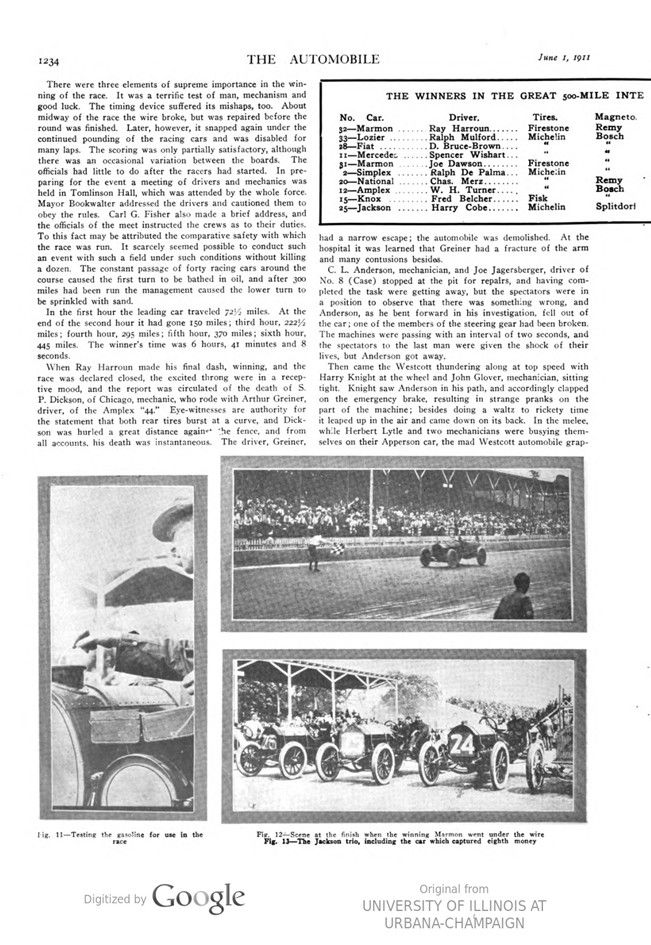

An extended report of the first Indianapolis 500 mile race, highlighting the race in itself and the several finishers. It adresses also several cars as Mercedes, Case, Westcott, Fiat and the winning Marmon; the race incident and the issues with the race timing.

Text and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

THE AUTOMOBILE. Vol. XXIV, No. 22, June 1, 1911

500-Mile Sweepstakes Run Off at the Indianapolis Speedway

Marmon Home with the Bacon — Lozier is a Close Second-Fiat on the Rind

INDIANAPOLIS, May 30. — In the greatest automobile race ever run so far in the history of the industry, the Marmon entry No. 32 won the 500-mile International Sweepstakes to-day from the greatest field that ever faced a starter. The car was driven by Ray Harroun, whose retirement from automobile racing has been periodically announced. The Marmon led for more than 300 miles, but at no time was far in advance of its rivals.

Lozier, No. 33, driven by Ralph Mulford, was a good second, and but for some slow and clumsy work at the pits might have given the winner a little stronger argument. Third place was taken by a Fiat car, driven by David L. Bruce-Brown. A mechanical mishap in the final round prevented a better showing.

The specially-built 200 h. p. Mercedes, which is said to have cost Spencer Wishart $63,000, finished in fourth position, driven by Mr. Wishart. In fifth place came Simplex car No. 2, driven by De Palma, while in order following were National 20 (Merz), Amplex 12 (Turner), Jackson 25 (Cobe), Knox (Belcher) and Mercer (Hughes).

When the finishing flag had been waved for these there were still fourteen other contestants on the track. It was a glorious day, cool and varied by alternate sunshine and clouds. There was sufficient breeze to make even Indianapolis bearable, and almost 100,000 persons paid admission to the Speedway to witness the contest. It was a day of thrills, in which the climax came just before the leading car passed the half-way mark.

For one tense instant 80,000 persons breathed groans of anguish as four cars piled themselves up in a tangled heap at the south end of the pits.

