The winner Jules Goux drank sparkling wine as a refreshment, many times during the race. This on itself lead to much astonishment by many Americans…… prohibition was on the lure. And not too less, mind you! „Six pints of bubbling, invigorating champagne“ as was written. This article is a vivid description of the most saillaint issues of the race and it deals not only with wine, but also with lubricating oil and the ongoing fight between the several contestants.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

MOTOR AGE Vol. XXIII, No. 23 Chicago, June 5, 1913

Champagne, Castor Oil and Gasoline

The Liquid Ingredients in M. Jules Goux‘ Victory

By J. C. Burton

“Sans le bon vin, je ne serais pas été en état de faire la victoire.“

SIX pints of sparkling wine won for Jules Goux, of Paris, the third annual international sweepstakes at the Indianapolis motor speedway last Friday.

Six pints of bubbling, invigorating champagne cost America the coveted laurels with which Ray Harroun and Joe Dawson were crowned in 1911 and 1912, respectively. Six pints of non-Bryanized grape juice restored to France the speed supremacy of the new world, a supremacy made possible by the triumphant feats of George Heath, Victor Hemery and Louis Wagner in the early days of Vanderbilt cup competition.

Worshipping the Great Joss, Speed

Six and a half hours after the bomb which sent a roaring monsoon of muscle and steel away to sweep time and space before it in a 500-mile rampage exploded, the grease-spattered hood of the blue Peugeot was flicked by the checkered flag of victory and two kisses were imprinted on the dirty cheek of Monsieur Goux.

One hundred thousand worshippers in the temple of the great joss Speed paid vociferous homage to a conquering Parisian.

The tricolor which waved in triumph over Lodi, Marengo and Austerlitz more than a century ago, floated proudly over the circus maximus of America. A modern Napoleon, ambitious, determined, daring and resourceful, was the hero of two continents.

As he vaulted from his silent car to receive the congratulations of foemen who made sincere hands speak for untutored lips and the osculatory demonstrations of his joyful and gesticulating helpers, the gallant Gaul seemed anything but fatigued, although his swarthy face was drawn and dirty, his twinkling eyes sunken and bloodshot, and his smiling lips cracked and parched. When the last hand had been clasped and the last kiss tendered, Goux grasped a bottle of champagne with the calloused numbed fingers that had guided the plunging Peugeot 200 times around the brick oval and drained the contents at one gulp. It was the seventh pint he had consumed in as many hours.

“But for the wine, I would have been unable to drive this race, “ he murmured as he smacked his lips.

In the immaculate evening dress of the boulevardier, Jules Goux had sipped the wine from the vineyards of France in the cafes and cabarets of Paris and called it “le bon vin.” In the grimy suit of the racing driver, Jules Goux gulped champagne at his pit and termed it a nectar, a nerve-sustaining potion that quickened the mind and eye, conquered fatigue and spurred on supreme desire.

Goux Takes Refreshments

“Wine is a mocker“ King Solomon wrote 3,000 years ago. “Wine is good,” Jules Goux cried at the conclusion of Friday’s 500-mile race. Here is an argument between two eminent authorities, each in „all his glory.” Which theory are we to accept? Perhaps both are right. Wine probably would have been a mocker had the American drivers drank it. No doubt its indulgence would have deadened their senses and tempted them to take chances which might have been fatal. But to the high-strung temperamental Goux, it was drink and food and a spur. Rich trophies and $20,000 in prize money he won and to the wine he drank, the victor gives credit.

Six bottles of champagne Goux gulped down while engaged in that Homeric struggle. Once a pitman dashed a cupful of the bubbling wine in Goux’s face as the Peugeot driver threw in his clutch and resumed his perilous flight after stopping at the pits for a tire. He grinned and wagged his head when thus baptised and rolled away with exhausts popping and motor barking defiance to challengers from America, Italy, England and Germany.

Castor Oil a Factor

But wine was only one of three liquid ingredients in that sensational victory.

