Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

Motor Age, Vol. XLV, No. 23, June 5, 1924, page 9 – 11

98.24 M. P. H. Sets New Record for Speedway Race

First Five to Finish in Twelfth International Sweepstakes Exceeded Highest Average Speed Heretofore

Duesenberg Driven by Corum and Boyer Wins – Cooper Second in Studebaker Special – Murphy Third

By SAM SHELTON

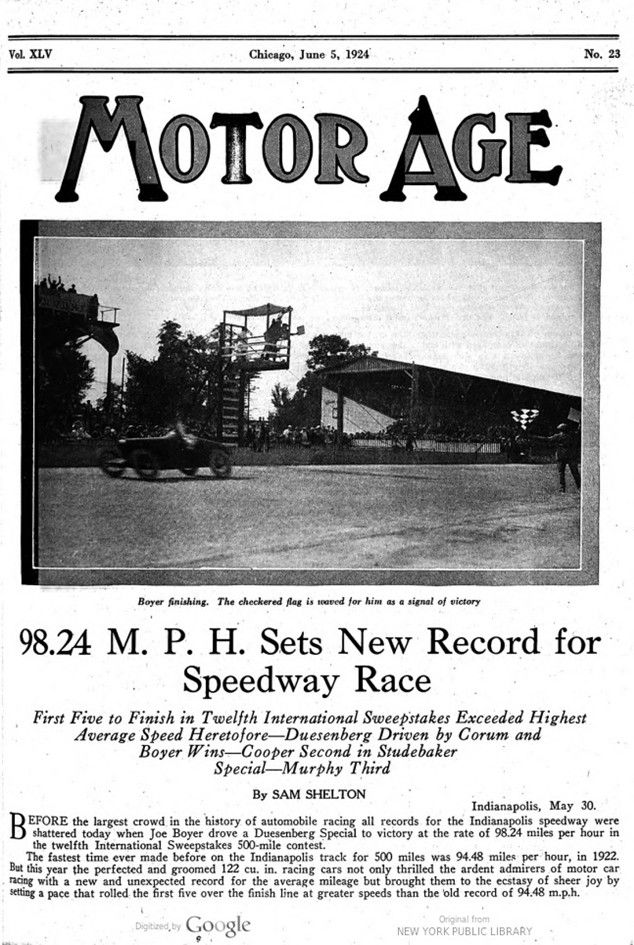

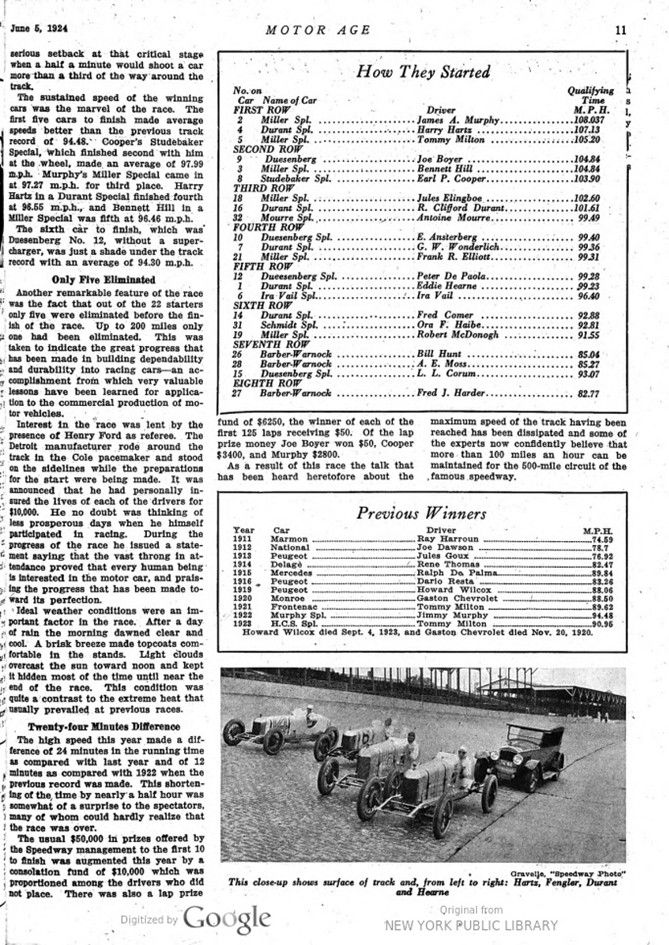

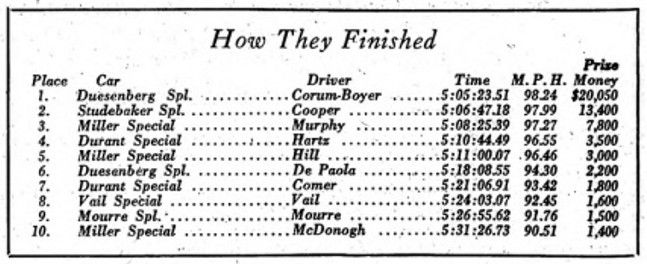

INDIANAPOLIS, May 30. – BEFORE the largest crowd in the history of automobile racing all records for the Indianapolis speedway were shattered today when Joe Boyer drove a Duesenberg Special to victory at the rate of 98.24 miles per hour in the twelfth International Sweepstakes 500-mile contest.

