Text and photos compiled by motorracingistory.com, with courtesy of hathitrust.org / Digital Library, USA.

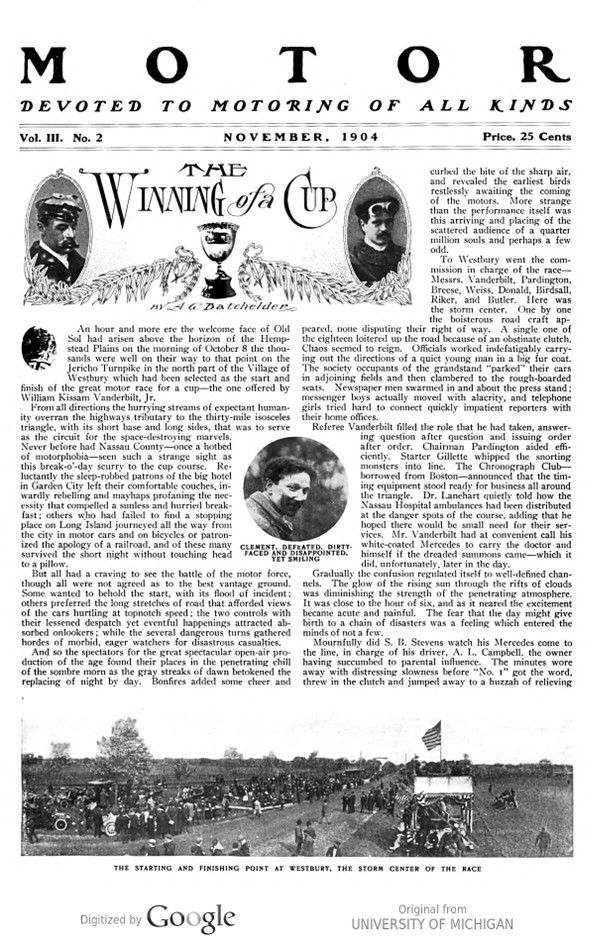

The Winning of a Cup – By A. G. Batchelder

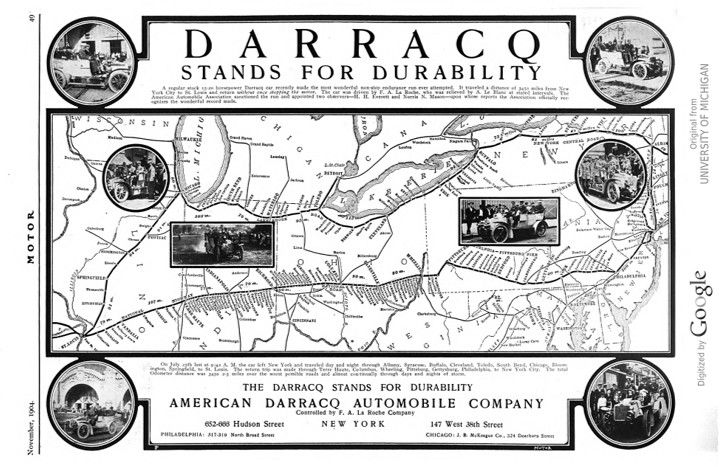

MOTOR – THE NATIONAL MAGAZINE OF MOTORING; DEVOTED TO MOTORING OF ALL KINDS

Vol. III. No. 2 NOVEMBER. 1904

An hour and more ere the welcome face of Old Sol had arisen above the horizon of the Hempstead Plains on the morning of October 8 the thousands were well on their way to that point on the Jericho Turnpike in the north part of the Village of Westbury which had been selected as the start and finish of the great motor race for a cup — the one offered by William Kissam Vanderbilt, Jr.

From all directions the hurrying streams of expectant humanity overran the highways tributary to the thirty-mile isosceles triangle, with its short base and long sides, that was to serve as the circuit for the space-destroying marvels. Never before had Nassau County — once a hotbed of motorphobia — seen such a strange sight as this break-o‘-day scurry to the cup course. Reluctantly the sleep-robbed patrons of the big hotel in Garden City left their comfortable couches, inwardly rebelling and mayhaps profaning the necessity that compelled a sunless and hurried breakfast; others who had failed to find a stopping place on Long Island journeyed all the way from the city in motor cars and on bicycles or patronized the apology of a railroad, and of these many survived the short night without touching head to a pillow.

But all had a craving to see the battle of the motor force, though all were not agreed as to the best vantage ground. Some wanted to behold the start, with its flood of incident; others preferred the long stretches of road that afforded views of the cars hurtling at topnotch speed; the two controls with their lessened despatch yet eventful happenings attracted absorbed onlookers; while the several dangerous turns gathered hordes of morbid, eager watchers for disastrous casualties.

And so the spectators for the great spectacular open-air production of the age found their places in the penetrating chill of the sombre morn as the gray streaks of dawn betokened the replacing of night by day. Bonfires added some cheer and curbed the bite of the sharp air and revealed the earliest birds restlessly awaiting the coming of the motors. Stranger than the performance itself was this arriving and placing of the scattered audience of a quarter million souls and perhaps a few odd.

