Text and photos with courtesy of hathitrust hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracingistory.com.

CYCLE AND AUTOMOBILE TRADE JOURNAL – Vol. 8, No. 1, August 1, 1903

The Gordon-Bennett Race

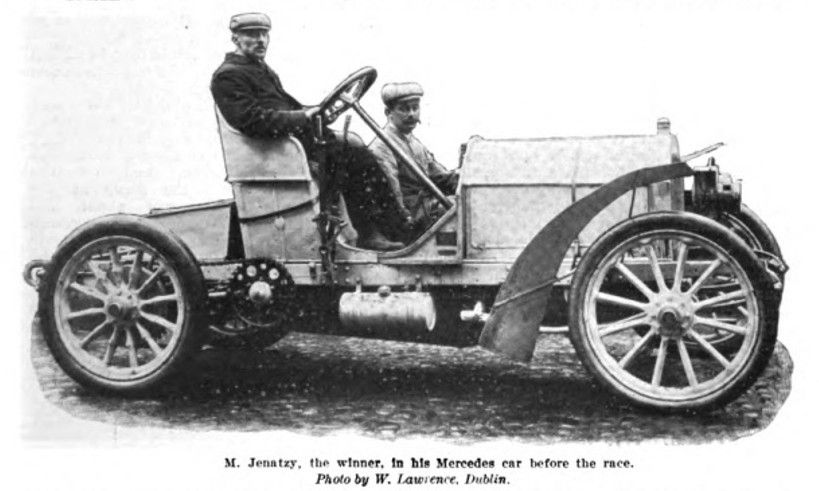

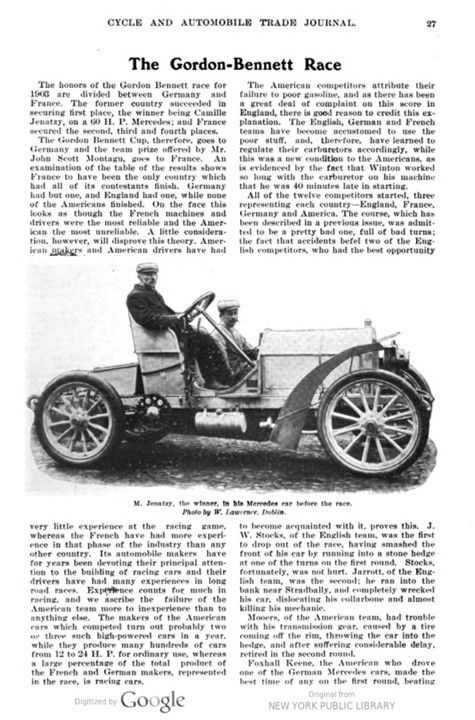

The honors of the Gordon Bennett race for 1903 are divided between Germany and France. The former country succeeded in securing first place, the winner being Camille Jenatzy, on a 60 H. P. Mercedes; and France secured the second, third and fourth places.

The Gordon Bennett Cup, therefore, goes to Germany and the team prize offered by Mr. John Scott Montagu, goes to France. An examination of the table of the results shows France to have been the only country which had all of its contestants finish. Germany had but one, and England had one, while none of the Americans finished. On the face this looks as though the French machines and drivers were the most reliable and the American the most unreliable. A little consideration, however, will disprove this theory. American makers and American drivers have had very little experience at the racing game, whereas the French have had more experience in that phase of the industry than any other country. Its automobile makers have for years been devoting their principal attention to the building of racing cars and their drivers have had many experiences in long road races. Experience counts for much in racing, and we ascribe the failure of the American team more to inexperience than to anything else. The makers of the American cars which competed turn out probably two or three such high-powered cars in a year, while they produce many hundreds of cars from 12 to 24 H. P. for ordinary use, whereas a large percentage of the total product of the French and German makers, represented in the race, is racing cars.

