This Automobile Review report of the 1904 Gordon Bennett Race in Germany, is one of the many long and extended reports that were most normal for those days. Not only the race itself, but it was also common to give an impression of the route, explain cars and technical issues, as well as backgrounds. Have fun with this long read!

Text and photos with courtesy of hathitrust.org hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracingistory.com

Automobile Review, Vol. 10, No. 26, June 25, 1904

THERY, FOR FRANCE, WON GORDON-BENNETT

Germany Loses Cup–Thery, in 80 H.-P. Richard Brazier, Traveled 348 Miles in 350 min. 30 sec.

M. Thery, in his 80-h.p. Richard-Brasier, won the Gordon Bennett race on the Homburg circuit in Germany, and once again the coveted trophy is held by the automobile club of France. Thery swept everything before him in the French eliminating trials over the Ardennes circuit on May 20 and was picked by many as the man who would give Germany life-and-death race in their attempt to hold the prize, which Jenatzy, in his speedy Mercedes, won for them on the course in Ireland last year.

The four times around the circuit, a total of 348 miles, was covered by the Frenchman in 5 hours, 50 minutes and 3 seconds, or in round numbers, 350 minutes. This wonderful performance of a mile-a-minute for nearly 350 miles, over treacherous roads, marks a new era in motor racing and sets a high standard for the international cup entrants. Jenatzy, who was second in the contest, required 6 hours, 1 minute and 21 seconds, or 11 minutes 18 seconds longer than Thery. This loss was owing to improper arrangements for taking on fuel at the different controls, which resulted in Jenatzy’s running short on one occasion. The contestant to make the third best time was the German, Baron de Caters, on his powerful Mercedes car, who made the four circuits in 6 hours, 46 minutes and 31 seconds. Of the other fifteen cars that started, Edge, the pride of Great Britain, and who made wonderful time in the British eliminating trials, was forced to abandon the race because of tire troubles. Girling and Jarrott, the other British entrants, with Wolseley racers, had numerous troubles, and the former required seven hours to complete the distance. Fritz, Opel, of Germany, with his Opel-Darracq car, ran in hard luck, first a spring gave trouble and finally a broken shaft retired him from the contest.

Lancia, of Italy, with his Fiat car, collided with the Belgium machine, driven by Augieres, and both were eliminated. Storero, one of the other Italian contestants, broke an axle on his Fiat racer and withdrew.

The remaining eight encountered no serious difficulties during the race. Jenatzy narrowly escaped colliding with a locomotive that stood directly across the course. He was making a mile-a-minute clip over one of the fastest stretches when the wild shouts of some spectators made him slacken somewhat, after which he slowed down and lost only a minute or so.

The policing arrangements throughout were. superb, the roadway excellent and the day as bright and warm as could be desired. The crowds that flooded the grandstands on either sides of the course at the Saalburg were representative of the different competing nations, and while the tribunes were not packed, the attendance was far in advance of that at any of the four previous events. The Ge man Emperor and Empress arrived early, did Prince Henry, all of whom watched the contest from start to finish and evidenced great interest in all the cars, but chiefly in that of Jenatzy, who is the idol of Germany in the automobile racing field. The Royal stand was filled with many titled personages from the six contesting nations, conspicuous among which were the French and English visitors who attended the „Motoring Derby‘ in great numbers.

Waiting the Start.

Saalburg was awake early and scarcely had old Sol sent his first rosy herald across the morning sky than natives and visitors were astir getting ready for the greatest automobile event in history. The morning broke beautiful and clear and on the day was a perfect fulfillment of the brilliant dawn. Every road leading to the starting point was alive before 6 o’clock, and long before seven, the hour of the start, the grandstands were full, the course was lined with spectators, and the racers were ready. It is estimated that over 1,000 cars passed along some of the leading routes to the Saalburg, and horse vehicles were numerous. Emperor William. and the Empress arrived a few minutes before 7 o’clock and took their place in the Royal box. The Emperor was dressed in the uniform of the Horse Guards and until the warning bugle rang out occupied himself by laughing and talking with his party.

