TText and jpegs by courtesy of hathitrust.org www.hathitrust.org, compiled by motorracinghistory.com

MOTOR AGE Vol. XXV, No. 23 Chicago, June 4, 1914

The 500-Mile Race as Seen from the Repair Pits

Seven Leaders Did Not Lift Hood During Event-Troubles of the Cars

By Darwin S. Hatch

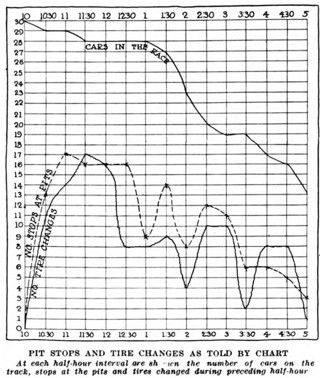

INDIANAPOLIS, Ind., May 30 – It is at the pits that a great race is won or lost. The story of the tortoise and the hare is re-enacted a dozen times at every speedway race. Today’s 500-mile event was no exception to the rule. It was not by amazing speeds alone that those cars and drivers which were crowned speed kings after the finish of today’s 500-mile grind won their laurels. It was as much by virtue of the stamina and freedom from mechanical difficulties of the cars which permitted them to keep on running lap after lap without making frequent stops at the pits.

There is a lesson in the fact that the first seven cars to cross the finish line never lifted the hood during the race and that all the others that tardily completed the 500-miles had been held up by the need of some mechanical adjustment or replacement.

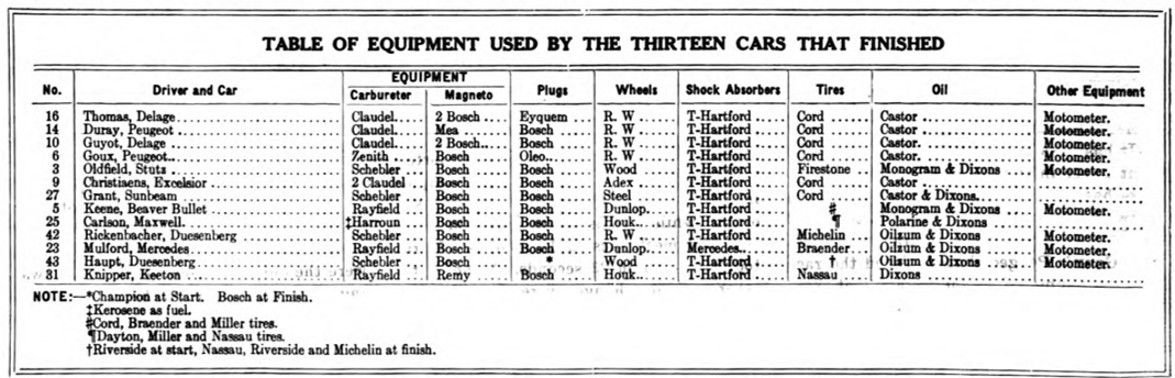

Delage Boast Is Proven

It has been the boast of the Delage team that never in the racing history of Delage cars has a hood been lifted or a tool used between start and finish, nor was this good record changed today. Duray’s Peugeot and Goux’s Peugeot both finished the race without unbuckling the strap that held down the bonnet. Not a tool touched the tiny Peugeot and Goux’s car was submitted to this indignity but once, when it was necessary to put a new bolt in a front spring hanger. Oldfield’s Stutz shares in the honor of the foreign cars and is the only American car to finish which does share in the honor of not having been touched except for tires and supplies. Christiaens‘ Excelsior and Harry Grant’s Sunbeam also came through with a clean score so far as mechanical work on the car is concerned.

Speedy Tire Changes

Pit work in general was not particularly fast, although where tires and fuel supplies caused the stop, great speed was shown. When mechanical difficulties was the cause of the stop the work was done with more deliberateness. The Stutz team holds the record for fast tire changes. The Stutz pitmen changed a tire and filled gasoline and oil tanks in a record time of 25 seconds on Anderson’s machine. Burman and Carlson divide honors for the shortest stop at the pits, Burman relieving Knipper in the Keeton with a halt of only 17 seconds, while Carlson in the Maxwell switched mechanics in 18 seconds. Duray took on water in 23 seconds. Some of the other fast tire changes were the following: Goux, 30 seconds; Keene, 42 seconds; Thomas, 50 seconds; Carlson, 55 seconds; Rickenbacher filled his oil tank and changed a tire in 37 seconds. Harry Grant’s pit work was noticeably slow. At one time it took 3 minutes and 30 seconds to change a tire. Grant, by the way, had demountable steel wheels and luckily did not have to change but six tires.