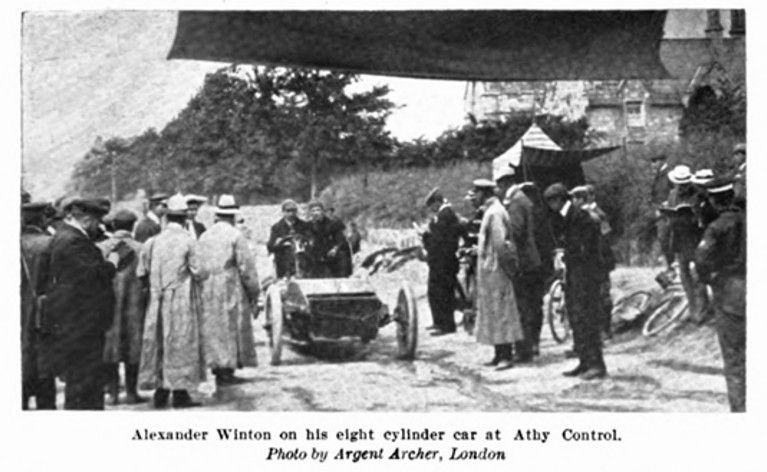

The American competitors attribute their failure to poor gasoline, and as there has been a great deal of complaint on this score in England, there is good reason to credit this explanation. The English, German and French teams have become accustomed to use the poor stuff, and, therefore, have learned to regulate their carburetors accordingly, while this was a new condition to the Americans, as is evidenced by the fact that Winton worked so long with the carburetor on his machine that he was 40 minutes late in starting.

All of the twelve competitors started, three representing each country-England, France, Germany and America. The course, which has been described in a previous issue, was admit- ted to be a pretty bad one, full of bad turns; the fact that accidents befel two of the English competitors, who had the best opportunity to become acquainted with it, proves this. J. W. Stocks, of the English team, was the first to drop out of the race, having smashed the front of his car by running into a stone hedge at one of the turns on the first round. Stocks, fortunately, was not hurt. Jarrott, of the English team, was the second; he ran into the bank near Stradbally, and completely wrecked his car, dislocating his collarbone and almost killing his mechanic.

Mooers, of the American team, had trouble with his transmission gear, caused by a tire coming off the rim, throwing the car into the hedge, and after suffering considerable delay, retired in the second round.

Foxhall Keene, the American who drove one of the German Mercedes cars, made the best time of any on the first round, beating Jenatzy’s time on this stake four minutes; but one of the tires came off his machine and it was then discovered that the rear axle was in bad condition, and although Keene continued for another round, the officials decided it was unsafe for him to continue.

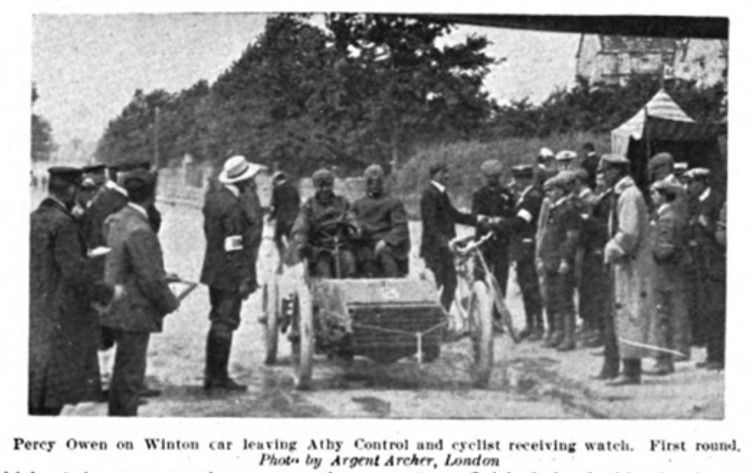

Winton, who was unable to start on time, owing to trouble with his carburettor, due, it is said, to poor gasoline, losing over 40 minutes at the start, made good time for a few rounds, although his engine misfired badly through poor carburation, and when the carburetor again refused to act quit. Owen had trouble with his gasoline line on the second round, causing a long delay, but continued until the race was called off.

De Caters, who had made good time throughout the race and seemed likely to gain second or third place, broke an axle a few miles from the finish.

DESCRIBED BY AN EYE-WITNESS.

