This article contains a very extensive description of the race and very few pictures. So scratch yourself to get in for a long read ( when you’re interested, of course) !

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

MOTOR AGE Vol. XXVII, No. 22 Chicago, June 3, 1915 $3.00 Per Year

Ralph DePalma Wins Indianapolis Classic in Record Time

By J. C. Burton

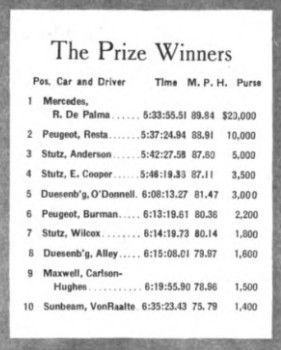

INDIANAPOLIS, Ind., May 31 – Special telegram – Ralph de Palma, a hero in defeat 3 years ago, was a hero in victory at the Indianapolis motor speedway this afternoon. At the wheel of a Mercedes, the Italian proved that he, not fate, was the master of his destiny by winning the fifth annual international sweepstakes in the undreamed-of time of 5 hours 33 minutes 55.5 seconds. His average for the 500 miles, 89.84 miles an hour, shatters to bits the record of 82.47 miles per hour, established last year by Rene Thomas, the French driver who swept to victory in a Delage.

De Palma’s victory was a hyphenated triumph. He is a native of sunny Italy but a naturalized citizen of the United States and his car is of German extraction. Consequently, international complications resulted from his feat. If there is any truth in the cable reports from across the Atlantic, the realm of Garibaldi and the faderland are now at war and the alliance of the Italian speed king and the German space destroyer is without knowledge or sanction of either the king of the Latins or the kaiser of the Teutons.

De Palma’s battle was not alone against the cars that roared a challenge at the Mercedes. His old jinx rode with him and threatened to rob him of victory as it did in 1912 when with only three more laps to go and his triumph generally conceded, the motor of the Italian’s car rebelled. The engine of the Mercedes balked today when the Italian was but 5 miles from his goal. A connecting rod broke and punched a hole in the crankcase. One cylinder was missing when the green flag waved from the starter’s bridge and as de Palma was hailed as victor, oil was pouring from the grease pan. Had he been forced to make another circuit of the oval, the tragedy of 1912 might have been repeated and de Palma would have been pitied, not crowned.

Four Cars Shatter Record

The achievement of shattering Thomas‘ 1914 record is shared by three drivers other than de Palma for the three cars that trailed the Mercedes over the wire – Resta’s Peugeot and two of the Stutz entries – averaged better than 82.47 miles per hour.

France was unable to duplicate its triumphs of 1913 and 1914, when Jules Goux and Rene Thomas humbled the champions of America on the Hoosier saucer of speed, but the Gauls took the highest consolation honors of the day when Dario Resta, another driver of Latin lineage and the monarch of the Panama-Pacific exposition course by virtue of dual victories in the Vanderbilt and grand prize races of 1915, captured second place in a Peugeot. In fact, today’s classic was a feud between two Italians, a wop wrangle, a guerre de guinea, as the French might express it. The two swarthy-skinned descendants of Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome, monopolized the spot- light in the most spectacular hood-to-hood and wheel-to-wheel battle ever fought on the bricks of Carl Fisher’s colossal oval and within the modern circus maximus.

Stutz, on whose cylinders was thrown the Homeric task of putting an Indianapolis- made car in front and duplicating the tri- umph of Ray Harroun’s Marmon in 1911 and Joe Dawson’s National in 1912, had to be content with the team honors of the day. The achievement of Stutz was most notable and praise-deserving despite the fact that its entries were forced to ac- knowledge the supremacy of Mercedes and Peugeot. Stutz started three cars and all three finished inside the money, an unprecedented feat in this country and only equaled in Europe where Mercedes finished three cars in the 1914 French grand prix. Gil Anderson took third place; Earl Cooper was fourth and Howdy Wilcox managed to limp in on two cylinders and captured seventh.

Duesenburg, the second American team of three cars in today’s race, finished two, Eddie O’Donnell taking fifth money and Tom Alley putting his mount in eighth place after a closely contested fight with Wilcox’s Stutz.

For the first time in his career on the Hoosier bricks, Bob Burman managed to complete the entire 500 miles without pounding his car to pieces or wrecking his mount by dare-devil driving.

