An interesting and yet versatile summary of: the drivers and their after-race payments, the tyres and their race behaviour, the tyre rims, engine magneto’s, spark plugs, carburetors, axles and bearings and their functioning during race. Even the timing equipment, that was an after-race issue, is completely rehabilitated.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

THE HORSELESS AGE. Vol. 27, No. 23, June 7, 1911

Sport and Contests.

An Analysis of the Five Century Race.

Some Points and Side Lights on the Great Contest

Revision of Scores Showed Flaws in First Announcements

Twelve Cars Finished Full Distance Officially

Thirteen More Were Running When Flagged.

By M. Worth Colwell.

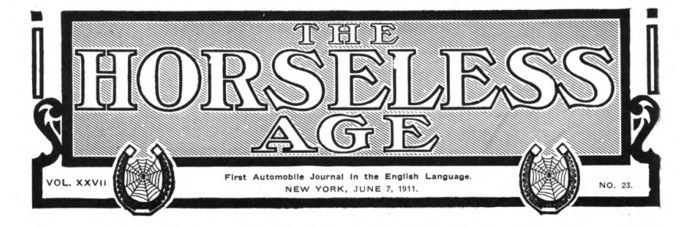

The last issue of THE HORSELESS AGE contained a graphic story of the great 500-mile race wired from the Indianapolis track by our staff of special correspondents, giving the account of the race in detail and also an exclusive story of the technical features and thrilling incidents noted at the pits by one of the technical committees. Since publishing that issue a revision of the scores altered the standing of the winners somewhat, the early announcements made by the officials being found to be in error in several cases when the contest committee checked up the records.

Most important in this work of revision was the fact that Dawson was awarded fifth place. sliding De Palma’s position back to sixth. It was thought at first that Dawson’s Marmon had broken down with a hole in its radiator, but the decision after careful investigation was that Dawson had actually covered the 500 miles, and was not signaled correctly on his final lap. It was a great consolation for the Marmon forces to not only win but also see their one other entry score a good fifth.

Other shifts in the score were: Merz (National) being switched to seventh place; the Amplex, driven by Turner and Jones, into eighth place; Belcher, the Knox pilot, getting ninth, and Cobe, who handled the Jackson, rewarded with the last prize position in the race, scoring tenth. The other cars who finished the full 500 miles were the Stutz, driven by Anderson, and the Mercer. piloted by Hughes. At first it was thought that Hughes had scored tenth place.

TWENTY-FIVE SURVIVED.

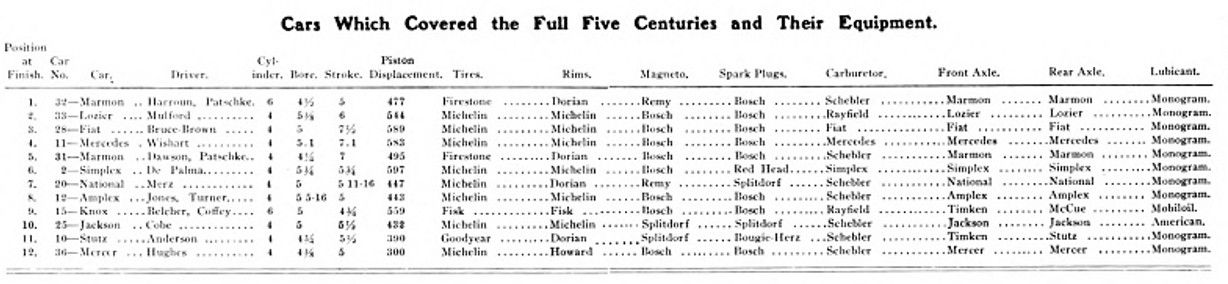

The survivors of the contest and the order of their finish are shown in the following table:

Diver and Car. Time. Miles Per Hour.

