Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

AUTOMOBILE TOPICS – June 5, 1915 – pages 289 – 312

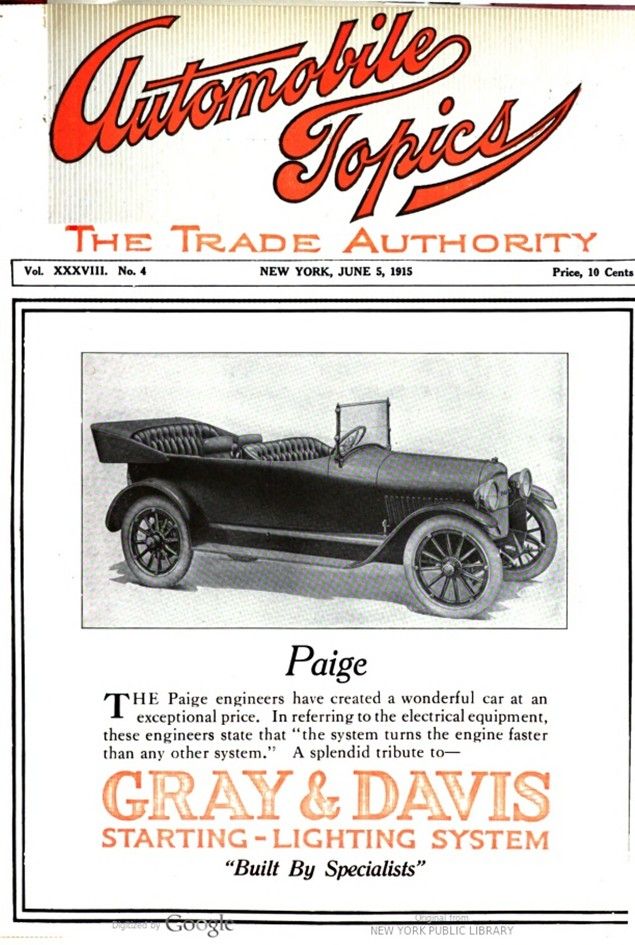

DE PALMA BREAKS 500-MILE RACE RECORD

Wins Famous Contest at Indianapolis with an Average of 89.84 Miles an Hour

Eclipses Previous Mark, Set Last Year by Thomas, by Seven Miles an Hour

Resta Is Second in Peugeot

Entire Stutz Team of Three Finishes Intact and with Two Cars Above Last Year’s Figure