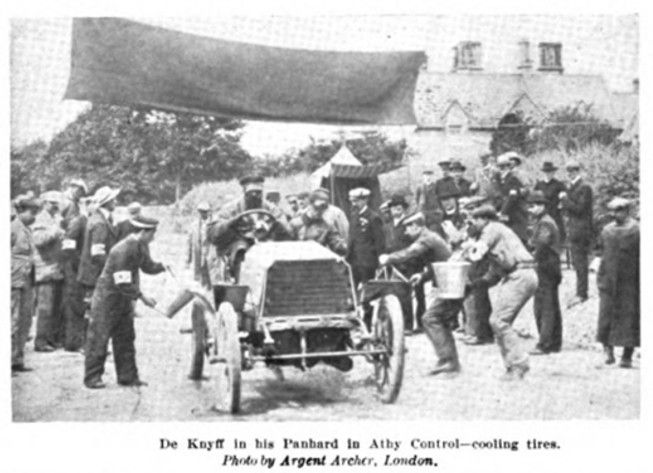

The Automobile Club of Great Britain and Ireland had built a large grand-stand directly over the road near the starting and finishing point, at Ballyshannon, and the morning of the race, the scene at the starting point, which about 100 yards on the lower side of the grandstand, was full of life and bustle hours before the pilot car (which preceded the racers) was dispatched. Well before six the racers had arrived. Numberless cinematograph operators had taken up advantageous positions from which to secure views of the start, whilst the number of general photographers and snapshotters was legion. At 6 sharp all traffic was stopped on the course, and a few moments afterward Foxhall Keene, on his racing Mercedes, drove up with Mrs. Foxhall Keene on board. A little after 6 ominous clouds began to gather on the horizon, throwing into sharp relief the camp near the Ardscull Moat. At 6.30 the first “pilot“ car started on its course round one of the circuits. At 6.36 the second “pilot” started on the other circuit. For a considerable distance on either side of the grandstand the road had been well oiled, all the troubles arising from dust being thereby eliminated. The enclosure was well filled before the start, and a good sprinkling of spectators was on the grand- stand before the first car was sent off. As S. F. Edge, who was appointed to start first, took up his position in his car at four minutes to seven a volley of clapping greeted him which drew general attention to the imminent starting of the great race. At seven to the second Major Lloyd gave the send-off, the firing of the pistol speedily bringing the few who were not already watching the scene intently up to the nearest point of advantage, and with set and determined face the holder of last year’s cup shot under the grand-stand at good speed to work up to a splendid ‚pace before the end of the oiled portion of the course was reached, the car disappearing in a cloud of dust over the extreme point of the rising ground on which the start was made. Then came a wait of seven minutes, which seemed four times as long. A shake-hand from a compatriot and the Chevalier de Knyff on the first Panhard was off. He was not as quick to pick up speed as Edge, but fine traveling was made before he was out of sight.

Owen, on the first American car, then wheeled into place so quietly that its exceptional power of making itself heard by means of its exhaust could hardly be thought possible. The pressure of the photographers and others at this time was keenly felt by the officials, but all round good temper was displayed, and it was a case of give and take. There was a sportsmanlike “God-speed“ from Jarrott, and the next moment Owen had slipped in his clutch, moving slowly away in strong contrast to the previous competitors. The intervals, although in each case the full seven minutes, seemed to grow shorter as each car came up to the lone. It seemed as if No. 3 had hardly got away before the first German Mercedes car was in place. Jenatzy was the driver of No. 4, he receiving a tumultuous send-off from his good-wishers. As with the other competitors, a salvo of applause greeted his departure, which, so far, appeared the best „get-away.”

The excitement in the enclosure and stand ran high by this time, and the crowd pressed forward in the enclosure, endangering the somewhat feeble wire fencing which separated the eager onlookers from the course.

Following the lead of one observant individual, the occupants of the grandstand as each car each car passed under, turned as one man and peered through the spaces left between the planks to watch the disappearing racer over the top of the rise as it seemed to plunge head first into a belt of trees. The sight was a very remarkable one.