Hughie Hughes, who relieved Billy Carlson at the wheel of the No. 19 Maxwell, also has a check to show for his labor as the Englishman annexed ninth money because of his persistence. The only other driver to harvest a crop of kale seeds from the bricks was a foreigner, Noel Von Raalte, who took tenth place with the English Sunbeam recently sent across the Atlantic by the British factory for an American campaign.

Emden Trails Far Behind

One other car was running when the race was called. The also ran was the Emden, namesake of the German sea rover. Developed among the corn fields of Iowa, it failed to show the speed necessary to make it a serious contender but Willie Haupt, its driver, refused to quit and trailed far behind the leaders without hope of gaining any pecuniary reward for his patience and tenacity.

Although thirteen of the twenty-four starters were eliminated before the race was completed, the showing made by the 300-inch cars in their first competitive test in America was most praiseworthy. At the end of 250 miles, only four cars were out, three because of mechanical ills and the other being disqualified for infraction of the rules.

The first car to be permanently docked was the Purcell-Cino, the thirteenth being its unlucky lap and a split pump gear eliminating it from competition. The Bugatti was the next machine to fall by the wayside, George Hill abandoning it in disgust on the twenty-third lap when a connecting rod broke. The Bugatti was one of the two cars injured in practice after it had qualified and it did not respond to the first-aid treatment administered. The other recuperating car, the Delage which Rene Thomas drove to victory last year and today in charge of John de Palma, also had not recovered sufficiently from its ailments to stand the strain of the gruelling pace set by Brother Ralph and Resta and was left to its fate on the grass of the infield when a flywheel worked loose on the forty-fourth lap.

The Mais Special was the car to court the displeasure of the officials and to suf- fer the penalty for failure to behave as a racing car should in fast company.

Johnny Mais overran his pit when com- ing in to adjust a flooding carbureter, and misunderstanding the rules ran his car around the road back of the pits to his station, instead of backing to it. This leaving the course automatically disquali- fied the car.

After the half-way post had been passed by the flying leaders, several of the cars showed that they lacked the stamina to withstand the awful punishment of the 90- mile an hour pace. The diminutive Corne- lian, the baby of the race, broke a valve after turning seventy-seven laps and its nurse, the veteran, Louis Chevrolet, retired it. Rickenbacher watched the chase for $50,000 in prize money from his pit after giving promise of being a most dangerous contender for the first 250 miles. His Max- well could not stand the gaff, however, and went out with a broken crankcase on the one hundred and second lap. Engine trouble caused the elimination of Bab- cock’s Peugeot after it had completed one hundred and seventeen circuits of the oval.

Ralph Mulford, who usually carries away some of the prize money in the Memorial Day classic, was not so fortunate today, a broken connecting rod on his Duesenberg transforming him from a participant to a spectator on the one hundredth and twenty- fourth lap.

Porporato, the Italian who crossed the Atlantic to duplicate the victories of Goux and Thomas, had his dream of new worlds conquered shattered when a connecting rod on the Sunbeam broke. The obese alien abandoned the race on the one hundred and sixty-fifth lap when fifth place or better, was generally conceded him.

Klein’s Gameness for Naught

Art Klein was another driver who toiled without reward today. The driver of the Kleinart had a job of work to do from the sixty-eighth lap on. The connection between the oil and gas tanks gave way, causing the lubricant and fuel to mix. After a futile attempt to repair the in- jury, Klein ordered his mechanic to feed the oil by hand and gamely resumed the chase of the unattainable leaders. He finally was ordered off the course for excessive smoke.

Joe Cooper, driver of the Sebring, also sweated in vain. He stopped at his pits eight times to replace spark plugs but his mount refused to respond to the heroic treatment administered and finally showed its ingratitude on the one hundred and fifty-seventh lap by running off the track and disintegrating in the resultant spill. Neither Cooper, or his mechanician were hurt but the car lost a wheel.

Orr’s Maxwell gave up the ghost on the one hundred and sixty-ninth lap when Billy Carlson was at the wheel, vice the former loop-the-loop artiste of sawdust memory. A rear axle gave way, and Carlson spent the remainder of the afternoon wishing that he had the patience of Job and nursing a carbuncle on the back of his neck.