To Westbury went the commission in charge of the race — Messrs. Vanderbilt, Pardington, Breese, Weiss, Donald, Birdsall, Riker, and Butler. Here was the storm center. One by one the boisterous road craft appeared, none disputing their right of way. A single one of the eighteen loitered up the road because of an obstinate clutch. Chaos seemed to reign. Officials worked indefatigably carrying out the directions of a quiet young man in a big fur coat. The society occupants of the grandstand „parked“ their cars in adjoining fields and then clambered to the rough-boarded seats. Newspaper men swarmed in and about the press stand; messenger boys actually moved with alacrity, and telephone girls tried hard to connect quickly impatient reporters with their home offices.

Referee Vanderbilt filled the role that he had taken, answering question after question and issuing order after order. Chairman Pardington aided efficiently. Starter Gillette whipped the snorting monsters into line. The Chronograph Club — borrowed from Boston — announced that the timing equipment stood ready for business all around the triangle. Dr. Lanehart quietly told how the Nassau Hospital ambulances had been distributed at the danger spots of the course, adding that he hoped there would be small need for their services. Mr. Vanderbilt had at convenient call his white-coated Mercedes to carry the doctor and himself if the dreaded summons came — which it did, unfortunately, later in the day.

Gradually the confusion regulated itself to well-defined channels. The glow of the rising sun through the rifts of clouds was diminishing the strength of the penetrating atmosphere. It was close to the hour of six, and as it neared the excitement became acute and painful. The fear that the day might give birth to a chain of disasters was a feeling which entered the minds of not a few.

Mournfully did S. B. Stevens watch his Mercedes come to the line, in charge of his driver, A. L. Campbell, the owner having succumbed to parental influence. The minutes wore away with distressing slowness before „No. 1“ got the word, threw in the clutch and jumped away to a huzzah of relieving cheers. Then followed the angel-faced Gabriel, hero of the frightful Paris-Madrid, favorite for the Vanderbilt trophy, and praised by everyone for his excessive modesty. He and his De Dietrich began the race calmly without much fuss or feather. Joe Tracy, another of the unassuming but confidence-aspiring type, received a tribute of applause as he put under power with his somewhat hastily improvised Royal Tourist stock car — an American entry.

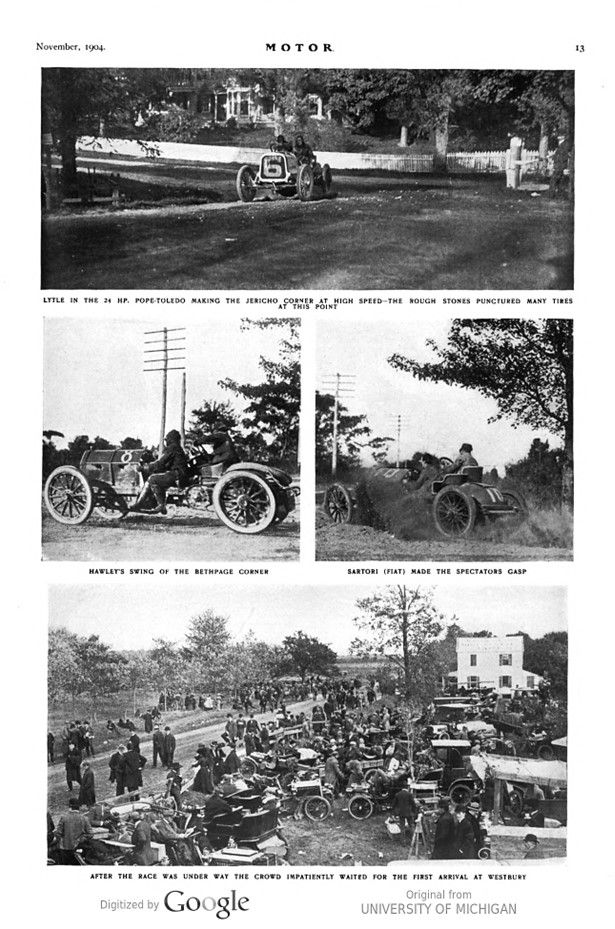

Webb and a Pope-Toledo came next; Arents, the unlucky, and his Mercedes started fifth; then Lytle and the second Pope-Toledo, destined to be a surprise of the day.

