Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Motor Age, Vol. XXXIX, No. 21, May 26, 1921, page 10 – 15

Harking Back a Decade

By ROY E. BERG

What Ten Years of Racing on the Hoosier Oval Recall

battling by science against the forces of nature. Man has evolved cunning machines capable of sustained high speeds, machines that travel farther at these high speeds than the most highly perfected locomotives. During the years from 1911 to now, the Indianapolis track has become a factor in the lives of racing men. To have won a race on this track places the name of the winner in the archives of the racing world.

No man has yet won the Memorial Day event twice; there have been eight races, this year being the ninth in ten years of racing on the track, and there have been eight different winners. Many of the racing stars of old are still pushing their fire spitting chariots around the track and in one or two instances drivers who started in the first race ever held on the track are still plying their trade and furthermore some of these drivers have entered and driven in every race held since the first.

A LABORATORY OF SCIENCE

The Indianapolis track has become of international importance to the automotive world. Every country of any importance in automotive manufacturing has at one time or another been represented by speed cars. Drivers from the world over have been at the track to pilot the cars.

Science in all its cunning has contrived to array all its forces against the Indianapolis track. The laboratory of the metallurgist has produced steels and light weight alloys capable of withstanding terrific strains from the impact of the road. High speed engines have been designed by the engineer and the power developed by these engines is remarkable for the size of the engine. All this development has not been done overnight, however.

Gradually through the slow process of evolution these engines and designs have been created, and each design has been based on the success and experience of the preceding. Strict comparison of these race cars from year to year reveals little difference but when compared over a decade it is easy to see why the cars are doing what was expected of them.