Harry Grant was the last driver to abandon the hopeless pursuit of the fleet Italians. His six-cylinder Sunbeam gave the Vanderbilt cup veteran a lot of trouble. The spark plugs fouled and the clutch refused to hold and Harry decided that the honor of being classed among the also rans was not worth the effort of attempting to finish in his disabled mount.

Fast Pace a Surprise

A record for 500 miles of 89.84 miles an hour, a mark so close to 90 miles an hour that the difference seems infinitesimal, was a surprise to even the wisest of the rail- birds who prophesied that Thomas‘ time of 1914 would be eclipsed by the winner of the 1915 classic. Their guess, however, was about 85 miles an hour and none of them can holler „I told you so,“ tonight.

The phenomenal time is not unexplainable, however. The track was as cool as the proverbial cu- cumber or the frigid mother-in-law who did not favor her daughter’s choice of a husband. In previous races, the sun has beat down upon the bricks and caused havoc with tires. Not so today. Fewer casings were burned up than ever be- fore and the smell of burning rubber was an odor unsensed by the nasal organs of the spectators.

For the first time in the history of the international sweepstakes, dark and lowering clouds hung precariously over the speedway when the cars and drivers lined up for the epochal battle of cylinders. A few drops of rain fell at 9 o’clock and three of the pilots – Burman, Porporato and Hill – donned rubber slickers but such precautions proved unnecessary as the sky leakage was of such short duration that not a single umbrella was raised. By noon, the clouds had cleared away and the sun peeked timidly out from its place of temporary exile. Gradually the celestial illuminating plant generated more power and shed a welcome glow over the crowd, but it was not hot enough to heat the bricks to any noticeable extent.

Since the dawn of the sunless morning, promoters and participants had been on their prayer rugs beseeching J. Pluv to behave himself and reform after a 7-day debauch. Their pleadings were heeded. There was no rain after the starting bomb exploded. A moist wind that blew across the scene of the speed spectacle was chilling and spectators patted themselves on the back for their providence in bringing overcoats and sweaters with them rather than palm leaf fans and sunglasses.

The low temperature for a day so late in May, the timidity of the sun and the drenching that the speedway received in the past week all combined to make the track cool and the prediction was common long before the start that tires would last twice as long today as they did in 1913 or 1914 when spectators acquired a refulgent coat of sunburn and the bricks were so hot that rubber was burned up in a manner truly satanic.

De Palma drove a wonderful race. He always does, but today he proved himself a past master at winning a contest before it is run. He had his race planned. He drove it according to Hoyle. Although his Mercedes did not look to be as fast as the Peugeot, the car of his most dangerous rival, Resta, its velocity was sufficient to bother the Anglo-Italian and finally break his nerve. In his two hundred circuits of the oval, de Palma stopped but twice. His first halt was at the completion of the sixty-third lap when he changed two right wheels in 1 minute. He was running in second place at the time but was so close to Resta, the pacemaker, that the proverbial blanket, which the tout of the horse- racing circuit talks about, would have covered them.

De Palma Springs Coup

The Italian’s other stop was at the end of 300 miles. De Palma changed all four wheels and took on gasoline and oil. This was a move that he had planned. He figured that with his tanks full and new tires all around he would be able to complete the remaining 200 miles without another stop. He lost 2 minutes and 21 seconds and the lead in this maneuver, but it was time well spent for seventeen laps later, Resta was forced to come in for a rear tire and the Mercedes then shot to the front never to be overtaken.

Resta Does Round-Robin

When de Palma stopped at his pits the second time, he sensed that Resta soon would have to follow his example. As the Peugeot passed him, he called the attention of his pitmen to the right rear tire on the French car and then started in pursuit of the Gallic creation. He drove desperately. He was hounding his rival, getting, his goat in the vernacular of the streets, and he succeeded. When the invader from England finally came to a stop, he was so excited that he walked three times around his car like a superstitious poker player who circles his chair thrice in order to break a bad run of luck.

The feud between the two Italians, Resta and de Palma, was bitter and spectacular. Such enmity, the settlement of personal grievances, seems al- most out of place at a time when Italia is calling upon her sons to fight for home and country. But the rivalry between the two was not to be sidetracked and the battle for the lead proved more than thrilling.

Resta was always watching de Palma and de Palma was always watching Resta. They respected one another and made of the con- test a match race. Here were two masters fighting for supremacy. Neither would bend the knee to the other’s daring and skill.