It was a moment pregnant with possibilities, and it marked the birth of a new hero. Case car No. 8 broke the steering knuckle passing the stand on its 87th round, and the car careered against the retaining wall in front of the judges‘ stand. Wobbling uncertainly, the car started out to mid-track, where with a lurch it threw L. Anderson, the mechanic, sideways from his seat. Running like a watch and well up with the leaders was the Westcott car No. 7, driven by Harry Knight. He was too close to the prostrate Anderson to avoid some sort of a disaster, and he chose to let himself and his car bear the brunt of it. With a powerful whirl of his steering wheel, Knight headed his car to the left and darted straight into the side of Apperson No. 35, which was undergoing tire changes. There was a terrific crash, which was witnessed by all the thousands ranged along the straightway. The Apperson turned over, throwing Herbert Lytle twenty-five feet and injuring his mechanic. The injured Westcott car turned end for end in the air and dropped upon Fiat 18, which was standing south of the pits having a ’new drag rod installed. The impact was so great that it moved the structure of the pits like the bending of a bow.

For a moment it looked as if the race was finished right there, and the officials strove desperately to check the contesting cars.

But the work of the Westcott had cleared the track of obstacles, and in another moment the signal to go ahead was given. Marvelous it may seem, nobody was seriously injured in this smash. The Westcott car would certainly have been among the leaders at the end had it maintained its excellent running. In practically 240 miles it had changed but two tires.

The start of the race was one of the most interesting things about it. The field of forty was lined up in ranks of five, between which 100-foot intervals were allowed. On the left of the front rank was Carl G. Fisher, President of the Speedway Company, in his Stoddard-Dayton roadster, acting as pacemaker. When the word was given the cars moved out, keeping almost alignment at a rate said to be 40 miles an hour. All around the big oval the ranks swept in platoon formation until they reached the head of the stretch. There they closed distance, and before reaching the starting point each driver pr ed himself to take the position he wished in the opening round.

At the wire Mr. Fisher pulled out to the left, and the starting flag and bomb sent the field away on its long grind. National car No. 4 showed first in the lead, maintaining the pace for about three laps. The Mercedes entry then took up the running and stayed out in front for eight laps. Knox No. 15, which, by the way made the best showing of any Knox car so far in the supreme tests of speed and endurance, displaced the Mercedes and led at the end of thirty miles. Fiat No. 28, driven by Bruce-Brown, took up the running at this point, and with the exception of a momentary faltering which allowed National No. 4 and then Simplex No. 2 to lead for a little while, this car made the pace until half the journey was over. At one time No. 28 had a lead of 7½ miles. Reaching the half-way mark, the long, narrow, six-cylinder Marmon, guided by the veteran Harroun, glided into the lead and from there to the coveted point at which the magpie flag announced the winner the sturdy Wasp stayed out in front. It was a fierce struggle all the way in, and the winner did its work so silently that few in the stands realized what was happening until it happened. Sitting all alone in the narrow cockpit of the Wasp and trusting to an adjustable mirror placed just in front of his eyes to warn him of the approach of any of his rivals from the rear, Harroun drove a masterly race. He was assisted in his work by Cyrus Patschke, who took the wheel for about 100 miles when the Marmon was working its way through to the front. Patschke also assisted in driving the four-cylinder Marmon No. 31 when Dawson required relief. The winner experienced no mechanical difficulty, and went through with only four tire changes. The first prize and the prizes for which the car was eligible among the list offered by the accessory makers amounted to $14,250.

The Lozier, which came second, was always prominent. Fourth place was as far back as the car was at any time after the ninetieth mile. In the last fifty miles Mulford kept shooting it along at better than 80 miles an hour, which naturally caused him to call at the pits for new tires rather frequently. Tire changes at the Lozier pit were not as fast as those enjoyed by others of the contestants. The replacement of a wheel proved costly in time to this car.

