A Lively report from the 1915 Sweepstakes, with a thorough race analysis, a technical analysis and kind of financial analysis. This year, valve head engine seemed to make a breaktrough, as 15 out of 24 cars used overhead valves. Mechanical failures also reduced in comparison to earlier years; and many more different carburetor brands were used. The Stutz cars performed very well. And although entrance fees were doubled this year, it didn’t seem to have any influence on spectator counts.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

The Automobile Journal, Vol. 39, No. 9, June 10, 1915, page 17-23

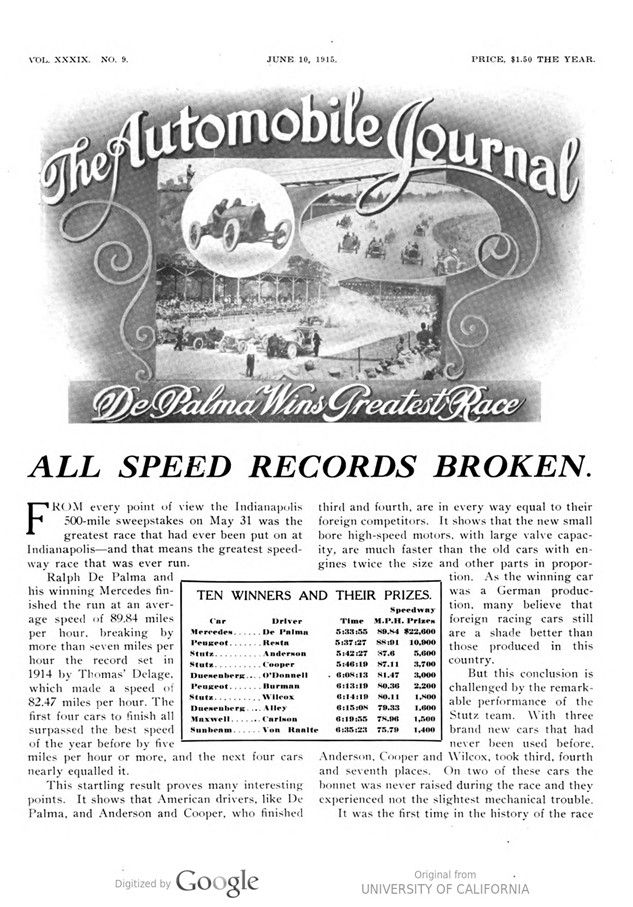

De Palma Win’s Greatest Race

ALL SPEED RECORDS BROKEN.

FROM every point of view the Indianapolis 500-mile sweepstakes on May 31 was the greatest race that had ever been put on at Indianapolis-and that means the greatest speed- way race that was ever run.

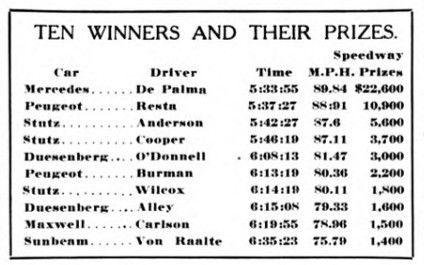

Ralph De Palma and his winning Mercedes finished the run at an average speed of 89.84 miles per hour, breaking by more than seven miles per hour the record set in 1914 by Thomas‘ Delage, which made a speed of 82.47 miles per hour. The first four cars to finish all surpassed the best speed of the year before by five miles per hour or more, and the next four cars nearly equaled it.

This startling result proves many interesting points. It shows that American drivers, like De Palma, and Anderson and Cooper, who finished third and fourth, are in every way equal to their foreign competitors. It shows that the new small. bore high-speed motors, with large valve capacity, are much faster than the old cars with engines twice the size and other parts in proportion. As the winning car was a German production, many believe that foreign racing cars still are a shade better than those produced in this country.

But this conclusion is challenged by the remarkable performance of the Stutz team. With three brand new cars that had never been used before, Anderson, Cooper and Wilcox, took third, fourth and seventh places. On two of these cars the bonnet was never raised during the race, and they experienced not the slightest mechanical trouble. It was the first time in the history of the race that three cars of any team, American or foreign, all won places. Stutz, this year, as last, was the first American car to finish. In the four races in which it has competed it has won seven places, another unbeaten record for consistent performance.