Latins to the Front

At the start of the race, when Wilcox and Anderson alternated in the lead for the first 80 miles and gave promise of putting an American car in front, the two Italians were content to lay back in second and third positions. Resta had the advantage if a two-car length can be called an ad- vantage. Then tire changes by both the Stutz drivers gave the center of the stage to the two Latins and they went to the fore, Resta leading at the end of 100 miles, but de Palma was so close that smoke of the Peugeot’s exhaust partially veiled the hood of the Mercedes. At the completion of 150 miles, Resta and de Palma were a lap ahead of Wilcox, running in third place, and paying little attention to the other contenders. A tire change by de Palma gave Resta an opportunity to increase his lead by 1 minute on the sixty-third lap but after 10 more miles of heart-breaking pace-setting, the Peugeot driver was forced to stop for gasoline and a rear wheel and the Mercedes shot to the front.

Forty seconds separated de Palma and Resta when they pounded over the wire at the completion of 200 miles, the Mercedes leading the Peugeot at that time. Resta cut down this lead to 25 seconds in the next ten circuits of the oval and with half the race over, Ralph had but 20 seconds to spare.

Fifty Miles Neck and Neck

De Palma could not gain an inch in the next 50 miles but retained the lead, making up the ground lost on the straight-aways by a burst of speed at the turns. With 300 miles covered, de Palma decided to waste 2 precious minutes and surrender the lead in order to fit his car for the last eighty laps of the grueling grind.

On the one hundred and twenty-eighth and the one hundred and twenty-ninth laps, Mercedes and Peugeot came down the home stretch hood-to-hood although the French car had a lead of a lap over its mechanical rival from the realm of the kaiser. On one turn, Resta skidded and de Palma barely missed hitting him. This seemed to take the heart out of the speed king of the Panama-Pacific exposition and he did not go into the curves at such high speed thereafter.

Resta’s stop for a rear tire on the one hundred and thirty-seventh lap gave de Palma a chance to thunder to the front once more. The Peugeot driver seemed very nervous, for he lost control of his car temporarily and skidded into the concrete wall before bringing his mount to a halt.

With de Palma leading by 1 minute, 9 seconds, the duel was resumed but the Mer- cedes driver had a decided advantage, sticking to the outside of the track and forcing Resta to slow down before taking the turns.

De Palma was not only out to show the throng that he was the master of the invader who captured the Vanderbilt cup and grand prize at San Francisco but he was determined to have his revenge on fate and conquer the jinx that snatched victory out of his grimy hand on the one hundred and ninety-seventh lap of the 1912 500-mile race when the engine of his car played him false. He gradually drew away from his weakening rival until at the completion of 400 miles, he had an advantage of one lap.

Mercedes Sounds Hymn of Hate

Resta was beaten then. De Palma had driven the heart out of him. The Peugeot seemed to have lost its heart, too. It was sluggish. It was without the burst of speed necessary to overtake the Mercedes and pass the cream-colored car. Its roar was less menacing. The engine of the Mercedes was sounding a hymn of hate, a song of revenge that would have made the kaiser’s waxed moustache bristle with joy could he have heard it. The German car shot by the stands like a great projectile.

1912 Vision Before de Palma

De Palma knows that the race is never won until the checkered flag has dropped. He learned that 3 years ago. The lesson cost him $20,000 or more. As he thundered over the bricks today, he thought of the tragedy of 1912, the tragedy in which he played the principal part but played it like the game sportsman that he is. He completed the one hundred and ninety-fifth lap, the one hundred and ninety-sixth. Then he asked himself a question, a question that he was afraid to answer: „Will history repeat? Will the one hundred and ninety-seventh lap find me tugging frantically on the bonnet straps and tearing at the hot steel of an unfaithful motor?“

The great Italian drove that lap, the fatal lap of 1912, with his heart in his mouth, with the sweat of anxiety pouring down over his face. He completed it. After crossing the wire to start on the last two circuits of the oval, he smiled at the thought of his conquest of fate. Then he heard the voice of his jinx, the jinx that has no mercy. The engine started to miss. De Palma increased his speed. Another lap was turned. The green flag waved over his head, but the motor was hitting only on three. Would it stand up under the strain of the last 2½ miles or would it fail him as the engine of the old Mercedes had failed him 3 years before?