Fiat 28 and Mercedes II, the next two to finish, did their prettiest all the way. The foreign cars ran splendid races, but they were not good enough to win. Neither experienced special mechanical troubles until the mishap to the Fiat in the last round, which was the breaking of the spark lever on the wheel. Simplex No. 2 (De Palma), prominent throughout except for a few rounds while a new wheel was working into condition, was a distant fifth. The showing of the National trio was fair, but car No. 4, which exhibited dazzling speed in the early stages of the race, went out in the 123d round with a broken connecting-rod. No. 21 (Wilcox) did not get into the money, and the only honors captured by the team was sixth place, which fell to No. 20, handled by Merz. Amplex No. 12, driven by Turner, made a creditable showing, finishing in seventh place. More was expected of Turner’s colleague, No. 44, than of the car that finished the race, because of the severe accident which nearly put Turner’s car out of the running during the practice. No. 44 turned over on the back stretch in the thirteenth round, after losing a loosened tire. This mishap resulted in the only fatality of the day, as Sam Dickson, mechanic, was crushed to death under the car. Greiner, the driver, suffered a broken shoulder and other contusions and bruises. Jackson car No. 25 (Cobe) made a splendid showing and finished well in hand in eighth place. The Knox entry was ninth and the small end of the purse went to Mercer 36 (Hughes). The New Jersey car ran smartly from end to end, but did not have quite enough power to land higher in the list. The Case trio demonstrated high speed and reliable going qualities, but all three developed trouble with the steering gear, so it was reported.

The Pope-Hartford pair failed to finish. Car No. 5 (Disbrow) lost ten laps through ignition trouble in the early stage of the race and was struck by Lozier No. 34 up the home stretch in the forty-ninth round. Both car No. 5 and No. 34 were put out of the running by this mishap. Car No. 6 broke a torsion tube in the last half of the race, but was repaired in time to have finished, had it not experienced some trouble with its gears while the relief driver was at the wheel.

The Buick pair did not get very far, dropping out after mechanical difficulties overwhelmed them. The Alco entry, winner of two Vanderbilt cups, negotiated a little over one-quarter of the distance and retired from the race with burnt-out bearings. The showing of the Jackson trio was satisfactory, despite the tremendous handicap under which they ran. On Sunday a gasoline fire in the garage in which these cars were stored almost destroyed them. The tires were burned off two of them and the insulation on one was badly melted. This probably caused the withdrawal of No. 24, from general debility, in the first quarter of the race. No. 26 also failed to get into the honorable list of finishers, but No. 25 won its spurs after having some mechanical trouble with its steering gear.

The toughest luck of the race fell to the lot of Marmon 31 (Dawson). This car certainly would have beaten the Mercedes giant and perhaps the Fiat 28 if the „jinx“ in the form of a broken radiator had not intervened in the final round. Dawson was obliged to stop his car up at the head of the stretch and watch the third and succeeding prize winners dash past him to victory. Not an atom of trouble had been experienced by the car from the start until the radiator sprung a leak.

The Apperson was doing nicely when it was put out by the Westcott in the sensational jam in front of the stand.

Simplex 38 (Beardsley) experienced clutch troubles and made the last few rounds in which it appeared with copper wire rather prominent in its mechanical parts.

The Velie, while never a factor in the race, performed creditably for a car of its size and power.

The showing of the Benz pair was very ordinary. Car 45 (Burman) went through a series of tire troubles that must have proved discouraging. The most spectacular event in which either of the Benz cars took part was when Burman, rounding the first turn, threw his right front shoe. The heavy casing and a metal rim whirled out on the track in front of the car, mounted the steep embankment at the south side of the speedway and, striking the 4½-foot retaining wall at the top of the bank, bounded high in the air and fell one hundred feet outside the course. Neither of these cars was in the first ten at the finish.

The cars in the field were not necessarily „stock cars.” The only qualifications required of them were that their pistons displaced less than 600 cubic inches and that they weighed more than 2300 pounds. Many of them measured the same as regular stock models put out by their manufacturers, but some were frankly and openly nothing more than special racing cars.

The winner is a peculiar looking automobile. Its lines are very slender. The hood covers an engine having six cylinders, 4½ x 5 inches and measuring 477 cubic inches. Its stern is drawn out to a long sharp point, extending back probably 4 feet from the driver’s cock-pit. There is room for only one person in the car, and to this fact possibly may be attributed its freedom from tire troubles and mechanical difficulties. The Lozier car is said to be identical with the 1912 model put out by that factory.