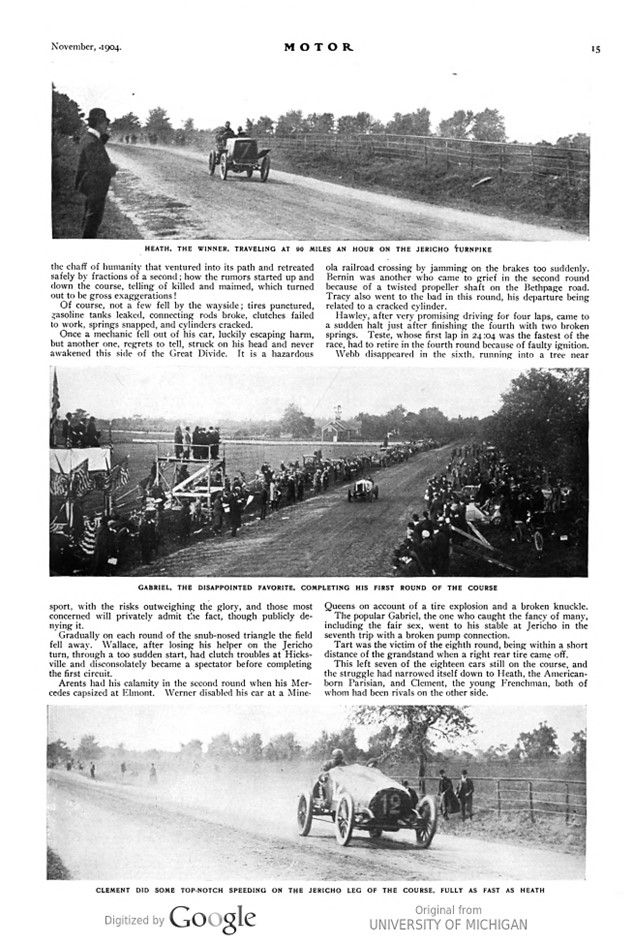

Heath, the Circuit des Ardennes winner, picked as the man to clip Gabriel’s wings, made a commanding figure as he prepared for the fray. His Panhard throbbed threateningly as it bounded down the oil-streaked road like a brute that had been held in leash beyond the limits of its forbearance.

Hawley piloted the raging Mercedes of E. R. Thomas to a good start, and when he came to grief later there were many sympathizers.

Werner did not obtain any approval for his setting out with the Mercedes of Clarence Gray Dinsmore, the obliging foreign representative of the Automobile Club of America; in fact, the experts rated it an inferior effort.

Sartori, who had drawn „No. 10,“ was the belated one with the Fiat of Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt. Not until after the race had been going for some time did Sartori get into the thick of it, and then in an unofficial manner that called for a stop at a control, though a revised decision permitted him to continue. Misfortune soon picked him again in the form of an obstinate clutch.

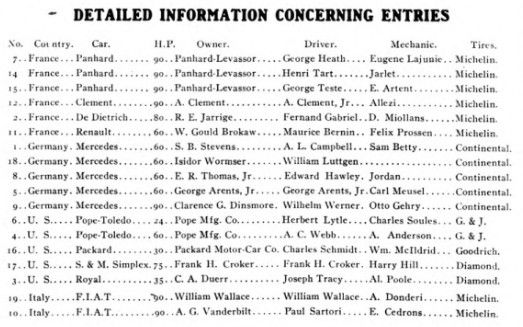

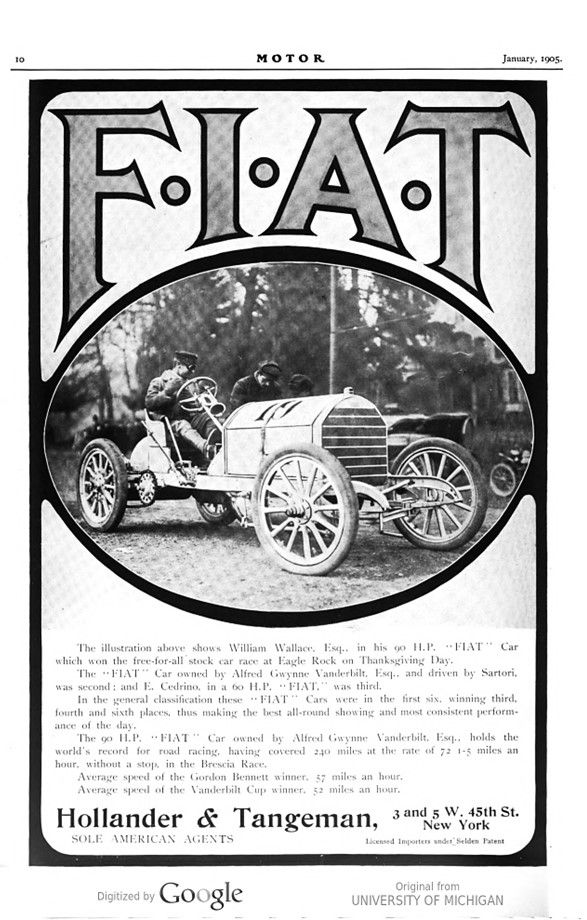

Bernin and the Renault of W. Gould Brokaw; Clement, the juvenile, and the powerful-looking Clement-Bayard; Tart, another Panhardite; Teste of the same camp; Schmidt, once the comrade of Fournier, with his beloved Packard Wolf; Frank Croker, son of the ex-Tammany „Boss,“ driving his new S. & M. Simplex; Luttgen and the Mercedes of Isidor Wormser; and finally William Wallace, the daring Bostonian, with his turbulent and powerful Fiat — that completed the list of participants, and none carried „No. 13.“

The fierce game of the motors was under way. For seven hours they were to chase one another around the triangle with its doubtful surface and its risky turns. It was a contention wherein the man counted as well as the mechanical monster which he guided. A steady arm and an unfailing eye were unavoidable requisites in this distance-devouring sport. The stakes being played for were not alone the possession of the cup of silver with its gold lining: the makers of two worlds were fighting for the American motor car trade, as Mr. Brisbane aptly described the prize that tempted the performers to endeavor that verged on the foolhardy. True there were several who reckoned only with glory and the cup, but the big premium traced to the industry and its invested millions.

But it must be told that the one catastrophe of the day had to do only with the cup. Young Arents, surcharged with the desire to prove his motor spurs, handled his car with a rash bravery that resulted in the death of his mechanic, Meusel, and nearly sent himself into the Great Beyond.