Though they came through the race without the least mechanical trouble, Anderson, whose average speed was 87.62 miles per hour, and Cooper, who made the course in 87.11, lost a great deal more time on account of tire changes than De Palma and Resta. These latter stopped at the pits only twice during the race. De Palma consumed three minutes and 23 seconds at the pits and Resta, three minutes and 19 seconds.

Anderson, on the other hand, was forced to make eight stops for tires and fuel, which cost him seven minutes and two seconds, while Cooper lost five minutes. Wilcox, whose Stutz was seventh, with a speed of 80.11 miles per hour, ran most of the race on three cylinders.

Conditions at the track were never more favorable and it is the judgment of experts that many years are likely to pass before the record set is again broken. It had rained a great deal at Indianapolis the week before the race, which had to be postponed on that account from Saturday, May 29, to Monday, May 31. The day opened with overhanging clouds. For that reason the bricks were cool and not so hard on tires as they often are, and the absence of bright sunlight removed the blinding glare of the bricks from the drivers‘ eyes, so that they could see perfectly and do their best.

The most thrilling feature of the race to the crowd of about 75.000 persons who were present, was the desperate duel between De Palma and Resta. Dario Resta, skillful, determined, fresh from his victories in the Grand Prize and the Vanderbilt Cup, fought constantly to take the lead. At one time he skidded into the speedway wall and loosened his steering gear, so that he found it necessary to reduce his speed slightly or the result might have been different.

DePalma’s Skill on Corners.

His Peugeot seemed to be slightly faster on the straight away, but De Palma’s finished skill in rounding the corners and his quick pick-up gave him the advantage on the turns. De Palma was in one of the rear rows at the start and it was only after 350 miles of constant struggle for position that he emerged in the lead and managed to hold it.

At the start of the race Resta, who was in the front row, took the pace, but held it for only one lap, when Wilcox in his Stutz went by him. He kept it for 10 miles and then Anderson shot in front and held the lead against all pursuers for 70 miles of furious driving. At 82 miles it went again to Resta. De Palma got the lead for a short period at 145 miles, lost it to Resta and regained it again at 175 miles.

As De Palma worked up gradually from position to position in the flying field, he was shown to be a warm favorite with the crowd, who cheered constantly for him. Many of them remembered his hard luck three years ago when he had the race won and broke a connecting rod in the 197th lap. He had established a reputation as one of the best of drivers who suffered unaccountably from the worst of luck and the crowd wanted him to break his hoodoo.

When he swept over the line a winner in by far the fastest time that has ever been made on the track, only he and his mechanician knew that hard luck had again tried to overwhelm him in the same fatal 197th lap. He had once more broken a connecting rod, which had punched two holes in the bottom of the crank case. But he was able to keep on with three cylinders and only a slight slackening of pace.

The pit work, as the result of steady practise at changing tires during the practise spins before the race, was better than it had been in any previous contest. Many tire changes were made in about 30 seconds.

Six Cars Make Fast Time.

After the first four leaders had come home it was nearly half an hour before the second group of cars began to finish. These were O’Donnell’s Duesenberg, Burman’s Peugeot, Alley’s Duesenberg and Carlson’s Maxwell. O’Donnell made fifth place with a speed of 81.47 miles per hour, and Burman sixth, with 80.35 miles per hour. So that six cars of the 10 made better than 80 miles per hour.

Wilcox’s Stutz was seventh, Alley’s Duesenberg, eighth, Carlson’s Maxwell ninth and Van Raalte’s Sunbeam 10th. This car had much tire and hood trouble to delay it. The Emden was the only other car running and it was permitted to finish the race, making the distance at 70.75 miles per hour. The first four cars to finish came through without the lifting of the bonnet. But trouble of many varieties affected others, some of which finished and some of which had to be withdrawn from the race.