There were three elements of supreme importance in the winning of the race. It was a terrific test of man, mechanism and good luck. The timing device suffered its mishaps, too. About midway of the race the wire broke, but was repaired before the round was finished. Later, however, it snapped again under the continued pounding of the racing cars and was disabled for many laps. The scoring was only partially satisfactory, although there was an occasional variation between the boards. The officials had little to do after the racers had started. In preparing for the event a meeting of drivers and mechanics was held in Tomlinson Hall, which was attended by the whole force. Mayor Bookwalter addressed the drivers and cautioned them to obey the rules. Carl G. Fisher also made a brief address, and the officials of the meet instructed the crews as to their duties. To this fact may be attributed the comparative safety with which the race was run. It scarcely seemed possible to conduct such an event with such a field under such conditions without killing a dozen. The constant passage of forty racing cars around the course caused the first turn to be bathed in oil, and after 300 miles had been run the management caused the lower turn to be sprinkled with sand.

In the first hour the leading car traveled 721/2 miles. At the end of the second hour it had gone 150 miles; third hour, 222/2 miles; fourth hour, 295 miles; fifth hour, 370 miles; sixth hour, 445 miles. The winner’s time was 6 hours, 41 minutes and 8 seconds.

When Ray Harroun made his final dash, winning, and the race was declared closed, the excited throng were in a receptive mood, and the report was circulated of the death of S. P. Dickson, of Chicago, mechanic, who rode with Arthur Greiner, driver, of the Amplex „44.“ Eye-witnesses are authority for the statement that both rear tires burst at a curve, and Dickson was hurled a great distance against the fence, and from all accounts, his death was instantaneous. The driver, Greiner, had a narrow escape; the automobile was demolished. At the hospital it was learned that Greiner had a fracture of the arm and many contusions besides.

C. L. Anderson, mechanician, and Joe Jagersberger, driver of No. 8 (Case) stopped at the pit for repairs, and having com- pleted the task were getting away, but the spectators were in a position to observe that there was something wrong, and Anderson, as he bent forward in his investigation, fell out of the car; one of the members of the steering gear had been broken. The machines were passing with an interval of two seconds, and the spectators to the last man were given the shock of their lives, but Anderson got away.

Then came the Westcott thundering along at top speed with Harry Knight at the wheel and John Glover, mechanician, sitting tight. Knight saw Anderson in his path, and accordingly clapped on the emergency brake, resulting in strange pranks on the part of the machine; besides doing a waltz to rickety time it leaped up in the air and came down on its back. In the melee, while Herbert Lytle and two mechanicians were busying themselves on their Apperson car, the mad Westcott automobile grappled the Apperson and hurled it partly into the Benz pit, which was occupied by four men, but they escaped. Lytle and his mechanician were the most interested spectators for the moment, but beyond slight scratches, they too, got away. In the meantime, the Westcott car fetched up against a post and was wrecked.

Knight and Glover were hurled through the air for a distance of. 20 feet, and their present condition is best indicated in a special wire to THE AUTOMOBILE from the Methodist Episcopal Hospital at Indianapolis, as follows:

Indianapolis, May 31, 10:01 A. M. — Knight most seriously injured with a possible fracture of the skull, abrasions, and nervous shock. Glover has a strained back with slight possibilities of internal injuries. House doctor reports have neither of these patients on the danger list.

The other starters in the big race were: Case, driven by Lewis Strang, piston displacement, 284; Inter-State, C. B. Baldwin, 481; National, John Aitken, 589; Pope-Hartford, Louis Disbrow, 390 ; Pope-Hartford, Frank Fox, 390 ; Westcott, Harry Knight, 421 ; Case, Joe Jagersberger, 284; Case, Will Jones, 284; Stutz, Gil Anderson, 390; Buick, Arthur Chevrolet, 594; Buick, Charles Basle, 594; Fiat, Edw. Hearne, 487; Alco, Harry Grant, 580 ; National, Howard Wilcox, 589; McFarlan, Bert Adams, 377; Jackson, Fred Ellis, 355 ; Jackson, Jack Tower, 355; Cutting, Ernest Delaney, 390; Firestone-Columbus, Lee Frayer, 432; Marmon, Joe Dawson, 495; Lozier, Teddy Tetzlaff, 544; Apperson, Herbert Lytle, 546; Mercer, Charley Bigelow, 300; Simplex, Ralph Beardsley, 597; Fiat, Caleb Bragg, 487; Velie, Howard Hall, 334; Cole, Wm. Endicott, 471; Amplex, Walter Jones, 443; Benz, Robt. Burman, 520; Benz, Wm. Knipper, 444.

