Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Automobile Journal, Vol. LXVIII, 67, No. 11, June 1920

American Car Wins Eighth International Sweepstakes at Indianapolis

Gaston Chevrolet in Monroe Special Carries Off Premier Honors in 500-Mile Race May 31.

IN THE presence of nearly 125,000 automobile race enthusiasts, and with no serious accidents to mark a contest that, particularly toward its close, was not without its thrilling incidents and tense moments of excitement. Gaston Chevrolet won victory at the Eighth International 500-Mile Sweepstakes, at Indianapolis, Ind., Monday, May 31, in a Monroe Special, an American-made car designed by Louis Chevrolet, an older brother of the daring and skillful young French driver.

For the third time in the history of this famous motor Derby, the premier honors have been secured by a car made in this country, the previous American winners being a Marmon, driven by Ray Harroun, in 1911, and a National, piloted by Joe Dawson, the year following. And it was particularly a triumph for Indianapolis in that all these winning American cars were built in the city where this famous motor classic is held.

The race itself was considered by experts to be, beyond all question, the best contested that has ever been witnessed. It was throughout a test of skillful driving and generalship, but so far as spectacular features were concerned, these were conspicuous by their absence until the later part of the race. There was no great belching of black exhausts, none of the deafening roar of former contests, and but little work at the pits.

Story of Race.

The story of the race in brief was as follows: The field of 23 starters made rather a ragged get-away, being well strung out. De Palma had barely crossed the tape when he had to stop for a look at his motor. While he was at the pit, Joe Boyer in his Frontenac, Gaston Chevrolet in a Monroe, Art Klein in a Frontenac and Jean Chassagne in a Ballot set the early pace well in advance of the rest of the field.

There was little change in positions up to the 50-mile mark. At this point Boyer and his team mate were leading, with the Frontenacs, with Chassagne in third place and Gaston Chevrolet in fourth position. By this time De Palma had got into the game again and had picked up one after another of the cars in front of him until he encountered Boyer. Then, for lap after lap, came a series of brushes in the long grand stand stretch, with some hair-raising bursts of speed between these two daring drivers on the turns. For at least 50 miles they alternated in the lead with the rest of the field far behind. It was simply a test of skill and speed between them.

De Palma Ahead at 100 Miles.

At the 100-mile mark De Palma had a slight advantage but, on the very next lap, Boyer took the lead once more. Chassagne was in third place. They were reeling off the miles at the rate of 93 an hour.

At 125 miles Boyer and De Palma were still battling for supremacy, and Chassagne was still in third place with Gaston Chevrolet at his heels.

The first important break in the leadership in the race came when De Palma, after covering 192 miles, pulled up for a change in tires. He also took on oil, gasoline and water, and this delay gave Boyer a big advantage, of which he continued to make the most. When De Palma ran in again, he had a whole lap to make up on Chassagne and Hill. The field began to dwindle, among the star performers who were forced to quit being Wilcox, Andre Boillot and Jules Goux, driving Peugeots.

There were only 16 cars left in the race at the 200-mile post with Boyer still in the lead. Rene Thomas moved up De second place. Palma soon recovered into much of his lost ground and moved up to third place, with the others in the following order: Gaston Chevrolet, Chassagne, Arthur Chevrolet, Milton, Murphy and Henderson. When Gaston Chevrolet turned his 250 miles he was forced to make a stop, making Thomas all the more secure in second place. Boyer made his first stop for oil and gasoline after he had covered 260 miles. This cost him the lead. Thomas moved up into first place, with De Palma and Boyer fighting it out once more, this time for second place. Thomas‘ lead was short lived, however, as he had to pull up for tires, oil and gasoline.

De Palma Returns to the Lead.