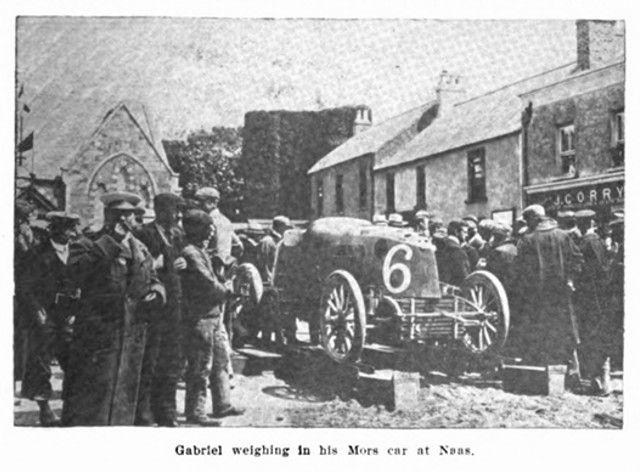

Jarrott was soon settled comfortably and listening to the last warning words of the starter, and with eyes fixed on his straight path, merely to be turned aside momentarily as a crash on his right announced the collapse of a huge branch of a tree which, being loaded beyond reason with human freight, had taken this drastic method of signifying its objection, Jarrott was on his way, with a splendid start. Gabriel, the hero of the Paris-Madrid, then wheeled into place on the Mors car, and at the word „go,“ surrounded by a halo of exhaust, he literally jumped away and seemed to score the quickest start up to that moment. Mooers, on the wire-bonneted Peerless, with a tiny American flag pinned over his heart, was instantly in place ready for his turn. A turn of the starting handle tested the ignition. Then, as the time drew near, another try and stoppage caused a momentary cloud of anxiety to pass over the American’s face. At the word „go,“ with the pushed assistance of his mechanician, he got away poorly. He had forgotten to release the brake. Two or three seconds lapsed before he was fairly under way, and then, greeted with ringing cheers as his engine settled down to work, he moved slowly away. With a last look over the car for a little final adjustment, Baron de Caters, on the eighth car, another Mercedes, was sent on his round-a grand start. By this time 55 minutes had been consumed, and the turn of the last representative of England came. Stocks, the selected driver, was instantly ready. After a rather halting start he made up for loss of time before he reached the top of the rise, and speed was expressed in the bumping of the car as it passed out of sight, the density of dust beyond the oiled portion of the road by this time having considerably abated.

Congratulations from all sides were waiting for Henry Farman, on the second of the Panhards, as his engine, impatient to get to work, fired off volleys of explosions. His official number in the race was 10, but his old Paris-Madrid number, 51, was still faintly visible upon the radiator. Then came a second of keen disappointment as his engine stopped. A rush of help, a fresh turn of the handle, and Farman had disappeared view, almost before the echoes of the encouraging hurrahs had died away. Rumors of something wrong with Winton’s big car caused a sympathetic murmur to pass round the intensely interested onlookers, intensified, as his car, No. 11, was pushed to the side of the starting line, where he, on one side of the car, and his mechanician on the other, set to work with a will to remedy the evil – carburetor troubles. Although Winton declared he could not start, he and his assistant worked on manfully, and a sigh of sympathy was heard from those in the immediate neighborhood of the car who knew the ill-luck with which he had been visited. By then the word was passed for Foxhall Keene to come forward as the last German representative and the last of from the competing cars. He was away – slowly – by 8.17, after a stop and re-start of the engine, losing thereby some 17 or 18 seconds. The starting of the eleven cars altogether occupied 1 hour 17 minutes.

With the disappearance of the last car over the ridge the spectators turned their thoughts to matters of much interest to them, to wit – refreshments. Meanwhile absolute clearance of the course was enforced, and it was hardly grasped by the public that Edge in the first car was already in sight of the long straight stretch, finishing up at the Club Enclosure. At 8.23 Edge simply few past, his front wheels leaving the ground a full half foot at the slightest inequality of the road. Britain’s champion was traveling fast, and it could hardly have been possible for him to hear the ringing cheers which were literally hurled at him as he again disappeared on his round of the Western Circuit, almost, it seemed, before he had been sighted. And still Winton worked on steadily, his engine coughing huskily at each fresh attempt to start it.

„Car in sight, car in sight!“ came a stupendous shout, at 8.33¾ A. M., and De Knyff, on his Panhard, was upon us, and was then gone after Edge, who, however, had already close on four minutes in hand.

And still Winton stood to his guns. An official suggestion that he should change his position from the course to a side road brought from him a reminder that he was „in the race,“ „on the course,“ and „doing time,” and competitors must pass round him as best they might, as he would have to get round them. Well deserved applause followed Winton’s sally, as he had placed his car as near the bank edge as it was possible to force it. Nos. 3 and 4 – Owen’s small Winton and Jenatzy’s Mercedes – passed within 30 yards of each other about a quarter of an hour after De Knyff, the Mercedes drawing further upon the small difference dividing them before the pair disappeared in the distance. This was the most exciting moment in the race. Winton’s new “Bullet“ at last, at 8.58, answered to the persuasion of his owner, and passed away on the first round to the encouragingly vociferous cheers of the masses, who thus gave vent to their admiration of the American’s pluck.