Every sport will have its victims, and motor competition will not be exempt. But even at its worst phase it deserves not the name of an amusement fit only for a „Roman holiday.“ One must employ caution driving a roused motor car, and novices had better know their lesson thoroughly before facing the starter. Arents, the impetuous, was a novice in racing, and the story subsequently told of how he excitedly left the Hempstead control with a tire before its shoe had been properly adjusted explains why disaster abruptly ended his driving for the day at Elmont. And so they chortled and spouted, and teufed clamorously, flying from the starting point the three miles to the Jericho turn in an inkling, taking this abrupt curve with scant hesitation, quickly reaching the Hicksville control, two miles away; easing down for a brief interval, and then diving out the Massapequa road for the risky Bethpage corner, three miles farther on; next six miles of straightaway earth skimming slackened in the Hempstead control with its momentary breathing spell: then five miles more to the apex of the roads at Queens, after making the swerve at Elmont where the Arents Mercedes came to grief; through Queens and a second turn into the Jericho turnpike, when the northern leg of the course offered a good stretch of going past the Waterbury stand.

How they chased one another, the speedier occasionally overtaking a slower and distressed competitor; how the foolish onlookers crowded into the road until the sharp- eyed watchers sighted a monster, which would come tearing along and in some miraculous manner scatter without harm the chaff of humanity that ventured into its path and retreated safely by fractions of a second; how the rumors started up and down the course, telling of killed and maimed, which turned out to be gross exaggerations!

Of course, not a few fell by the wayside; tires punctured, gasoline tanks leaked, connecting rods broke, clutches failed to work, springs snapped, and cylinders cracked.

Once a mechanic fell out of his car, luckily escaping harm, but another one, regrets to tell, struck on his head and never awakened this side of the Great Divide. It is a hazardous sport, with the risks outweighing the glory, and those most concerned will privately admit the fact, though publicly denying it.

Gradually on each round of the snub-nosed triangle the field fell away. Wallace, after losing his helper on the Jericho turn, through a too sudden start, had clutch troubles at Hicksville and disconsolately became a spectator before completing the first circuit.

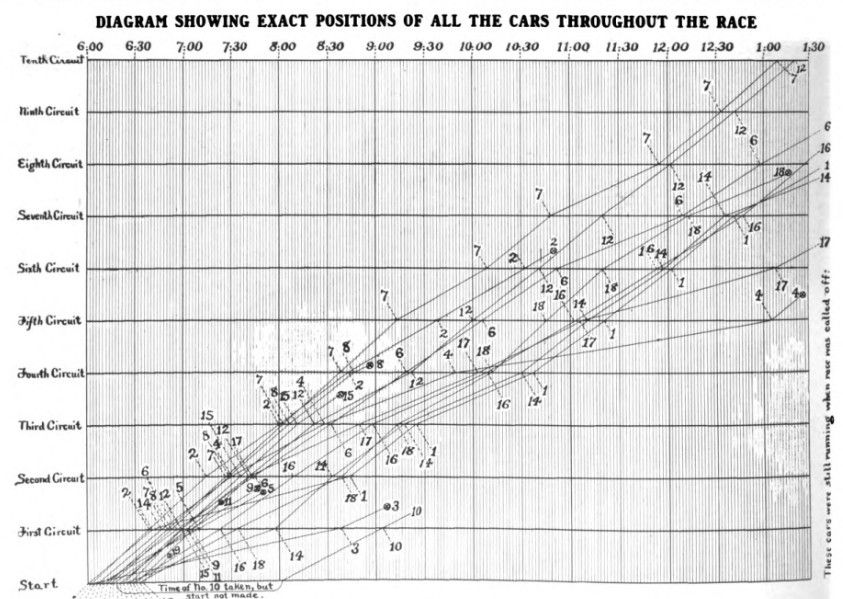

Arents had his calamity in the second round when his Mercedes capsized at Elmont. Werner disabled his car at a Mineola railroad crossing by jamming on the brakes too suddenly. Bernin was another who came to grief in the second round because of a twisted propeller shaft on the Bethpage Road. Tracy also went to the bad in this round, his departure being related to a cracked cylinder.

Hawley, after very promising driving for four laps, came to a sudden halt just after finishing the fourth with two broken springs. Teste, whose first lap in 24:04 was the fastest of the race, had to retire in the fourth round because of faulty ignition. Webb disappeared in the sixth, running into a tree near Queens on account of a tire explosion and a broken knuckle.

The popular Gabriel, the one who caught the fancy of many, including the fair sex, went to his stable at Jericho in the seventh trip with a broken pump connection.

Tart was the victim of the eighth round, being within a short distance of the grandstand when a right rear tire came off.

This left seven of the eighteen cars still on the course, and the struggle had narrowed itself down to Heath, the American-born Parisian, and Clement, the young Frenchman, both of whom had been rivals on the other side.

Teste, undoubtedly a capable driver, had been the leader for three laps, and then it was that Heath forged to the front in the fourth circuit, where he remained until the eighth round, when tire punctures compelled him to give way to Clement, who had lost some time in the fourth lap through a leaky gasoline tank. Thirty minutes of tire repairing for Heath in this eighth round enabled Clement to obtain a lead of 3 min. 8 sec. Once more in the running, Heath reduced the margin of his rival to 1 min. 48 sec. in the ninth circuit.

Then the excited throng awaited the final lap and speculated during the waiting.