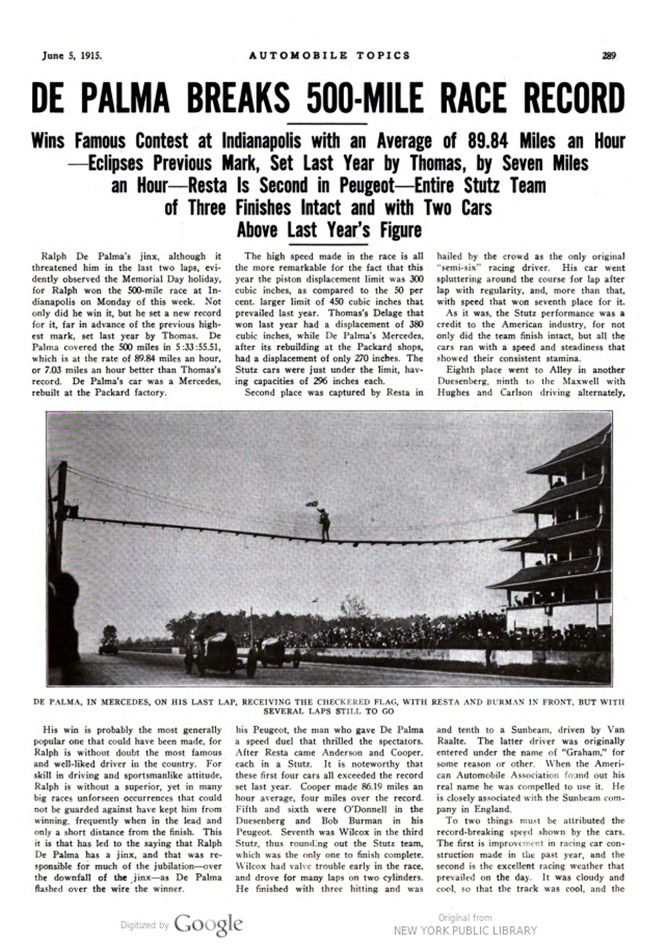

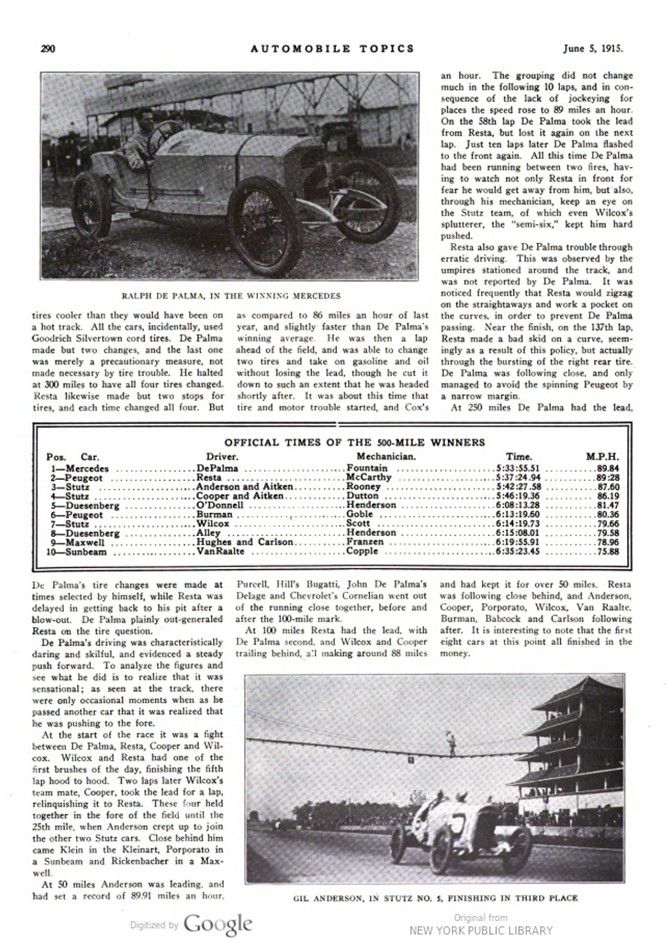

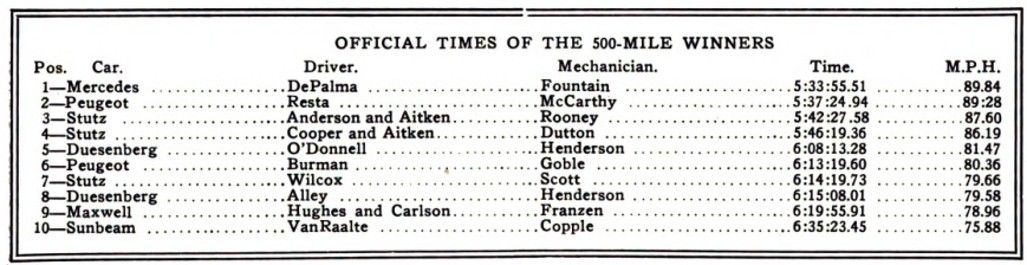

Ralph De Palma’s jinx, although it threatened him in the last two laps, evidently observed the Memorial Day holiday, for Ralph won the 500-mile race at Indianapolis on Monday of this week. Not only did he win it, but he set a new record for it, far in advance of the previous highest mark, set last year by Thomas. De Palma covered the 500 miles in 5:33:55.51, which is at the rate of 89.84 miles an hour, or 7.03 miles an hour better than Thomas’s record. De Palma’s car was a Mercedes, rebuilt at the Packard factory.

His win is probably the most generally popular one that could have been made, for Ralph is without doubt the most famous and well-liked driver in the country. For skill in driving and sportsmanlike attitude, Ralph is without a superior, yet in many big races unforeseen occurrences that could not be guarded against have kept him from winning, frequently when in the lead and only a short distance from the finish. This it is that has led to the saying that Ralph De Palma has a jinx, and that was responsible for much of the jubilation – over the downfall of the jinx – as De Palma flashed over the wire the winner.