Mooers appeared for the first time from the start at 10.11, having had ill luck at Athy. Jenatzy, eight minutes later, had completed his full circuit in 1 hour 50 minutes 17 seconds net. At the time of the cars passing only the gross times were available, and the very uncertainty as to which of the cars were best on net time, although in a measure it detracted from the enthusiastic interest of the various supporters of each nation, was at the same time compensated for by the lack of general interest which would have resulted from the knowledge that any particular competitor was a long way ahead. Winton, on the larger car, was timed for the eastern circuit at 10.30, which made his gross time 2 hours 20 minutes, allowing for the very late start made by him. Taking, however, the time elapsed from his actual start his speed was not such as to make his competition a serious element in the contest.

Owen, on the other Winton, after covering the western circuit, had got into the same stretch of road with his “stable companion,“ a „bunch” looking likely at Kilcullen Corner when in two minutes Gabriel followed close upon his heels. By this time the fact that Stocks was still missing from his first round of the Eastern Circuit, and that Jarrott had not yet finished the double circuit, gave rise to a feeling of regret that Great Britain had only one good string left to her bow, this feeling was emphasized as at this moment a private wire came through from Stradbally to say Jarrott was knocked out, followed about ten minutes later by a cheer of relief when Baron de Caters stopped his car on his next round to impart the gratifying news that, although Jarrott’s car was smashed up, this popular driver had escaped with only trifling injury. Farman, by 11.8, had finished his complete circuit, and sped away, if anything, more speedily than on his first passing. At 11.25 De Knyff came through, commencing his third circuit, and was followed quickly at 11.34 by Keene, and at 11.37 by Jenatzy driving superbly.

At a few minutes to 12 Edge revived the flagging British hopes by speeding past in magnificent style. If cheers could have given him victory he would have been adjudged the winner forth with by the mighty ovation which was accorded him. Gabriel, on the Mors, although reported to have broken down, was, apparently, traveling well when he was timed at six minutes past 12. Not one of the least interesting features of the race was the big rush which took place toward the edge of the course from the remotest points of the enclosure and fields adjoining the course as the signal was given that a car was sighted. About mid-day a thunderstorm threatened, and the announcement at the same time of luncheon caused a general adjournment to the refreshment tents. An excellent repast put everybody into a more contented state of mind and body, especially as, fortunately, the threatened storm was a false alarm.

Presently, however, the rain started and created an immediate stampede from the grand-stand and enclosure. In the meantime the cars were traveling past at short intervals, the Mercedes, continuing their steady pace, already indicating one of them as a probable winner of the cup. At 1.15 the rain started in earnest for a short space of time, and the surface of the course began very quickly to show the effect. New interest now in the half-over race was immediately apparent, and speculation rife as to the likely effect the sudden change might have upon the various cars remaining in.

By the half hour, Winton, who was still pegging away, passed, Gabriel, Edge, De Caters and Farman following at intervals in the order named. Keene gave up at Kilcullen, after doing three circuits owing to a broken axle. Soon after 2 the sun shone out once more, and mackintoshes and other unsightly wraps disappeared as if by magic, vari-hued sunshades taking their place, the scene once more presenting a brilliant picture of softly-blended colors, only, however, to give place later to a gradually increasing wind which made itself felt particularly on the elevated part of the grand-stand and threatened destruction to the timekeeper’s tent.

At 3 o’clock Gabriel finished his fifth circuit. Winton, at 4 minutes past the hour, finishing his third. The drivers still remaining in, steadily persevered with their self-imposed labors, and, watching the bumping and erratic movements of the vehicles as they flew past, one and all marveled that machinery could hang together under such stress. But the admiration for the men who were able to stand the awful strain of driving the cars for ten or eleven hours on end, relieved only by the short intervals of rest afforded by the controls, was expressed by silent wonder for want of words to convey an adequate appreciation of their endurance.

De Caters, at 3.13, passed, followed soon after by Farman, Edge completing his fifth circuit at 3.34. Owen at 3.42 finished his third circuit, and at 3.57 De Knyff started his last and seventh lap, sending his machine along as if he had only just commenced. Jenatzy completed his sixth lap at two minutes past 4, and was the second man to start on the last round. Starting with about nine minutes to the good, bar accidents, he looked like lifting the cup. The other last laps were timed away-Gabriel at 4.43, De Caters, 4.51, with Farman a minute after close on his heels, both simply flying over the road, and Edge at 6 o’clock. Owen was again seen at 5.3212, with De Knyff only half a minute behind him finishing his seventh and last round.