„Car coming! car coming!“ shouted the clarion voiced Prunty, and Heath came leaping up the road and did a whirlwind finish to the music of a volley of cheers.

If Clement arrived inside of ten minutes the victory would belong to him, for he started that much behind Heath at the beginning of the race. Fearfully the Heath adherents strained their eyes, momentarily expecting the blue-colored racer to emerge. But the minutes ticked out their existence and Clement came not. Gleeful were the shouts of „Heath wins! Heath wins!“ that went up at the expiration of the ten minutes.

And just then Clement hove in sight. It was by an advantage of 1 min. 28 sec. that Heath took the cup.

Apprised of this fact, the people cared for no more racing, and oblivious of the fact that five cars were still encircling the course they flooded the road in all directions, intent upon their home-going. A hint to Referee Vanderbilt from a newspaper man, and an edict went forth immediately notifying the remaining contestants to discontinue. Of these Lytle, who won the first motor road race ever held in England — November 14, 1896, from London to Brighton — had just completed his ninth lap, after having done the most consistent traveling of the day with a 24-horsepower Pope-Toledo, plainly at a disadvantage because of his lesser power. Schmidt and the Packard Wolf were another handicapped pair that had been performing admirably with only 30-horsepower and had fourth place mortgaged. Campbell and the Stevens Mercedes bad fifth place in hand. Frank H. Croker, with his S. & M. Simplex, had all sorts of tire troubles, but was up and doing on his seventh round when the signal came to stop. Luttgen with the Wormser Mercedes had just completed his eighth round when the motor battle ended. These five were loath to quit.

If one is beaten soundly, he is inclined to accept it with equanimity. But Clement thought that an injustice had been done to him at the Hicksville control, and with the close call of 1 min. 28 sec. vividly before him, he filed a vociferous wordy protest, later set forth in writing, which Referee Vanderbilt and his fellow-members of the commission for the 1904 race passed upon adversely in a long-drawn-out session at the Garden City Hotel in the evening. Clement charged that he had been delayed three minutes at Hicksville, the officials not interpreting the rules as he understood them in regard to making repairs while in the control. The charge of these three minutes against him in his net time was what threw the young Frenchman into a state of mind and resulted in his protest at the finish. Since it was shown at the hearing that Heath did not do anything of the kind, even though it was alleged that other contestants had been guilty, nothing remained for the commission except to leave the laurels of victory with Heath, and Clement accepted the situation like a good sportsman.

Concerning Heath, one inclines to the belief that his popularity will never be very extensive. In fact, a tale that found its way into gossip several days after the race contained apparently truthful statements that Heath had been purposely misinformed by supposed friends that he was many minutes ahead of his nearest rival, when as a matter of fan his advantage was exceedingly meagre. Awakened to the falsity of the information, Heath drove like a madman in the closing two rounds. It was said that the misinformation came from a coterie, the members of which desired to see a Frenchman win rather than the Panhard car driven by an American.