1-Harroun, Marmon. 6:42:08 74.8

2-Mulford, Lozier. 6:43:51 74.28

3-Bruce Brown, Fiat. 6:52:29 72.7

4-Wishart, Mercedes. 6:52:57 72.6

5-Dawson, Marmon. 6:54:37 72.3

6-De Palma, Simplex. 7:02:02 71.0

7-Merz, National. 7:06:20 70.3

8-Turner, Amplex. 7:15:56 68.0

9-Belcher, Knox. 7:19:09 68.3

10-Cobe, Jackson. 7:21:50 67.9

11-Anderson, Stutz. 7:22:55 67.7

12-Hughes, Mercer. 7:23:32 67.5

13-Frayer, Firestone-Columbus. Running.

14-Endicott, Inter-State. Running.

15-Fox, Pope-Hartford. Running.

16-Hearne, Fiat. Running.

17-Wilcox, National. Running.

18-Adams, McFarland. Running.

19-Delaney, Cutting. Running.

25-Bigelow, Mercer. Running.

21-Beardsley, Simplex. Running.

22-Hall, Velie. Running.

23-Endicott, Cole. Running.

24-Burman, Benz. Running.

25-Knipper, Benz. Running.

THE MONEY THEY MADE.

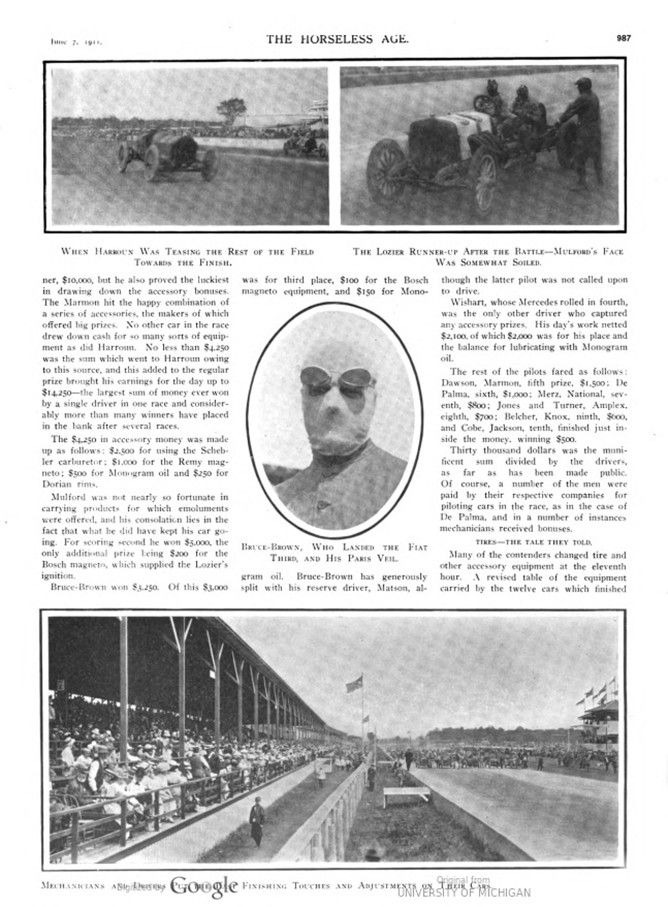

When it came to splitting up the money Harroun not only won the biggest cash prize offered by the Speedway for the winner, $10,000, but he also proved the luckiest

in drawing down the accessory bonuses. The Marmon hit the happy combination of a series of accessories, the makers of which offered big prizes. No other car in the race drew down cash for so many sorts of equipment as did Harroun. No less than $4,250 was the sum which went to Harroun owing to this source, and this added to the regular prize brought his earnings for the day up to $14,250 – the largest sum of money ever won by a single driver in one race and considerably more than many winners have placed in the bank after several races.

The $4,250 in accessory money was made up as follows: $2,500 for using the Schebler carburetor; $1,000 for the Remy magneto; $500 for Monogram oil and $250 for Dorian rims.

Mulford was not nearly so fortunate in carrying products for which emoluments were offered, and his consolation lies in the fact that what he did have kept his car going. For scoring second, he won $5.000, the only additional prize being $200 for the Bosch magneto, which supplied the Lozier’s ignition.

Bruce-Brown won $3.250. Of this $3,000 was for third place, $100 for the Bosch magneto equipment, and $150 for Monogram oil. Bruce-Brown has generously split with his reserve driver, Matson, although the latter pilot was not called upon to drive.