Timing of 500-Mile Sweepstakes May Be Mixed

Considerable doubt is being expressed among the automobile fraternity as to the accuracy of any times that may be given out as having been made at the 500-mile International Sweepstakes Race at Indianapolis. It is known that the wire from which the wheels of the racing cars sent the recording impulses to the automatic printing machine in the stand was broken at least twice during the course of the race.

During the periods when the machine was out of commission the work of timing and scoring the cars had to be based upon the timing officers‘ personal efforts. The first break occurred early in the race and the officials announced shortly afterward that it had been fixed and that only half a lap had been lost.

Later in the day, however, the continued impact of the racing machines caused the wire to break again and for an hour the timing had to be „done by hand.”

Thus it was necessary to supply by human means the service of an automatic machine at least twice during the race and for those two periods, naturally there is no tape from which to check the scores. The score by laps was a sort of symposium in which many willing hands and young heads had a part. For instance, during the greater part of an hour the Lozier car No. 33 was carried on the press board as one lap ahead of the winning Marmon, while the official slips showed that the Marmon was bowling along in front all that time. It was during at least a large part of this stage of the race that the automatic machine was out of commission. In explanation it was stated that the slips were correct and the board was at fault.

One of the representatives of The AUTOMOBILE called the attention of the officials to an error in the slips earlier in the race when these cards showed that Lozier car 34 was in third position at a time when the score board told of at least a dozen cars that were ahead of Tetzlaff’s. No. 34 was considerably behind ai the time noted and the officials made the correction.

Delay in Announcing the Result

INDIANAPOLIS, 5:50 P. M., May 31 — “Special Telegram to The AUTOMOBILE–Official score not yet computed.“

Delay after delay has been experienced in the issuing of the announcement of the official score of the 500-Mile Sweepstakes. Among the difficulties attending the digesting of the mass of figures involved, not the least is the failure of the electrical timing apparatus to maintain proper working order during the running off of the race. THE AUTOMOBILE gives here a half-tone reproduction of a piece of the „trip-wire,” showing how it parted during the race, thus placing out of commission the timing equipment, making it necessary to resort to personal methods of timing. It will be understood that the making up of the official score would be a relatively simple undertaking were it possible to rely upon the record. As the matter stands it is a serious question as to whether or not the official score will be out tonight; moreover, there is reason to doubt the accuracy of any score that may be patched up in view of the failure of the electrical timing apparatus at a critical moment. It is presumed that the „Contest Board“ will put its stamp of approval upon some sort of a score, but it will come too late to gain admittance to the columns of The AUTOMOBILE as it goes to press.

INDIANAPOLIS, 10:05 P. M., May 31-Special telegram to The AUTOMOBILE -Committee still deliberating. Pardington stated to the representative of The AUTOMOBILE that he hoped to be able to give out information about 9 o’clock. The wire went on to state: “Do not print results as at first given without another wire of confirmation—there does not seem to be any doubt about Harroun winning.

INDIANAPOLIS, IND., June 1, 1 A. M. (Special to THE AUTOMOBILE)—Dictaphones were in use to register the number of cars as they passed the judges‘ stand. An operator called the numbers to the members of the timing committee. The officials have just sent for these records and had to fetch the manager of the local branch of the Columbia Phonograph Company, Thomas Devine, to help them unravel the tangle into which affairs have been precipitated. No report on score tonight.

Photo captions.