Persistence such as de Palma has is not to be denied. He completed his two hundredth lap. The car did not play him false. It stood up under the drive that he gave it, one cylinder protesting but three refusing to play traitor to the man who placed his reliance upon them. The Italian’s heart throbs and the throbs of the motor were in harmony. Man and machine had not toiled and dared in vain. De Palma had achieved the greatest ambition of his life. He had evened the score with fate. He had overcome his jinx. He had won the 500-mile race.

Italian Modest in Victory

De Palma took victory today as modestly as he accepted defeat 3 years ago gamely. After the race was won, he did not stop at his pits but drove to his garage and closed the doors behind himself and his triumphant mount. The most popular victor in the history of the international sweepstakes, he tried to avoid the homage that 60,000 hero worshippers paid him. That he was happy, supremely happy, could be told by the smile on his lips and the gleam in his eyes.

While the crowd was congratulating him, he thought only of his grease-splattered helper, Louis Fountaine, and paid him the following tribute:

„Louis, you’re an awful little runt, but believe me, you’re some mechanic!“

In winning today’s race, de Palma upset all precedent. This is the first Hoosier classic in which an individual entry has been returned victor. De Palma also broke the 2 to 2 tie score in which America and France were deadlocked before the starting bomb sounded at ten o’clock this morning. Europe has won the rubber race; that is, a foreign car has been crowned with the laurels of international champion.

The story of today’s race might have been different had another motor stood up under the heartless punishment as faithfully as did that which roared under the hood of the Mercedes. If it had, Howdy Wilcox might be the toast of Indianapolis tonight. Howdy’s Stutz, which made the fastest qualifying lap in the elimination trials, rebelled before it was hardly warmed up to its work. It started missing at the end of 100 miles and Wil- cox finished the last century with only two cylinders hitting.

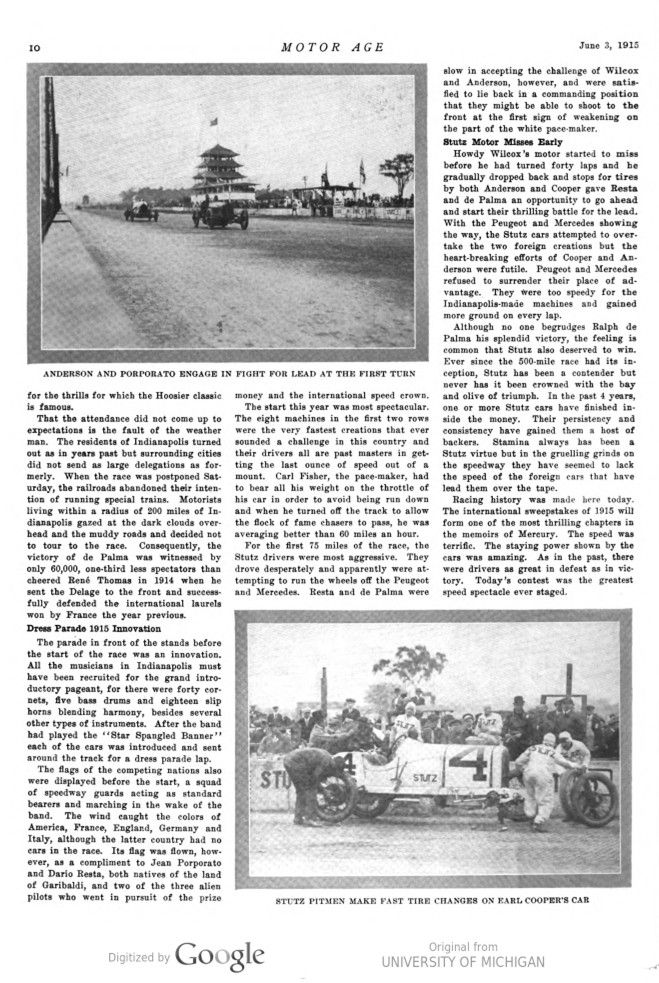

Stutz Tire Changes Costly

Stutz was not favored with the tire luck that was such a paramount factor in the achievements of the Mercedes and Peugeot. Whereas de Palma and Resta stopped for tires only two times, Cooper and Anderson wasted precious seconds in five stops apiece and Wilcox came into the pits three times. The Stutz pitmen lost little time in changing wheels and worked with the speed of magicians.