Wishart, whose Mercedes rolled in fourth, was the only other driver who captured any accessory prizes. His day’s work netted $2,100, of which $2,000 was for his place and the balance for lubricating with Monogram oil.

The rest of the pilots fared as follows: Dawson, Marmon, fifth prize, $1,500; De Palma, sixth, $1,000; Merz, National, seventh, $800; Jones and Turner, Amplex, eighth, $700; Belcher, Knox, ninth, $600, and Cobe, Jackson, tenth, finished just inside the money, winning $500.

Thirty thousand dollars was the munificent sum divided by the drivers, as far as has been made public. Of course, a number of the men were paid by their respective companies for piloting cars in the race, as in the case of De Palma, and in a number of instances mechanicians received bonuses.

TIRES – THE TALE THEY TOLD.

Many of the contenders changed tire and other accessory equipment at the eleventh hour. A revised table of the equipment carried by the twelve cars which finished the full 500 miles forms some interesting comparisons. The tale of the tires is that Firestones were largely responsible for Harroun’s victory, he having changed but four times on his right rear wheel the balance of the casings and tubes running the full five centuries without trouble. Dawson, who was awarded fifth place also had his mount shod with Firestones.

Michelin tires formed the cushions for the Lozier which was second, the Fiat in third place and Wishart’s Mercedes, which scored fourth. Sixth, seventh and eighth places, scored by De Palma (Simplex), Merz (National), and Jones and Turner (Amplex) went to the credit of Michelins. The same make was also on Cobe’s Jackson, the last car in the money, running tenth and also on Hughes‘ Mercer, in twelfth place. Belcher, who scored ninth after doing some of the fastest driving in the race, was the only contender using Fisks. Anderson had Goodyears.

The rim equipment on the placed cars was varied. Dorian triumphed on the winning Marmon, also on Dawson’s fifth best and the National, and Stutz, seventh and eleventh respectively – a splendid showing. On the other hand, Michelin rims were on one half of the first twelve cars. These were the Lozier, Fiat, Mercedes, running second, third and fourth; De Palma’s Simplex, sixth, the Amplex and the Jackson. Belcher used the Fisk rim, and Hughes had Howards on the Mercer.

While the Remy equipment scored a wonderful triumph in being Harroun’s choice, Bosch magnetos nevertheless made a great showing. Remy was credited with the winning place and seventh, Merz using it on his National. Bosch was found on all five cars from second to sixth place, also on the ninth, tenth and twelfth across the tape.

The Splitdorf equipped cars, while faultless in their ignition, had hard luck in smash-ups and accidents and among the placed cars the only ones using this make were Cobe’s Jackson and Anderson’s Stutz.

It was most interesting and delightfully satisfying to the Remy forces to know that in every case where one car of a team used Remy and the other members of the team another make, the Remy fitted car was the one to make a showing, outdistancing its competitors.

The spark plug situation was almost a clean sweep for Bosch. The first five cars had this make, also the eighth, ninth and twelfth. De Palma banked on Red Heads in his sixth best Simplex. The National in the seventh notch and Cobe’s Jackson used Splitdorf.

A great showing was made by Schebler carburetors. Aside from being the lucky choice of the „Wasp“ pilot, Scheblers were found on Dawson’s Marmon in the fifth place; Merz’s National, seventh; the next best Amplex, the Jackson in tenth place, the Stutz, eleventh, and the Mecer, twelfth.

Axles for the most part were factory equipment; that is, they bore the name of the car of which they formed a part. The Harroun Marmon, Lozier, Fiat, Mercedes, Dawson Marmon, Simplex, National and Amplex, which finished in that order, used their own axles, while Belcher’s Knox had a Timken front and a McCue rear. The Stutz used a Timken front, while the rear was the unique axle of Harry Stutz’s own design. Stutz entered his car chiefly to demonstrate the efficiency of his axle, and was rewarded by seeing the car make good. Unfortunately, many tire changes necessitated much loss of time at the pits. The Jackson and Mercer used their regular factory axles.

The bearings on the victorious „Yellow Jacket“ were the products of the Timken Roller Bearing Co. as far as the front wheels and differential were concerned, while Schafer ball bearings were used on other parts of the car.