Babcock in his small Peugeot had made only one stop for tires and seemed to be going very well when suddenly he cracked a cylinder and found it necessary to with- draw. Burman had three slight mechanical troubles. After three hours running the cover of his gear case came loose, but it was tightened in 30 seconds during a stop for tires and supplies. At the end of four hours it was necessary to change some spark plugs and then later the copper pipe which takes the oil to the cam- shaft broke and had to be bound with rubber tubing. The Bugatti did not run well and was obviously under powered by the reduction made in piston throw to bring it into the race under the regulations as to dis- placement. Grant’s car had not enough. power to keep up with the terrific pace. set, and when repairs to the mud guard became necessary it was plainly of no use to continue.

Porporato in his Sunbeam at times hit a pace up to 90 miles an hour, but his car was unable to maintain it evenly as did the cars that finished first. When the race was three-fourths over a piston seized. This was probably due to the breaking of a piston ring. Before that happened, he had lost three minutes and 45 seconds stopping to fix the straps that held the bonnet of his car in place.

Von Raalte lost his hood altogether and was stopped by the officials, who insisted that he fetch it and put it on before he could continue: That caused the loss of a lot of time. He also had stops of 16 minutes and 19 minutes to fix the platform which carries the magneto on his car, losing, in all, nearly an hour at the pits.

The accident that caused Klein’s Kleinart to leave the track was a new one for the racing drivers. The partition between his gasoline and lubricating oil tanks gave way and the two mingled. This greatly overlubricated his engine and caused so much smoke that the officials were forced to rule the car off the track.

Cooper’s Sebring lost 42 minutes because of spark plug trouble and also incurred another stop to fix an accelerator pedal. Alley’s Duesenberg suffered no mechanical trouble except a loosened exhaust pipe. O’Donnell stopped his Duesenberg only three times and the only mechanical work done on the car was to replace a nut jarred from the brake bracket and a quick adjustment of one shock absorber. Mulford’s Duesenberg was put out of the race by a stripped gear, but he had previously stopped to adjust his steering gear and brake.

Failure of spark plugs in Rickenbacher’s Maxwell caused that car to withdraw. The plugs cracked soon after they were put in, apparently from excessive heat. Carlson’s Maxwell was the only car among those that finished which stopped only once. He suffered no mechanical trouble at all. Orr’s Maxwell broke a bearing in the rear axle and was forced to retire from the race. The Maxwells with two valves per cylinder had no plug trouble, while that with four valves ate up plugs as fast as they could be put in. This will probably be remedied by an improvement in cooling efficiency before the car again appears on the track.

The Emden proved to be a slow, but steady car, finishing in 11th place. It stopped only twice, once for four spark plugs and once for supplies.

John De Palma’s Hard Luck.

John De Palma in his Delage ran at a good pace until his flywheel loosened and he was forced to leave the track. This accident was probably due to injuries the car sustained in a smash-up in practise.

The Cino-Purcell stripped a timing gear in the 13th lap and was the first car to leave the race. The Mais was troubled with a flooding carburetor. On his second stop to fix it the driver overshot the pits and because he returned, leaving the track, he was disqualified.

The Bugatti, which proved to be very slow, broke a connecting rod on the back stretch and was out of the race. The little Cornelian showed remarkable speed for so small a motor and went out after three hours because a valve broke and fell inside the cylinder. It was troubled also by overheating and several stops had to be made for more water.

As the first four cars in the race came through absolutely without mechanical trouble, that is an indication that racing cars have been so far perfected that in the near future mechanical trouble of even a slight nature will be equivalent to defeat. The winning cars, stopping only for fuel, oil and tires, cut the time lost at the pits to the minimum.

This was the first race run at the track in which no one was injured. This was due in part to the exceptionally favorable conditions and also to the new retaining wall, which prevented the cars from skidding off the track onto the soft ground and tipping over, as has frequently happened in previous years, with sometimes very disastrous results.

The race was a triumph for wire wheels. All the cars entered were equipped with them. All also were equipped with Bosch ignition. Seventeen of the starters used the two-spark plug type and seven had single plugs. Every car in the race was fitted with the Motometer radiator indicator.

Winners Used Silvertowns.

Each of the 10 cars to place was equipped with Goodrich Silvertown Cord tires. There was more variety in the selection of carburetors. De Palma’s Mercedes was fitted with a Packard carburetor, Resta used a Zenith, the three Stutzes had Strombergs, the Master carburetor was used by Burman and the three Maxwells, and O’Donnell’s Duesenberg was equipped with a Schebler. For lubrication Oilzum was the most popular, practically all the cars using that oil. De Palma used Monogram and the three Sunbeams castor oil.