Prize for Fast Work

Work at the pits was more interesting than usual this year on account of the com- petition for the Waltham efficiency trophy, which was put up for the car, among the first three to finish, that spent the least time at the pits. Thomas‘ Delage won this prize as well as most of the others. He made but three halts at the pits, the time consumed totaling only 4 minutes 55 seconds.

The Peugeot driven by Duray, which won second, also was the runner up for the Waltham efficiency prize. The tiny Peugeot made only three stops at the pits and was held up for a total time of 5 minutes and 27 seconds. Guyot’s Delage halted only twice, but as one of the stops was for over 8 minutes it brought the total time out up to 9 minutes 15 seconds. As these were the three first cars to finish, they were the only ones considered in the awarding of the efficiency trophy.

Barney Oldfield’s Stutz made the best record of any of the cars to finish. Oldfield stopped only three times and lost only 3 minutes 36 seconds. Christiaen’s Excelsior halted only twice at the pits but lost 6 minutes 17 seconds in doing so, as he was running in sixth, seventh and eighth places throughout the race, with Grant close at his heels, the time lost was quite valuable to the Belgian.

Tires Cause Most Stops

By far the greatest number of pitstops among those to finish were due to blown- out tires. Thomas changed five tires during the race. Duray in the little Peugeot changed an equal number. Guyot’s Delage was a little more lucky, wearing out only two casings during the entire 500 miles. Oldfield changed but three during the five centuries and made those changes in what is considered record time. Christiaens changed four of his casings in the two stops he made. His pitwork was slower than that of most of the contenders.

Thomas ran 140 miles before he made his first stop; then he rolled into the pits and changed both rear tires, being held 12 minutes. An hour later, after he had run 215 miles, he came in and changed a left rear, getting away in 50 seconds. His last stop during the race was at the end of the 350th mile, when he stopped for fresh supply of gasoline water and oil, taking the opportunity at the same time to change both right tires. This held him 2 minutes 25 seconds at the pits. He ran the remainng 150 miles without a halt. He holds that it will be impossible to make any better speed for some time on account of tires.

Duray did not find it necessary to stop until he had run 170 miles. After these two hours of continuous circling of the brick oval he halted to change the right rear and the right front tire and also fill up the gasoline tank. This caused a delay of 2 minutes 6 seconds. An hour later he stopped for water but was away again in 23 seconds. Another two hours and he came in for the last time for gasoline and oil. At the same time he changed both rear tires and the front one. Duray did not rely on speed so much, although he had it to spare, as he did on freedom from lost time at the pits.

190 Miles Without a Stop

The first of Guyot’s stops came at 2 hours and 16 minutes after the start, during which time he had covered 190 miles. He changed two tires and filled up his gasoline and oil tanks. The motor was hard to start, and quite a little time was lost in getting under way after he was ready to go. Eight minutes 20 seconds elapsed be- fore he was on the track again. After completing his 376th mile, Guyot halted for 55 seconds to take on gasoline. The remaining 125 miles of the race were completed without a halt.

Goux Had Much Tire Trouble

Goux’s Peugeot had a great deal of tire trouble. The Frenchman made ten stops in all, and all but one of them were occasioned by tire changes. He put on eleven new tires during the 500 miles. His first tire trouble occurred only 11 minutes after the start, when he had to change the right front wheel but got away in 44 seconds. Twenty minutes later he was in again, rolling down to the pits with the cords from the tread wrapped around the brake band. He changed both rear tires this time and was stopped for 1 minute 31 seconds. After this, he ran a full hour without difficulties but then came in for replacement on the right rear wheel. He filled up his gasoline tank at the same time, using up 2 precious minutes. Twenty minutes later the new tire blew out and he made the change this time in 29 seconds. This tire lasted 40 minutes, then it had to be changed, occasioning a stop of 1 minute. Thirty-eight minutes later he was in again. This time, also, he changed the right rear tire. He took occasion to refill his gasoline tank during this stop.

