Over many years, the technical specialist and highly rated author Peter Martin Heldt wrote for several American automotive magazines. In this 1927 article in Automotive Industries, he explains the different aspects of the then upcoming front-wheel drive. Because of its lengthy write, it’s divided here in two parts. Not only an interesting read, but I find it baffling how in-depth he decsribes the many different aspects of front-wheel drive.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Automotive Industries, Vol. 56, No. 27, June 4, 1927

Impasse in Car Development May be Circumvented by FRONT WHEEL DRIVE – Part I

Will permit still further lowering of bodies and this is one reason why it may appeal to designers.

By P. M. HELDT (Engineering Editor, Automotive Industries)

FRONT wheel drive for automobiles is an old idea; many patents have been taken out on various embodiments thereof, and numerous experimental models have been built, but up to the present time the drive has found no application on stock cars in this country. If, in spite of this seeming failure, it is made the subject of an investigation in this article, it is because a sort of impasse has been reached in the development of passenger cars from which the front wheel drive may prove „the way out.“ Cars have been built lower year after year, but with the conventional bevel gear drive, at least, the propeller shaft now puts a limit to further progress in this direction; front wheel drive would remove this limitation.

The chief advantage claimed by the early protagonists of the front wheel drive was that its traction conditions are better than those of the rear drive. This holds particularly in the case of soft roads, into which the wheels sink to a considerable depth. If the front wheels are in a mud puddle, for instance, the resultant of the weight on them and of the forward push of rear driving wheels tends to force them deeper and deeper into the mud. With front wheel drive, on the other hand, the propelling force, which acts tangentially at the rims of the driving wheels, tends to lift them out of the hole.

That there is a certain advantage in the way of power required and of ability to negotiate heavy roads seems a logical conclusion – the writer does not remember having seen any test data on the point – but this was never of sufficient importance to balance the disadvantage of the greater mechanical complication of a combined driving and steering axle. It is of less importance today than ever before, because our highways are being improved at a rapid rate, and it certainly does not make any appreciable difference with respect to power consumption on concrete or asphalt roads whether the car is being driven by the front or rear wheels.

Undoubtedly the chief reason which might make the front wheel drive attractive at the present time is that it eliminates practically all restrictions with respect to lowering of the body. In a car equipped with this type of drive the rear axle would be a dead or non-rotating axle which could extend through the rear seat box, and if this did not suffice, it might even be „cranked,“ as it has been on certain special-purpose front drive trucks with loading platform close to the ground.

A further advantage would be that it would improve riding qualities. Riding comfort is roughly a function of the ratio of sprung to unsprung weight, and if the rear axle were rid of its differential gear and other driving members it could be made much lighter than at present. With front wheel drive the differential gear and its housing would be supported on the springs, forming a part of the powerplant, and while the rear axle would be relieved of unsprung weight, that of the front axle would not be correspondingly increased.

A further point in favor of front wheel drive is that it permits of braking by means of the front wheels without carrying brake drums on these wheels and without the often somewhat complicated mechanism for operating front brakes. A single brake drum on the propeller shaft, either between the transmission and the drive gear or else in front of the latter, would serve to impose equal braking effects on the two front wheels. This transmission brake, acting on the front wheels, could be hooked up with the linkage of brakes acting on drums on the rear wheels to give four-wheel braking. An additional set of brakes could be fitted to the rear wheels for emergency service, if considered desirable, and the arrangement certainly permits of a considerable simplification.

The elimination of a long propeller shaft between the transmission and the rear axle also could be counted as an advantage. This shaft, if not accurately balanced, tends to whirl at certain high speeds, these critical speeds being marked by roughness in the running of the car. In the front-driven car the single long propeller shaft is replaced by two shorter transverse shafts which in most designs run at much lower speed, so that there is no occasion for whirling.

