The very well known American journalist C. G. Sinsabaugh wrote this summarizing article on the 500-mile tace. Although a French driver in a French car was the winner of this third Sweepstakes (Jules Goux in Peugeot), the next two were American drivers. Second finished Spencer Wishart in Mercedes; an American driver in a German car. Third came Merz in a Stutz; an American driver in an American car. Slow but steady, American drivers and cars were catching in on their European counterparts.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

MOTOR AGE Vol. XXIII, No. 23 Chicago, June 2, 1913

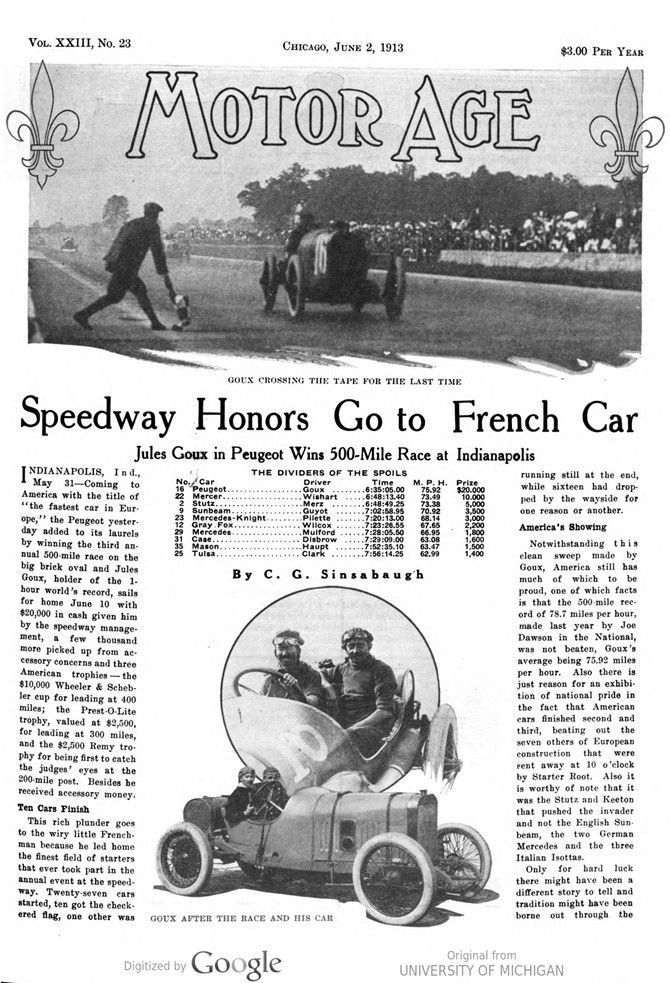

Speedway Honors Go to French Car

Jules Goux in Peugeot Wins 500-Mile Race at Indianapolis

By C. G. Sinsabaugh

INDIANAPOLIS, Ind., May 31 – Coming to America with the title of „the fastest car in Europe,“ the Peugeot yesterday added to its laurels by winning the third annual 500-mile race on the big brick oval and Jules Goux, holder of the 1- hour world’s record, sails for home June 10 with $20,000 in cash given him by the speedway management, a few thousand more picked up from accessory concerns and three American trophies – the $10,000 Wheeler & Schebler cup for leading at 400 miles; the Prest-O-Lite trophy, valued at $2,500, for leading at 300 miles, and the $2,500 Remy trophy for being first to catch the judges‘ eyes at the 200-mile post. Besides he received accessory money.

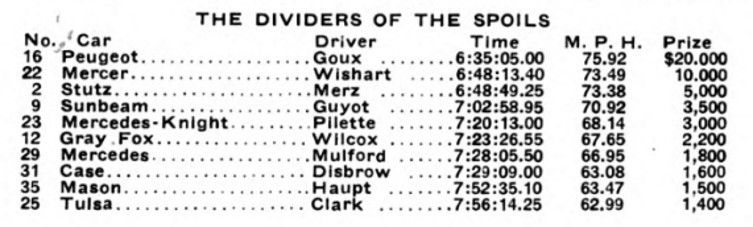

Ten Cars Finish

This rich plunder goes to the wiry little Frenchman because he led home the finest field of starters that ever took part in the annual event at the speedway. Twenty-seven cars started, ten got the checkered flag, one other was running still at the end, while sixteen had dropped by the wayside for one reason or another.