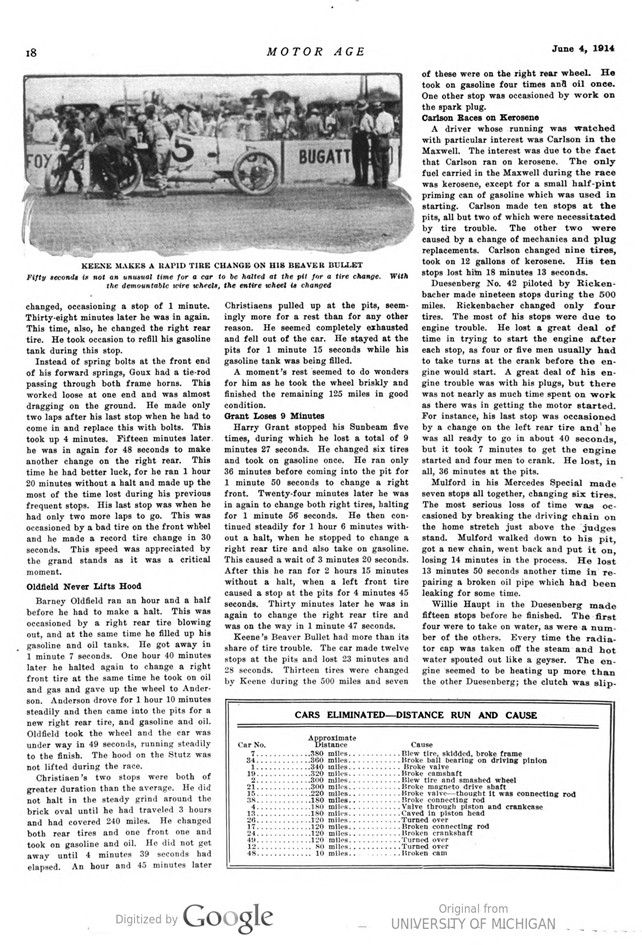

Instead of spring bolts at the front end of his forward springs, Goux had a tie-rod passing through both frame horns. This worked loose at one end and was almost dragging on the ground. He made only two laps after his last stop when he had to come in and replace this with bolts. This took up 4 minutes. Fifteen minutes later he was in again for 48 seconds to make another change on the right rear. This time he had better luck, for he ran 1 hour 20 minutes without a halt and made up the most of the time lost during his previous frequent stops. His last stop was when he had only two more laps to go. This was occasioned by a bad tire on the front wheel and he made a record tire change in 30 seconds. This speed was appreciated by the grand stands as it was a critical moment.

Oldfield Never Lifts Hood

Barney Oldfield ran an hour and a half before he had to make a halt. This was occasioned by a right rear tire blowing out, and at the same time he filled up his gasoline and oil tanks. He got away in 1 minute 7 seconds. One hour 40 minutes later he halted again to change a right front tire at the same time he took on oil and gas and gave up the wheel to Anderson. Anderson drove for 1 hour 10 minutes steadily and then came into the pits for a new right rear tire, and gasoline and oil. Oldfield took the wheel and the car was under way in 49 seconds, running steadily to the finish. The hood on the Stutz was not lifted during the race.

Christiaen’s two stops were greater duration than the average. He did not halt in the steady grind around the brick oval until he had traveled 3 hours and had covered 240 miles. He changed both rear tires and one front one and took on gasoline and oil. He did not get away until 4 minutes 39 seconds had elapsed. An hour and 45 minutes later Christiaens pulled up at the pits, seemingly more for a rest than for any other reason. He seemed completely exhausted and fell out of the car. He stayed at the pits for 1 minute 15 seconds while his gasoline tank was being filled. A moment’s rest seemed to do wonders for him as he took the wheel briskly and finished the remaining 125 miles in good condition.

Grant Loses 9 Minutes

Harry Grant stopped his Sunbeam five times, during which he lost a total of 9 minutes 27 seconds. He changed six tires and took on gasoline once. He ran only 36 minutes before coming into the pit for 1 minute 50 seconds to change a right front. Twenty-four minutes later he was in again to change both right tires, halting for 1 minute 56 seconds. He then continued steadily for 1 hour 6 minutes without a halt, when he stopped to change a right rear tire and also take on gasoline. This caused a wait of 3 minutes 20 seconds. After this he ran for 2 hours 15 minutes without a halt, when a left front tire caused a stop at the pits for 4 minutes 45 seconds. Thirty minutes later he was in again to change the right rear tire and was on the way in 1 minute 47 seconds.

Keene’s Beaver Bullet had more than its share of tire trouble. The car made twelve stops at the pits and lost 23 minutes and 28 seconds. Thirteen tires were changed by Keene during the 500 miles and seven of these were on the right rear wheel. He took on gasoline four times and oil once. One other stop was occasioned by work on the spark plug.

Carlson Races on Kerosene

A driver whose running was watched with particular interest was Carlson in the Maxwell. The interest was due to the fact that Carlson ran on kerosene. The only fuel carried in the Maxwell during the race was kerosene, except for a small half-pint priming can of gasoline which was used in starting. Carlson made ten stops at the pits, all but two of which were necessitated by tire trouble. The other two were caused by a change of mechanics and plug replacements. Carlson changed nine tires, took on 12 gallons of kerosene. His ten stops lost him 18 minutes 13 seconds.