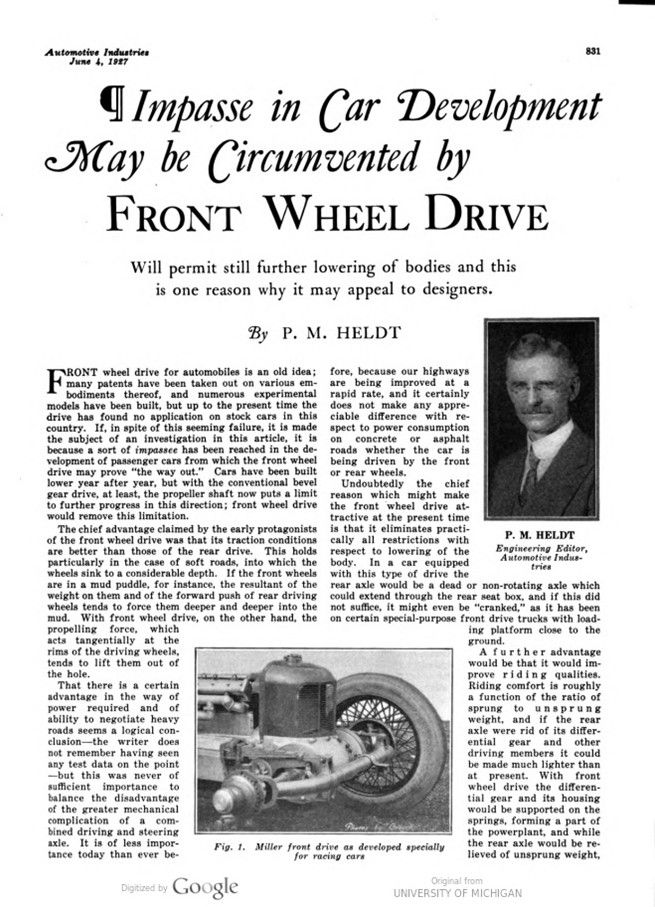

Front drive already has gained a certain measure of popularity in connection with racing cars, and whatever success it might achieve on tracks, would help to smooth its way into the commercial field. In racing on circular tracks much additional resistance is encountered as a car swings into a curve, owing to the fact that the driving force, which acts in the direction of the car axis, makes large angles with the planes of rotation of the front wheels. A certain amount of sideward slip of these wheels is caused. Moreover, the unequal resistances encountered by the two front wheels, due to the fact that they are deflected through different angles, tends to cause rear wheel skidding.

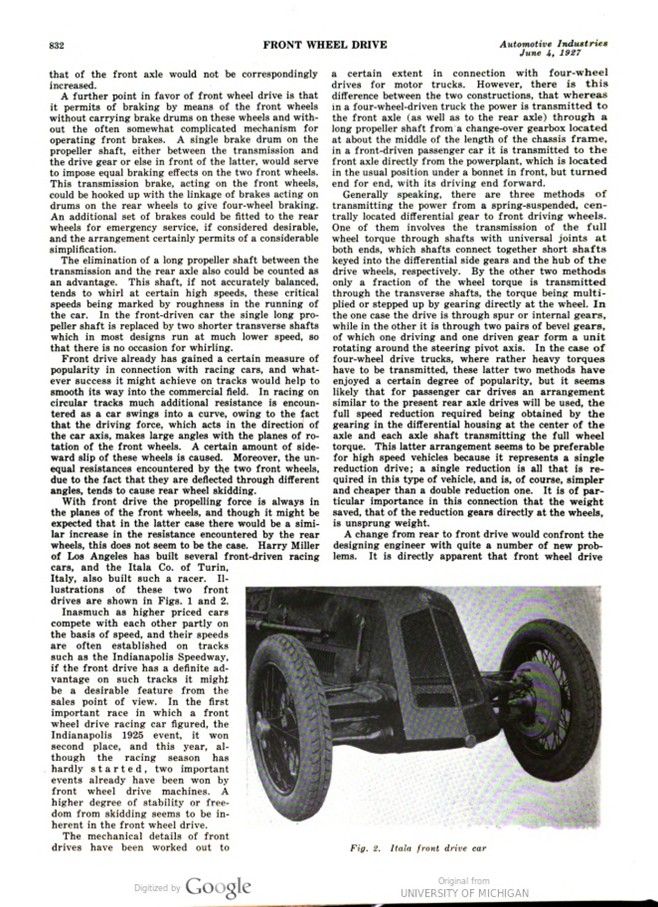

With front drive the propelling force is always in the planes of the front wheels, and though it might be expected that in the latter case there would be a similar increase in the resistance encountered by the rear wheels, this does not seem to be the case. Harry Miller of Los Angeles has built several front-driven racing cars, and the Itala Co. of Turin, Italy, also built such a racer. Illustrations of these two front drives are shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Inasmuch as higher priced cars compete with each other partly on the basis of speed, and their speeds are often established on tracks such as the Indianapolis Speedway, if the front drive has a definite advantage on such tracks, it might be a desirable feature from the sales point of view. In the first important race in which a front wheel drive racing car figured, the Indianapolis 1925 event won second place, and this year, although the racing season has hardly started, two important events already have been won by front wheel drive machines. A higher degree of stability or freedom from skidding seems to be inherent in the front wheel drive.

The mechanical details of front drives have been worked out to a certain extent in connection with four-wheel drives for motor trucks. However, there is this difference between the two constructions, that whereas in a four-wheel-driven truck the power is transmitted to the front axle (as well as to the rear axle) through a long propeller shaft from a change-over gearbox located at about the middle of the length of the chassis frame, in a front-driven passenger car it is transmitted to the front axle directly from the powerplant, which is located in the usual position under a bonnet in front, but turned end for end, with its driving end forward.