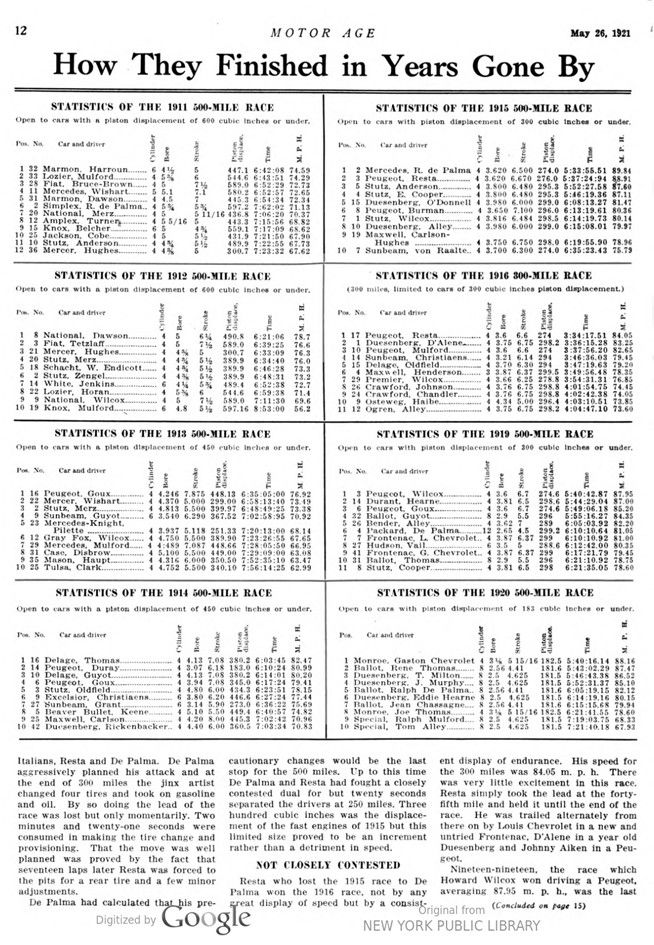

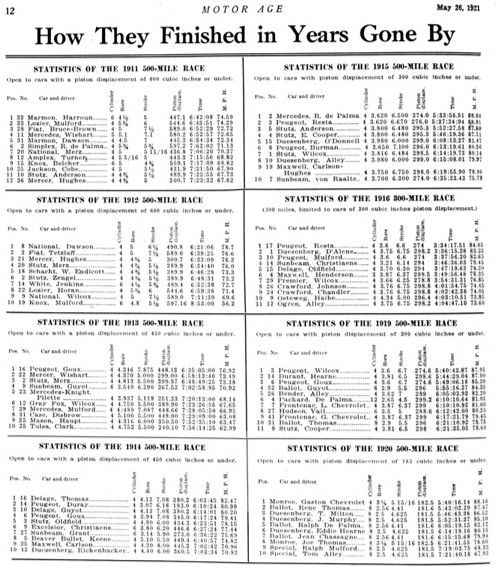

Reviewing the events of the races since 1911 we find many thrilling incidents. The uncertain is always happening in these big races, and in the first race, after 400 miles had been covered, the lead position was still in the balance, hanging to either of four contending Harroun, Mulford, Bruce-Brown, Wishart, and De Palma. Harroun was driving a big yellow Marmon having a bore and stroke of 4½ by 5 inches with six cylinders.

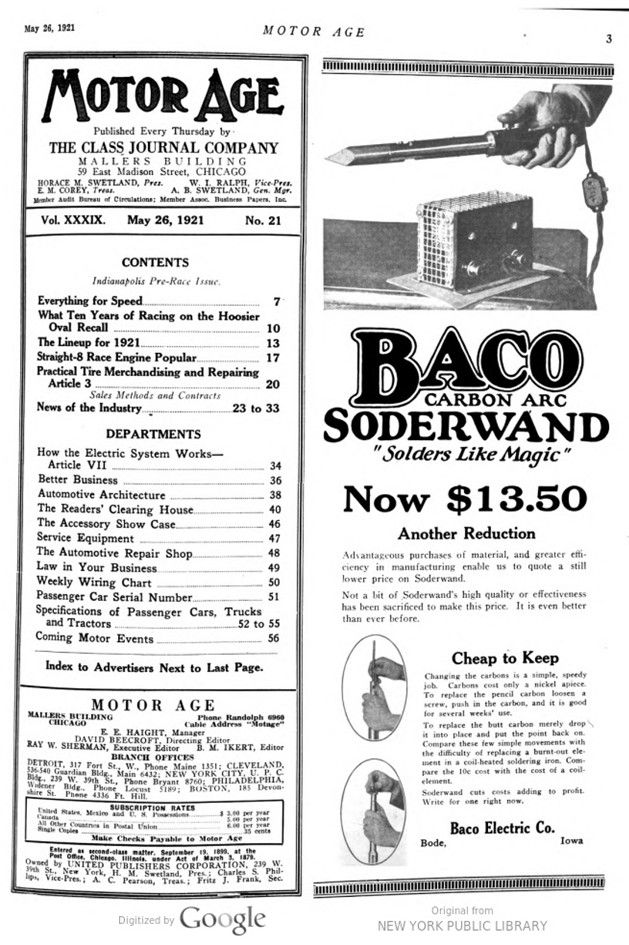

The wheelbase of the car was 116 inches, which is quite different from that on the winning car last year, 96 inches. Harroun’s lead after 450 miles was by a small margin. A tire change would have put him in second or third position. In the very few remaining laps of the race these four contenders holding the first four places were positioned in the same lap. The average speed of the winner was 74.7 m. p. h. It will be noted that the piston displacement of these cars was 476 cubic inches.

LOSES ON LAST LAP

The second race, held in 1912, was won by Dawson driving a National covering the 500 miles at an average speed of 78.7 m.p.h. The National had a four-cylinder engine with a bore and stroke of 5 by 614 and a piston displacement of 490.8 cubic inches. This is the race that De Palma was voted the hard luck crown by universal acclamation. De Palma had the race cinched at 495 miles. With two and one-half laps to go one of the pistons of De Palma’s Mercedes broke and victory was snatched from the Italian driver.

Ninety thousand people saw De Palma push his car in for the last lap. During 495 miles of travel De Palma had held first place and had broken all track records. Teddy Tetzlaff, driving a Fiat, drove in for second place at an average of 76.6 m. p. h. Hughes, in a Mercer, finished third at an average of 76.3 m. p. h. and Merz, in a Stutz, finished fourth averaging 76 m. p. h.