Overhead valves proved their efficiency by the fact that the first four cars to finish were equipped with them. In fact, 15 out of 24 starters used overhead valves.

The engines of the three Stutz cars were of this type and their performance for motors of entirely new design was entirely remarkable. The feat of Wilcox in running for hours with a broken valve spring and finishing in seventh place. speaks volumes for the efficiency of the new Stutz engine.

The striking performance of the Stutz is taken by technical experts as better proof than the chance winning of first place that American makers are able to design and build cars that will compare favorably with the best that the foreign makers can produce.

These new Stutz engines have nothing fundamentally new in design. They are the latest and most approved types worked out carefully with the best of material, and they show that American material and workmanship can equal any other.

In spite of the numerous handicaps under which the race. run from the commercial point of view, it proved to be an enormous success as a money maker. The results will enable the speedway company to pay handsome dividends on its stock for the year.

The attendance figures checked from actual count went fully 25,000 over the mark expected by the officials when it became necessary on Saturday to postpone the race until Monday.

The constant rains for the days preceding the race prevented many people who had planned a motor tour to Indianapolis from taking their trips and the dark, lowering clouds on the day of the race itself kept many more from the field who doubtless would have come. Yet 75,000 persons attended the race, paying $2 as an entrance fee and more for grandstand privileges.

Entrance Fee Was Doubled.

Last year the entrance fee was only $1, yet the doubling of the price had little effect on the crowd, which certainly would have reached 100,000 had the weather been different.

These figures show why it has suddenly become possible to interest capital in the erection of motor speedways at Sheepshead Bay, Chicago, Detroit and Cincinnati. They are a remarkable tribute to Carl G. Fisher, whose commercial imagination and good judgment have made him a great figure in the motor world.

There were few men in the motor car or any other business who believed the ex-bicycle racer when he proposed the Indianapolis speedway years ago and advanced the argument that its one day’s business a year would pay dividends on the investment.

But Fisher got the track built and the results have more than borne out his predictions. The owners of the track on the basis of this last result financially, are sure that they are on easy street for life.

Although other cities are now going into the speedway business, the Indianapolis course has a long tradition of great speed contests. Indianapolis is a small enough town so that a race is the big event of the year and the city at that time is the place of a great festival. The race is not lost there among a thousand other activities, as it may be in New York or Chicago. Furthermore, the fact that it will always be the first race of the year will maintain the interest in it.

Fisher the Big Leader.

Fisher is the head also of the company that is building the new track at Sheepshead Bay. It was his imagination and his ability to impart his enthusiasm to others that put the Lincoln highway on the map. He conceived the idea of the great national highway and interested in it the influential men who are carrying it to success. He also first suggested the Dixie highway through the South, which has just taken definite form.

American racing has become distinctly the greatest racing in the world. The prizes are so great that practically all the European racing teams may be expected to compete as soon as the war is over.

Foto captions.

Page 18 19. Palma’s Last Lap. – Resta in His Peugeot.

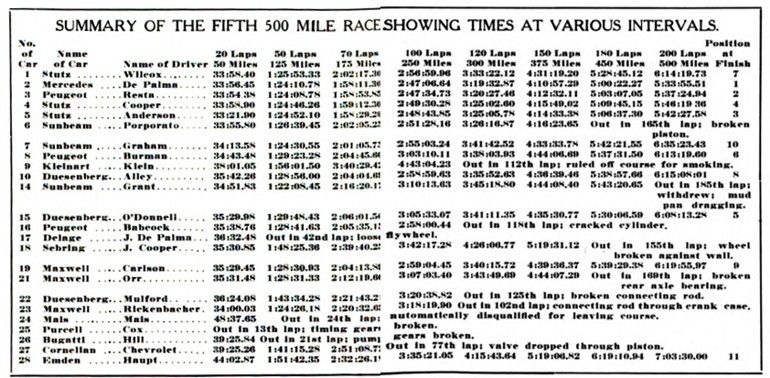

Table: SUMMARY OF THE FIFTH 500 MILE RACE SHOWING TIMES AT VARIOUS INTERVALS.