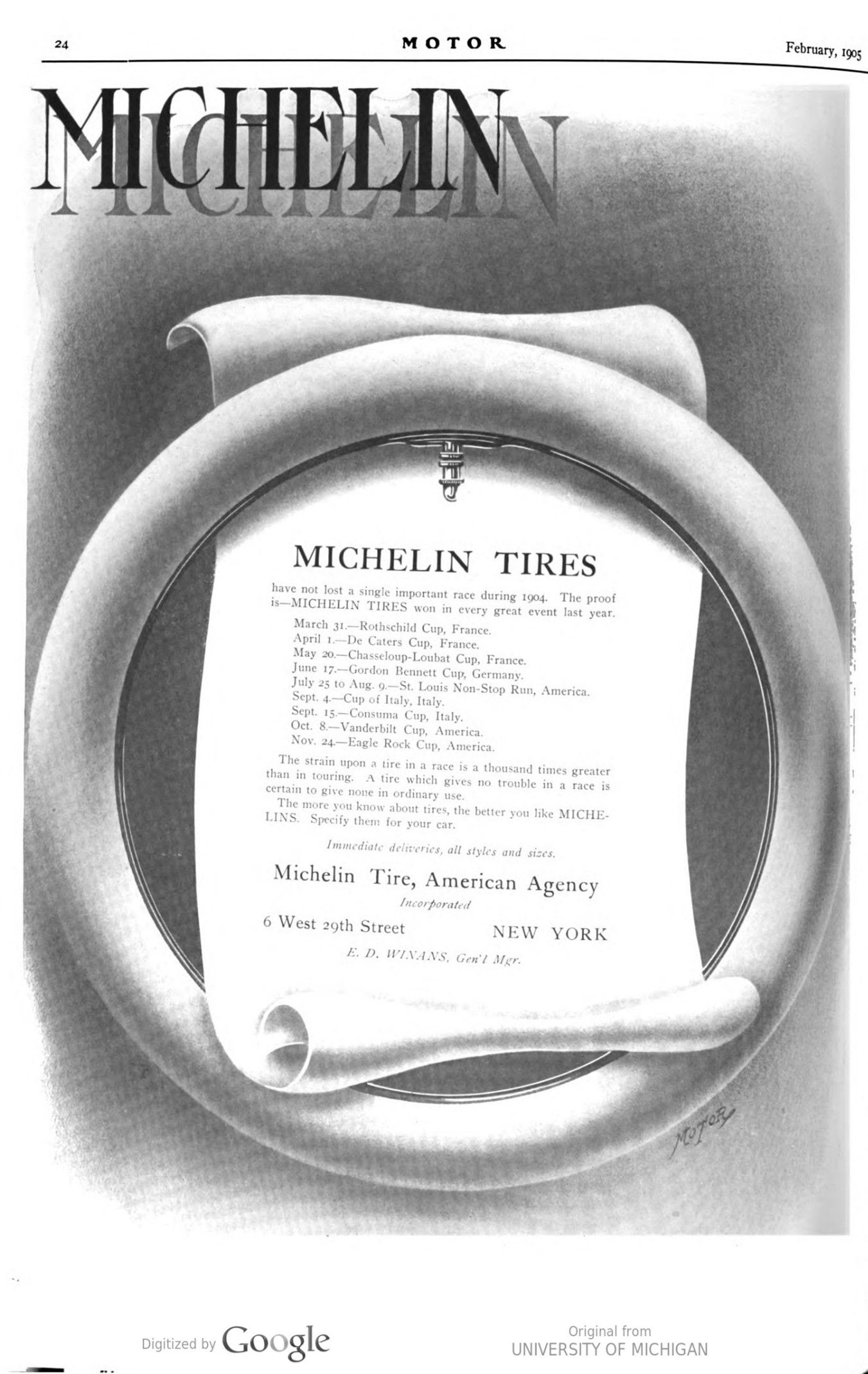

The tire companies took a great interest in the race, and as a result Heath received $1,000 and Clement $500 from the Michelin Co. Possibly there were a few nails distributed on the course by malicious people, though several machines suffered severely on the Jericho turn after the soft coating of the road had been forced back and the rough stones uncovered.

Is the race worth the time and expense and trouble and danger is a question that will be variously answered. Apparently, Nassau County itself desires the event, and if local option holds good in motor racing, as in many other things, that same county will seek the event next year.

Looked at from the standpoint of a maker, I would simply quote one whose company thus far has had naught to do with racing, E. R Thomas, of Buffalo: „That one race did more for motoring than half a year’s racing under ordinary circumstances. America will see more of these races, and it will be a splendid thing for motoring in genera! everywhere.“

Plainly unprepared for the contention with the finished racing product of the leading European makers, the American manufacturers, nevertheless, entered the contest rather than that the trade of this country should not be represented, knowing full well that the advantage rested with their foreign commercial rivals. And it was a very creditable showing that they made, three of the five American cars that started being numbered among the finishers. Of Germany’s five, only two survived the day; of the six French machines, two weathered the struggle, running first and second: and only one of the two Italian cars reallv started and that one met with bad luck. All credit to the Pope-Toledo, the Packard, the S. & M. Simplex, with the Royal not forgotten for its plucky effort. Another year — well, another year will tell its own story, assert the American racing enthusiasts.

Of the Long Island participants, one writer sums up their part in the perilous game in this manner: „All went into the race fully cognizant of its danger, and of their own free will; that they played with Death, and if Death won, it lay between them and him. This sounds harsh; but it is true.“

Continuing, this same writer, Porter Emerson Brown, refers to a situation which might be prevented another year, possibly by the employment of citizen soldiery. Mr. Brown asks:

„Why the casualties of the day were not counted by the score instead of by the unit is something that passeth all understanding, at least all of mine. At the time of the Paris-Madrid race, the world spoke scornfully of the lack of intelligence of the French peasant. According to my notion the only difference between the spectators of the Paris-Madrid race and those of the Long Island is that the latter were more fortunate in not having an accident to a machine at a crowded place and possibly were a bit quicker on a sidestep.“

There will be plenty of time before the next race to learn whether it is desired, and whether the use of the highway for one day constitutes a violation of the law.

Photo Captions.

Page 11:

CLEMENT, DEFEATED, DIRTY FACED AND DISAPPOINTED, YET SMILING.

THE STARTING AND FINISHING POINT AT WESTBURY, THE STORM CENTER OF THE RACE.

Page 12:

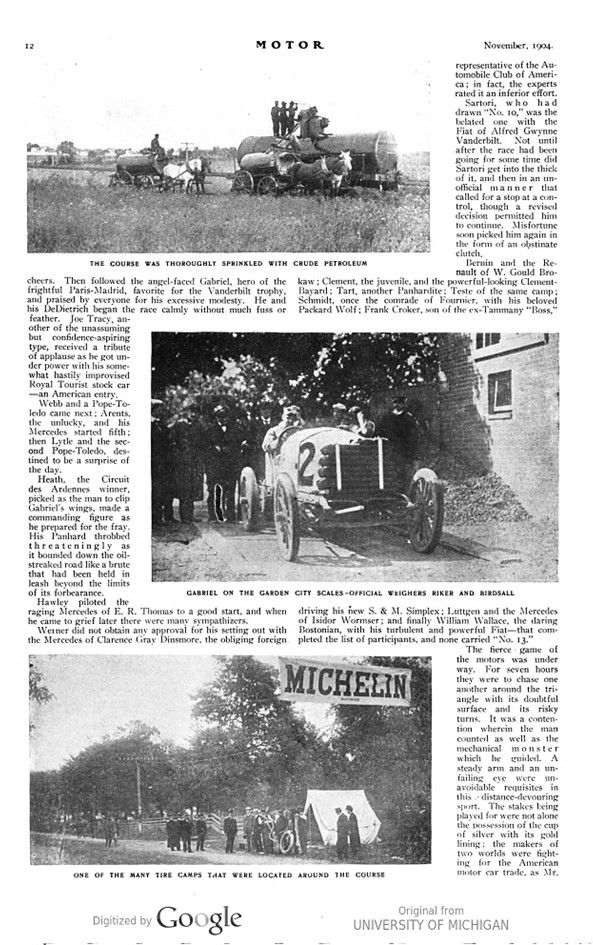

THE COURSE WAS THOROUGHLY SPRINKLED WITH CRUDE PETROLEUM.

