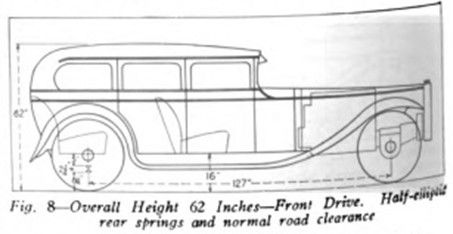

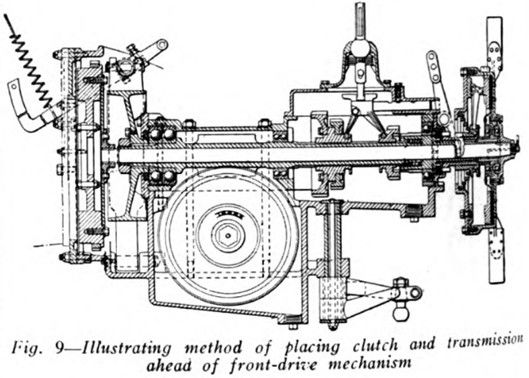

Fig. 8 shows a front-drive car to the same scale with clutch and transmission placed ahead of the worm drive in order to keep the wheelbase within bounds. Even so, the wheelbase is 127 inches instead of 124. The overall length is 14 feet 9 inches as compared to 14 feet 5 inches for the previous cars. The hood, of course, is too long and sticks out too far in front to be acceptable. The clutch and transmission layout is assumed to be similar to that shown in Fig. 9 but more compact. The worm is driven from the transmission by a hollow shaft through which runs a solid shaft connecting the crankshaft to the clutch at the front.

With an I-beam rear axle having a depth of 2¾ inches, the base of the rear cushion rests at a height of 16 inches or 8¼ plus 2¾ plus 5 inches, being respectively axle road clearance, axle depth and clearance between axle and cushion. The overall height is 62 inches. The cushion base is flush with the frame, being 2 inches below the body sills. Cushion height could be reduced 7¾ inches more by using independent springing, thus making the overall height 54¼.

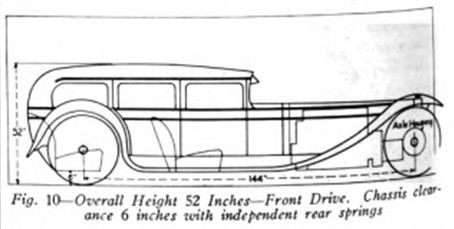

In all the cases so far considered, minimum axle clearance has been 8¼ inches, and minimum chassis clearance has been 9 inches. However, if greater lowness is desired chassis road clearance must be sacrificed, as shown in Fig. 10, where the clearance is 6 inches. Clutch and transmission are placed to the rear of the differential and thus add 20 inches to the wheelbase, making it 144 inches, and producing an ungainly-looking hood. Hypoid bevel gearing (with the pinion off-center) is used since the axis of the crankshaft is below the axis of the wheels. To raise the engine would probably reduce the driver’s vision too much, although the engine could be tilted to permit worm drive or spiral bevel.

With independent rear springing, the base of the cushion is set 6 inches from the road, thus making the overall height 52 inches. The floor is 8 inches below the tops of the sills.

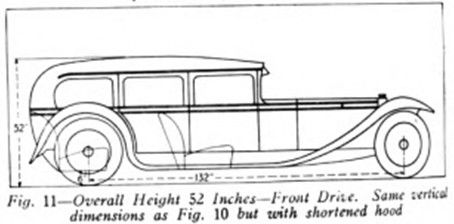

By using a special transmission as well as making all other possible compromises it is probable that the wheelbase increase due to front-drive may be limited to 8 inches, making it 132 inches, as shown in Fig. 11. For the sake of appearance, wheels have been reduced to 28 inches and the radiator set back. The vertical dimensions are the same as before. The car is undeniably smart, but as stated previously, it is doubtful whether it is worth while going to all this trouble to obtain this particular kind of smartness.

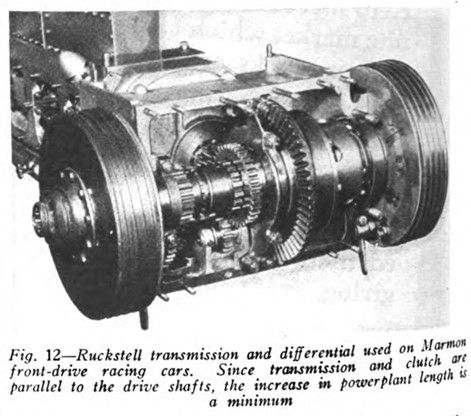

The main items of trouble and expense in obtaining this low car are: 1 – Squeezing the powerplant to reduce its length 12 inches so that the wheelbase will only be increased 8 inches, the reduction being partly secured by a special transmission prob- ably placed in line with the wheel drive shafts as shown in Fig. 12. 2 – The complication of driving and steering through the front wheels, including four universals in place of two for rear drive. 3 – Increase of wheelbase to 132 inches. 4 – Independent springing of all four wheels.