There were gallons upon gallons of gasoline, gasoline of high test, blood for the steel-hearted, aluminium-veined monster that thundered to the front at the conclusion of the fortieth lap and held that proud position until the end of the race.

There was quart after quart of castor oil which, after mixing with the gasoline, sent up a nauseating, pungent incense to the gods of speed who favored the blue Peugeot and its daring driver in the race for international supremacy.

Champagne, castor oil and gasoline – this was the liquid combination that made the French invasion of America successful. But Goux praised only the juice of the grape. He lauded not the lethargic dinosaur of Mesozoic existence who, when transmogrified, became a fluid which rivals the swiftness of birds and aids in emulating their flight. He paid no tribute to the seeds of the Ricinus communis which when boiled and refined produce the oil that is more often found in the family medicine chest than in the tank of the motor car.

Goux’s statement as he gulped his seventh bottle of champagne is a testimonial for the wine agents to adopt, if nothing else. It also causes some idle speculation as to how the map of Europe would look to-day had the soldiers of the legion been served a few pints of the effervescing beverage on the red morning of June 15, 1815:

Vive le bon vin ! Vive le roi de vitesse !

At 10 o’clock in the morning America is expectant and confident. A scorching May sun, which looks like a colossal blotch of yellow ink on an expansive sheet of blue blotting paper, halos a scene which eclipses in grandeur the masterly stage setting of a Belasco. One hundred thousand worshippers are gathered in the temple of the speed gods—one hundred thousand fanatics who rise to their feet at the raucous chant of the announcers, one hundred thousand spectators who will acquire thrills, a coat of tan and an appetite as the red day wears on and the torrid sun mounts higher in the sky.

Five Nations Represented

In rows of four are twenty-six high-powered racing machines, the speed creations of the master engineering minds of America, France, England, Italy and Germany, a fleet flotilla of red, green, blue, yellow, grey, white and tan dreadnoughts. At the wheels sit the greatest of racing drivers, mad Mullahs who defy the fates and court death to win fame and fortune, flying Mercuries of stout hearts and taut nerves. The track is dry and red. Soon it will be slippery with oil where tires will slip and burn and the muscles of man be strained to conquer the skidding masses of steel.

There is a cheer. Eyes are directed to the roadway from the infield near the first turn. A green car rolls out on the track. It is the Keeton. Burman, who has worked all night replacing a broken steering knuckle, has entered the lists at the fifty-ninth second, a speed specter in white to defend America against the avaricious invaders—to start, to stop, to faint in his futile defense; then to recover and resume the chase.

A bomb explodes. There is a rattle of shifting gears, a deafening roar of impatient motors, a mighty cheer from many thousands. In a cloud of smoke the cars start away sounding a note of determination that will change to desperation before the last lap is turned. The struggle for the world’s speed supremacy is on. The split-second hand of a stopwatch becomes the moving pen that is to write a chapter of motor history.

Lap after lap is reeled off by the steel monsters as the watch hand turns monotonously. Like the blue bottles in the bar room song, car after car suddenly disappears. Some never pass the cheering stands again. They lie on the rim of the huge brick saucer, twisted, broken and foreboding. Others pass in shameful review, pushed by man instead of being driven by gasoline, to be docked at pit and garage, abandoned and cursed by drivers because of faithless rods, fickle bolts and faulty engines.

Fine Work by Cooper

Comes 4 o’clock. The odor of burning rubber pollutes the fresh spring air. Of the seven and twenty cars that rumbled and roared a strident challenge 6 hours before, only eleven are on the track, ten barking desperately after an arrogant blue leader which sounds a braggard’s note.

America now is skeptical but hopeful. The Peugeot’s roar sounds more menacing, more invincible on each lap, but Cooper, in the sturdy Stutz, is driving like a madman to save America’s plumed prestige and Cooper will succeed if daring and desire are the ingredients of victory. For Cooper is running like Hell—this is no profanity—he is running like Hell. But Cooper has slacked his thirst with lithia water. Champagne has wet the parched lips of Goux and awakened dormant ambition in his very heart, his very soul.