GABRIEL ON THE GARDEN CITY SCALES – OFFICIAL WEIGHERS RIKER AND BIRDSALL.

ONE OF THE MANY TIRE CAMPS THAT WERE LOCATED AROUND THE COURSE (MICHELIN).

Page 14:

THE ACTIVITY CAUSED BY A CAR ENTERING THE HEMPSTEAD CONTROL – LYTLE IN THE POPE-TOLEDO.

REPLENISHING THE GASOLINE – WATER COOLING FOR TIRES.

AT THE EXIT OF THE HEMPSTEAD CONTROL, WHERE THERE WAS MUCH DOING ALL THE DAY (SIX MINUTE CONTROL).

Page 15:

HEATH, THE WINNER, TRAVELING AT 90 MILES AN HOUR ON THE JERICHO TURNPIKE.

GABRIEL, THE DISAPPOINTED FAVORITE, COMPLETING HIS FIRST ROUND OF THE COURSE.

CLEMENT DID SOME TOP-NOTCH SPEEDING ON THE JERICHO LEG OF THE COURSE, FULLY AS FAST AS HEATH.

Page 16:

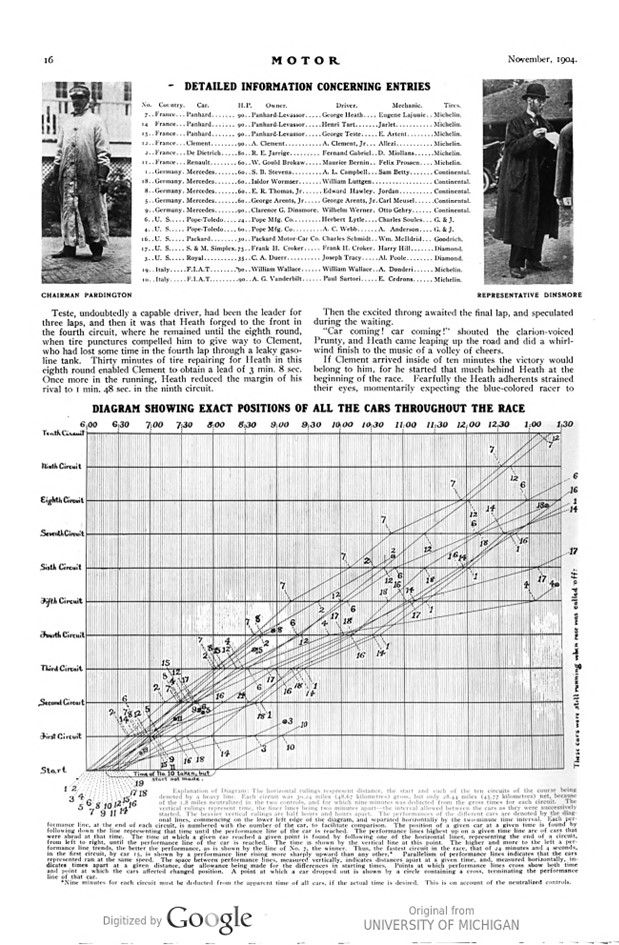

CHAIRMAN PARDINGTON – REPRESENTATIVE DINSMORE.

Page 16.

DIAGRAM SHOWING EXACT POSITIONS OF ALL THE CARS THROUGHOUT THE RACE.

Explanation of Diagram: The horizontal rulings represent distance, the start and each of the ten circuits of the course being denoted by a heavy line. Each circuit was 30.24 miles (48.67 kilometres) gross, but only 28.44 miles (45.77 kilometres) net, because of the 1.8 miles neutralized in the two controls, and for which nine minutes was deducted from the gross times for each circuit. The vertical rulings represent time, the finer lines being two minutes apart—-the interval allowed between the cars as they were successively started. The heavier vertical rulings are half hours and hours apart. The performances of the different cars arc denoted by the diagonal lines, commencing on the lower left edge of the diagram, and separated horizontally by the two-minute time interval. Each performance line, at the end of each circuit, is numbered with the number of the car, to facilitate comparison. The position of a given car at a given time is found by following down the line representing that time until the performance line of the car is reached. The performance lines highest up on a given timeline are of cars that were ahead at that time. The time at which a given car reached a given point is found by following one of the horizontal lines, representing the end of a circuit, from left to right, until the performance line of the car is reached. The time is shown by the vertical line at this point. The higher and more to the left a performance line trends, the better the performance, as is shown by the line of No. 7, the winner. Thus, the fastest circuit in the race, that of 24 minutes and 4 seconds, in the first circuit, by car 15, is shown by a performance line rising more sharply upward than any other. * Parallelism of performance lines indicates that the cars represented ran at the same speed. The space between performance lines, measured vertically, indicates distances apart at a given time, and measured horizontally, indicates times apart at a given distance, due allowance being made for the differences in starting times. Points at which performance lines cross show both time and point at which the cars affected changed position. A point at which a car dropped out is shown by a circle containing a cross, terminating the performance line of that car. * Nine minutes for each circuit must be deducted from the apparent time of all cars if the actual time is desired. This is on account of the neutralized controls.