America’s Showing

Notwithstanding this clean sweep made by Goux, America still has much of which to be proud, one of which facts is that the 500-mile record of 78.7 miles per hour, made last year by Joe Dawson in the National, was not beaten, Goux’s average being 75.92 miles per hour. Also there is just reason for an exhibition of national pride in the fact that American cars finished second and third, beating out the seven others of European construction that sent away at 10 o’clock by Starter Root. Also it is worthy of note that it was the Stutz and Keeton that pushed the invader and not the English Sunbeam, the two German Mercedes and the three Italian Isotta’s.

Only for hard luck there might have been a different story to tell and tradition might have been borne out through the victory of a Stutz. That Gill Anderson in a Stutz was not in at a fighting finish was due to a broken camshaft after he had run a grueling race and it looked as if the Peugeot might have to look to its laurels. It was no walkover for Goux by any means.

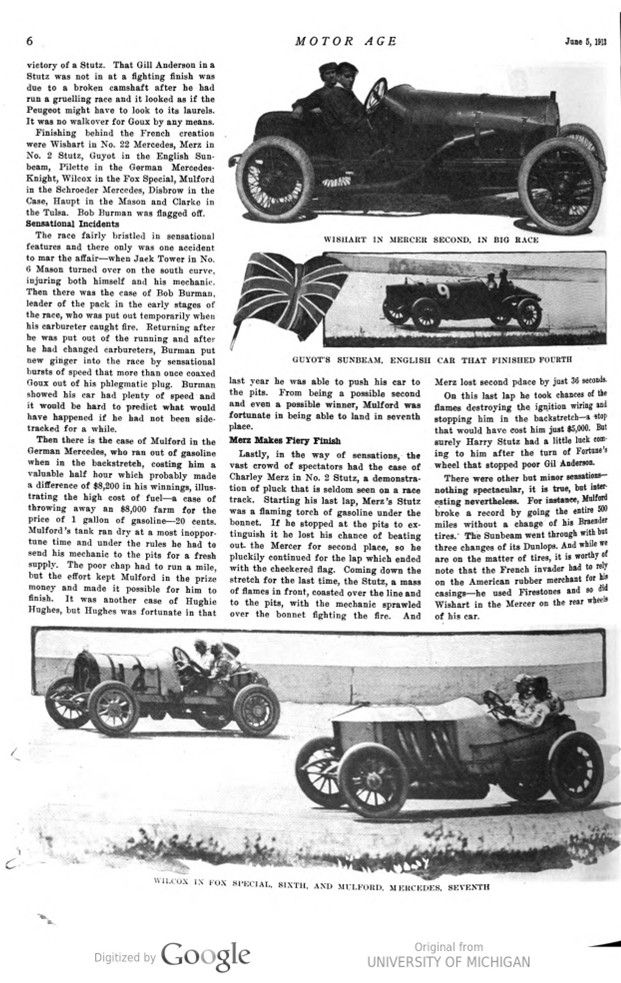

Finishing behind the French creation were Wishart in No. 22 Mercedes, Merz in No. 2 Stutz, Guyot in the English Sunbeam, Pilette in the German Mercedes-Knight, Wilcox in the Fox Special, Mulford in the Schroeder Mercedes, Disbrow in the Case, Haupt in the Mason and Clarke in the Tulsa. Bob Burman was flagged off.

Sensational Incidents

The race fairly bristled in sensational features and there only was one accident to mar the affair – when Jaek Tower in No. 6 Mason turned over on the south curve, injuring both himself and his mechanic. Then there was the case of Bob Burman, leader of the pack in the early stages of the race, who was put out temporarily when his carbureter caught fire. Returning after he was put out of the running and after he had changed carbureters, Burman put new ginger into the race by sensational bursts of speed that more than once coaxed Goux out of his phlegmatic plug. Burman showed his car had plenty of speed and it would be hard to predict what would have happened if he had not been sidetracked for a while.