This gave De Palma the lead and the early struggle between him and Boyer was renewed, being the feature of this stage of the race. At about the 325-mile post Boyer had to slow up for a change of tires, and this placed De Palma securely in first place, which he held, and at 375 miles he had a comfortable lead of two laps over Gaston Chevrolet and three over Thomas and Chassagne, with Boyer in fifth place. Barring accident, it began to look like De Palma’s race. Boyer was forced to make another stop just as De Palma reeled off his 400th mile, but Gaston Chevrolet, Thomas and Chassagne were still going strong.

At this stage De Palma electrified the spectators by making a right rear tire change in exactly 15 seconds. The slight stop did not affect his standing, and he was still in the lead by a margin of a couple of laps over Gaston Chevrolet at the 450-mile mark. Then with a lead of five miles and only 33 miles to go, he met with disaster by running short of gasoline on the back stretch, a mile and a half away from his source of supply. This bit of hard luck cost De Palma the race, as Gaston Chevrolet had no difficulty in moving up into first place, which he held to the end despite the fact that he, too, had to stop to take on fuel, but he ran short nearly in front of his pit and lost but little time.

Interesting Features.

Among the interesting features in connection with this eighth international contest may be noted the fact that of the 23 starters, there was but one six-cylinder car, which was built several years ago; that 10 were of eight-cylinder de- sign, in a line, and the remaining 12 had four-cylinder motors.

All the competing cars, except the six- cylinder, were new designs that had never before competed in a race. The cylinder displacement was decidedly below that of previous years and the cars themselves seemed miniature reproductions of the big speed cars of former races. Yet up to the 470th mile, when De Palma met his reverse, the average speed of the contest was far above the record. That in itself speaks for the speed ability of the cars. But there is still a greater reason in favor of cars of this type that of safety to the contestants. There was not a serious accident during the entire race, a record almost unparalleled in the Indianapolis 500-mile event, and one which should contribute greatly to the success of such contests.

The purse, $85,000, was the largest ever offered in a motor car competition. Speed stars of four nations were represented, United States, England, France and Italy, the Big Four among the allies of the recent world war, who now met in strenuous rivalry for the world’s premier racing honors.

There were three four-car teams, the Peugeot, Monroe and Duesenberg; Ballot and Frontenac cars were represented by three cars apiece, and Gregoire and ReVere by two cars each. The Peugeots, Ballots and Gregoires are French cars, giving that country nine representatives.

Another interesting point concerning equipment was that seven of the first 10 cars to finish had Delco ignition, magneto ignition being used on the three French cars finishing.

Career of Winner.

Gaston Chevrolet, the winner of this year’s speedway race, is the youngest of the famous racing brothers, one of whom, Louis, is the designer of the Monroe Special car, which won the race. Previous to last year Gaston Chevrolet had achieved slight fame as a speed driver. He broke the world’s record for the 100-mile mark in competition when he won the 100-mile free-for-all Independence Day race at Sheepshead Bay last season with an average speed of 110.5 miles an hour. Later in the year he made an average of 108.95 miles an hour over the same track when he won the 150-mile Labor Day event. Teaming with Joe Boyer he won the 225-mile race at the Uniontown track and was sixth in the list of drivers in all races for the year. He showed marvelous driving ability in the 1919 Indianapolis race when he was neck and neck with Ralph De Palma and his brother, Louis Chevrolet, until at the climax the wheel of his machine snapped off and he dropped back to eighth place. His first race was in 1916 on the speedway, but he had mechanical trouble and did not finish. In 1917 he teamed with Louis Chevrolet and Joe Boyer in Frontenacs and scored third place in the Cincinnati 300-mile race. He also won two seconds and a third in the short races at Chicago.

Prize Money.

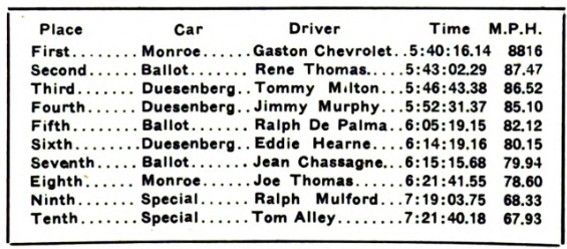

The prize money, $100 a mile, $50,000, was divided among the first 10 to finish, as follows: $20,000, $10,000, $5000, $3500, $3000, $2200, $1800, $1600, $1500. Lap prizes: $100 a lap, $20,000, awarded by Indianapolis business men and manufacturers to leaders during race. Accessory prizes: $15,000, awarded by manufacturers of automobile accessories to winners using their product.