The victory in the third race fell to M. Jules Goux who spurred his car on to faster and faster speed through the use of high-grade gasoline, castor oil and champagne. It is said that Goux consumed seven pints of champagne during the race and it was to this stimulant that Goux attributed his victory. From the 330-mile lap on, Goux assumed the lead and held it to the finish. The speed of the winner was 75. m. p. h., and the car was a Peugeot. Second position went to Wishart, driving a Mercer, averaging 73.92 m. p. h. Wishart had fought a steady battle all through the race. His position in the early part was very low and he was never regarded as a contender until after 300 miles of travel. His pace steadily increased, and only twice during the whole race did he relinquish any gain he had made. These losses were minor and were caused by stoppage for gasoline and tires. (Had Wishart been able to start off at a better rate and maintain his same relative position that he assumed in reality, he would have won. But this is one of those „ifs“ and „would have beens“ and is, therefore, another story.)

Up to this time the American built cars had been the winners on the track but in the race of 1913, the car driven under the Tricolor of France carried away the laurels.

The next year, 1914, saw another French car win the race, this one being a Delage driven by the old veteran Rene Thomas. Also, much to the humility of the American built cars the foreign makes captured second, third, fourth, sixth and seventh places; seventh place being won by the Sunbeam driven by an American. This year saw the track record of 78.7 m.p.h., made by Dawson in the National in 1912, broken. The methodical Thomas driving a very conservative race brought in the bacon at 82.47 m. p. h.

PREDICTS WINNING SPEED

Before the race started Thomas said, in his quiet manner, that he would average 83 m. p. h. His victory was six laps ahead of second place made by Duray in his Peugeot at 80.99 m. p. h. Albert Guyot in a Delage made third place at 80.2 m. p. h. and Goux, winner of the previous race, came in fourth averaging 79.41 m. p. h. Luck seemed to be favoring everyone on the day of this race.

Charles Sedwick, who directed the race, rolled out of his hammock early Monday morning and, upon walking over the track, picked up a horseshoe and there upon declared that the track record would be broken, and it was. Up to this time there had been no limitations placed on piston displacement of the cars and 1915 saw the introduction of a ruling limiting displacement to 300 cu. in. The smaller cars of 1915 were not only faster but seemed to perform with much greater regularity. Ralph De Palma who, up to this time, had been a serious contender in all races and who, three years before, had been a hero in defeat, won the race. Again, the track record was shattered. Driving the 500 miles at an average speed of 89.84 m. p. h. it is interesting to note, in this connection, that Ralph De Palma’s track record still stands.

In this race De Palma almost outran his jinx. In the race of 1912 when Ralph covered 495 miles it will be recalled that the Italian’s mount balked by blowing in a piston head. The race, of 1915 which he won at the record-breaking speed almost duplicated the heartbreaking defeat formerly experienced by this favorite of the track. De Palma had five miles to go when a connecting rod broke and punched a hole in the crank case.

The remaining miles were covered on three cylinders and as the checkered flag was waved over his head the last drop of oil poured out from the crank case. The next three drivers, Resta in a Peugeot, averaging 88.91 m. p. h., Anderson in a Stutz, averaging 87.60 m. p. h., and Earl Cooper in a Stutz, averaging 87.11 m. p. h. broke the track record of the previous year. It was this race that witnessed the fighting of the battle between the two Italians, Resta and De Palma. De Palma aggressively planned his attack and at the end of 300 miles the jinx artist changed four tires and took on gasoline and oil. By so doing the lead of the race was lost but only momentarily. Two minutes and twenty-one seconds were consumed in making the tire change and provisioning. That the move was well planned was proved by the fact that seventeen laps later Resta was forced to the pits for a rear tire and a few minor adjustments.