Generally speaking, there are three methods of transmitting the power from a spring-suspended, centrally located differential gear to front driving wheels. One of them involves the transmission of the full wheel torque through shafts with universal joints at both ends, which shafts connect together, short shafts keyed into the differential side gears and the hub of the drive wheels, respectively. By the other two methods only a fraction of the wheel torque is transmitted through the transverse shafts, the torque being multiplied or stepped up by gearing directly at the wheel. In the one case the drive is through spur or internal gears, while in the other it is through two pairs of bevel gears, of which one driving and one driven gear form a unit rotating around the steering pivot axis. In the case of four-wheel drive trucks, where rather heavy torques have to be transmitted, these latter two methods have enjoyed a certain degree of popularity, but it seems likely that for passenger car drives an arrangement similar to the present rear axle drives will be used, the full speed reduction required being obtained by the gearing in the differential housing at the center of the axle and each axle shaft transmitting the full wheel torque. This latter arrangement seems to be preferable for high-speed vehicles because it represents a single reduction drive; a single reduction is all that is required in this type of vehicle, and is, of course, simpler and cheaper than a double reduction one. It is of particular importance in this connection that the weight saved, that of the reduction gears directly at the wheels, is unsprung weight.

A change from rear to front drive would confront the designing engineer with quite a number of new problems. It is directly apparent that front wheel drive Fig. 2. Itala front drive car would not fit in as well with modern six and eight-cylinder vertical engines as with the shorter types, such as four-cylinder and V engines. The engine would have to be placed a good deal further to the rear. In a conventional car of average size, in which the radiator is located over or slightly forward of the front axle, the distance from the center of the axle to the center of the most forward cylinder will be 8 or 9 in., which is about equal to the distance from the axis of the rear cylinder to the rear edge of the flywheel housing. In the front driven car, the engine would then have to be placed farther back by a distance equal to the length of the transmission gear, measured from the forward edge of its bell housing, plus the radius of the crown gear, if a bevel gear drive is used. The over-all length of the transmission would be about 12 in. and the distance from the back of the bevel pinion to the axis of the front axle 6 in.; hence the engine would have to be set some 18 in. farther back.

It is certainly not desirable to increase bonnet lengths over those now obtained with six- and eight-cylinder vertical engines, and this shows the advantage of using the shorter types of engine with the front drive. A slight shortening of the powerplant may be effected by the use of the worm drive, and this has been used in one or two designs in the past.

Problems of Design

The design of a front driving axle involves problems of considerable difficulty. Various solutions are possible, but it is not very apparent which of them offers the greatest advantages. One type of axle comprises a cranked or dropped carrying member, with a sufficient drop at the center so that it allows full spring play before the differential housing abuts against it. At the outer ends there must be swivel connections with the knuckles, and the axle end is made of the Elliott type, that is, there are two supports for the knuckle pin on the axle, instead of a single one. The reason for this is that the axle end must be formed with a hole through it concentric with the road wheel in the straight ahead position, through which the axle shaft can pass. The knuckle itself is made hollow, and a short shaft extends through it, which connects at its inner end with the axle shaft and at its outer end with the wheel hub through a jaw coupling, or it may be fastened directly into the wheel hub. If the short shaft has a bearing in the knuckle at its inner end, the axle shaft can float.

Instead of a drop axle, an arched axle may be used. This permits of hanging the powerplant lower without danger of inordinately reducing the road clearance. Such an axle, however, may make it more difficult to remove the powerplant from the chassis. Again, the cranked portion of the axle may be made horizontal and placed in front of the differential housing, as in the Miller front-drive racer, but in that case, moments are created which impose additional stresses on the master leaves of the chassis springs.

Designers of front-driven cars seem to have been particularly fascinated with the plan of doing away with a supporting axle and supporting the forward end of the chassis through the chassis springs directly on the steering heads. This scheme has the advantage of cutting down the total weight, as the springs are being made to do double duty; and the further advantage of improving the riding qualities and increasing the protection of the powerplant against shock, by decreasing the proportion of unsprung weight. It is sometimes objected to this construction that the wheel tread varies with the play of the springs and that, as a consequence, there will be side slip and wear of the tires. It would seem that with the comparatively small deflection of the front springs and increased lateral flexibility of balloon tires, as compared with the high-pressure type, this sideslipping of the tire treads can be entirely eliminated if the springs are made so they have no camber when under normal load. But in order to obtain a substantial connection between the steering heads and the chassis frame either three or four springs have to be used, (some of which can be replaced by rigid links.)

In other words, there must be connections to the steering head at two or more points a measurable distance apart in the fore and aft direction, to steady it against shocks in that direction, and also at two or more levels, to take care of the moment due to the reaction of the ground on the wheel and the lever arm represented by the distance from the center-plane of the wheel to the points of support of the springs on the steering heads. Forces in the fore and aft direction can also be taken care of by means of radius rods from the axle end to the frame, if that is preferred to doubling of the springs.

One method of driving front wheels is through two pairs of bevel gears of which the two intermediate ones form a unit that revolves around the knuckle pin axis. The first driving pinion is mounted on the axle shaft and the final driven gear on the wheel hub. The objection to this method is, of course, that it involves transmission through two extra pairs of gears to each wheel – eight bevel gears in all – with attendant waste of power and potentialities for causing noise.