Page 1230 – 1236

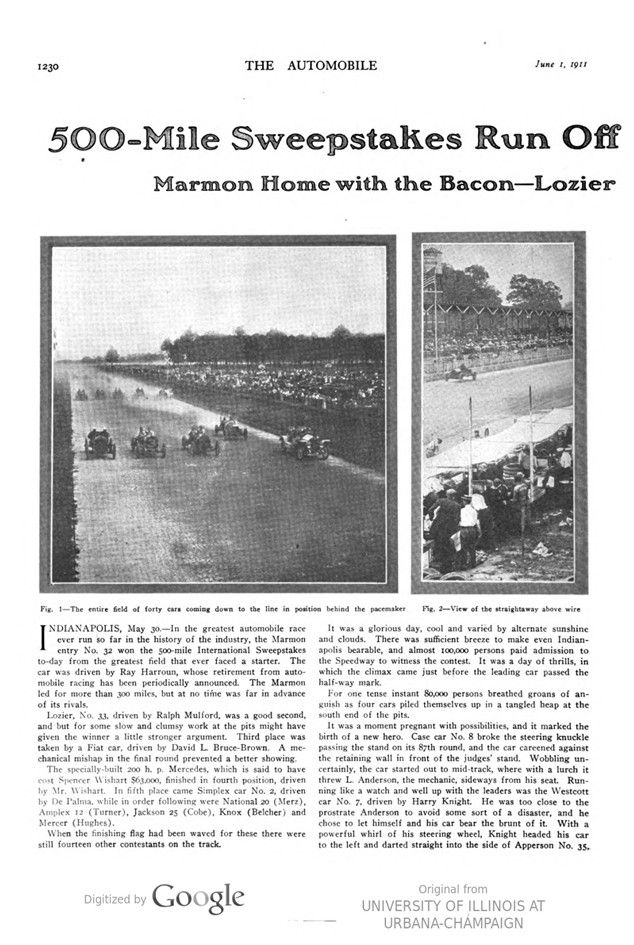

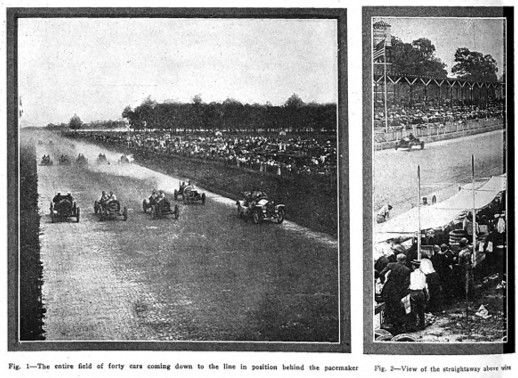

Fig. 1-The entire field of forty cars coming down to the line in position behind the pacemaker