Duesenberg No. 42 piloted by Rickenbacher made nineteen stops during the 500 miles. Rickenbacher changed only four tires. The most of his stops were due to engine trouble. He lost a great deal of time in trying to start the engine after each stop, as four or five men usually had to take turns at the crank before the engine would start. A great deal of his engine trouble was with his plugs, but there was not nearly as much time spent on work as there was in getting the motor started. For instance, his last stop was occasioned by a change on the left rear tire and he was all ready to go in about 40 seconds, but it took 7 minutes to get the engine started and four men to crank. He lost, in all, 36 minutes at the pits.

Mulford in his Mercedes Special made seven stops all together, changing six tires. The most serious loss of time was occasioned by breaking the driving chain on the home stretch just above the judges stand. Mulford walked down to his pit, got a new chain, went back and put it on, losing 14 minutes in the process. He lost 13 minutes 50 seconds another time in repairing a broken oil pipe which had been leaking for some time.

Willie Haupt in the Duesenberg made fifteen stops before he finished. The first four were to take on water, as were a number of the others. Every time the radiator cap was taken off the steam and hot water spouted out like a geyser. The engine seemed to be heating up more than the other Duesenberg; the clutch was slip- ping; the pump was not working properly. Five different times new spark plugs were put in the motor. It seemed that the high compression caused them to break. Nine tires were changed during the race. The clutch was not disengaged on stopping – seemingly it had been wedged to prevent slipping-and the rear wheels were jacked up on starting. When the engine got going at a good speed, the car was pushed off the jacks and started out on high.

Knipper’s Keeton, which was the last car to finish, made thirteen pit stops, changing seven tires. Burman took the wheel of the Keeton after his car had been eliminated and drove for a while, giving place to Knipper and again taking the driver’s seat near the finish. Valve trouble occasioned a considerable loss of time near the end of the race. Knipper and Burman, took it to be ignition trouble and put in a new coil, later finding a stuck valve was the trouble. The car had a very complicated spark control connection which ran from one side of the engine around the front to the magneto on the other side. Some of these connections loosened up and this caused trouble for a time. „Mercedes Fritz,“ Knipper’s mechanic got after it with his Speednut wrench which he carried throughout the race and is very proud of the speed with which the repair was made. He also distinguished himself by slop- ping water all over the magneto when filling the radiator, causing a failure to start until the two distributers had been wiped out.

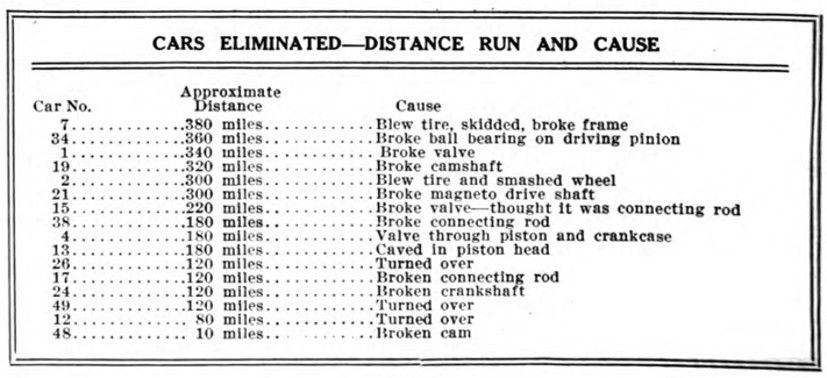

Those Who Fell by the Wayside

Of the cars eliminated from one cause or another during the race, Boillot’s Peugeot ran the longest and was in third place and gaining rapidly when the accident occurred which put it out. Boillot was leading at 360 miles, but a tire change let Thomas and Duray pass him.

A Vindictive Casing

It was while traveling at very high speed in the effort to regain the lost leadership that he blew another tire on a turn. The tire flew up and hit him on the arm, causing him to lose control of the car for a moment. Not satisfied with this, the casing again struck him, this time on the head. The sharp twist that the plucky driver gave the steering wheel caused such a quick change in direction at this high speed that a side frame member was cracked, putting Boillot out of the race.

During more than 370 miles in which Boillot was a contender he made five stops at the pit, all but one of which were for tires. He changed five tires and his pit men made rapid time in the changes, 40 seconds for one tire and 1 minute 2 seconds for two can be considered pretty fast work. During one of the stops for tires he took on 10 gallons of gasoline and at another time took on 15 gallons more.