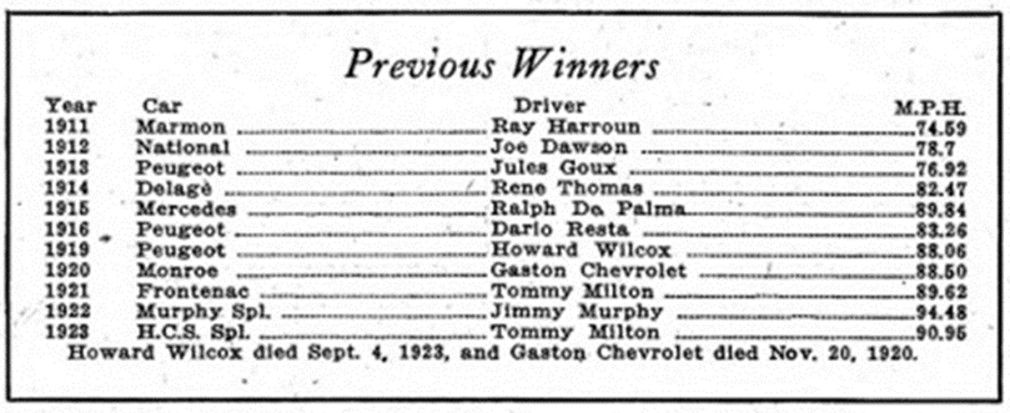

The fastest time ever made before on the Indianapolis track for 500 miles was 94.48 miles per hour, in 1922. But this year the perfected and groomed 122 cu. in. racing cars not only thrilled the ardent admirers of motor car racing with a new and unexpected record for the average mileage but brought them to the ecstasy of sheer joy by setting a pace that rolled the first five over the finish line at greater speeds than the old record of 94.48 m.p.h.

The outcome of this year’s race was especially brilliant as compared with last year when a backward step was taken with an average of only 90.95 m.p.h. for the winner, Tommy Milton in an H. C. S. Special.