The vast concourse was hand early and the two immense grand stands that faced each other on opposite sides of the course were filled. The scene was one never to be forgotten by those who attended. The huge tribunes with the track between suggested the tournament lists of the days of chivalry. Instead of the bounding steeds and armored knights, were the racing monsters and their grim operators. From above the seas of faces looked upon the different competitors as they entered the list at one end and shot out at the opposite on their 348 mile race. Later, when the machines had all disappeared, the attendants chatted together, compared watches, wondered how the racers were progressing and anxiously awaited the bugle that heralded the approach of each rider, as he completed his first, second, third and fourth circuit. As the drivers swept past on their respective laps, they were given ear split- ting ovations by the different nations they represented.

The Start.

Jenatzy, the hero of the 1903 Gordon Bennett, was first to start, and as the bugle at the farther end of the great arena heralded his start the whole assemblage rose as one mass and cheered the “pride of Germany“ as he shot between the walls of humanity. German enthusiasm lost all bounds and every voice shouted and every heart pulsated with pride and expectancy. As he flashed past the Emperor’s box at top speed he saluted his Majesty and then a thunderous shout, from every throat, filled all the air and in a second more the first Gordon Bennett competitor was speeding far away on his long journey.

The mighty shout nerved the hearts of the other seventeen who waited anxiously for the thrilling bugle to summon them to the starting post.

S. F. Edge, the “hope of Great Britain“ in the race, was second to start. For several minutes previous he and his mechanician were quietly but alertly waiting their call. Suddenly and clarion like the warning bugle sounded and bullet-like the great British driver shot out between the walls of excited spectators. His departure was well punctuated by continuous rolls of cheers from his admiring countrymen who looked to him to once again restore the cup to British soil. His start was considerably better than Jenatzy’s, and the fact gave some of the Island visitors chance to excel in exuberance the lusty sons of the Fatherland.

The third starter was Warden, the only American driver who drove one of the yellow and black Mercedes cars that represented Austria. His start was good and throughout the four circuits his performance was noticeable for careful and consistent driving.

Cagno, the Italian, was fourth man off, and after him Thery, the „boast of the French,“ in his 80 h. p. Richard-Brasier car, was started. His warning bugle electrified the French who, perhaps had a few memories of German victories in 1870 in their minds, and who had come to see the great Jenatzy eclipsed if possible. They trusted firmly in the daring, adventurous Thery, and the conclusion showed that their trust had not been misplaced. His departure was sensational, for scarcely had the bugle ceased than arrow-like he flew past in his blue racer. The French cheered, hats were tossed high in the air, women overflowing with enthusiasm waved handkerchiefs and parasols, and the shouts of „Vive la France“ were heard above the great din. Before the clamor ceased Thery had almost disappeared. Ears and eyes were expectant for the next call, and the next racer. Of the remaining fourteen, Baron De Caters (German) was delayed for some fifteen or sixteen minutes. His motor was running excellently until a few seconds before the start when it suddenly stalled. The trouble was with an oily ignition point, a trouble that frequently arises in big cars. His start was quite thrilling, in that he was only a few yards behind Herr Braun, the German driver for the Austrian team. The two raced side by side, and when De Caters could be seen pulling ahead of the Austrian car his friends gained heart again.

Mr. Jarrot, of the British team, had a good start and the three Italian Fiat cars. went off beautifully. Fritz Opel, the third German driver, who was thirteenth to start, left amid a cloud of smoke and incessant volleys of reports. It was the last chance for the Germans to cheer a starter and they spared neither throats nor lungs in the thrilling shout that marked Opel’s departure.

Salleron and Rougier, for the French, and Baron de Crawhez, Augieres and Hautvast for Belgium, were heartily cheered. Werner, a German, who drove the third Austrian car, was loudly cheered.

The Race.

The race throughout was a gladiatorial contest between the fearless Jenatzy, with his German Mercedes car, who was looked upon by his countrymen as the „first racer in Europe,“ and the invincible Thery, whose Richard-Brasier car was to restore the cup to the French club. Every mile of the course was fiercely contested and had not the German had trouble at some of the controls with the gasoline supply the eleven minutes margin belonging to Thery would have been clipped down to a minimum.