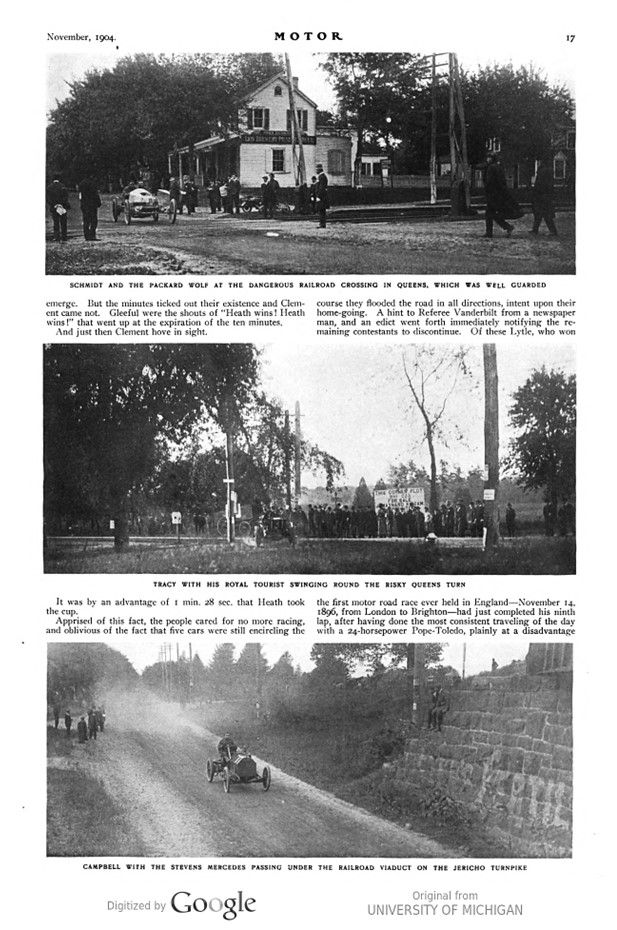

Page 17:

SCHMIDT AND THE PACKARD WOLF AT THE DANGEROUS RAILROAD CROSSING IN QUEENS, WHICH WAS WELL GUARDED.

TRACY WITH HIS ROYAL TOURIST SWINGING ROUND THE RISKY QUEENS TURN.

CAMPBELL WITH THE STEVENS MERCEDES PASSING UNDER THE RAILROAD VIADUCT ON THE JERICHO TURNPIKE.

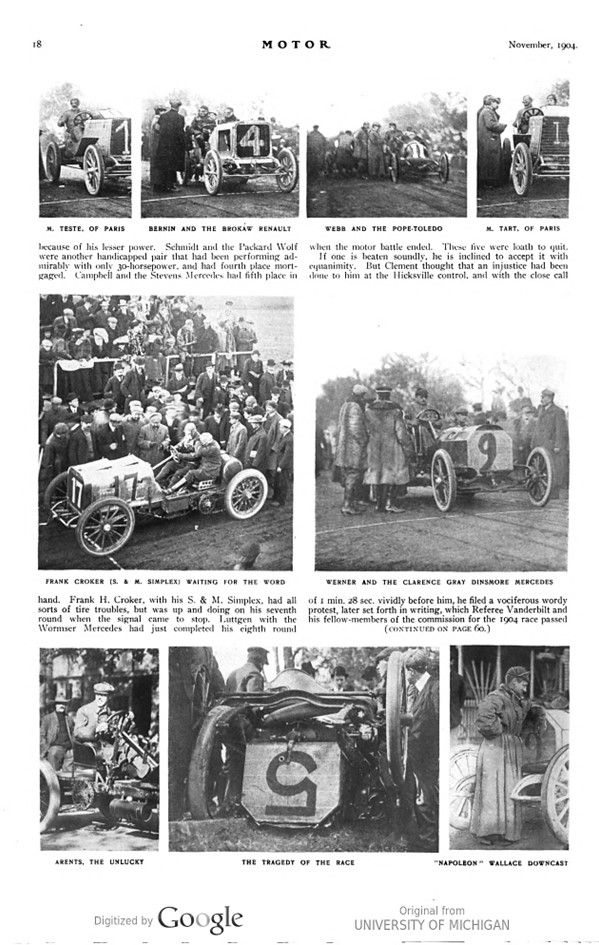

Page 18:

M. TESTE. OF PARIS – BERNIN AND THE BROKAW RENAULT

WEBB AND THE POPE-TOLEDO – M. TART, OF PARIS.

FRANK CROKER (S. & M. SIMPLEX) WAITING FOR THE WORD

WERNER AND THE CLARENCE GRAY DINSMORE MERCEDES.

ARENTS, THE UNLUCKY – THE TRAGEDY OF THE RACE – „NAPOLEON“ WALLACE DOWNCAST.

HAWLEY TELLING MR. THOMAS HOW IT HAPPENED.