Facts in Regard to Speedway.

Length of course, 2½ miles; area of speedway, 328 acres; capacity of parking space, 10,000 cars; total estimated capacity, 200,000 spectators; greatest previous attendance, 110,000 spectators in 1914; capital invested, $1,500,000.

Owners and management: President, Carl G. Fisher; vice president and treasurer, James A. Allison; vice president, A. C. Newby; secretary and general manager, T. E. Myers, all of Indianapolis.

Race officials: Referee – Hon. Clifford Ireland, United States Congressman, Peoria, Ill. Starters – William Esterly, Indianapolis; E. C. Patterson, Chicago. Chief timer – Chester Ricker, Indianapolis. Representatives of contest board, American Automobile association – W. D. Edinburn, Detroit, Mich.; W. C. Barnes, Peoria, Ill. Pacemaker – Barney Oldfield, Cleveland.

Present record, established by Ralph De Palma in 1916, time, 5:33:55.51, an average of 89.84 miles an hour.

Facts Regarding Previous Races.

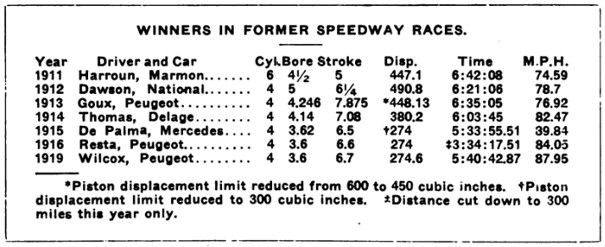

Seven races have been run in the 10 years that the Indianapolis speedway has been in existence, there being no international races in 1918 and 1919, on account of the war.

1911 – The first race, this year, was won by Ray Harroun in a Marmon Wasp in one of the most spectacular finishes on record, flashing over the wire only one minute and 43 seconds ahead of Ralph Mulford in his Lozier, with Bruce-Brown in a Fiat third; Wishart, Mercedes, fourth; Dawson, Marmon, fifth; De Palmer, Simplex, sixth; Merz, National, seventh; Turner, Amplex, eighth; Belcher, Knox, ninth; Cobe, Jackson, 10th; Anderson, Stutz, 11th; Hughes, Mercer, 12th. The winning time was 6:42:08 and the average rate was 74.59 miles an hour. There was one fatality and several minor accidents.

1912 – The race for 1912 is known by those who have followed up these events as the Jinx year for Ralph De Palma for, in next to the last lap, with a lead of more than 11 minutes, his Mercedes developed engine trouble and the race was easily won by Joe Dawson in a National. There were no fatalities. Dawson’s time was 6:21:06, and the average rate was 78.7 miles an hour. The other money takers were: Tetzlaff, Fiat; Hughes, Mercer; Merz, Stutz; W. Endicott, Schacht; Zengel, Stutz; Jenkins, White; Horan, Lozier; Wilcox, National; Mulford, Knox.

1913 – The season of 1913 marked the beginning of the invasion of European cars, and the race went to Jules Goux in a Peugeot. There was some consolation in the fact that the winning time of 6:35:05 was nearly 14 minutes slower than Dawson’s the previous year, the average rate per hour, 76.42 miles, also being 1.78 miles less, and that second and third places were taken by American cars. The piston displacement limit was lowered this year from 600 cubic inches, which ruled for the first two races, to 450 cubic inches. The drivers and cars in the order they finished, were as follows: Goux, Peugeot; Wishart, Mercer; Merz, Stutz; Guyot, Sunbeam; Pilette, Mercedes-Knight; Wilcox, Gray Fox; Mulford, Mercedes; Disbrow, Case; Haupt, Mason; Clark, Tulsa.