Baron De Caters, of the German team, was the third to complete the course, but his time was almost three quarters of an hour longer than that of Jenatzy and nearly an hour more than Thery’s. The others required from that until over seven hours to make the four circuits.

Never in a motoring race was excitement so high as when Thery and Jenatzy fought and struggled for the prize.

Jenatzy’s start was not nearly so good as Thery’s, but during the 85 miles of the first circuit there was ample time for making up any losses. After the last contestant was off the crowds grew anxious for the first one to repass the stand. With the Germans it was Jenatzy and every ear was ready for the thrilling bugle to announce his approach. Expectancy gave place to uneasiness, that was in turn almost supplanted by anguish as the breathless crowds waited. At last the bugle sounded, Jenatzy was coming, and the crowds were on their feet. A moment later and the German flew past, accompanied by a whirl of dust, a roar from the car and deafening plaudits from his countrymen and the visitors.

Thery’s approach was heralded, and as he dashed be- tween the stands „Bravo Thery,“ „Vive la France,“ rent the air and drowned the applause of all the others. He was driving beautifully, his car as it flashed past seemed a per- ‚fect running giant, and Thery, with all the nerve of an adept, was forging her along at a break-neck rate. How- ever, he was 31 seconds behind Jenatzy on the first lap and the information was sufficient to turn the German section into absolute pandemonium. They were winning, the re- doubtable „Red Devil“ was dividing the space between him and the Hounding Thery and their joy was to the full.

While they waited the other contestants passed, and were cheered, but the race was between Thery and Jenatzy, and the crowd knew it. Thery had made his circuit in 1 hour, 27 minutes and 27 seconds. Jenatzy had needed but 1 hour, 26 minutes and 56 seconds.

When they passed the grandstands on the second lap Thery was one minute and 40 seconds in the lead, having gained 2 minutes and 11 seconds, and his car was running well. The excitement grew intense, spectators were fevered into excitement as to the outcome. France sniffed victory for the first time and the Germans had a forecast of the end. The third circuit was as hotly contested as the two previous ones, but it was during this lap that Jenatzy had trouble getting gasoline at one control and fully eight min- utes were lost. They dashed past the stand for a third time and sped forth on the last circuit. Spectators realized that Thery was increasing his lead, but were not aware that he was nine minutes and 35 seconds ahead. However, it was the Frenchmen’s chance and if they had won back the provinces lost during the Franco-German war they could have not been more hilarious. For several minutes after Thery had disappeared the bedlam lasted and then they settled down for the grand finale. They anxiously waited for the Jenatzy bugle at the finish. Thery was ahead and leading by nine and a half minutes; it was impossible for the Ger- man to catch up unless some accident happened. Was the cup once more within their grasp or at the last moment was a sudden jolt, a burst tire or something else going to place it beyond their grasp?

If Thery’s good luck continued the race was his, his fingers were gradually closing round the trophy and every French heart beat anxiously for the finish. It was anguish to all as they looked at the Emperor’s box, looked towards the bugler and then looked down the course. Hours were stretching themselves into weeks, perspiration was forming on many a brow; eyes and ears were strained, but still no Jenatzy bugle sounded. They waited, and they watched; the suspense was intense; the Emperor gazed down the course and so did the others.

Jenatzy’s time was almost up, an hour and twenty-six minutes had passed since he left on the final lap. Another minute slowly died away, then another, and in a few seconds the bugle blew, it was Jenatzy’s warning and the crowd were on their feet. He was madly cheered as he dashed over the finishing line, but the spectators knew that he had started on the race 28 minutes ahead of Thery and they were doubtful as to how many minutes remained before Thery must arrive if he was to lift the cup. Soon it became ‚known that they had 19 minutes grace, and if he crossed the line before that time the cup was his. The last agonies were worse than the first. On every French face was stamped pronounced uncertainty. Was his good car going to come in ahead, as it did on the Ardennes circuit? Was Thery’s nerve as good as then, and were the fates with him? These and countless other thoughts perplexed the French, while gloom rested on many a German’s brow. Minutes passed slowly, one, two, three, four, and five were gone, and the watches ticked slower and slower. Necks were strained and eyes cleared; but still no Thery trumpet call. Six, seven, and eight minutes passed, but not a stir, the suspense was becoming maddening; nine and ten were ticked off and eleven was gone, when suddenly the shrill notes were heard. It was Thery’s warning; he had won the day and was dashing towards the finishing line. There was a ripple of excitement throughout the stands, a general rising, and then when the victor was seen a great shout that rent the district rose. As he shot across the line, more like a projectile from a cannon’s mouth, the French became delirious with joy, the stands were a mass of waving handkerchiefs and hands and the air was filled with shouts. Thery had won by a margin of 11 minutes and 18 seconds. France had conquered Germany on the motor field and her people were glad. The Emperor, in good sport, waved his hat to the winner, the French shouted uproariously, the English joined the tumult, and for several minutes the din was tremendous. Thery had occupied but 1 hour, 26 minutes and 23 seconds on the last lap, while Jenatzy had consumed 1 hour, 28 minutes and 13 seconds.