The postponement of the race from Saturday to today because of inclement weather resulted in the falling off of attendance, the crowd not being as large as in 1913 and 1914. It is estimated that about 60,000 spectators witnessed de Palma’s victory. Because of the marshy condition of the infield, only a few cars were permitted to park inside the track, holders of parking places being given grand stand seats free by the management. Thousands of cars were left outside of the enclosure, 2,500 getting an airing before the plant of the Prest-O-Lite company alone.

Spectators Wade in Mud

The roads and walks inside the colossal enclosure were ankle-deep in mud and the Beau Brummels who wore white silk hose wished that they hadn’t. After the completion of the race, when the mud-spattered crowd finally got back to town, the bootblacks did a rushing business.

The speedway management had a herd of teams on hand to render aid to motorists whose cars might get mired in the mud. There was little need of them, however, as the roads and infield dried up in the afternoon and the few hundred machines that were permitted to park around the track were able to get out under their own power.

The threatening weather of the early morning failed to put a damper on the enthusiasm of the speed fans, and they stormed the gates as early as 5 o’clock. When the tiny Cornelian, the first car on the course, left its garage and went to its pit, there were several thousand spectators on the job, expectant and eager for the thrills for which the Hoosier classic is famous.

That the attendance did not come up to expectations is the fault of the weather man. The residents of Indianapolis turned out as in years past but surrounding cities did not send as large delegations as formerly. When the race was postponed Saturday, the railroads abandoned their intention of running special trains. Motorists living within a radius of 200 miles of Indianapolis gazed at the dark clouds overhead and the muddy roads and decided not to tour to the race. Consequently, the victory of de Palma was witnessed by only 60,000, one-third less spectators than cheered René Thomas in 1914 when he sent the Delage to the front and successfully defended the international laurels won by France the year previous.