De Palma had calculated that his precautionary changes would be the last stop for the 500 miles. Up to this time De Palma and Resta had fought a closely contested dual for but twenty seconds separated the drivers at 250 miles. Three hundred cubic inches was the displacement of the fast engines of 1915 but this limited size proved to be an increment rather than a detriment in speed.

NOT CLOSELY CONTESTED

Resta who lost the 1915 race to De Palma, won the 1916 race, not by any great display of speed but by a consistent display of endurance. His speed for the 300-miles was 84.05 m. p. h. There was very little excitement in this race. Resta simply took the lead at the forty-fifth mile and held it until the end of the He was trailed alternately from there on by Louis Chevrolet in a new and untried Frontenac, D’Alene in a year old Duesenberg and Johnny Aiken in a Peugeot. race.

Nineteen-nineteen, the race which Howard Wilcox won driving a Peugeot, averaging 87.95 m. p. h., was the last race for 300 cu. in. cars. It was decided, after this race was over, that 300 cu. in. cars had been developed to the highest point of efficiency and that if any great strides were to be made in automotive engineering, they would have to come through reducing the size of the engine and by clever designing, to increase their efficiency. Eddie Hearn won second place driving a Durant Special and the veteran, Jules Goux, rolled in for third.

De Palma, in this race, led the field for the first 150 miles at the end of which time his average was better than 92 m. p. h. After a short stop for minor adjustments during which time Louis Chevrolet took first place, the Italian came back and hopped the pace up to 91.6 m. p. h. from 90 m. p. h. which Chevrolet had been maintaining. De Palma today holds the 100-mile record as well as the track record.

MANY DEATHS IN WAKE

A number of men were killed during this race, and it is said that this was the bloodiest affair ever held on the famous oval. The Roamer car, driven by Le Cocq, entering the backstretch on its ninety-sixth lap blew a tire, skidded and the tail piece of the car scraped along the inner wall. The gas tank was torn open, the car swerved from its course and overturned, gasoline spreading over the hot exhaust pipe, igniting, and the driver, with his mechanician, was killed instantly.

Arthur Thurman, said to be a lawyer from Washington, D. C., driving his own car, had an accident after having traveled 110 miles. The car overturned and in the resulting crash against the wall, Thurman was killed. The fourth man to be killed died as a result of a break in the timing wire occasioned by Louis Chevrolet’s car driving across the wire with a broken rear wheel, the brake drum of which severed the wire. Shannon immediately following Chevrolet was caught in the snarls of the spring steel wire, as he passed by, the wire’s end cutting him near the jugular vein. There were 106 pit stops in this race, which fact is interesting to compare with the record of the succeeding race.

In following the course of events on the Indianapolis track we have seen that the first two races were won by American built cars. Up to and including 1919, since the first two races were held, not an American car had come in first, but in 1920, the European precedent was shattered by the victory of Gaston Chevrolet driving a Monroe car.

This year also saw the entry of the small car having a displacement of 183 cu. in. The average speed of the winner was 88.16 m. p. h., which was faster than the preceding year when cars of almost twice the displacement were run. René Thomas who won the fourth race held on the track secured second place in his Ballot and Tommy Milton drove in for third place averaging 86.52 m.p.h. It was this race that proved conclusively the ability of the small engine to attain great speeds.

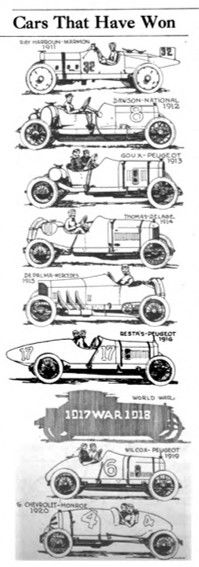

Cars That Have Won

RAY HARROUN – MARMON 1911 #32

DAWSON – NATIONAL 1912 #8

GOUX – PEUGEOT 1913

THOMAS – DELAGE 1914 #11

DE PALMA – MERCEDES 1915

RESTA’S – PEUGEOT 1916 #17

1917 WORLD WAR 1918

WILCOX – PEUGEOT 1919 #6

G. CHEVROLET – MONROE 1920 #4