The cheers had barely died away before the winner of the cup, Jenatzy, was sighted in the distance, he passing the winning post at 5.36. The first to congratulate him was Mr. Gray Dinsmore, the owner of the car and the representative of America on the International Cup Commission. At 5.49 Winton again passed, followed ten minutes afterward by Edge completing his sixth round, Gabriel starting his last lap at 6.20. Farman at 6.30 finished his race, and six minutes past 7, with Owen not signaled, the International Commission determined to declare the race over.

The electrical timing system for the flying mile ending at the club enclosure, besides being of considerable interest, served a double purpose by giving due notice of the approach of another car when a mile off and preparing everybody to be ready for its reception.

The course was adequately guarded and the arrangements throughout were as nearly perfect as could be.

Not a personal accident was recorded beyond the one in which Mr. Jarrott was the sufferer. Between three thousand and four thousand policemen watched the course, to insure that it be kept absolutely clear.

Ten miles of electric cable had been laid down underground to connect Ballyshannon with Dublin.

Picture captions.

M. Jenatzy, the winner, in his Mercedes car before the race. Photo by W. Lawrence, Dublin.

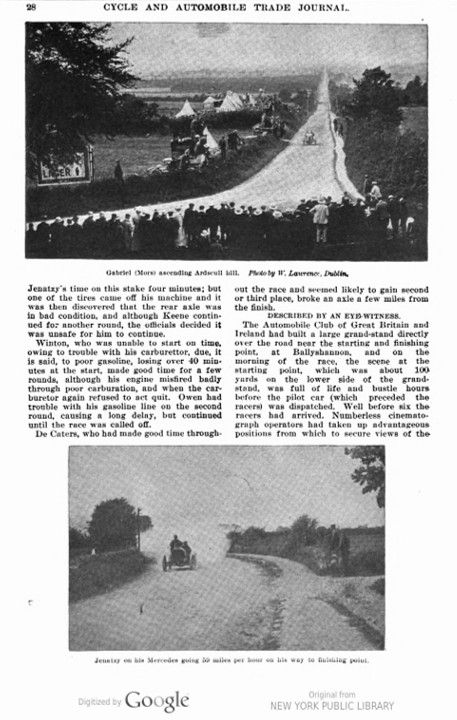

Gabriel ascending Ardscull Hill. Photo by W. Lawrence, Dublin. – Jenatzy on his Mercedes going 59 miles per hour on his way to finishing point.

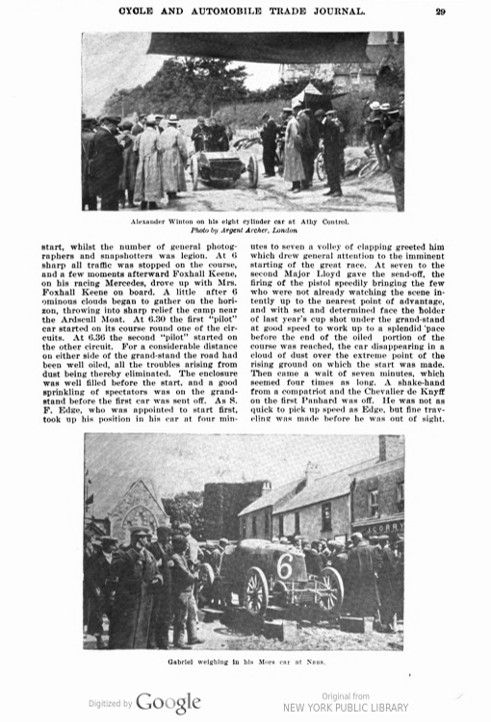

Alexander Winton on his eight cylinder car at Athy control. Photo by W. Lawrence, Dublin. – Gabriel weighing his Mors car at Naas.