Dress Parade 1915 Innovation

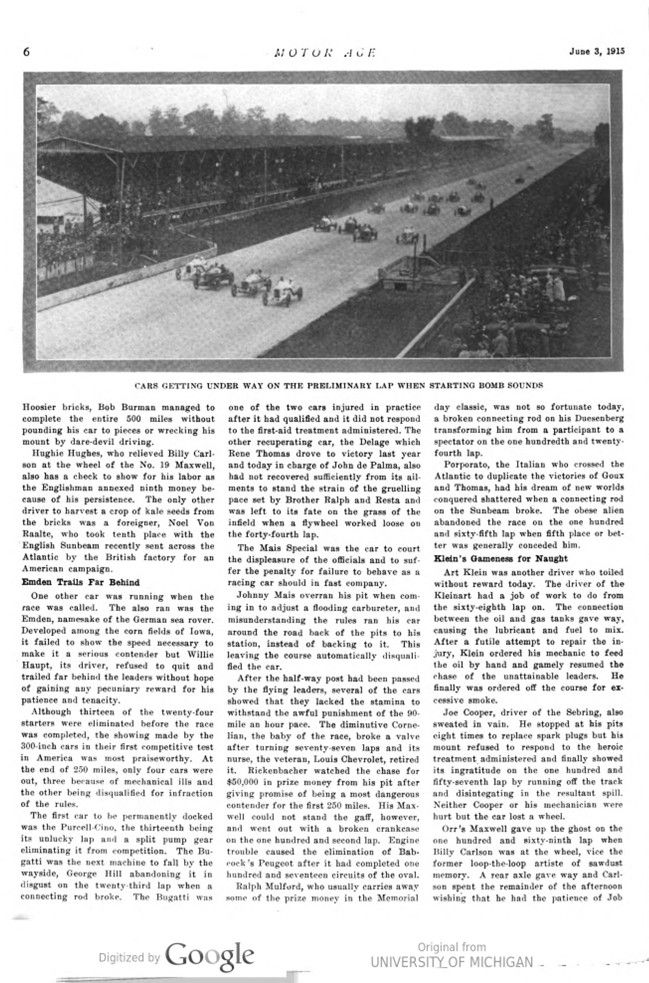

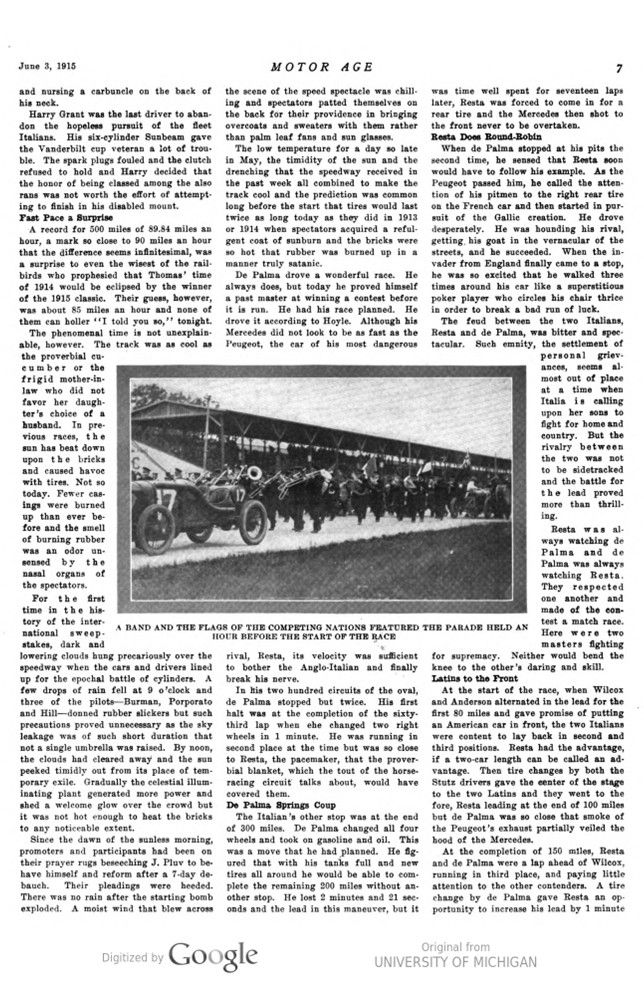

The parade in front of the stands before the start of the race was an innovation. All the musicians in Indianapolis must have been recruited for the grand introductory pageant, for there were forty cornets, five bass drums and eighteen slip horns blending harmony, besides several other types of instruments. After the band had played the „Star Spangled Banner“ each of the cars was introduced and sent around the track for a dress parade lap.

The flags of the competing nations also were displayed before the start, a squad of speedway guards acting as standard bearers and marching in the wake of the band. The wind caught the colors of America, France, England, Germany and Italy, although the latter country had no cars in the race. Its flag was flown, however, as a compliment to Jean Porporato and Dario Resta, both natives of the land of Garibaldi, and two of the three alien pilots who went in pursuit of the prize money and the international speed crown.

The start this year was most spectacular. The eight machines in the first two rows were the very fastest creations that ever sounded a challenge in this country and their drivers all are past masters in getting the last ounce of speed out of a mount. Carl Fisher, the pace-maker, had to bear all his weight on the throttle of his car in order to avoid being run down and when he turned off the track to allow the flock of fame chasers to pass, he was averaging better than 60 miles an hour.

For the first 75 miles of the race, the Stutz drivers were most aggressive. They drove desperately and apparently were attempting to run the wheels off the Peugeot and Mercedes. Resta and de Palma were slow in accepting the challenge of Wilcox and Anderson, however, and were satisfied to lie back in a commanding position that they might be able to shoot to the front at the first sign of weakening on the part of the white pace-maker.

Stutz Motor Misses Early

Howdy Wilcox’s motor started to miss before he had turned forty laps and he gradually dropped back and stops for tires by both Anderson and Cooper gave Resta and de Palma an opportunity to go ahead and start their thrilling battle for the lead. With the Peugeot and Mercedes showing the way, the Stutz cars attempted to overtake the two foreign creations but the heart-breaking efforts of Cooper and Anderson were futile. Peugeot and Mercedes refused to surrender their place of advantage. They were too speedy for the Indianapolis-made machines and gained more ground on every lap.

Although no one begrudges Ralph de Palma his splendid victory, the feeling is common that Stutz also deserved to win. Ever since the 500-mile race had its inception, Stutz has been a contender but never has it been crowned with the bay and olive of triumph. In the past 4 years, one or more Stutz cars have finished inside the money. Their persistency and consistency have gained them a host of backers. Stamina always has been a Stutz virtue but in the grueling grinds on the speedway they have seemed to lack the speed of the foreign cars that have lead them over the tape.