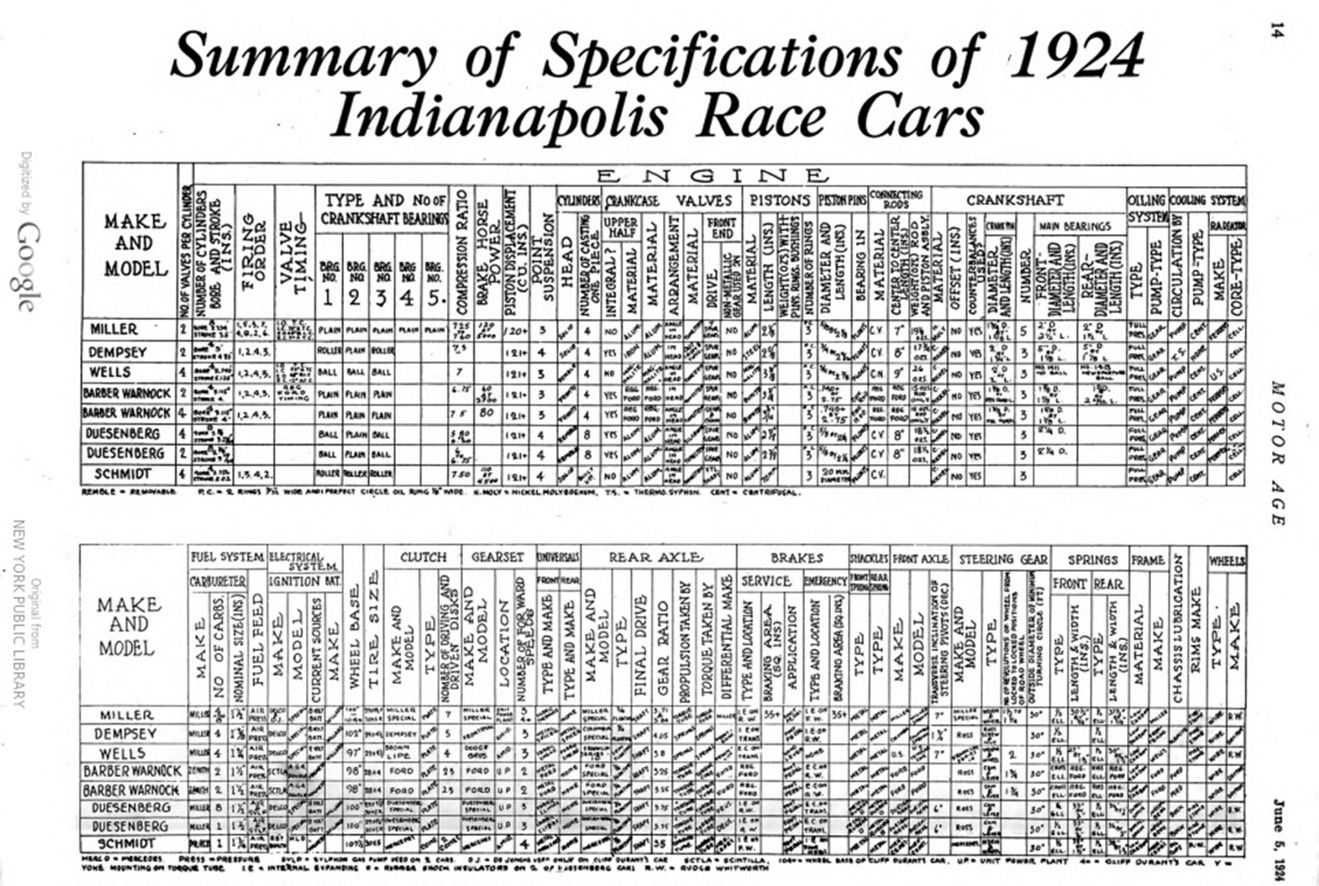

Sharing the glory of today’s victory with Joe Boyer is L. L. Corum, who drove the victorious Duesenberg the first 109 laps of its whirlwind course and by his steady work kept it within striking distance of the first place. And of course Fred Duesenberg, designer and builder of this car, the first American racing car to be equipped with a supercharger, comes in for his share of the honor attending the hard-earned victory and tonight received the congratulations of many friends and plucky opponents who have watched his determined efforts toward the perfection of a master speed creation.

But the Duesenberg victory was not a walk-away. It was the bitterly contested, dashing, fluctuating, tense, dogged, persistent, thrilling thing that the lovers of the automobile like to see, with fortune frowning and then smiling upon the little demons of velocity.

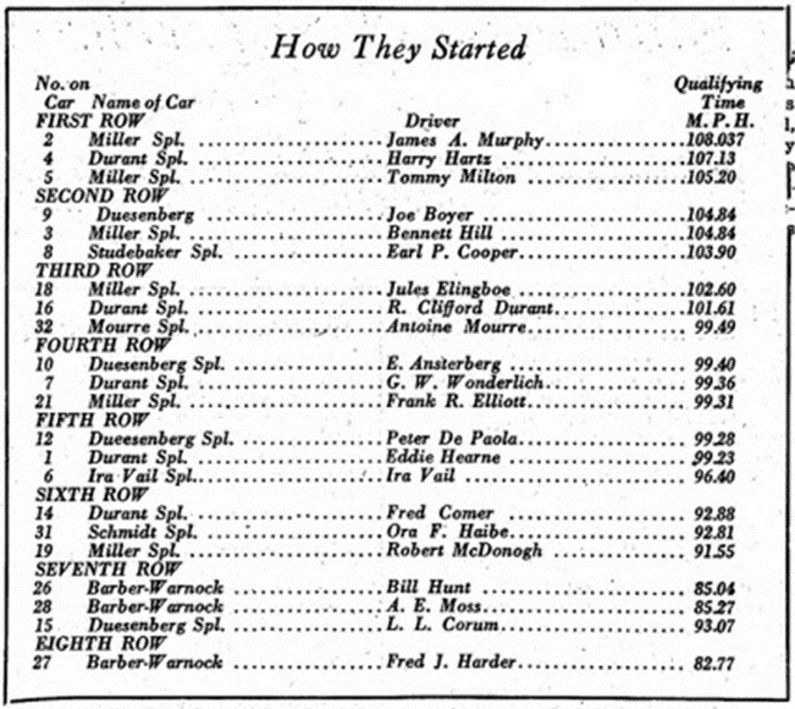

It was not until near the end of the race that the Duesenberg car No. 15 with Boyer driving grabbed the lead. Up to that time the Duesenberg record, with four entries, had been first brilliant, then disappointing, then determined, but not especially hopeful. Boyer started the race driving the Duesenberg entry No. 9, a car that had qualified at 104 m.p.h. and which was the pet of the master designer himself. Like a flash of light, a rush of wind, this car jumped to the front in the first lap and completed the first circuit with its tail fanning a breeze for the nimble Jimmy Murphy in his Miller Special.