Out of race:

Sunbeam, Porporato; Out in 165th lap; broken piston.

Kleinart, Klein; Out in 112th lap; ruled off course for smoking.

Sunbeam, Grant; Out in 185th lap; withdrew; mud pan dragging.

Peugeot, Babcock; Out in 118th lap; cracked cylinder.

Delage, J. De Palma; Out in 42nd lap; loose flywheel.

Sebring, J. Cooper; Out in 155th lap; wheel broken against wall.

Maxwell, Orr; Out in 169th lap; broken rear axle bearing.

Duesenberg, Mulford; Out in 125th lap; broken connecting rod.

Maxwell, Rickenbacher; Out in 102nd lap; connecting rod through crank case.

Mais, Mais; Out in 24th lap; automatically disqualified for leaving course.

Purcell, Cox; Out in 13th lap; timing gears broken.

ugatti, Hill; Out in 21st lap; pump gears broken.

Cornelian, Chevrolet; Out in 77th lap; valve dropped through piston.

Page 20.

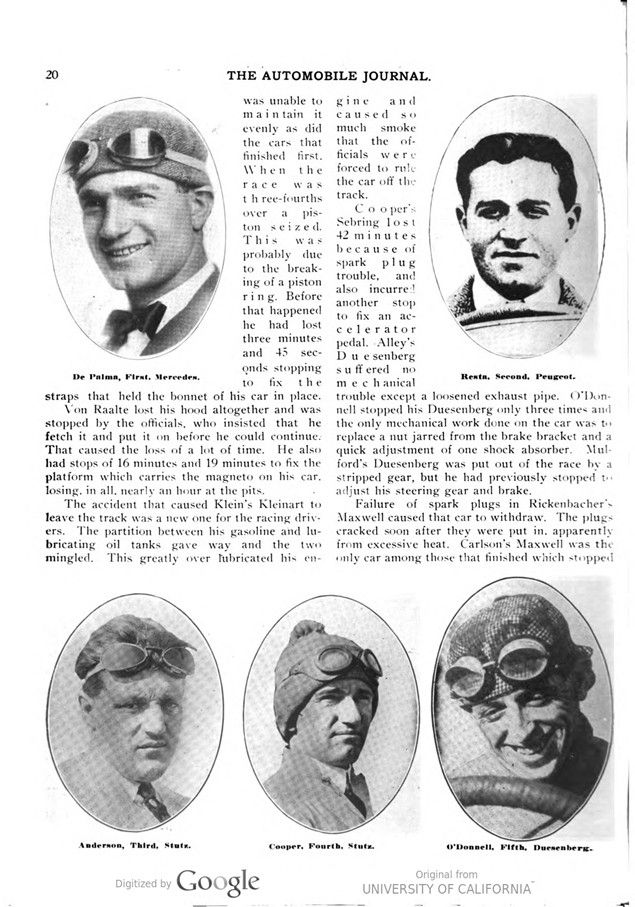

De Palma, First, Mercedes. – Resta, Second, Peugeot.

Anderson, Third, Stutz. – Cooper, Fourth, Stutz. – O’Donnell, Fifth, Duesenberg.

Page 21.