1914 – America was completely out of the running in the spectacular race of 1914 when Rene Thomas in a French-built Delage, set a new record of 6:03:45, nearly four miles an hour better than the old record held by Joe Dawson’s National. The average rate per hour made by Thomas was 82.47 miles. This race was, from start to finish, a duel between teams representing two French manufacturers, Peugeot and Delage, and the rivalry was intense. This year was marred by an unfortunate accident which marked the end of Joe Dawson’s career as a racing driver. In trying to avoid running down a mechanician who had been hurled on to the track, Dawson crashed his car into the embankment and suffered serious injuries. The cars finished this year in the following order: Thomas, Delage; Duray, Peugeot; Guyot, Delage; Goux, Peugeot; Oldfield, Stutz; Christiaens, Excelsior; Grant, Sunbeam; Keene, Beaver Bullet; Carlson, Maxwell; Rickenbacher, Duesenberg.

1915 – It was not until this year that De Palma became consoled for his misfortune of 1912 by winning first money in 5:33:55.51, at the average rate of 89.84 miles an hour. His greatest rival was Dario Resta, who had already won the Vanderbilt and Grand Prix races, and they were close together throughout the race until within a few laps from the finish trouble developed in the steering gear of Resta’s Peugeot and De Palma had a comparatively easy victory.

Although the piston displacement limit for the 1915 race had been reduced from 450 to 300 cubic inches, not only did De Palma break the previous years‘ records, but the next three cars did, likewise, all finishing in faster time than Thomas‘ old mark. The achievement of the Stutz team this year is also worthy of mention inasmuch as all three entries finished in the money. The order of the cars at the finish was as follows: De Palma, Mercedes; Resta, Peugeot; Anderson, Stutz; Cooper, Stutz; O’Donnell, Duesenberg; Burman, Peugeot; Wilcox, Stutz; Alley, Duesenberg; Carlson-Hughes, Maxwell; von Raalte, Sunbeam.

1916 – this year the length of the Indianapolis speedway classic was reduced to 300 miles. Dario Resta won it in a Peugeot without any serious opposition from the rest of the field participating. He made the 300 miles in 3:34:15.71, considerably slower, judged on an average miles-per-hour basis, than that in which De Palma had won the 1915 race. The effects of the war were manifested in the lack of interest and the fact that the cars entered were below the standard of previous years, there being virtually no new machines in the race. The drivers and cars were: Resta, Peugeot; D’Alene, Duesenberg; Mulford, Peugeot; Christiaens, Sunbeam; Oldfield, Delage; Henderson, Maxwell; Wilcox, Premier; Johnson, Crawford; Chandler, Crawford; Haibe, Osteweg; Alley, Ogren.

1919 – After a lapse of two years the 500-mile race was resumed at Indianapolis and while, from the viewpoint of interest and attendance it was a big success, and from a feeling of satisfaction that its winner was an American, Howard Wilcox, as a racing achievement it could not be considered an unqualified triumph. In the first place, with the exception of the Ballot French team of three cars, the entries were all several seasons old and most of them were slow as compared with the offerings of the palmier days of the sport. Had it not been for wheel and tire troubles at critical times the Ballot team would undoubtedly have given a good account of itself. As it was, the moment they were out of the running, Wilcox, in his Peugeot, realized that he had an easy win. There were four fatalities. The winner’s time was 5:40:42.87, and the average rate 87.95 miles an hour.

Time for 1920 Slower Than 1915.

It will be noted that while the time this year, 5:40:16.14, was somewhat faster than that made in 1919, it did not reach the 1915 mark by six minutes and 21 seconds, and the average miles per hour, made in 1915, was 1.68 more than this year.