Is Unlucky

The Bugatti, which had been expected to make quite a showing for consistent running, was quite unfortunate. Before this car was eliminated after running almost 360 miles it had made fourteen stops at the pits, or one every 23 miles on the average. Tire trouble was the jinx that followed the German. Freiderich changed fourteen tires, getting average of less than 25 miles to a tire. Most of these were on the right rear wheel, as most usually is the case at the speedway.

In addition to the tire trouble the Bugatti had a little difficulty in its oiling system, and stopped once for work on that. In all, this car lost 34 minutes and 34 seconds at the pits. It finally was definitely put out of the race when one of the ball bearings of the driving pinion gave way. At this time the Bugatti was running in thirteenth place and losing ground steadily.

Louis Disbrow’s new Burman car completed almost 340 miles before it was put out of the running with a broken connecting rod. During the time it was in the race it made only four stops and changed only one tire. Nevertheless nearly 54 minutes were lost at the pits, most of which was due to trouble with Burman’s new valve-operating mechanism. This car, like its mate, had just been completed in time for a week’s practice and the valve operating design was a new and untried one, consequently a certain amount of tinkering was necessary. Valves, springs, and cotter pins were changed and spark plugs were renewed. Disbrow was in sixteenth place when eliminated.

Wishart made only three stops before he pulled up to the pits and announced he was out of the running, with a broken camshaft gear. He had put almost 320 miles behind him and looked like a winner. He was in first place at 280 miles and was running in second place when he went out. He changed only three tires and was detained at the pits for a total period of just over 3 minutes.

Cooper Changes Two Tires

Cooper’s Stutz No. 2 accomplished nearly 300 miles of the necessary 500 before a tire blew out, throwing the car into the soft ground of the infield and smashing the wheel. Cooper was not driving at the time, but neither his relief nor the mechanic were injured. Cooper stopped only twice within the run, both times for tires, and changed only two tires. He lost only 2 minutes and 10 seconds altogether making tire changes and taking on oil in 1 minute. Cooper was in fifth place at his finish.

Caley Bragg in the Mercer 21 also covered nearly 300 miles before being eliminated with a broken magneto drive shaft. Bragg made only three stops and changed only one tire, but lost 62 minutes altogether on account of repairs to his oil tank, which had sprung a leak and was losing oil at a great rate. Bragg attempted temporary repairs with a can of shellac, but that did not seem particularly successful. He was running in seventh place when eliminated.

Case of Bad Judgment

Klien’s King had covered nearly 220 miles when it was withdrawn. It is generally thought that Klien’s withdrawal was unnecessary, for when the engine commenced to go bad the driver diagnosed the difficulty as a broken camshaft. Later it was discovered that it was simply a broken valve, which would have meant only a delay of a few minutes while a new one was installed. Klein stopped only twice, the first time for 30 seconds when he took on water, and the second time for 12 minutes while the tire was changed.

Braender’s Bulldog, piloted by Chandler, ran its entire distance of almost 180 miles with but one stop before it was eliminated by a broken connecting rod. This stop was occasioned by a change of spark plug and held Chandler less than 2 minutes. Chandler did not change a tire during the 180 miles. He rode on Braender tires, the same make those with which Mulford last year finished the 500 miles without a change.

Wilcox’s Gray Fox completed almost the same distance as the Bulldog before it was eliminated. Wilcox’s withdrawal caused by a valve dropping into the cylinder and going through both the piston and the crankcase. He only made one stop and that was to replace the broken push rod. Wilcox, likewise, did not change a tire. His tires were Silvertown cords.

Mason, driving his namesake, was eliminated at about 175 miles with a caved-in piston head. He made four stops at the pits, losing 4 minutes and 46 seconds and changing two tires.

Joe Dawson, in the Marmon, had run only 120 miles without a stop of any sort when his accident put him out of the running. He was in seventh place at the time. Burman, in his own car, No. 17, made only one stop before he was eliminated after having run nearly 120 miles. His halt at the pits of 4 minutes and 50 seconds was to change four spark plugs. He changed no tires. His withdrawal from the race was occasioned by a broken crankshaft.

Anderson’s Stutz was eliminated on account of a broken crankshaft after it ran almost 120 miles. Anderson’s one stop at the pits, at which time he took on gasoline and oil and changed a tire, held him only 25 seconds, which is the record for fast pit work.

Gilhooly stopped only once and that time he was flagged down by Assistant Starter DeLong for a warning as to his method of driving. This detained him 3 minutes. A few minutes later his Isotta turned over and was the cause of Daw- son’s accident. The Isotta had gone a little over 100 miles.

Chassagne’s Sunbeam never stopped from the time it started until the upset after having gone just under 80 miles. The Ray had negotiated under 10 miles when it went out with a broken cam.