After Thery had crossed the finishing line he wheeled round and went back to the stand. He was the uncrowned monarch of the motor world, and all nations there represented greeted him as such. He smiled to his admirers, doffed his cap and appeared as cool and unfatigued as if he had just completed a trial spin. His faithful car bore no marks of the tremendous pace beyond a goodly coating of dust, and the tires appeared to have stood the enormous strain perfectly.

His time for the different circuits was as follows:

Hrs. Min. Sec.

First 1 27 27

Second 1 16 22

Third 1 29 51

Fourth 1 26 23

When interviewed immediately after the finish he said: „I am delighted with the way the race has been run. I think it remarkable from the point of view of sport. The arrangements for the course were remarkable as a specimen of perfect organization.

„As for the race itself, there is nothing to tell. I had not the slightest trouble with the machine from the moment the signal was given me to go until the moment I finished. I had no mishaps, no ‚pannes,‘ not even a punctured tire. The machine ran wonderfully smoothly, as you may see from the time of my rounds.“

Jenatzy Vanquished.

Jenatzy, the German hero, was vanquished, the Fatherland had lost the cup, but the effort made was a noble one and the Mercedes machine behaved admirably. The crowds realized the splendid race he had put up and cheered him to the echo after the contest was over. His time for the different circuits was:

Hrs. Min. Sec.

First 1 26 56

Second 1 28 33

Third 1 37 46

Fourth 1 28 13

The Richard-Brasier Car.

The 80-h.p. car with which the race was won, is of the four-cylinder vertical, water-cooled type. The valves are mechanically operated, and magneto ignition is used. The front of the square shaped hood is formed by the combined tank and radiator and a fan for extra cooling purposes is employed. A strong sliding gear transmission is used which gives three speeds and a reverse, with direct drive on the high speed. The wheelbase is 84 inches and the tread standard. The drive from the counter shaft to the rear wheels is through two heavy chains.

A feature of this car is that it is one of the low powered cars and competed successfully against 90 and 100 h. p. machines. It has small weight per horse power, and its strong point is its motor. When running at any speed the mixture is automatically controlled and the cylinders never overheat. The steering rods are in front of the front axle. The car in outward design is not dangerously racing-like, as the large oblong bonnet and rectangular radiator makes it more humane in appearance. The driver sits well over the rear axle in a comfortable nest-like place. The steering column inclines well to the rear and the operating levers are close at hand. A feature of this car as a racer is the use of long sloping mud or dust guards for the front wheel which have a great effect in keeping road particles, torn up by the front wheels, from flying in the driver’s face.

Richard-Brasier Anti-Bounce Device.

The Richard-Brasier car that Thery rode in the big event was fitted with an anti-vibration device that doubtlessly contributed its share in the victory. This device, known as the Trauffault suspension, designed to suppress the „bouncing“ action of the machine when at high speed, so that the driving wheels do not leave the ground to the same extent as with ordinary springs, thereby obviating more or less lost power.

The effect of the shock absorber is similar to a boat running on even keel in smooth water as compared with an unevenly ballasted craft in lumpy water. Two of them are necessary, one on each end of the rear axle. They can be fitted to either chain driven or live axle cars.