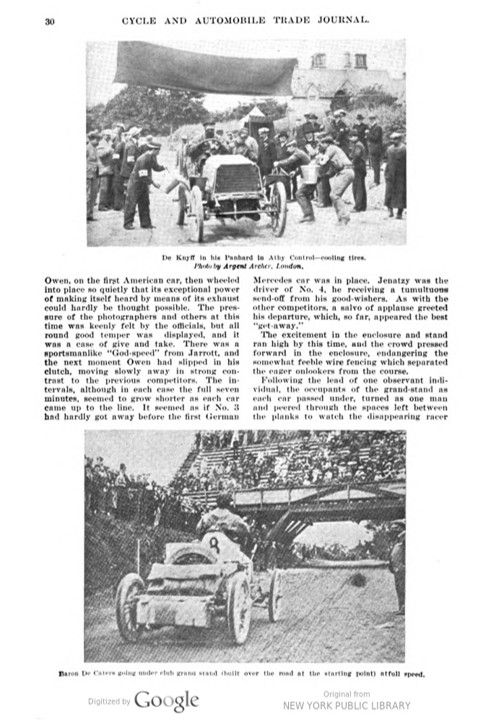

De Knyff in his Panhard in Athy Control – cooling tyres. Photo by W. Lawrence, Dublin.

Baron de Caters going under club grand stand (built over the road at the starting point) at full speed.

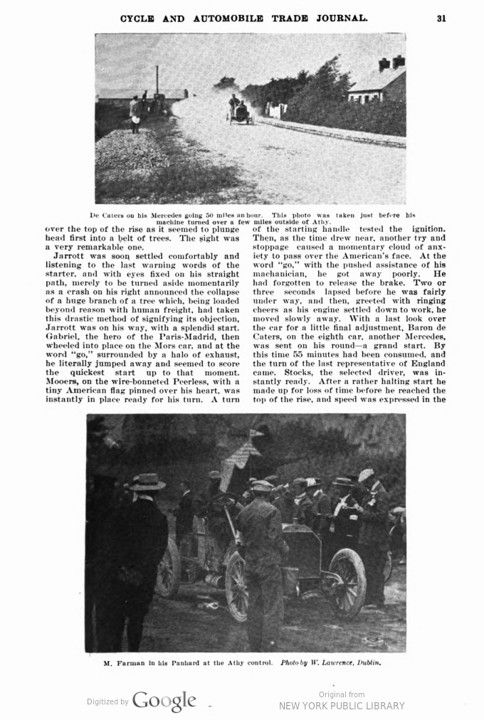

De Caters on his Mercedes going 50 miles an hour. This photo was taken just before his machine turned over a few miles outside of Athy.

M. farman in his Panhard at the Athy control. Photo by W. Lawrence, Dublin.

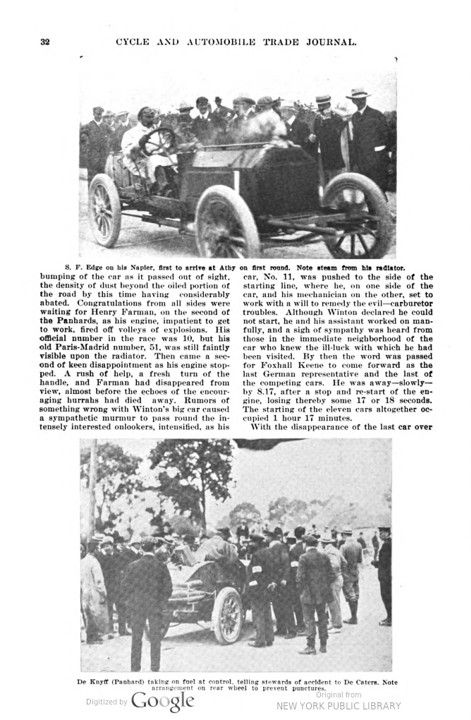

S.F. Edge on his Napier, first to arrive on first round. Note steam from his radiator.

De Knyff (Panhard) taking fuel at control, telling stewards of accident to De Caters. Note arrangement on rear wheel to prevent punctures.

Foxhall Keene on Mercedes at Kildare Control. Photo by W. Lawrence, Dublin.

Percy Owen on Winton car leaving Athy Control and cyclist receiving watch. Photo by W. Lawrence, Dublin.

Charles Jarrott in his Napier cat at Athy Control. Photo by W. Lawrence, Dublin.

Mooers and his Peerless car at Athy after his accident. Photo by W. Lawrence, Dublin. – J.W. Stocks in his Napier car before the race Photo by W. Lawrence, Dublin.