Racing history was made here today. The international sweepstakes of 1915 will form one of the most thrilling chapters in the memoirs of Mercury. The speed was terrific. The staying power shown by the cars was amazing. As in the past, there were drivers as great in defeat as in victory. Today’s contest was the greatest speed spectacle ever staged.

Photo captions. – June 3, 1915 – MOTOR AGE

CARS GETTING UNDER WAY ON THE PRELIMINARY LAP WHEN STARTING BOMB SOUNDS.

A BAND AND THE FLAGS OF THE COMPETING NATIONS FEATURED THE PARADE HELD AN HOUR BEFORE THE START OF THE RACE.

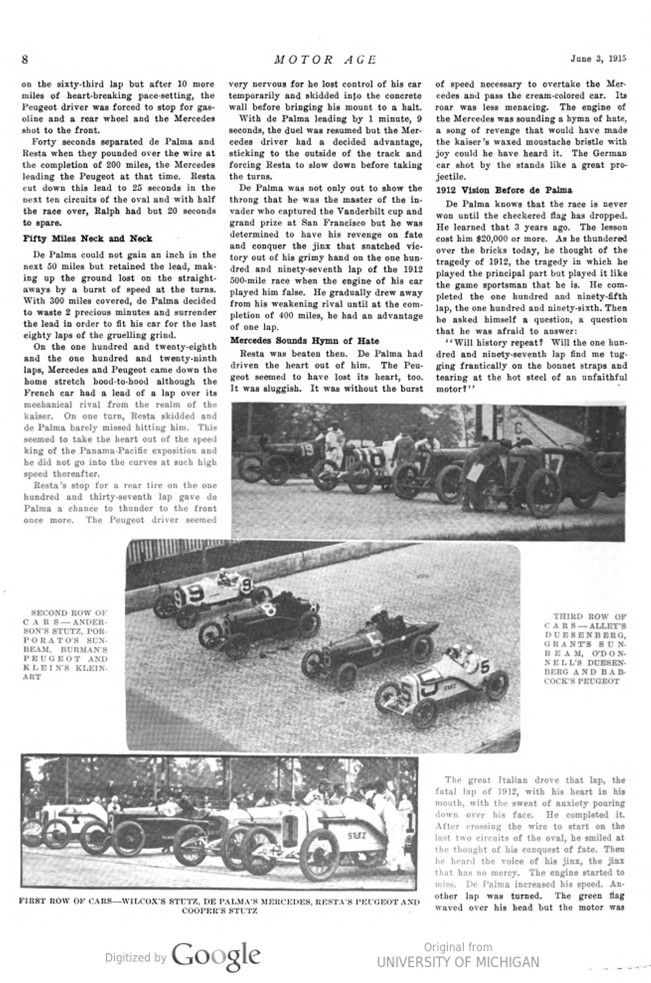

FIRST ROW OF CARS – WILCOX’S STUTZ, DE PALMA’S MERCEDES, RESTA’S PEUGEOT AND COOPER’S STUTZ.

SECOND ROW OF CARS – ANDERSON’S STUTZ, PORPORATO’S SUNBEAM, BURMAN’S PEUGEOT AND KLEIN’S KLEINART.

THIRD ROW OF CARS – ALLEY’S DUESENBERG, GRANT’S SUNBEAM, O’DONNELL’S DUESENBERG AND BABCOCK’S PEUGEOT.

FOURTH ROW OF CARS – DE PALMA’S DELAGE, VON RAALTE’S SUNBEAM, COOPER’S S EBRING AND CARLSON’S MAXWELL.

FIFTH ROW OF CARS – ORR’S MAXWELL, MULFORD’S DUESENBERG, RICKENBACHER’S MAXWELL AND MAIS‘ MAIS SPECIAL.

SIXTH ROW OF CARS – COX’S PURCELL SPECIAL, HILL’S BUGATTI, CHEVROLET’S CORNELIAN AND HAUPT’S EMDEN.

ANDERSON AND PORPORATO ENGAGE IN FIGHT FOR LEAD AT THE FIRST TURN.

STUTZ PITMEN MAKE FAST TIRE CHANGES ON EARL COOPER’S CAR.