MOST OF THEM „GREASED“ WITH MONOGRAM.

As ‚for lubrication-ah, that important factor ! – it was a Monogram holiday! Not a single one of the elect complained of lubrication difficulties, and it was Monogram which was found on ten of the twelve which finished. To the credit of Mobiloil, it must be said that Belcher used this, and he never lifted the bonnet once, while Cobe used American lubricants in the Jackson and had no trouble in this respect. On the whole, throughout the race there was hardly a complaint which could be traced to lubrication difficulty, which not only demonstrated the excellence of the lubricants used, but also the efficiency of the oiling systems.

One thing was noticeable throughout the race. Drivers and mechanicians did not overlubricate as much as has been the case in some races. There was not nearly the amount of dense smoke shooting from the exhausts of most of the racers as might have been.

ON THE WHOLE ACCESSORIES BEHAVED WELL.

Many of the contenders who did not score places, but did notably while running or until accident eliminated them, were a credit to the concerns whose equipment they carried, just as the equipment was a credit to their cars. The mere fact that a large number failed to cover the full five hundred miles does not mean that the equipment carried failed to work as it should. Of course, tire trouble held many back, but the fact that all makes entered had trouble with blown out and burned casings proved that it was the high speed and the warm bricks and banking of the course which was responsible, rather than inferiority of the rubber tubes and casings.

It is true that bursting tires caused some of the accidents, and had not such doughty contenders as Disbrow’s Pope „Hummer,“ Tetzlaff’s Lozier, Lytle’s Apperson, Greiner’s Amplex, Knight’s Westcott and the trio of small but speedy Cases been eliminated by smash-ups, the tale of the winners would have read differently. If-if-if -!

HOW THE DRIVERS STOOD THE GRIND.

The way the drivers stood the long grind was remarkable. Mulford, De Palma, Bruce-Brown and Hughes, who were placed at the finish, drove the entire 500 miles without relief at the wheel. During the last hundred miles De Palma appeared tired, but stuck grimly to the wheel. Bruce-Brown finished apparently as fresh as when he started, while Mulford appeared somewhat stiff when he alighted from his car for the last time. Harroun took a rest for nearly two hours while Patschke drove the „Wasp,“ and the „Bedouin“ said he was glad he took the rest for it made him better able to stand the strain at the finish. While at the wheel Patschke drove for the most part faster than Harroun, and great credit is due the younger driver for the way he helped the „Wasp“ to victory.

Some of the pilots appeared „all in“ each time they were relieved.

SCORERS‘ LOT NOT A HAPPY ONE.

That there was a mix-up in the scoring of the race was unfortunate, hut those in charge must not be blamed for it. All of the officials, timers and scorers-experts in every case-did their level best. The system planned, however, did not work as expected, merely because the cars were so numerous and tore around so fast. Harry Knepper, who was one of the timers, explained the situation upon his return East as follows:

„There was no trouble with the timing at the Indianapolis race, and the delay in announcing the final results of the race was due to the system of scoring, which before the race looked good in theory, but failed to work out in practice. As arranged by the Indianapolis management, there were seven different and distinct men scoring the race.

„First – Four adding machine men were employed, who recorded the cars as they passed the stand. These men and their machines were stationed in four different places: that is to say, one was in the judges‘ stand, one in the timers‘ stand, one in the press stand and another in the grandstand, and each of these men had an expert automobilist to call out each of the cars as they passed.

„Second – Two dictographs were used and a man talked the numbers into them as the cars passed by.

„Third – I had a man call the numbers to me in the timers‘ stand and verified them myself, and called out the leading cars to Charlie Warner, who inserted the numbers on the timing tape.

„The numbers were handed to a sheet man, and he was supposed to check them on to a score sheet, but these numbers came so fast that it was impossible for him to keep the cars checked up properly, which fact caused all the trouble at the finish.

As a result, after the race the officials had to take the records made by the adding machines and the dictographs and check them up with the timing record made by Mr. Warner and myself.

„As over six thousand cars crossed the line during the race, this took time, and the officials worked continuously from the conclusion of the race until 7 o’clock on Thursday morning before the final records were complete.