Indianapolis, during the 10 years‘ existence of its famous motor speedway, has seen the progress of automobile engineering concentrated within its borders during that decade. In these annual international races that have been so successfully staged in the Hoosier capital city can be traced the gradual development of the multi-cylinder engine, and the growing strength of the light weight car. Europe, through the participation of the best and speediest products of that continent, driven by its most daring and skillful pilots, has benefited mutually with this country, in the trying out of the ‚most advanced designs in motor car construction year after year in the gruelling test of the 500-mile race at record speed.

Thus it will be seen that the mission of the Indianapolis speedway has been not alone to lead the world of sports in point of attendance and interest; it has also served the industry as a clearing house for the interchange of ideas and the exemplification of ideals among the most famous automotive engineers of the world in the interest of progress in the design, manufacture and equipment of the automobile.

Photo captions.

Page 9.

Gaston Chevrolet, Winner of Eight International 500-Mile Sweepstakes at Indianapolis, May 31.

Page 10 -11.

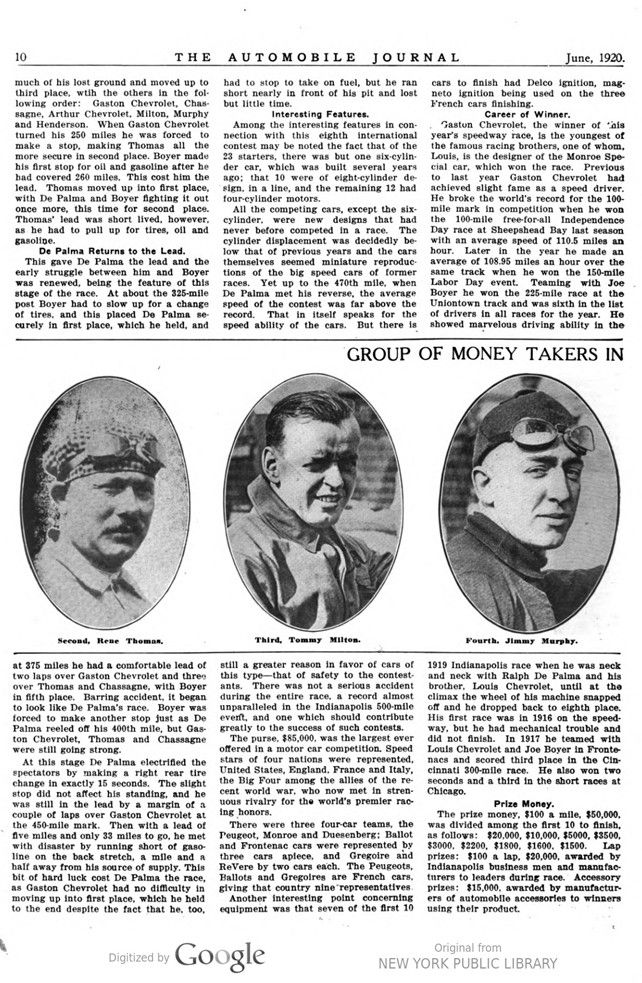

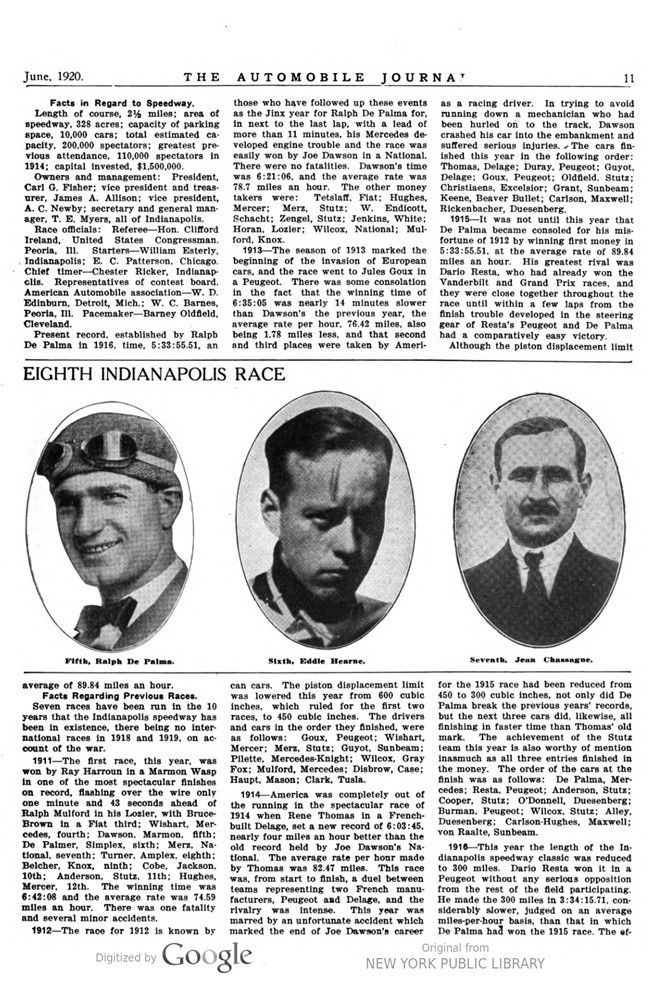

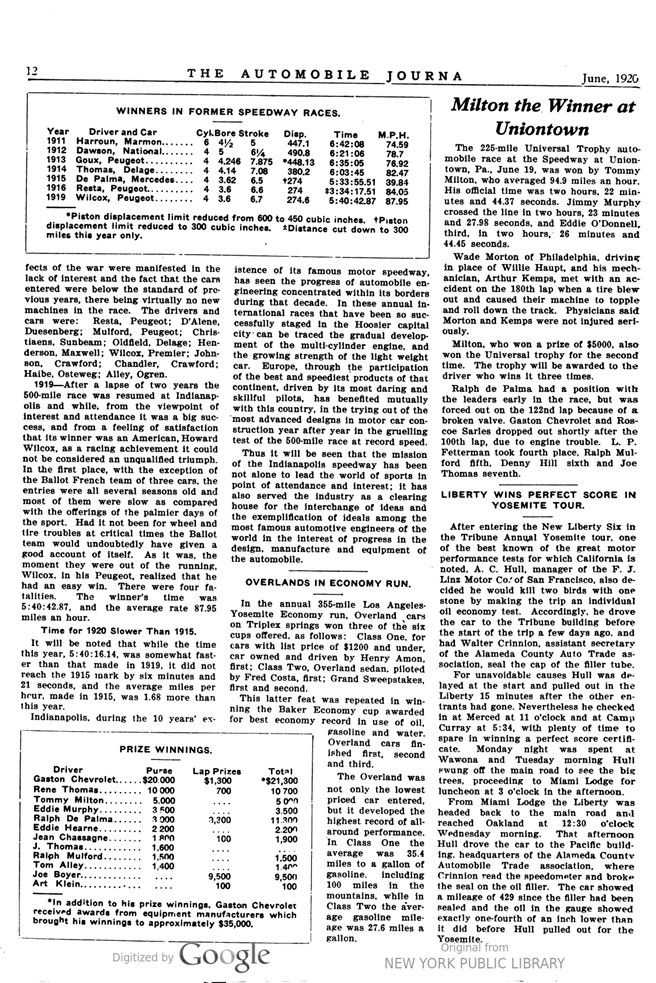

GROUP OF MONEY TAKERS IN EIGHTH INDIANAPOLIS RACE

Second, Rene Thomas. Third, Tommy Milton. Fourth, Jimmy Murphy. Fifth, Ralph De Palma. Sixth, Eddie Hearne. Seventh, Jean Chassagne.

Page 12.

WINNERS IN FORMER SPEEDWAY RACES.

*Piston displacement limit reduced from 600 to 450 cubic inches. Piston displacement limit reduced to 300 cubic inches.

*Distance cut down to 300 miles this year only.

PRIZE WINNINGS.

*In addition to his prize winnings, Gaston Chevrolet received awards from equipment manufacturers which brought his winnings to approximately $35,000.