It was a start such as Indianapolis had never before witnessed and the stands went wild with the joy of it – and the whisper passed. „It’s the supercharger.“ And it was the supercharger. In this great burst of speed Joe Boyer had the misfortune to shear a key in one of the supercharger gears and this little secret booster of speed was put out of commission. Thereafter Duesenberg No. 9 trailed until when near the end of the race it was put out of commission by being driven into the retaining wall by a driver who had relieved Boyer.

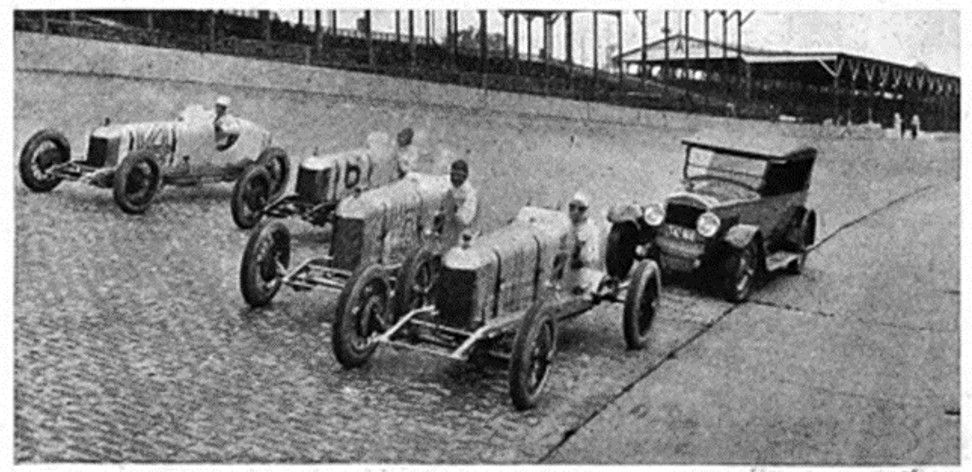

With Boyer’s car out of the way and the driver himself dropped from the scene for the time, Jimmy Murphy found it fairly easy to keep the lead, but somehow he couldn’t get very far in front of the little green Studebaker Special which had Earl Cooper for its pilot. Lap after lap the two and a half mile circuit was made with Murphy leading, Cooper second and Bennett Hill third in a Miller Special, and less than a minute separated the first from the third.

A Speed Burst

Somewhere near 140 miles one of the most beautiful speed bursts of the race was seen when Cooper who had been drawing closer to Murphy chased him down the stretch in front of the grandstands and nosed in front of him as they passed the starter’s stand. On the next lap, however, Murphy regained his lead but held it for only one time around During all this time Cooper. Murphy and Hill were the leaders, with positions shifting occasionally. Corum in the Duesenberg Special No. 15 was holding pretty consistently to fourth place, but not attracting much notice.

Cooper’s first stop was made at his 104th lap and this allowed Murphy to go ahead, but not for long. Cooper was soon again in the lead and at 325 miles the order was Cooper, Murphy, Boyer, Hill, Hartz.