On a rough road a car to which this system of suspension is applied does not receive a succession of shocks when negotiating a large obstacle or a sudden rise or fall on the road surface. The occupants of the car, therefore, scarcely feel any vibration, it having been absorbed by the device. Anyone who has driven an automobile at high speed will realize the benefit of such a device.

The Winner.

Fearless and audacious Thery is not a novice in the automobile field, but has been at the wheel through varying vicissitudes for eight years. His steady nerve and good judgment cannot be overestimated. He takes curves on the high speed that others have difficulty with on the intermediate and he seems to be a perfect thermometer of the powers and possibilities of the car he drives.

He made his debut in the racing field in 1898 in the race from Paris to Amsterdam, on a Decauville voiturette. In 1899 he completed in the Tour de France and classed second to Gabriel in the voiturette class. In the criterium for voiturettes, which was won by Cottereau in the same year, he was also second.

In 1900 Thery won the cup for voiturettes on the road from Bordeaux to Perigueux, and in 1901 he was fifth in the light car class in the Paris-Bordeaux race. Just before the Paris-Berlin contest he was taken ill and could not compete.

In 1902 he took part in the Paris-Vienna race, had a bad accident in coming down the Arlberg, and repaired his car in a marvelous manner in a single day and finished the race. Toward the end of the same season, he won the hill climbing trial at Gaillon and broke the kilometer record for light cars, being the first to do a speed of 120 kilometers (about 74 miles) an hour.

In the Paris-Madrid race, last year, he was fourth in the light car class. In telling the story of the Paris-Madrid race, Thery says that when he had passed Marcel Renault’s broken car, and then, further on, when he saw the accident that occurred to Lorraine Barrows, it made such an impression on him that he felt he could not put on speed any longer, and he finished the race at a speed of 60 kilometers (37 miles) an hour.

Thery is a robust, good-natured fellow, is an excellent mechanician, and knows his car thoroughly.

The Donor.

James Gordon Bennett, proprietor of the New York Herald, lives in Paris most of his time. He was born in 1841, being now 63 years old. He has controlled the New York Herald since the death of his father. It was in 1893 and ’94 that he foresaw the usefulness of the motor car for pleasure and commerce and since then has probably done more for the industry indirectly, than any other in the world. He is a great enthusiast in yachting and is rarely more delighted than when driving a four-in-hand along the boulevards of Paris.

The Gordon Bennett trophy was donated by him and contested for the first time in 1900, when it was won for France by Charron on a Panhard car.

It is interesting that two great enterprises are connected with James Gordon Bennett and the New York Herald. Stanley was commissioned to darkest Africa, and the Gordon Bennett trophy was bestowed. Both of these events have done wonders in their lines and will ever keep the name of Gordon Bennett, and the New York Herald before the civilized world.

Belgian Cars.

Belgium was represented by three powerful Pipe cars, with 90 h. p., vertical four-cylinder motors, cast in pairs. The armored wood frame projects well to the front and the motor is carried some distance behind the front axle. A feature with them is the magnetic clutch that was invented by Jenatzy, and the drive between the clutch and rear wheels is through bevel gears and side Chains. Large mechanical valves are used throughout and high-tension ignition, with accumulators. is made use of. The radiator is placed low in front so as to allow for the sloping boat-like hood. The carburetter is self-governing and operates under pressure from the fuel tank. The sliding gear transmission which is operated by a lever at the right of the steering wheel, gives four forward speeds and one reverse. The drive on the top speed is direct. Four brakes are used, two being on the differential countershaft and two on the rear hubs. The artillery wood wheels are fitted with Continental tires. All mechanical parts are well housed by a continuous drip pan, and from a passing glance you would imagine them to be excellent atmosphere dividers. They have a long wheelbase and standard tread and are similar to the regular Pipe stock cars.

Italian Fiat Cars.