„We also made a record of each car, with its time, at the end of the 10th, 20th. 40th, 6oth. 80th, 100th. 150th and 200th lap and gave the position of each car at this particular period of the race. Then we took groups of four or five cars and went all over the records on the tape, which was over a mile long, to see that the cars checked up, with the proper number of laps. While this took time, we had at the conclusion four records of each car, which in every case checked up properly with the record, and on this record the final awards were based.

„In future races I would like to suggest that the scoring be done automatically by a machine which has been devised by Mr. Wagner, as the Indianapolis race has proved that it is impossible for the human eye and hand to keep these records up to date and announce accurately at the conclusion of the race the position of the cars, without having the whole system rechecked, which takes considerable time.

„Contrary to reports sent from Indianapolis, the timing machine did not break down at all, but the mechanical wire across the track did; but this in no way interfered with the proper timing of the race, as the machine was operated by a hand trap while the repairs were being made. It is not surprising that the steel wire across the track did snap, as it was hit something like six thousand times by the force of a ton or more flying along at 80 or 90 miles an hour, and the pressure was so great that it cut a groove half an inch thick right through the brick surface of the finish line.

„I would suggest that in future races the starting line and timers‘ stand should be so placed that the cars would have to pass the timers‘ stand or scorers‘ stand before going to the pits for supplies or tire repair, which would eliminate all possible chance of a car crossing the line and hacking up to the pits and being scored a second time, which is a possibility under the present system.“

RACING IS NOT „DOOMED.“

It was the opinion of certain persons, who believed themselves well informed that the future of automobile racing hung in the balance as those forty cars lined up for the great speed battle. Numerous wiseacres predicted that the contest would be the death-knell of racing for all time, and that the contest would prove a detriment to the industry.

It seems they were all wrong. THE HORSELESS AGE did not believe any such nonsense for various reasons. One was that the Indianapolis Speedway is the safest course in America for such high-powered cars. Another reason was that makers for the most part had sufficiently strong cars to stand the test without falling to pieces; another was that the officials ruled off in practice certain drivers who appeared incompetent; another was that most of the drivers, realizing the conditions of the event, planned not to drive recklessly.

Racing of the speedier sort never will die in America while handled properly. This is in spite of what certain persons whose connection with racing has not proven lucky say when they deal alleged „blows“ to racing. Those individuals should have seen the eighty odd thousand spectators who went wild with enthusiasm almost every minute of the contest on Memorial Day.

Photo captions.

Page 986 – 991

THE VICTOR, JUST AFTER THE FINISH – TRYING TO SMILE MODESTLY.

JUST PRIOR TO THE START OF THE GREAT 500 MILE JOURNEY, IT WAS INTERESTING TO WATCH THE MECHANICIANS AND DRIVERS PUT THE FINISHING TOUCHES AND ADJUSTMENTS ON THEIR CARS.

WHEN HARROUN WAS TEASING THE REST OF THE FIELD TOWARDS THE FINISH.

THE LOZIER RUNNER-UP AFTER THE BATTLE – MULFORD’S FACE WAS SOMEWHAT SOILED.

BRUCE-BROWN, WHO LANDED THE FIAT THIRD, AND HIS PARIS VEIL.