The high speed made in the race is all the more remarkable for the fact that this year the piston displacement limit was 300 cubic inches, as compared to the 50 per cent. larger limit of 450 cubic inches that prevailed last year. Thomas’s Delage that won last year, had a displacement of 380 cubic inches, while De Palma’s Mercedes, after its rebuilding at the Packard shops, had a displacement of only 270 inches. The Stutz cars were just under the limit, having capacities of 296 inches each.

Second place was captured by Resta in his Peugeot, the man who gave De Palma a speed duel that thrilled the spectators. After Resta came Anderson and Cooper, each in a Stutz. It is noteworthy that these first four cars all exceeded the record set last year. Cooper made 86.19 miles an hour average, four miles over the record. Fifth and sixth were O’Donnell in the Duesenberg and Bob Burman in his Peugeot. Seventh was Wilcox in the third Stutz, thus rounding out the Stutz team, which was the only one to finish complete. Wilcox had valve trouble early in the race and drove for many laps on two cylinders. He finished with three hitting and was hailed by the crowd as the only original „semi-six“ racing driver. His car went spluttering around the course for lap after lap with regularity, and, more than that, with speed that won seventh place for it.

As it was, the Stutz performance was a credit to the American industry, for not only did the team finish intact, but all the cars ran with a speed and steadiness that showed their consistent stamina.

Eighth place went to Alley in another Duesenberg, ninth to the Maxwell with Hughes and Carlson driving alternately, and tenth to a Sunbeam, driven by Van Raalte. The latter driver was originally entered under the name of „Graham,“ for some reason or other. When the American Automobile Association found out his real name he was compelled to use it. He is closely associated with the Sunbeam company in England.

To two things must be attributed the record-breaking speed shown by the cars. The first is improvement in racing car construction made in the past year, and the second is the excellent racing weather that prevailed on the day. It was cloudy and cool, so that the track was cool, and the tires cooler than they would have been on a hot track. All the cars, incidentally, used Goodrich Silvertown cord tires. De Palma made but two changes, and the last one was merely a precautionary measure, not made necessary by tire trouble. He halted at 300 miles to have all four tires changed. Resta likewise made but two stops for tires, and each time changed all four. But De Palma’s tire changes were made at times selected by himself, while Resta was delayed in getting back to his pit after a blow-out. De Palma plainly out-generaled Resta on the tire question.

De Palma’s driving was characteristically daring and skillful and evidenced a steady push forward. To analyze the figures and see what he did is to realize that it was sensational; as seen at the track, there were only occasional moments when as he passed another car that it was realized that he was pushing to the fore.

At the start of the race, it was a fight between De Palma, Resta, Cooper and Wilcox. Wilcox and Resta had one of the first brushes of the day, finishing the fifth lap hood to hood. Two laps later Wilcox’s teammate, Cooper, took the lead for a lap, relinquishing it to Resta. These four held together in the fore of the field until the 25th mile, when Anderson crept up to join the other two Stutz cars. Close behind him came Klein in the Kleinart, Porporato in a Sunbeam and Rickenbacher in a Maxwell.

At 50 miles Anderson was leading and had set a record of 89.91 miles an hour, as compared to 86 miles an hour of last year, and slightly faster than De Palma’s winning average. He was then a lap ahead of the field and was able to change two tires and take on gasoline and oil without losing the lead, though he cut it down to such an extent that he was headed shortly after. It was about this time that tire and motor trouble started, and Cox’s Purcell, Hill’s Bugatti, John De Palma’s Delage and Chevrolet’s Cornelian went out of the running close together, before and after the 100-mile mark.

At 100 miles Resta had the lead, with De Palma second, and Wilcox and Cooper trailing behind, all making around 88 miles an hour. The grouping did not change much in the following 10 laps, and in consequence of the lack of jockeying for places the speed rose to 89 miles an hour. On the 58th lap De Palma took the lead from Resta but lost it again on the next lap. Just ten laps later De Palma flashed to the front again. All this time De Palma had been running between two fires, having to watch not only Resta in front for fear he would get away from him, but also, through his mechanician, keep an eye on the Stutz team, of which even Wilcox’s splutterer, the „semi-six,“ kept him hard pushed.