The three black racers from the Fiat factories that represented Italy are all rated at 70 h. p. As racing cars, they are quite normal in appearance and not so rakish‘ and monster-like as several of the other contesting types. They have a wheelbase of 110 inches, 53-inch tread and were shod with 342-inch tires. The pressed steel frame projects some distance forward in front of the bonnet, resembling to a degree the Mercedes design. The engine and honeycomb radiator are some distance in rear of the front axle, allowing the rear wheels to take their share of the load. On the four-cylinder vertical engines, magneto ignition is used, and the float feed carburetter is fed under pressure from the gasoline tank, located in the rear of the car. The valves are mechanically operated, and the drive is by two heavy side chains from the differential countershaft to the rear wheels. The sliding gear transmission gives four speeds forward and a reverse and has direct drive on the high speed. The speeds are easily controlled, and the gears are exceptionally heavy, so as to admit of changing at any time and under any speed without danger of stripping. A novelty in connection with the fly wheel is that it forms a fan and sends a current of air against the radiator. The steering column inclines well toward the rear, and the operating levers are placed well to the front at the operator’s right. The machinery is well closed in beneath by a covered oil pan.

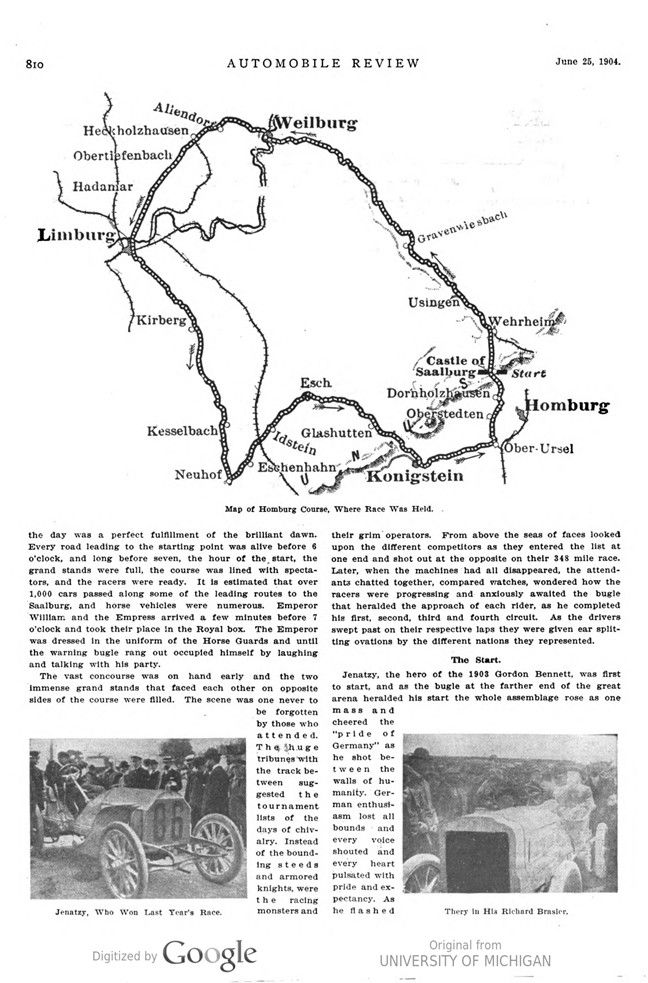

The Gordon Bennett Course.

The course is situated in the midst of the Taunus mountains, near Homburg, the distance for the circuit being 85 miles. The Saalburg, which was at one time a Roman fortress, was the starting point for the race. The course takes a northerly direction to Usingen, starting with a short rise for about 300 yards, followed by a drop of 114 miles to the village of Wehrheim, before entering which the railway is crossed. The road after leaving the village rises slightly for a distance and is followed by a long descent into the town of Usingen. This was one of the neutral points on the course and included the second dangerous curve. The road is uphill again after leaving this place, and another 2½ miles further on brings the down grade into Gravenwiesbach, and the road is of rather a winding nature. The curve immediately before entering the village is one where many accidents have taken place, both to motor cars and cyclists. Continuing through the village in a fairly straight line, the road is of switchback description as far as Weilburg, passing through wooded country. Just before reaching this village a short but very steep descent is encountered with a dangerous S curve, and another nasty corner is met with just before entering the village itself.

The road after leaving here passes over the river and continues for 2½ miles up some steep and difficult hills, but after surmounting these falls gradually until nearing the village of Allendorf, when a very steep and dangerous descent occurs. After leaving this place the road is on a downward grade all the way to the village of Heckholzhan, on entering which the usual nasty corner has to be turned. From here the road onward to Limburg is of an easy class.