The Peugeot, the Napoleonic blue Peugeot, leads by 4½ minutes. There are but 20 miles more to run in the gruelling grind and the race will be over. Gil Anderson, the blood again flowing through the veins of his numbed hands, takes the wheel of the Stutz to drive his heart out, to drive his car to pieces in hopeless pursuit of the conquering Gaul.

Another half hour and the race is won. Goux is champion of the speedway. Anderson, tears streaming down his greasy cheeks, sees his foeman flash across the wire from the pits. The once-sturdy Stutz has been eliminated. Its challenging roar is silent. It stands, crippled and wasted near the victors of 1911 and 1912, Harroun’s Marmon and Dawson’s National.

America is downcast but cheering, for America is a good loser. One hundred thousand of its sons and daughters rise to their feet and pay homage to a slender hero in llama jacket, checkered knicker-bockers and brown doeskin puttees. Shutters of a score of cameras snap as he waves an American flag and gulps down a bottle of wine to celebrate his victory. France is once more supreme in the new world and Bacchus joins the gods of speed in their exultant revels.

The victory of Goux and the Peugeot was a surprise as well as a disappointment to American race critics who, admitting the French car to be fast and its driver efficient, prophesied that the blue machine would not be able to sustain the grind of 500 miles and that its pilot would be handicapped by the shortness of time in which he had to learn the peculiarities of the speedway.

Keeton a Contender

Condemned by the Peugeot team manager and consulting engineer of the Peugeot factory, M. Charles Faroux, as poorly balanced for the Indianapolis track, the French entrant was not considered as dangerous a contender as the English Sunbeam, which finished in fourth place. When Zuccarelli retired the No. 15 Peugeot on the twenty-first lap, after a gas line gave way and the carbureter caught fire, it looked as if the ominous prediction made before the start would be fulfilled and that Goux would be forced to dock his mount before the race was over.

The fact that both Goux and Zuccarelli regarded the Keeton as the most formidable ear in the race and that Goux took up the challenge of Burman early in the contest when Burman was leading the field, also satisfied the critics that they were justified in their prophecy that the holder of the 1-hour record would pound his car to pieces in his desire to keep on even terms with the pace-maker.

Even at the end of 350 miles, when Goux had a lead of two and one-half laps and had annexed the Remy brassard and Prest-O-Lite trophies by averaging 77.18 miles an hour in his flight over the slippery bricks, it was the common belief around the pits that the Peugeot was destined to meet the same fate that de Palma’s Mercedes did a year before.

„It’ll drop out soon after running 400 miles,” was the confident prediction of the men in the Stutz pit, who were watching the Sunbeam and Mercedes-Knight with more concern at that stage of the race than the plunging Peugeot.

But predictions are like $5 bills and New Year’s resolutions. They are broken more often than they are kept. Goux did not follow Zuccarelli to the grey garage, pushing a disabled car before him. The slender Frenchman did not burn up his tires in going into the turns or pound his machine to pieces in shaking off the determined challenge of Anderson, Mulford and Merz. He won the Wheeler & Schebler cup when he crossed the wire for the one hundred and sixtieth time and maintained his early pace of 77 miles an hour with few variations until the end.

Gil Anderson Prominent

Although the early pace set by Burman when he averaged 79 miles an hour for 100 miles seemed to trouble the impetuous Goux, the Frenchman only had one serious contender, Gil Anderson, after the Keeton caught fire on the fifty-fifth lap. The driver of the No. 3 Stutz, although trailing two and one-half laps, looked exceptionally dangerous and was in a position to forge to the front should predictions hold and the Peugeot be forced to stop for repairs. Near the close of the race, Anderson, his hands bleeding and his strength almost exhausted, was relieved by Earl Cooper. As when Patschke took the wheel of the Marmon in 1911 and Herr went to the driver’s seat of Dawson’s National last year, Cooper shoved the gas lever up several notches and sent the consistent white car after the blue invader. It was a spectacular chase. The Stutz responded as if human. Cooper gained on every lap. With 50 miles yet to run, the Stutz was but 4½ minutes behind the Peugeot and a stop for a tire by Goux would give Anderson, who again took the wheel of the plucky Stutz, the lead, perhaps victory.