Resta also gave De Palma trouble through erratic driving. This was observed by the umpires stationed around the track and was not reported by De Palma. It was noticed frequently that Resta would zigzag on the straightaways and work a pocket on the curves, in order to prevent De Palma passing. Near the finish, on the 137th lap, Resta made a bad skid on a curve, seemingly as a result of this policy, but actually through the bursting of the right rear tire. De Palma was following close, and only managed to avoid the spinning Peugeot by a narrow margin.

At 250 miles De Palma had the lead and had kept it for over 50 miles. Resta was following close behind, and Anderson, Cooper, Porporato, Wilcox, Van Raalte, Burman, Babcock and Carlson following after. It is interesting to note that the first eight cars at this point all finished in the money.

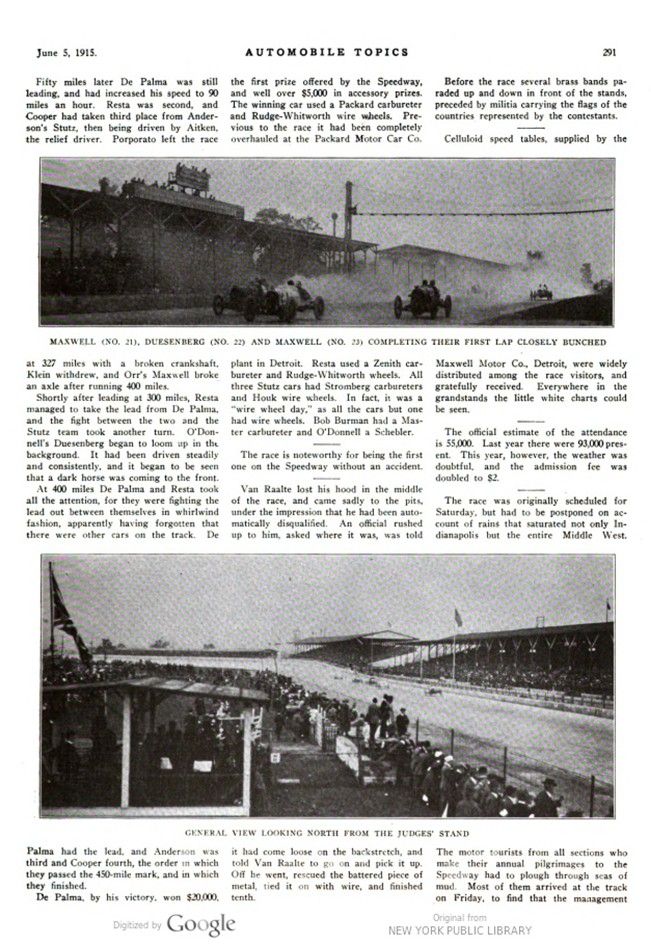

Fifty miles later De Palma was still leading and had increased his speed to 90 miles an hour. Resta was second, and Cooper had taken third place from Anderson’s Stutz, then being driven by Aitken, the relief driver. Porporato left the race at 327 miles with a broken crankshaft, Klein withdrew, and Orr’s Maxwell broke an axle after running 400 miles.