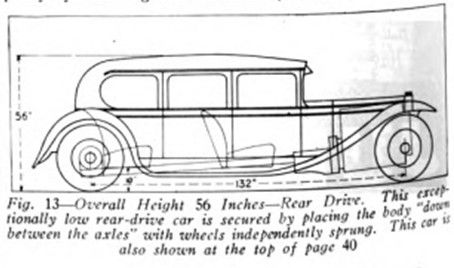

A rear-drive car, Fig. 13, may be obtained with an overall height of only 56 inches by making compromises which seem to be less expensive, less complicated and on the whole, more desirable than those for the front-drive car. Beginning with a wheelbase of 132 inches, by shortening the engine and using an underslung worm with independently sprung wheels, the rear cushion may be set down ahead of the rear axle, thus making the cushion height 10 inches.

The body, of course, has been moved forward 18 inches as compared to the other rear-drive designs yet leg room is unchanged in the rear compartment and is only slightly different in the front compartment. Eight of the 18 inches is made up by the wheelbase increase from 124 to 132 inches, the remainder is partly secured by using a small diameter clutch, partly by removing the vibration dampener from the front of the engine to one of the crankshaft cheeks, and partly by eliminating the radiator from its usual position and allowing the front of the engine to come right up to an imitation radiator The radia- screen which finishes off the front of the car. tor may be put anywhere room can be found for it, probably at the side of the engine. The front axle is curved forward to clear the radiator as on the Marmon front-drive job. The transmission sticks up out of the center of the driver’s compartment while the drive shaft also is in evidence in the rear compartment, but are these objections as serious as the extra complication of front wheel drive?

There are a number of points concerning front-drive which are frequently brought up which will only be discussed very briefly as they appear to be of minor importance, as follows: 1 – Greater accessibility-a doubtful claim; 2 – Reduced life of universals due to transmitting axle shaft torque instead of propellor shaft torque, and due to greater average angularity – the success of front-drives in use appear to answer these criticisms. 3 – Greater damage in case of collision-doubtful claim. 4 – Greater noise, since sound from transmission and differential is carried back – true, but perhaps will not prove objectionable if proper precautions are taken. 5 – Reduced traction up hill – not true. The weight distribution of an automobile is just the same on a grade as on the level. That is, if the weight distribution on the level is 40 per cent front and 60 per cent rear, the same weight distribution holds on a hill. Similarly there are other minor advantages and disadvantages which cannot be discussed because of space.

Summing the question up, the various designs give the following overall heights arranged from high to low:

A – Conventional rear drive with bevel gear, Fig. 5, 72 1/2 inches.

B – Conventional rear drive with worm gear, Fig. 6, 71 inches.

C – Worm rear drive with independent rear springs, Fig. 7, 66 inches.

D – Front-drive with I-beam rear axle and 9-inch chassis clearance, Fig. 8, 62 inches.

E – Rear drive with reduced vertical dimensions (not illustrated), 60 inches.

F – Rear worm drive with independent springs and body set forward, Fig. 13, 56 inches.

G – Front-drive with independent springs and 6-inch chassis clearance, Figs. 10 and 11, 52 inches.

While it is doubtful that lower cars are desirable, if they are wanted it is evident that by making suitable compromises adequately low cars may be secured with rear-drive as indicated by E and F, and it seems clear that very low rear-drive cars may be secured with less expense and complication than through the use of the front drive.

Photo captions.

Page 40 – 41.

If it is desirable, extreme lowness can be secured with rear drive as indicated by this car with normal headroom but an overall height of only 56 inches. Behind it is a modern car of normal height

Marmon front-drive racing car showing differential, clutch and transmission integral with engine, and axle curved forward to clear this mechanism.

Fig. 1—The Voran, a front-drive German car with kingpins attached directly to transverse springs.

Fig. 2—The Tracta, a recent French design, having no axle in the usual sense, the wheels resting under long coil springs within the housings shown.

Fig. 3—This picture shows the Kamm front-drive mechanism. In principle it resembles Fig. 2

Fig.4 – One method of eliminating the wheel spindle is supported on the end of the radius rod while the quarter elliptic spring cushions the bumps. Other types of springs may also be used with this construction.

Fig. 5—Overall Height 72½ Inches-Rear Drive. Conventional car with bevel gear drive and half-elliptic springs. The actual car looks considerably lower than this sketch because it is normally viewed in perspective from a height of 5 feet, which fore-shortens the lower position

Fig. 6 – Oerall Height 71 Inches – Rear Drive. Conventional car with worm gear and half-elliptic springs

Fig. 7 – Overall Height 66 Inches – Rear Drive. Worm drive with independent rear springs

Fig. 8 – Overall Height 62 Inches-Front Drive. Half-elliptic rear springs and normal road clearance

Fig. 9 – Illustrating method of placing clutch and transmission ahead of front-drive mechanism

Fig. 10 – Overall Height 52 Inches-Front Drive. Chassis clearance 6 inches with independent rear springs

Fig. 11 – Overall Height 52 Inches-Front Drive. Same vertical dimensions as Fig. 10 but with shortened hood

Fig. 12 – Ruckstell transmission and differential used on Marmon front-drive racing cars. Since transmission and clutch are parallel to the drive shafts, the increase in powerplant length is a minimum

Fig. 13 – Overall Height 56 Inches-Rear Drive. This exceptionally low rear-drive car is secured by placing the body down also shown at the top of page 40