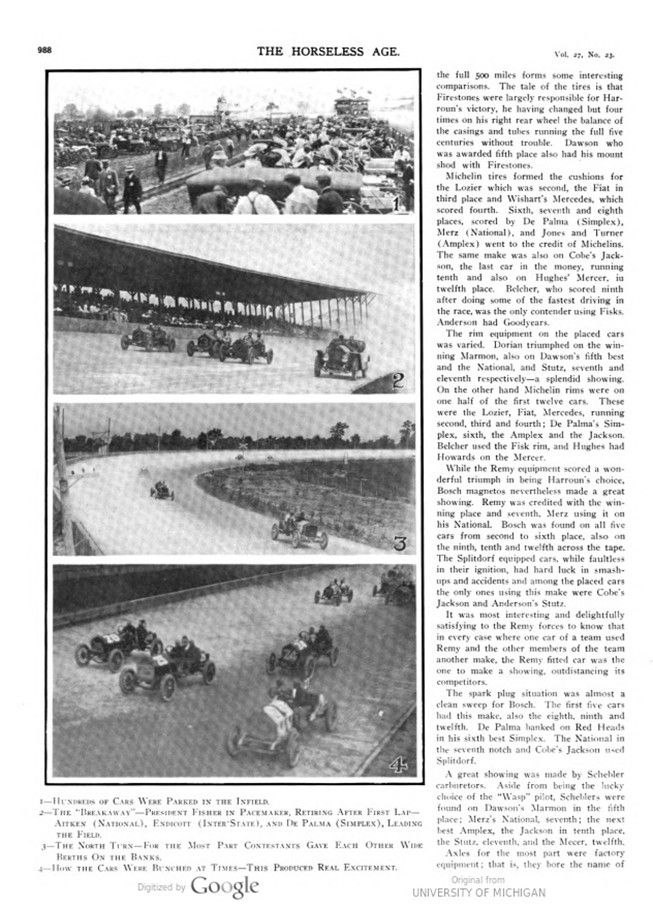

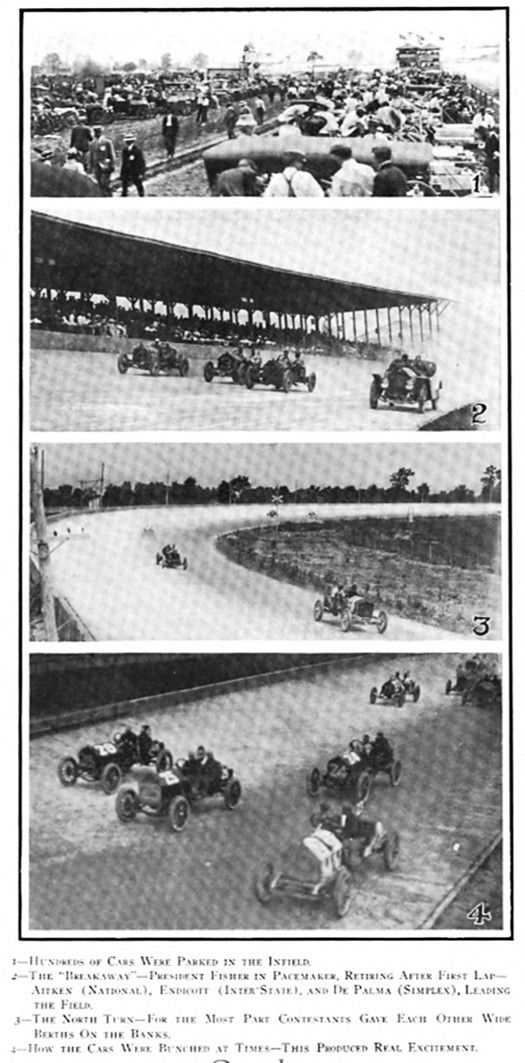

1 – HUNDREDS OF CARS WERE PARKED IN THE INFIELD.

2 – THE „BREAKAWAY“ – PRESIDENT FISHER IN PACEMAKER, RETIRING AFTER FIRST LAP – AITKEN (NATIONAL), ENDICOTT (INTER STATE), AND DE PALMA (SIMPLEX), LEADING THE FIELD.

3 – THE NORTH TURN – FOR THE MOST PART CONTESTANTS GAVE EACH OTHER WIDE BERTHS ON THE BANKS.

4 – HOW THE CARS WERE BUNCHED AT TIMES – THIS PRODUCED REAL EXCITEMENT.