Then there is the case of Mulford in the German Mercedes, who ran out of gasoline when in the backstretch, costing him a valuable half hour which probably made a difference of $8,200 in his winnings, illustrating the high cost of fuel – a case of throwing away an $8,000 farm for the price of 1 gallon of gasoline – 20 cents. Mulford’s tank ran dry at a most inopportune time and under the rules he had to send his mechanic to the pits for a fresh supply. The poor chap had to run a mile, but the effort kept Mulford in the prize money and made it possible for him to It was another case of Hughie finish. Hughes, but Hughes was fortunate in that last year he was able to push his car to the pits. From being a possible second and even a possible winner, Mulford was fortunate in being able to land in seventh place.

Merz Makes Fiery Finish

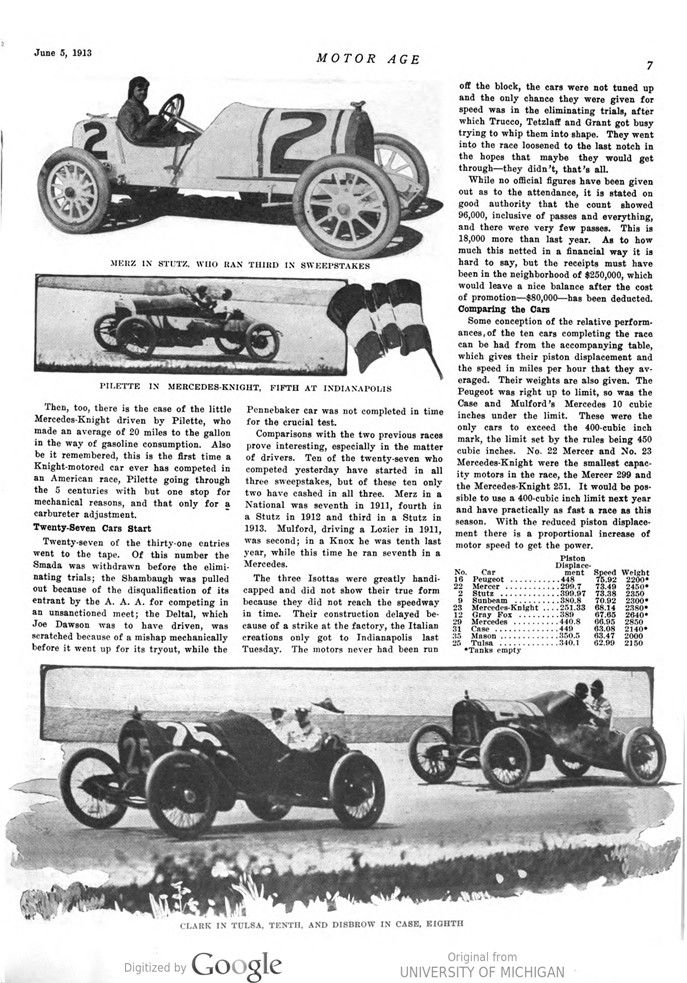

Lastly, in the way of sensations, the vast crowd of spectators had the case of Charley Merz in No. 2 Stutz, a demonstration of pluck that is seldom seen on a racetrack. Starting his last lap, Merz’s Stutz was a flaming torch of gasoline under the bonnet. If he stopped at the pits to extinguish it, he lost his chance of beating out. the Mercer for second place, so he pluckily continued for the lap which ended with the checkered flag. Coming down the stretch for the last time, the Stutz, a mass of flames in front, coasted over the line and to the pits, with the mechanic sprawled over the bonnet fighting the fire. And Merz lost second place by just 36 seconds.

On this last lap he took chances of the flames destroying the ignition wiring and stopping him in the backstretch – a stop that would have cost him just $5,000. But surely Harry Stutz had a little luck coming to him after the turn of Fortune’s wheel that stopped poor Gil Anderson.