But the Peugeot did not stop. It was Agan, Anderson’s mechanician, not Begin, who rode with Goux, that held up his right hand as the Stutz thundered by in its desperate chase after the foreign machine. The next time around the Stutz stopped. So did its engine. A rear tire change was made in less than a minute. Hope was not dead yet, but the motor was, and after five sweating, swearing pitmen had turned the crank lever in vain for fully 3 minutes, the white car was pushed into the oblivion of the infield with a broken camshaft gear. As it rumbled with shame over the grass, its wheels crushed the last chance of an American victory.

Much of the credit for the showing of the Mercer, which finished in second place nearly 14 minutes behind the conquering Peugeot, must be given to Ralph de Palma, child of misfortune, from whose hands the fates snatched victory in last year’s race. The same fates rode with him on Friday in the No. 21 Mercer and again made the hood a Pandora’s box when a cylinder cracked early in the speed struggle. De Palma wheeled the yellow car to the sheds and returned to the pits to relieve Bragg and Wishart, his teammates. With the race half over and Bragg’s car trailing too far to be a contender, the Italian took the wheel of Wishart’s machine and brought the Mercer from ninth to third place before turning it over to Wishart for the final laps of the struggle.

Goux Shows Great Skill

Goux proved himself a master at the wheel from the time the bomb was fired until the checkered flag was waved. He was daring but not too daring. He took the turns like a Harroun or Dawson, drivers that know every one of the 3,500,000 bricks in the speedway. He curbed his natural impetuosity to open up when high speed was unnecessary.

There was a master mind in the Peugeot pit, as there was a mastermind at the Peugeot wheel. It was Johnny Aitken, former National racing manager, who acted as a governing valve on Goux’s Gallic impetuosity. Moreover, Goux obeyed Aitken’s signals. When “Retardez‘ showed in letters of white on the black board, the Frenchman restrained his desires and slowed down. At the signal “ Allons“- it was rarely given – he smiled as he stepped on the throttle and urged the willing Peugeot on to pass its competitors.

Considering the unfriendly intensity of the sun, the little practice he has had and the tire troubles he encountered in warmup his car, Goux made but few stops for shoes. He signalled for new rubber but nine times, a phenomenal record compared to his showing in practice when he averaged but four laps to a tire.

Race Develops Heroes

The 500-mile race is a mold in which heroes are cast. Pigmymen enter it and emerge Titans. It is a contest that breaks hearts, shatters nerves and puts fortitude to the acid test. It always has been, it always will be and the 1913 classic is no exception. Charles Merz, driver of No. 2 Stutz, disobeyed orders. Because he did, his hands are burned, but the car he drove finished third and he won $5,000 by his daring. He was in fourth place at the end of the one hundred and eightieth lap and when Anderson was forced to retire, moved up automatically to third position. For over 100 miles he had been running desperately, refusing to give a second.

Gradually gaining inches when miles were needed to make him victor, Merz was given the green flag after the Mercer started on its last lap. As he crossed the wire the front of his car was aflame. Stutz pitmen waved him in. Between $5,000 and Merz, they chose the man. Merz saw the frantic signals but did not heed them. In a veritable chariot of fire he drove the final 242 miles, his mechanician, Martin, lying across the hood and beating at the flames with his bare hands. There is something to admire in men like Merz and Martin, men who never quit.

There were few spectators in the cheering stands who knew who Stevens was at the start of Friday’s race. He was an unknown, this big-hearted, never-quit boy who rode beside Ralph Mulford, vice Billy Chandler, smiling Ralph’s former mechanician who this spring was promoted to relief driver on the Mercer team. It was Stevens‘ first 500-mile race, but he was equal to the ordeal, more than equal, as he proved near the close of the struggle.