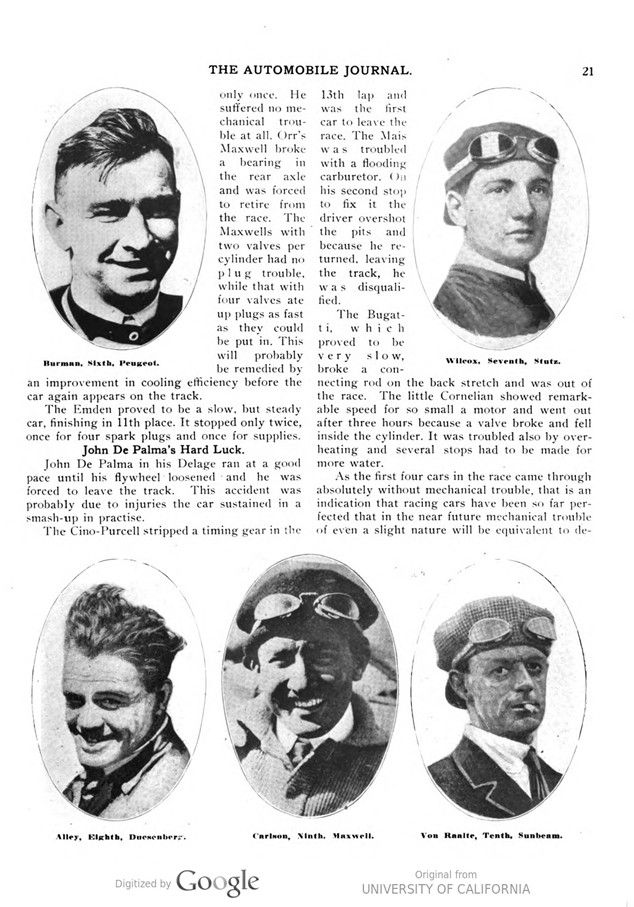

Burman, Sixth, Peugeot. – Wilcox, Seventh, Stutz

Alley, Eighth, Duesenberg. – Carlson, Ninth, Maxwell. – Von Raalte, Tenth, Sunbeam.

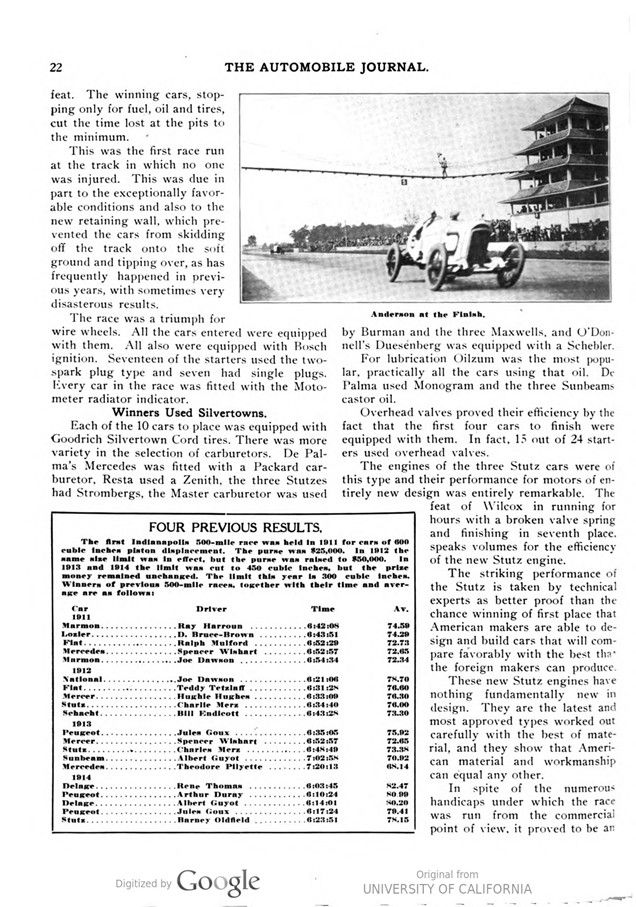

Page 22.

Anderson at the Finish. – Table:

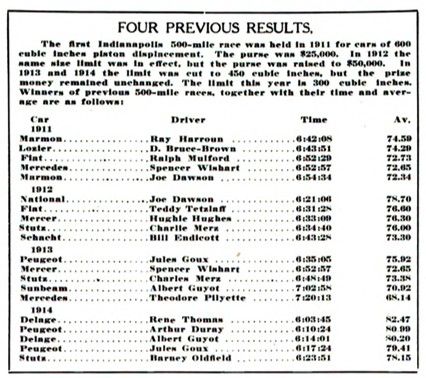

FOUR PREVIOUS RESULTS.

The first Indianapolis 500-mile race was held in 1911 for cars of 600 cubic inches piston displacement. The purse was $25,000. In 1912 the same size limit was in effect, but the purse was raised to $50,000. In 1913 and 1914 the limit was cut to 450 cubic inches, but the prize money remained unchanged. The limit this year is 300 cubic inches.

Winners of previous 500-mile races, together with their time and average are as follows: (see table).

Down below, some of the advertisements in the Automobile Journal of June 19, 1915.