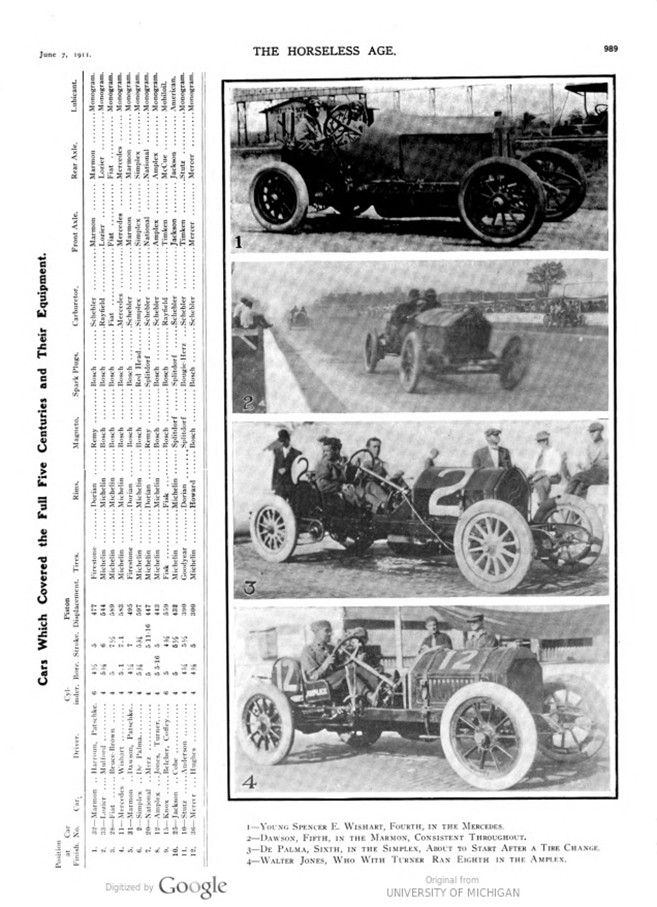

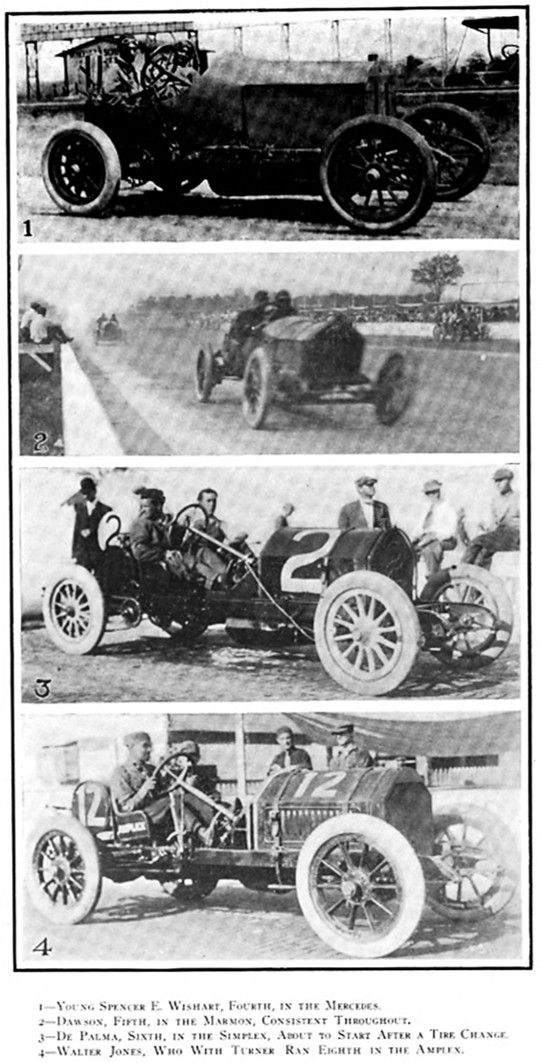

1 – YOUNG SPENCER E. WISHART, FOURTH, IN THE MERCEDES.

2 – DAWSON, FIFTH, IN THE MARMON, CONSISTENT THROUGHOUT.

3 – DE PALMA, SIXTH, IN THE SIMPLEX, ABOUT TO START AFTER A TIRE CHANGE.

4 – WALTER JONES, WHO WITH TURNER RAN EIGHTH IN THE AMPLEX.