Laying back at the start, Mulford gradually bettered his position as he reeled off lap after lap and at the end of 250 miles he was in third place. He had not made a stop at his pits and his motor was sounding a menacing challenge. Mulford took on fuel after running 275 miles, breaking all records for nonstop competition, and then was the victim of the „unexpected something” that always happens in a motor car race. With third place practically clinched, Mulford ran out of gasoline on the back stretch. Leaping from the exhausted Mercedes, Stevens started for the pits, more than a mile away. Seconds are precious in a struggle where $50,000 is at stake. Stevens may have been a tyro, but he knew that. Darting through the crowds of the infield, stumbling and falling in the high grass, jumping fences and creeks of sluggish water, the modern Pheidipprides raced to the pits, staggered over the pit rail so as not to be disqualified, cried “Ralph’s out of gas“ and fell in a faint, while another mechanic ran back to Mulford.

Photo captions.

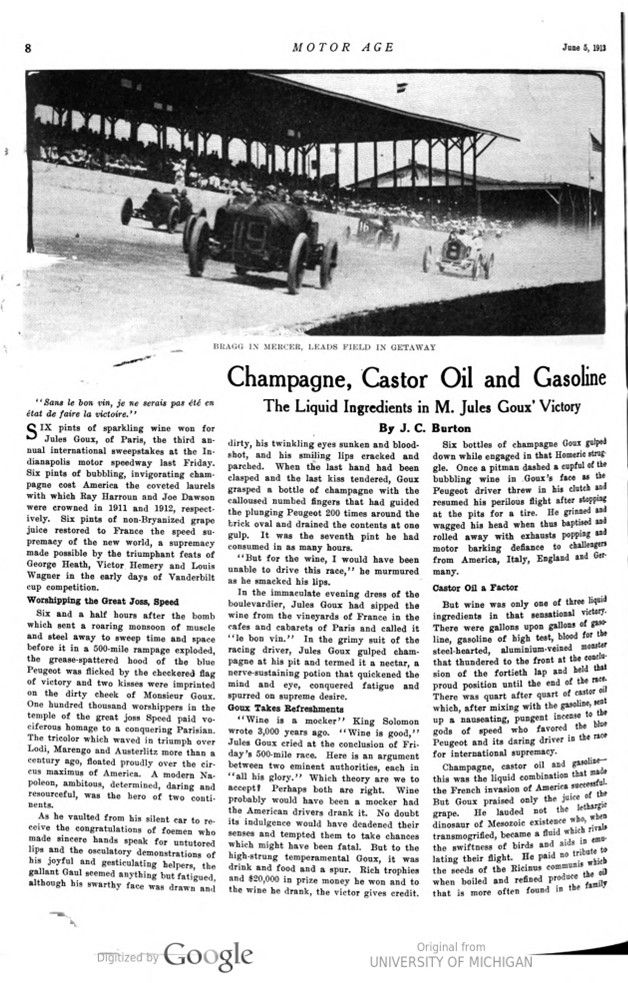

Page 8. – BRAGG IN MERCER, LEADS FIELD IN GETAWAY

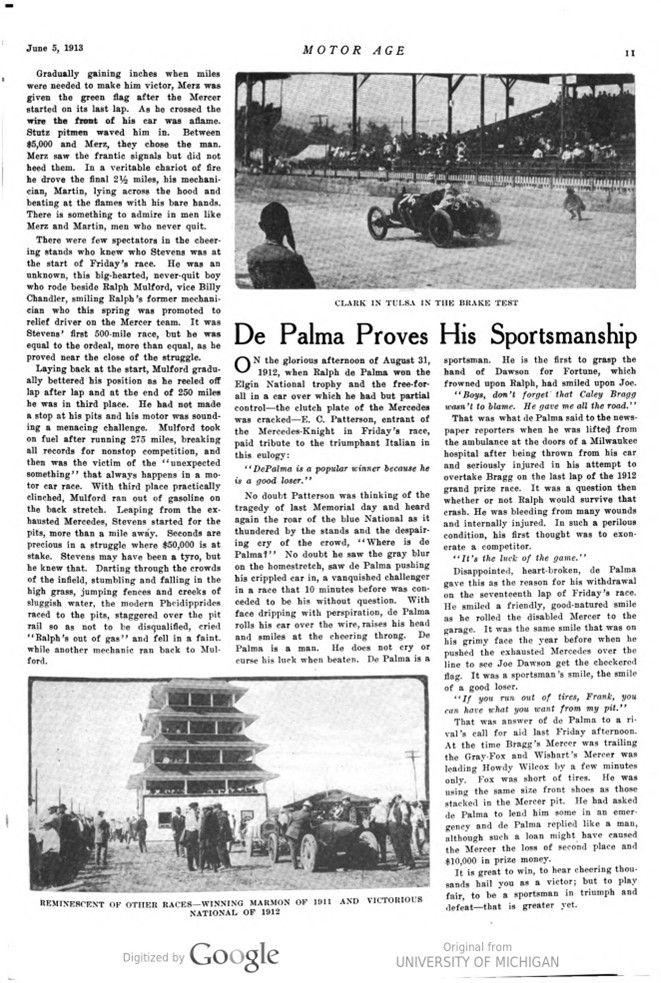

Page 9. – GOUX STOPS FOR CHAMPAGNE AT THE PITS (Photograph by Underwoos & Underwood, New York)

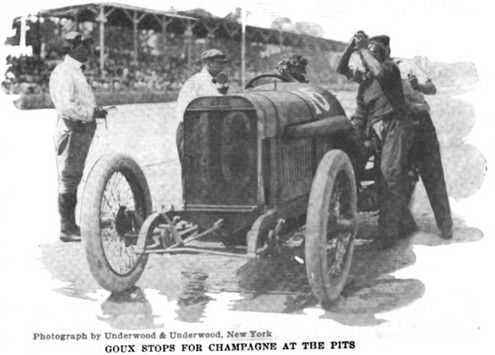

Page 10. – VIEW OF PADDOCK SHOWING PARKING SPACES AND THE PITS

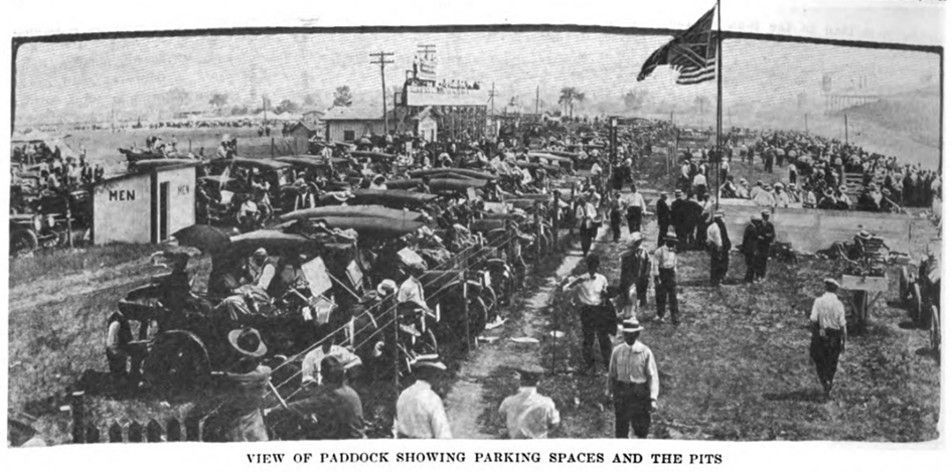

Page 11. – REMINESCENT OF OTHER RACES _ WINNING MARMON OF 1911 AND VICTORIOUS NATIONAL OF 1912