Leaving Limburg, the course is slightly uphill and becomes of a switchback nature through Kirberg. On leaving this place uphill work is again tackled, and reaching the crest the road enters the woods, still mounting slightly, but afterwards with a gradual descent to Hunerkirche. From this place to the next village (Neuhof) the road winds through woods, a sharp drop of about % of a mile ending with a very bad turn to the left for the town, and then continuing uphill in a northerly direction. Another sharp drop Is encountered before entering Eschenhahn, as also a nasty S curve at the entrance to Idstein.

Leaving here, there is a long 2 miles followed by a sharp descent into Esch, just before entering where one of the most dangerous curves on the course is met with. Leaving here, a very stiff hill is ascended. It is about 1 mile long and absolutely unrideable for cyclists. After surmounting this the road becomes fairly level, rising again and then on for another seven-eighths of a mile, when we have arrived at the topmost point of the course (2,280 feet above sea level).

The road now commences to fall gradually, with here and there dangerously sharp drops and S curves, some of the gradients being as steep as 1 in 5. The road takes a sharp turn into Konigstein — a town of about 2,500 inhabitants. Leaving Konigstein, the road bears left on a falling gradient for about 2 miles, when wooded country is again entered, the road becoming of a switchback character, ending with a sharp turn into Oberursel. From here onwards the road is very good to Oberstaten and through Dornholzhausen, which is only 3/4 of a mile from Homburg. On leaving Dornhalzhausen the ascent of the mountain is begun, the road winding gradually upwards on an average grade of 1 in 40, and after about 2½ miles traveling the circuit is complete.

How the Race Was Won Last Year.

In 1902, Edge, the best driver in Great Britain, was the winner, and so it was up to the Automobile Club of Great Britain and Ireland to secure a suitable course. After much difficulty this was secured in Ireland where a 368½ mile circuit, excellently adapted for a good race was sanctioned. The race was a walk over for the German Mercedes car, driven by Jenatzy, and so the cup passed to Germany. In the event five finished, the order being Jenatzy (Germany), first; Knyff (France), second; Farman (France), third; Gabriel (France), fourth, and Edge (Great Britain), fifth.

In the race America was represented by Alexander Winton (Winton), Percy Owen (Winton) and L. P. Mooers (Peerless), none of whom finished the race. Jenatzy’s time for the 368½ miles was 6 hours and 36 minutes.

The Grandest Race Ever Held.

The Germans, though losers, this year, are outspoken in declaring that the 1904 contest was the finest event ever seen in Germany. In speaking of the event an authority on motoring stated: “There may be various opinions as to the result from the point of view of force, or even as regards automobile racing in general, but everyone must admire the courage and presence of mind and skill of all the men who took part in the great contest. It may be that one or the other received the promise of a splendid material reward, but at the start everyone must have felt that he was staking his life on the race.

“There must be wonderful charm in this racing for life or death, this reckless pursuit of glory, the charm of which only the strong nature of men of iron can bear to enjoy.

May Be the Last Gordon-Bennett.

„It is believed in automobile circles that this is the last race for the cup. The enormous expenditure it entails and the difficulty of finding a suitable course justifies the belief that people will hesitate to run the race in the future. However this may be, if the international cup race of 1904 is the last of its kind or not the grandiose struggle which took place in Germany will be for everyone who witnessed it an unforgettable spectacle.“

Salleron’s Bad Luck.

Fates were against M. Salleron who rode a Mors car in the French team. His own words are:

“I had no luck during the race. My first delay of over half an hour, was caused by the necessity of changing a chain. At Weilburg I noticed that one link was worn and decided to change right away rather than risk a bad accident. I should like to make clear that the chain was not made by Mors. The motor ran splendidly throughout and never showed signs of stopping. There was no mis-firing. I lost ten minutes later on by getting a nail in my back tire. I think the race was a good one, but over the most dangerous course I have ever seen.“

Thery’s Time.

Thery’s average time for the 348 miles was 59 2-3 miles per hour, or almost a mile a minute. His fastest speed was on a smooth stretch near Wehrheim where he traveled 91 miles an hour.