Fig. 2-View of the straightaway above wire

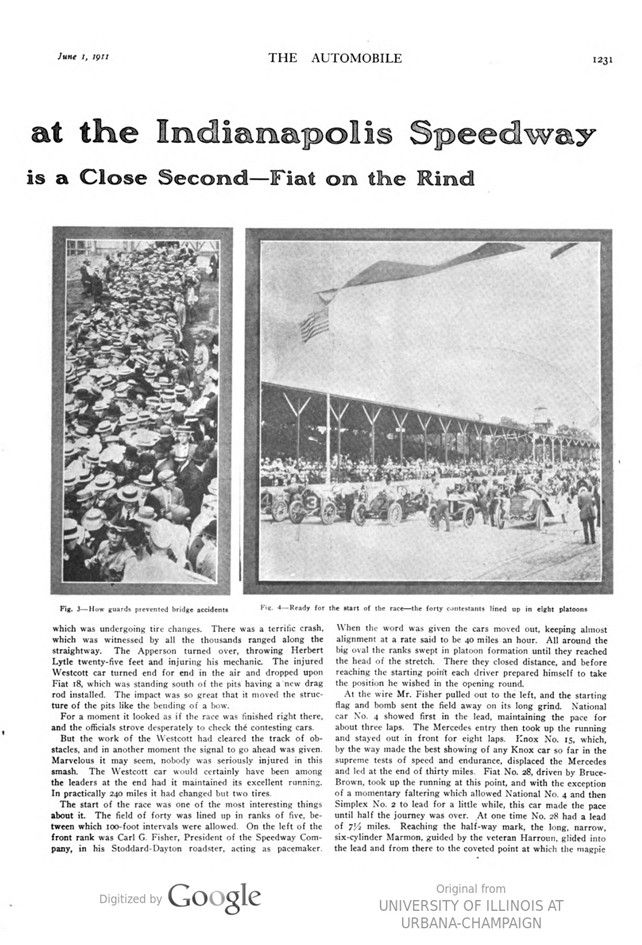

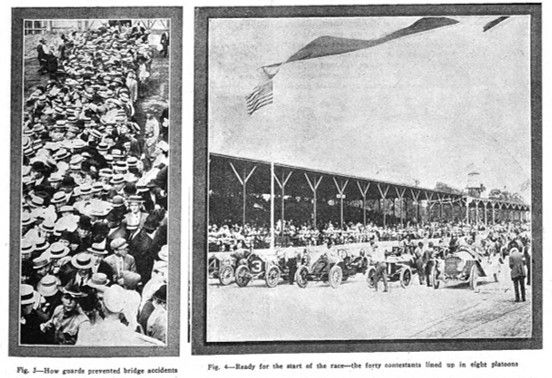

Fig. 3-How guards prevented bridge accidents

Fig. 4-Ready for the start of the race-the forty contestants lined up in eight platoons