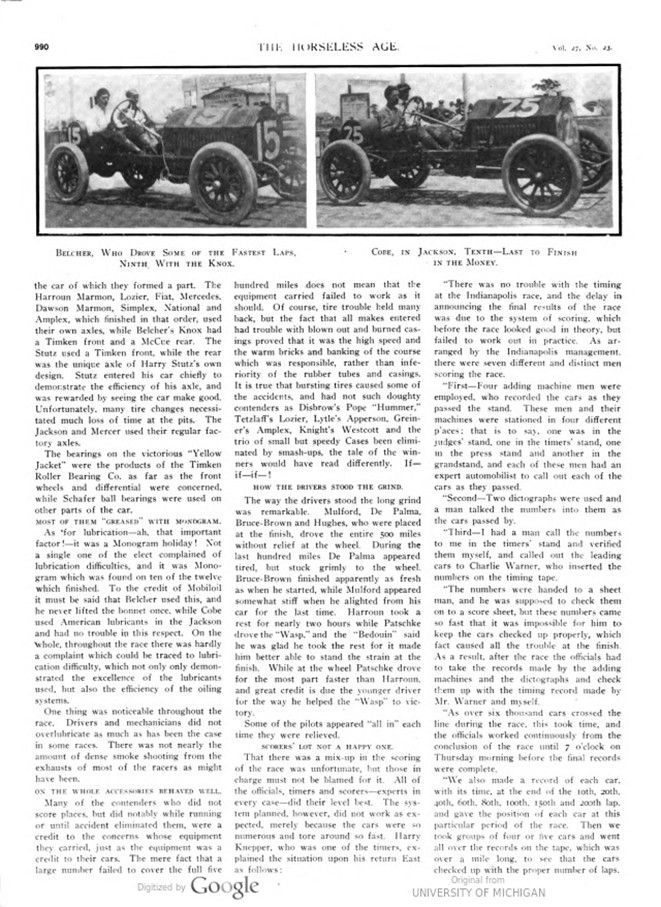

BELCHER, WHO DROVE SOME OF THE FASTEST LAPS, NINTH, WITH THE KNOX.

COBE, IN JACKSON, TENTH – LAST TO FINISH IN THE MONEY.

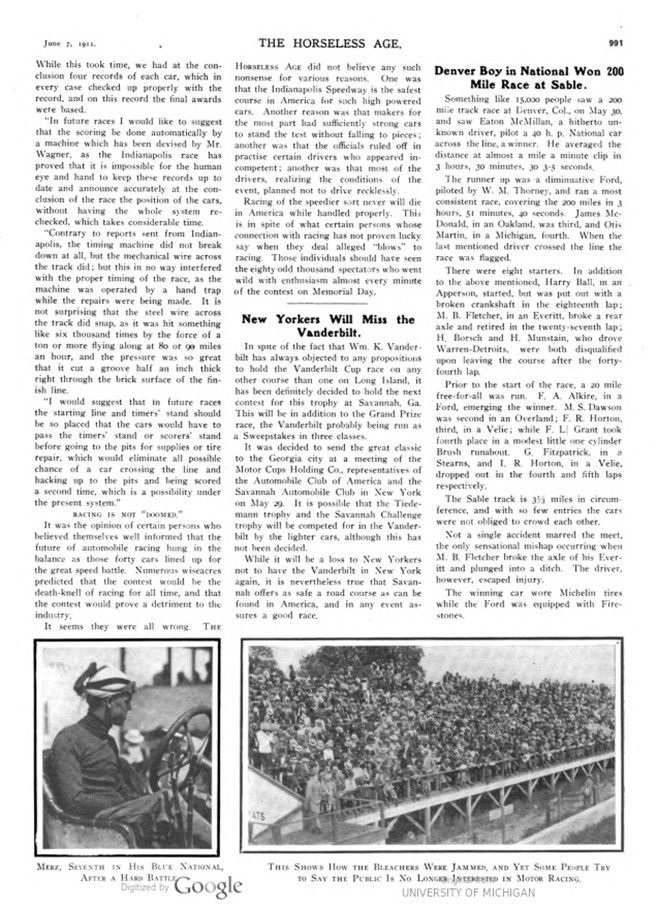

MERZ, SEVENTH IN HIS BLUE ATIONAL, AFTER A HARD BATTLE.

THIS SHOWS HOW THE BLEACHERS WERE JAMMED AND YET SOME PEOPLE TRY.

TO SAY THE PUBLIC IS NO, LONGER INTERESTED IN MOTOR RACING.