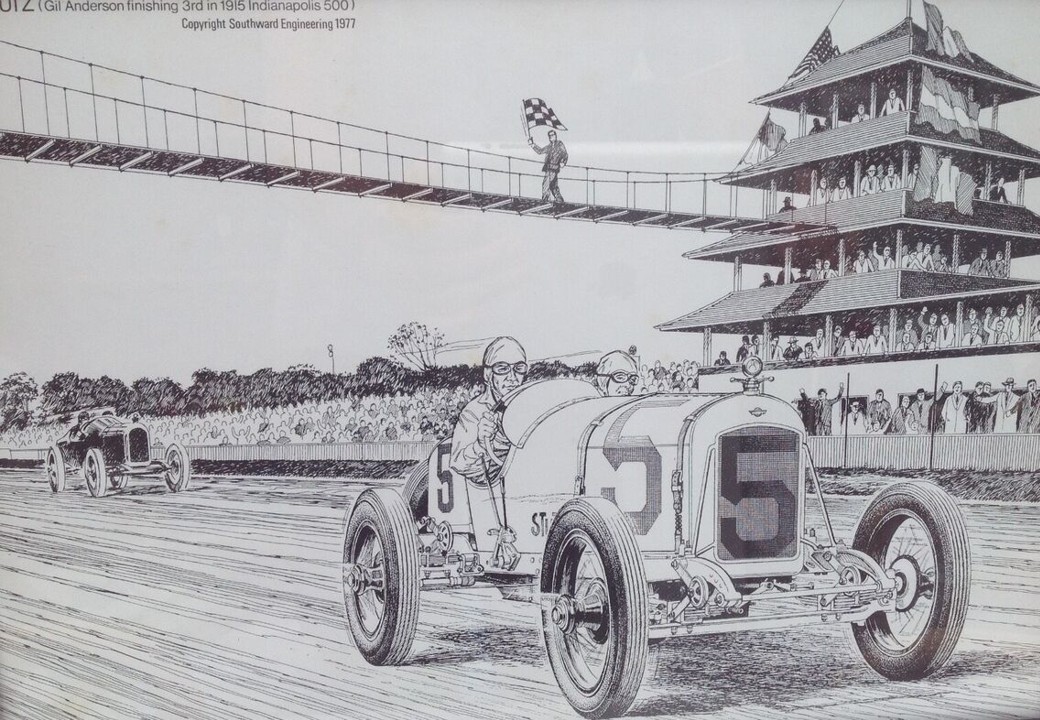

Gil Anderson, in Stutz No. 5, finishing in Third Place – picture source: Automobile Topics.

Indianapolis 500 1915 – Stutz – Gil Anderson – passing the finish line – drawing by Alan Mitchell – picture source: ebay

Shortly after leading at 300 miles, Resta managed to take the lead from De Palma, and the fight between the two and the Stutz team took another turn. O’Donnell’s Duesenberg began to loom up in the background. It had been driven steadily and consistently, and it began to be seen that a dark horse was coming to the front.

At 400 miles De Palma and Resta took all the attention, for they were fighting the lead out between themselves in whirlwind fashion, apparently having forgotten that there were other cars on the track. De Palma had the lead, and Anderson was third and Cooper fourth, the order in which they passed the 450-mile mark, and in which they finished.

De Palma, by his victory, won $20,000, the first prize offered by the Speedway, and well over $5,000 in accessory prizes. The winning car used a Packard carbureter and Rudge-Whitworth wire wheels. Previous to the race it had been completely overhauled at the Packard Motor Car Co. plant in Detroit. Resta used a Zenith carbureter and Rudge-Whitworth wheels. All three Stutz cars had Stromberg carbureters and Houk wire wheels. In fact, it was a „wire wheel day,“ as all the cars but one had wire wheels. Bob Burman had a Master carbureter and O’Donnell a Schebler.

—–

The race is noteworthy for being the first one on the Speedway without an accident.

—-

Van Raalte lost his hood in the middle of the race, and came sadly to the pits, under the impression that he had been automatically disqualified. An official rushed up to him, asked where it was, was told it had come loose on the backstretch and told Van Raalte to go on and pick it up. Off he went, rescued the battered piece of metal, tied it on with wire, and finished tenth.

Before the race several brass bands paraded up and down in front of the stands, preceded by militia carrying the flags of the countries represented by the contestants.

———-

Celluloid speed tables, supplied by the Maxwell Motor Co., Detroit, were widely distributed among the race visitors, and gratefully received. Everywhere in the grandstands the little white charts could be seen.

—-

The official estimate of the attendance is 55,000. Last year there were 93,000 present. This year, however, the weather was doubtful, and the admission fee was doubled to $2.

—-

The race was originally scheduled for Saturday but had to be postponed on account of rains that saturated not only Indianapolis but the entire Middle West. The motor tourists from all sections who make their annual pilgrimages to the Speedway had to plough through seas of mud. Most of them arrived at the track on Friday, to find that the management had just cast an eye on the weather conditions and decided to postpone the event to Monday.