There were other but minor sensations – nothing spectacular, it is true, but interesting, nevertheless. For instance, Mulford broke a record by going the entire 500 miles without a change of his Braender tires. The Sunbeam went through with but three changes of its Dunlops. And while we are on the matter of tires, it is worthy of note that the French invader had to rely on the American rubber merchant for his casings he used Firestones and so did Wishart in the Mercer on the rear wheels of his car.

Then, too, there is the case of the little Mercedes-Knight driven by Pilette, who made an average of 20 miles to the gallon in the way of gasoline consumption. Also be it remembered, this is the first time a Knight-motored car ever has competed in an American race, Pilette going through the 5 centuries with but one stop for mechanical reasons, and that only for a carbureter adjustment.

Twenty-Seven Cars Start

Twenty-seven of the thirty-one entries went to the tape. Of this number the Smada was withdrawn before the eliminating trials; the Shambaugh was pulled out because of the disqualification of its entrant by the A. A. A. for competing in an unsanctioned meet; the Deltal, which Joe Dawson was to have driven, was scratched because of a mishap mechanically before it went up for its tryout, while the Pennebaker car was not completed in time for the crucial test.

Comparisons with the two previous races prove interesting, especially in the matter of drivers. Ten of the twenty-seven who competed yesterday have started in all three sweepstakes, but of these ten only two have cashed in all three. Merz in a National was seventh in 1911, fourth in a Stutz in 1912 and third in a Stutz in 1913. Mulford, driving a Lozier in 1911, was second; in a Knox he was tenth last year, while this time he ran seventh in a Mercedes.

The three Isotta’s were greatly handicapped and did not show their true form because they did not reach the speedway in time. Their construction delayed because of a strike at the factory, the Italian creations only got to Indianapolis last Tuesday. The motors never had been run off the block, the cars were not tuned up and the only chance they were given for speed was in the eliminating trials, after which Trucco, Tetzlaff and Grant got busy trying to whip them into shape. They went into the race loosened to the last notch in the hopes that maybe they would get through-they didn’t, that’s all.

While no official figures have been given out as to the attendance, it is stated on good authority that the count showed 96,000, inclusive of passes and everything, and there were very few passes. This is 18,000 more than last year. As to how much this netted in a financial way it is hard to say, but the receipts must have been in the neighborhood of $250,000, which would leave a nice balance after the cost of promotion-$80,000-has been deducted.

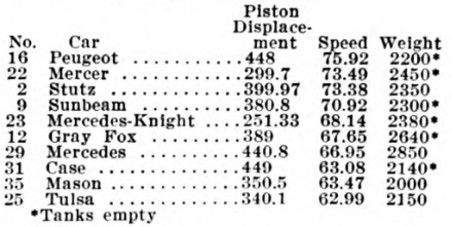

Comparing the Cars

Some conception of the relative performances, of the ten cars completing the race can be had from the accompanying table, which gives their piston displacement and the speed in miles per hour that they averaged. Their weights are also given. The Peugeot was right up to limit, so was the Case and Mulford’s Mercedes 10 cubic inches under the limit. These were the only cars to exceed the 400-cubic inch mark, the limit set by the rules being 450 cubic inches. No. 22 Mercer and No. 23 Mercedes-Knight were the smallest capacity motors in the race, the Mercer 299 and the Mercedes-Knight 251. It would be possible to use a 400-cubic inch limit next year and have practically as fast a race as this season. With the reduced piston displacement there is a proportional increase of motor speed to get the power.

Photo captions.

Page 5. GOUX CROSSING THE TAPE FOR THE LAST TIME – GOUX AFTER THE RACE AND HIS CAR – THE DIVIDERS OF THE SPOILS

Page 6. WISHART IN MERCER SECOND, IN BIG RACE – GUYOT’S SUNBEAM, ENGLISH CAR THAT FINISHED FOURTH – C. WILCOX IN FOX SPECIAL, SIXTH, AND MULFORD, MERCEDES, SEVENTH

Page 7. MERZ IN STUTZ, WHO RAN THIRD IN SWEEPSTAKES – PILETTE IN MERCEDES-KNIGHT, FIFTH AT INDIANAPOLIS – CLARK IN TULSA, TENTH, AND DISBROW IN CASE, EIGHTH