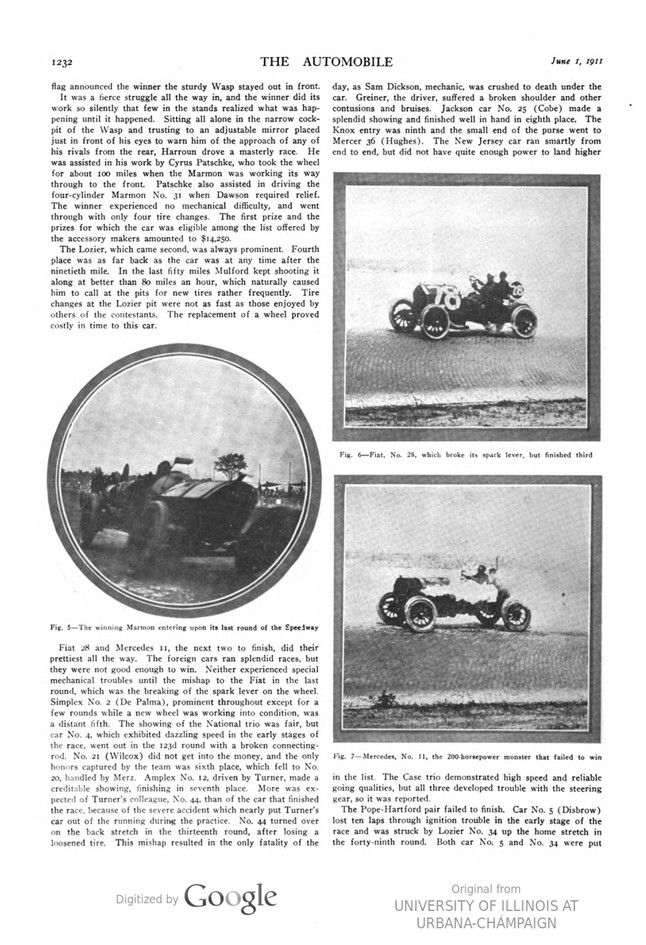

Fig. 5 The winning Marmon entering upon its last round of the Speedway

Fig. 6-Fiat, No. 28, which broke its spark lever, but finished third

Fig. 7-Mercedes, No. 11, the 200-horsepower monster that failed to win

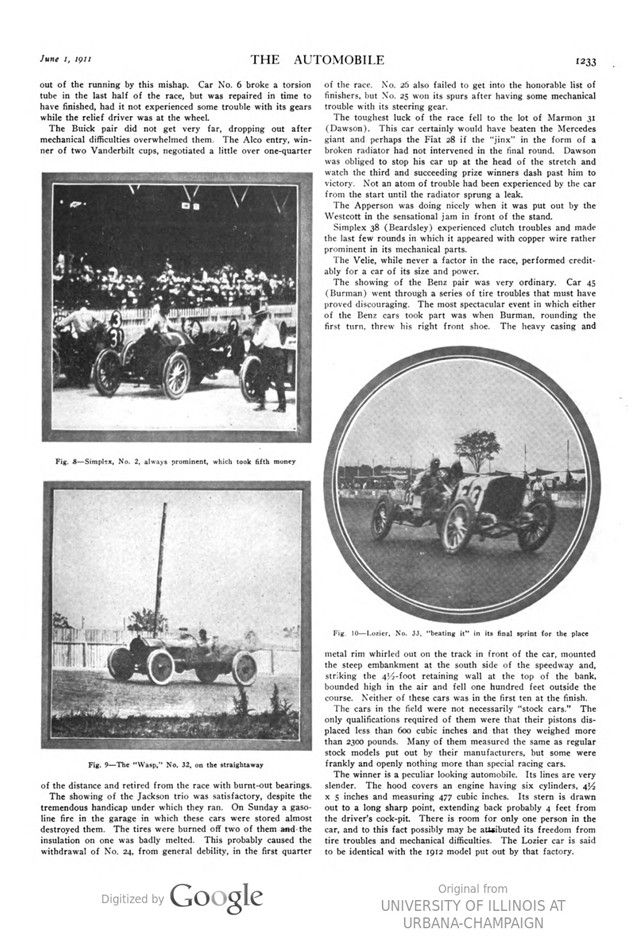

Fig. 8-Simplex, No. 2, always prominent, which took fifth money

Fig. 9-The „Wasp,“ No. 32, on the straightaway

Fig. 10-Lozier, No. 33, „beating it“ in its final sprint for the place

Fig. 11-Testing the gasoline for use in the race

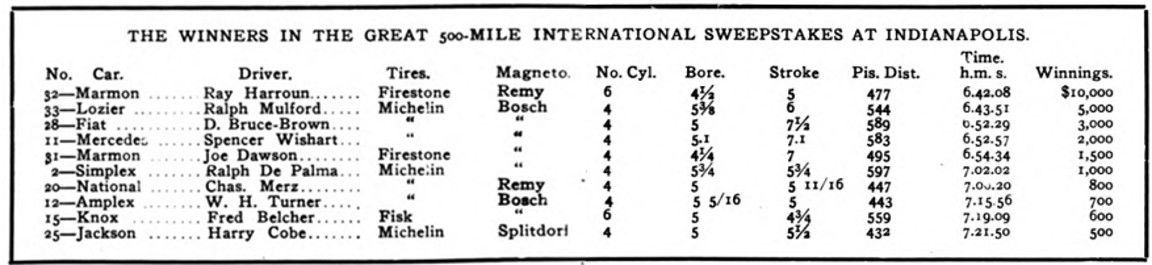

Fig. 12 Scene at the finish when the winning Marmon went under the wire

Fig. 13-The Jackson trio, including the car which captured eighth money

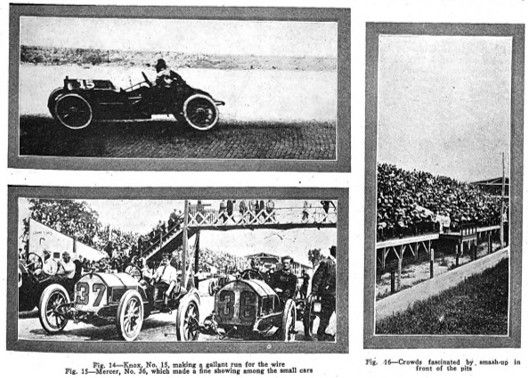

Fig. 14-Knox, No. 15, making a gallant run for the wire

Fig. 15-Mercer, No. 36, which made a fine showing among the small cars

Fig. 16-Crowds fascinated by smash-up in front of the pits

Fig. 17-Piece of the „trip-wire,“ showing how it broke during the race, putting the electrical timing apparatus out of commission for a time and interfering seriously with the accuracy of the automatic record