Of course there was disappointment; there was grumbling, too, aplenty. Many roasted the management for its lack of cleverness in announcing so early what was spitefully declared to be but a prearranged plan to keep the thousands of strangers in the city for two extra days. Later on, when the rain continued to fall up to Saturday night, the criticism had its point turned aside, and more thoughtful consideration of the situation brought forth commendation. While some of the visitors left in a huff Friday, the great majority stayed over, even though as time went on there seemed to be no better prospect for holding the race on Monday.

Wiser counsel also pointed out that the Speedway management had really taken excellent advantage of the opportunity offered by the alternative of two days on which the race could be run this year. In the very nature of things, it could not be expected that the fair weather that has marked all previous 500-mile races would continue to grace the event. Therefore, it was decided to choose the first of the two days, even though it was not a holiday universally and though on that account the attendance might be expected to be less than usual. If the weather were clear that day, all well and good; if it were not clear, there was the second day still open, with a day of grace for the track to dry off.

Either way, the Speedway stood to lose something; on Saturday, from the fact that the attendance would suffer because it was not a holiday; on Monday, from the losses natural to postponed events. The Speedway management thought it better to imperil the receipts somewhat by the Saturday date rather than imperil the running of the race more by choosing Monday.

When this was seen by the Indianapolis visitors, they had no more complaints to make, with the exception that perhaps it might have been possible to have announced the postponement on Thursday night and thereby headed off a large number of visitors who did not start for the track until Friday.

Aside from this, every effort was made to get the track in condition, with entire success as far as the track surface proper was concerned. The infield, however, and the tunnels leading to the parking spaces were seas of mud and water, and hopeless of improvement by any medium save the rays of the sun. Consequently, the number of parked cars was materially cut down, and those that did brave the terrors of the infield mud had a hard time of it indeed. Some of the cars had to be hauled out of the tunnels, all muddy and slimy, with block and tackle.

—-

The cool weather affected the appearance of the grandstands, which were decidedly sober in tone compared with previous races. Dark caps and raincoats took the place of straw hats and shirt sleeves. Venders of lemonade and similar cooling drinks had gallons left unsold, and about the most popular man was he who conducted a booth where fried chicken was to be had. „Hot dogs“ also had their day.

One of the rumors that circulated about Indianapolis Monday night was to the effect that De Palma had finished the last three laps with a broken connecting rod, which had punched two holes in the crankcase. His car was clattering dreadfully in the last two laps, and the crankcase had spilled out all its oil.

—-

Among the unusual troubles was that of the Kleinart. This carried its oil and gasoline in the one tank, separated by a partion. Violent sloshing of the liquid about during the race broke the partition loose, so that the two mixed, with too much oil in the mixture. The car slowed up considerably, and finally was ruled off the course for smoking.

—-

Pit work was exceedingly speedy this year, tire changes in 30 seconds being the rule. This was ascribed to studied practice during the preliminary practice for the race, under the watchful eyes of team managers and wire wheel experts.

—-

Indianapolis Doctor Sues Duesenberg for Old Race Bill

Following the announcement that two Duesenberg cars had won places in the Indianapolis race, and $4,600 in prize money, Dr. Horace R. Allen filed suit in the Superior Court in Indianapolis against F. S. Duesenberg, of Sioux City, Ia., for $316 for professional services rendered. Dr. Allen stated that he attended Jack Towers and Lee Gunning when they were injured in the 500-mile race of 1913, in which they drove a Duesenberg. He says his bill was not paid, and he now sues Duesenberg, who owned the car. The Indianapolis Motor Speedway is made a co-defendant with Duesenberg because it holds the prize money won by the two cars in this year’s race.

—-

Stutz Stars in Newark Races

Joe Dickinson in a Stutz was the star of the Memorial Day racing, May 31, in Newark, N. J. He won four of the five races in which he started, and in his fifth race was eliminated by a wheel bearing running dry.