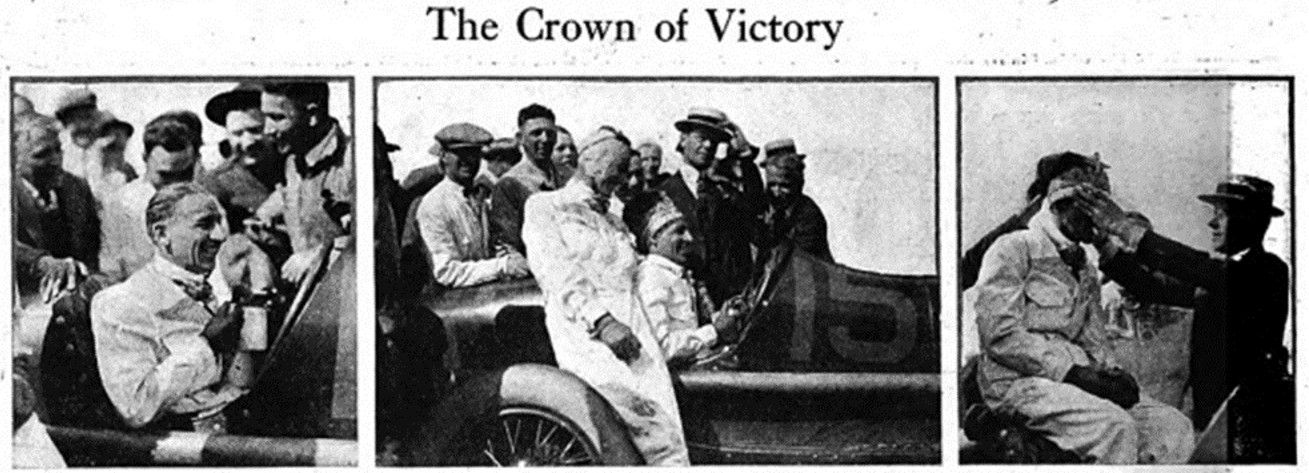

Corum had driven his Duesenberg No. 15 into the pits at his 109th lap for a change of three tires and Boyer had relieved him as driver. Fred Duesenberg is said to have instructed him to „put that ship out in front or burn it up.“ At any rate something happened and from that time on the supercharger Duesenberg whirled steadily toward first place. Good fortune, too, smiled upon it, for not once again did it stop until the crown of victory had been won. And with it a purse of some twenty thousand useful dollars.

The turn of what looked like an ill trick of fate against the Duesenbergs into smashing and startling victory brought enthusiastic applause from the throngs, but in it was a note of regret that the one to suffer had to be plucky Earl Cooper whose driving was perfect and whose car lacked nothing in speed. Toward the end of the race when he still had a chance to win Cooper had to make two stops for tire changes and although the time consumed in the changes was probably less than 30 seconds it was a serious setback at that critical stage when a half a minute would shoot a car more than a third of the way around the track.

The sustained speed of the winning cars was the marvel of the race. The first five cars to finish made average speeds better than the previous track record of 94.48. Cooper’s Studebaker Special, which finished second with him at the wheel, made an average of 97.99 m.p.h. Murphy’s Miller Special came in at 97.27 m.p.h. for third place. Harry Hartz in a Durant Special finished fourth at 96.55 m.p.h., and Bennett Hill in a Miller Special was fifth at 96.46 m.p.h.

The sixth car to finish, which was Duesenberg No. 12, without a supercharger, was just a shade under the track record with an average of 94.30 m.p.h.

Only Five Eliminated

Another remarkable feature of the race was the fact that out of the 22 starters only five were eliminated before the finish of the race. Up to 200 miles only one had been eliminated. This taken to indicate the great progress that has been made in building dependability and durability into racing cars – an accomplishment from which very valuable lessons have been learned for application to the commercial production of motor vehicles.

Interest in the race was lent by the presence of Henry Ford as referee. The Detroit manufacturer rode around the track in the Cole pacemaker and stood on the sidelines while the preparations for the start were being made. It was announced that he had personally insured the lives of each of the drivers for $10,000. He no doubt was thinking of less prosperous days when he himself participated in racing. During the progress of the race he issued a statement saying that the vast throng in attendance proved that every human being is interested in the motor car, and praising the progress that has been made toward its perfection.

Ideal weather conditions were an important factor in the race. After a day of rain the morning dawned clear and cool. A brisk breeze made topcoats comfortable in the stands. Light clouds Overcast the sun toward noon and kept it hidden most of the time until near the end of the race. This condition was quite a contrast to the extreme heat that usually prevailed at previous races.

Twenty-four Minutes Difference

The high speed this year made a difference of 24 minutes in the running time as compared with last year and of 12 minutes as compared with 1922 when the previous record was made. This shortening of the time by nearly a half hour was somewhat of a surprise to the spectators, I many of whom could hardly realize that the race was over.

The usual $50,000 in prizes offered by the Speedway management to the first 10 to finish was augmented this year by a consolation fund of $10,000 which was proportioned among the drivers who did not place. There was also a lap prize fund of $6250, the winner of each of the first 125 laps receiving $50. Of the lap prize money Joe Boyer won $50, Cooper $3400, and Murphy $2800.

As a result of this race the talk that has been heard heretofore about the maximum speed of the track having been reached has been dissipated and some of the experts now confidently believe that more than 100 miles an hour can be maintained for the 500-mile circuit of the famous speedway.