Hot in Controls.

Drivers, as well as spectators, asserted that during the race it was very hot in the controls.

“While going,“. Thery said, „I was quite comfortable, but in the neutralized portions the heat was terrific.“

The Gasoline Trouble.

The German staff for supplying gasoline to their drivers were very faulty at the several controls. It was badly stationed and not half large enough. As a result, Jenatzy ran short of fuel on the third round. Fortunately for himself he had a small can with him, but several minutes were lost in filling and re-starting. The flow of gasoline on the Mercedes automobile is worked by pressure as the tank is low down, As soon as the stopper is un- screwed the pressure goes and several minutes‘ pumping are necessary before the flow recommences. For touring purposes, the principle is excellent, but racing is a different matter.

Baron De Caters, the other German entrant, who came in third was delayed 35 minutes at Limburg, owing to poor facilities for providing gasoline.

Notes.

The Richard-Brasier car is a fine production. Its smooth running before the race made many feel that Germany’s chances of keeping the cup were not particularly bright. The regularity and smoothness of the march of the Richard- Brasier cup contestant have never been equaled in the history of motoring.

The mechanician on Thery’s car said: „I believe the machine could have covered twice the distance and been found to be running as well at the end of it. The motor was comparatively cool, and the tires hardly touched.”

Over this difficult course M. Thery’s performance was repetition of the eliminating race in the Ardennes, and the result is one more solid proof that exaggerated powers are worth little in comparison with moderate ones for long distance racing.

The start in the morning was uneventful save for Baron de Caters‘ bad luck. He had a good Mercedes without doubt, and his motor was running well until a few seconds of the signal. The ignition point became oily and nearly a quarter of an hour was lost. Once started, Baron de Caters went well and he had no recurrence of any serious mishap. The race that M. Thery won does not eclipse M. Jenatzy’s splendid struggle his Mercedes. This machine smoothly from start to finish. The tires, however, suffered somewhat, and the canvas was exposed on the left front, which was probably the result of applying the brakes when traveling fast.

The Wolseley automobiles held out much better than was anticipated and Girling had reason to congratulate himself on finishing in a little more than seven hours.

M. Opel, with an Opel-Darracg, had not been en route many minutes when he broke the front spring. It was due to a shock in passing over a level crossing.

M. Brasier, the designer and manufacturer of the winning car, was delighted for himself and the whole French industry that the cup was once more in France. He was not surprised at the result.

„I have worked for it“ he said, „and felt sure that if no accident happened, they must make a good show. I am delighted and say no more.“

Foto captions. pages 13-20.

Thery, Winner of 1904 Gordon Bennett. – James Gordon Bennett, Donor of Trophy.

Map of Homburg Course, Where Race Was Held.

Aliendorf – Weilburg – Hedholzhausen – Obertiefenbach Hadantar – Limburg – Gravenwiesbach – Usingen – Kirberg – Wehrheim – Start – Esch – Castle of Saalburg – Dornholzhausen – Oberstedten- Homburg – Kesselbach – Idstein – Glashutten – Ober-Ursel – Eschenbahn – Neuhof – Konigstein.

Jenatzy, Who Won Last Year’s Race. – Thery in His Richard Brasier.

Salleron in His Mors French Racer – Fritz Opel (Germany) in Opel-Darracq Car. – Between Obertiefenbach and Limburg.

Start at Saalburg. – A Good Road. – Turn Near Oberstedten – Rougier (France) in Trucat Mery. – Charles Jarrott (England) and His 96 H. P. Wolseley.

The Grand Stand at the Starting Point. – Hautvast (Belgium) with Pipe Car. – Entering Wielburg. – Approaching Esch. – Between Saalburg and Wielburg. – Near Neuhof.

Ten Per Cent Hill in Weilburg, – Cathedral in Limburg. – Just After the Start. – Cagno in His Italian Fiat Racer.

Girling (England) with 72 H. P. Wolseley. – How the Roadbed was Prepared. – West of Weilburg. – Corner Between Esch and Konigstein. – Konigstein.

Gates at Saalbury. – Weilburg. – In Konigstein. – A Bad Turn. – Idstein.