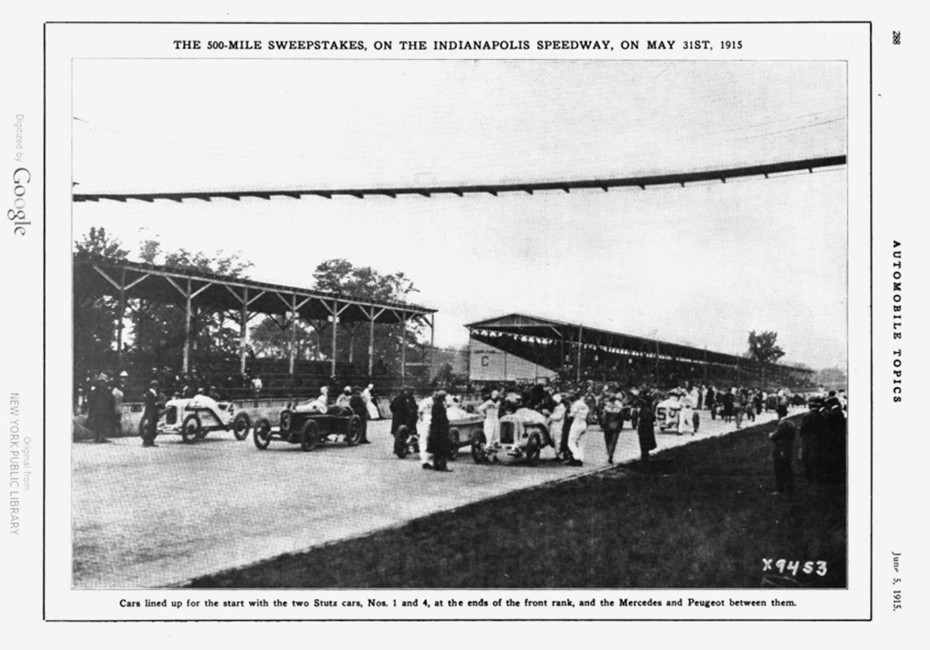

Photo Caption Page 288.

The 500-Mile Sweepstakes, on the Indianapolis Speedway, on May 31st, 1915. Cars lined up for the start with the two Sturz cars, No. 1 and 4, at the end of the front rank, and the Mercedes and Peugeot between them. Automobile Topics.

Substitute for photo on page 290.

Driver Ralph DePalma and Mechanic Louis Fontaine in the Mercedes Special. Picture source: Indianapolis Motor Speedway, IMS

Photo Captions – June 5, 1915 – AUTOMOBILE TOPICS

Page 289

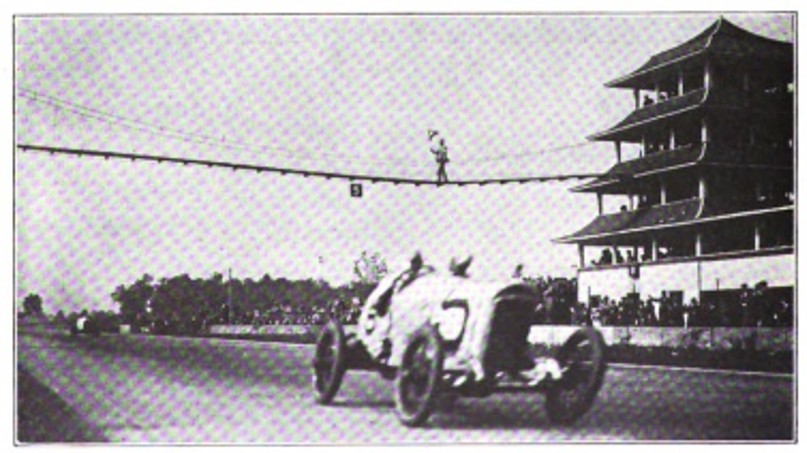

DE PALMA, IN MERCEDES, ON HIS LAST LAP, RECEIVING THE CHECKERED FLAG, WITH RESTA AND BURMAN IN FRONT, BUT WITH SEVERAL LAPS STILL TO GO

Page 290

RALPH DE PALMA, IN THE WINNING MERCEDES – GIL ANDERSON, IN STUTZ NO. 5, FINISHING IN THIRD PLACE

Page 291

MAXWELL (NO. 21), DUESENBERG (NO. 22) AND MAXWELL (NO. 23) COMPLETING THEIR FIRST LAP CLOSELY BUNCHED

GENERAL VIEW LOOKING NORTH FROM THE JUDGES‘ STAND

Page 292

GENERAL VIEW LOOKING NORTH ALONG THE PITS, MAXWELL CARS IN FOREGROUND – ON THE CURVE TURNING INTO THE LONG STRETCH